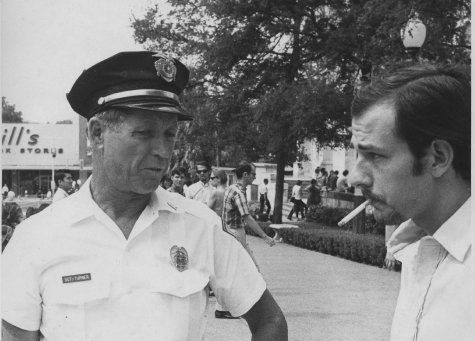

Thorne Dreyer (right) and University of Texas campus cop, October 1966. Photograph Source: Thorne Webb Dreyer – CC BY-SA 3.0

Have you noticed? Sixties folk—organizers, activists, pacifists, feminists and liberationists of all stripes— can’t seem to get enough of the era when they made history. For some it never really ended, though recent history has not been kind to the Sixties. In the 1980s conservatives co-opted the buzz words of the Sixties and touted “The Reagan Revolution.” These days, Trumpers have also scooped up and recycled the vocabulary of that era of protest. They have promoted “Liberation Day” and the arrival of tariffs meant to “make America Wealthy again.” The word underground, which the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky popularized in the title of his best known novella, Notes from Underground, lost much of its bite when a website with information about the weather called itself “The Weather Underground.”

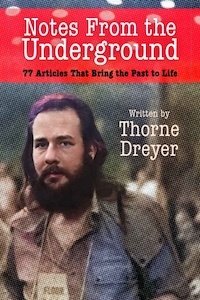

The language and the vocabulary of the Sixties isn’t what it used to be. In some cases the meanings of words have turned into their opposite. Thorne Dreyer, the founder of The Rag and the host of Rag Radio, calls his new collection of 77 articles, “Notes from Underground” and means to honor the past.

It’s true that Dreyer didn’t break any big stories from The Sixties. He didn’t do what Seymour Hersh did for the New Yorker, or what Woodward and Bernstein did for The Washington Post. He didn’t have the resources of the mighty media. But he had his feet on the ground. He saw the action as it unfolded up-close and personal, and perhaps that’s as valuable as the headline news from the White House, the Pentagon, Watergate or Woodstock.

Dreyer didn’t write about the murder of Fred Hampton but he wrote about the murder by the police of Houston’s African American activist, Carl Hampton. And no matter that he used some of the overheated language of the day and wrote that “Hampton was picked out for extermination” and that “the Houston police ripped off one of the most dedicated and selfless revolutionaries in the city. Dreyer poured his heartfelt politics into prose.

Some of the pieces appeared in Austin’s signature underground paper and others in the Houston Chronicle and the Texas Observer, “sea level publications,” as they were called. Underground reporters and editors like Dreyer sometimes migrated from media down under the surface to media up above. The gap between the two doesn’t seem as wide as it once did. As someone famous once observed, “yesterday’s heresy is tomorrow’s orthodoxy.”

In a 1976 article published in the Texas Monthly, Dreyer asked if the Sixties generation made “any difference?” And whether it left “its mark on the world?” His answer, “Who knows?” He adds “I have no intention here of constructing some grandiose analytical overview of the Sixties explosion.” Fair enough. He wasn’t then and isn’t now a theorist. In that 1976 piece, Dreyer goes on to offer sketches of some of his friends who were movement organizers and who were “white, thirtyish and come from moderately affluent family backgrounds.” That sounds like Dreyer himself. He adds that the folks he profiles are like him “mostly native Texans.” He ends the piece with a quotation from Stoney Burns, a Texas writer and hippie who ran for Dallas County sheriff in 1972 and who says it was an “exciting time” and that “I sure had fun.”

Half-a-century after Dreyer first asked his relevant question about the Sixties generation, it’s still worth asking whether it made its mark on history. In my view it did and it didn’t. It helped to end the War in Vietnam, undo the wrongs of legal racial segregation, altered white middle class lifestyles in the cauldron of the counterculture and freed women from some of the chains of the patriarchy.

But now in the age of Trump and with a counter revolution in full force many of the achievements of the Sixties generation seem to have been undone or faded into a sea of reaction the likes of which has not been seen since the era of Jim Crow when the achievements of Reconstruction were undone by white supremacists, racists, bigots and members of the KKK.

Some of my friends who were activists in the Sixties tell me they don’t know what to do now to counteract Trump and his cronies. In my recollection they weren’t all that savvy in the Sixties, but were often carried along helter-skelter by the current of contemporary events. Where, one wonders, was Dreyer in the Sixties? An article he wrote in 1969 with Victoria Smith which was originally published in Liberation News Service and is contained in Notes from the Underground provides some answers.

“We cannot individually remold our lives,” he and Smith wrote. “No matter how beautiful the vibrations you emanated, you couldn’t create the good society in the entrails of the decaying body.” No mention is made of the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW), the radical labor union, whose members argued that it was essential to “build a new world from the shell of the old.”

Feminist Gloria Steinem recycled the IWW notion not long ago and called for “a revolution from within” which gained traction in feminist circles and among Sixties radicals who turned to meditation, Buddhism and spirituality. Dreyer and Smith, argued in their 1969 article that a “new kind of left has emerged in America that combines the positive and the negative, the vision of a better way and the need to destroy the old, the loving and the burning.” Depending on where you stood on the spectrum and whether you trashed or sat-in nonviolently you emphasized either the loving or the burning.

The authors denounce “chickenshit liberalism,” the sectarian cliquishness of the Old Left and hail the arrival of the underground press as a “revolutionary departure from the traditions of American journalism. They allow that “radical journalists came and went“ and suggest that “their work never approached the stylistic or contextual impact that today’s Movement press is having.” That remark and others similar to it might remind readers that Sixties radicals sometimes rejected radical history and the achievements of the past, including benchmark publications like The Masses and The New Masses.

Notes from the Underground is divided into seven parts; “Years of Protest and Upheaval,” “Night Riders and the New Politics,” “Echoes of the Resistance,” which includes articles from the 21st century”; “Special Reporting” with news of Houston ; and “Progressive Voices” which offers interviews with folk singer Judy Collins, SDSer Carl Davidson, Yippies Judy Gumbo and Nancy Kurshan, Weather Undergrounders and more, Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, and Bernie Sanders often a lone voice in the wilderness of American politics today. No one I know has done more to transcend the sectarianism of the old New Left than Dreyer.

In the last section of his book, “Remembrances,” he offers profiles of folks little known outside of Texas such as Stoney Burns, Jack A. Smith, Daniel Jay Schacht and Thorne’s accomplished artist mother Maggie. Here, as elsewhere he honors Texas radicals and radicalism often neglected by underground newspapers on both coasts.

Dreyer has always rightly insisted that Austin ought to be included in accounts of the Sixties, and not be forgotten in the barrage of stories about New York, Madison and Berkeley. Parts I and II bring the past to life and thereby achieve the author’s stated goals. “Echoes of the Resistance” feels less timely, and the profiles at the end don’t significantly enhance the portrait of the era of protest and upheaval.

Dreyer backs away from the language of the Sixties and refrains from calling it a revolutionary period. He uses words like “progressive,” “protest” and “upheaval.” When asked why he unearthed, collected and published the articles in Notes, Dreyer said be wanted to write a memoir, a history of the movement from the perspective of a personally-involved writer, “a journalist/participant,” and to “fill in a gap of knowledge about the out-sized role that Austin and Houston played in the story of the Sixties.”He has done that,

It has often been said that a picture is worth 1,000 words and that’s true of some of the pictures in this volume that depict a protester surrounded by marines, young men at a headshop talking about “police harassment” —a constant threat— and the reproduction of a stunning front page of the Rag from 1972 that offers an iconic image by artist Jim Franklin of an armadillo about to cross what looks like an endless highway littered with broken automobile tires.

The post Liberation and Cooptation, Repression and Resistance: Reflections on the Sixties appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.