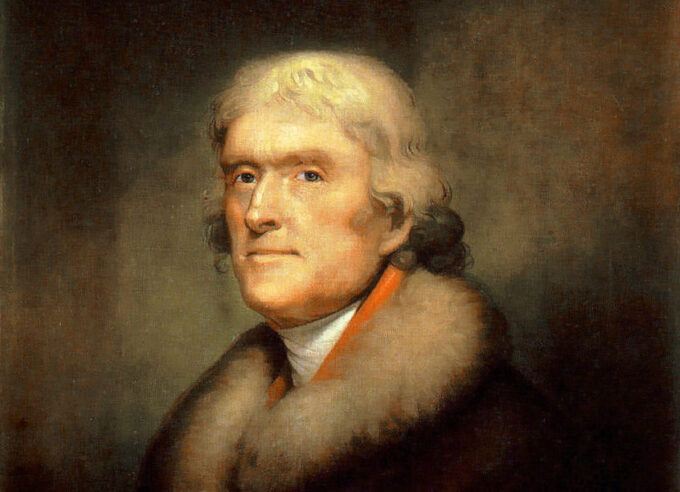

Thomas Jefferson, an 1805 portrait by Rembrandt Peale – Public Domain

“When in the Course of human events…” You remember those resounding words which are as memorable as “We the People…” The brothers who signed the USA’s founding document might have called it a “Manifesto.” After all, like many manifestos it expresses a political agenda. Instead, they called it “a Declaration,” and indeed they declared in about 1,300 words, most of them like “rights, “laws” and “Facts,” part of everyday conversations, and some high falutin words like “perfidy” and magnanimity.”

Thomas Jefferson, a Virginian, a slave-owner and a wordsmith, drafted the Declaration of Independence apparently in isolation in a rented room in Philadelphia in June 1776. The Second Continental Congress adopted it on July Fourth which is why many of us on that day watch parades, wave the Stars and Stripes and feast on barbecue. Some citizens may even recall the Declaration of Independence.

Seven residents of the senior community where I live in San Francisco have been rehearsing for our performance of the Declaration. Several residents have observed how much it resonates today with the antics, the crimes and misdemeanors of the Trump administration. The founding brothers are turning in their graves. They’re surely applauding the “No King” demonstrations that have swept across the nation.

Ever since 1776, Americans have been declaring their independence from someone and or something, including the US itself. Huck Finn declares jhis independence at the end of the book in which he floats down the Mississippi with Jim and who aims to “light out for the territory.” The Confederacy declared its independence from the Union in 1861, determined to preserve forever the “peculiar institution” of slavery, which is not once by word mentioned in the US Declaration of Independence, nor is the word “revolution.”

The American revolutionaries didn’t draw undue attention to their revolutionary stance and didn’t identify as firebrands. They were cautious and reasonable as when they explained that they knew that “Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes,” and that “mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.”

The document that Jefferson wrote— and that was signed by 55 other co-conspirators white men of property (including John Hancock, Samuel Adams and Benjamin Franklin) who “pledged to each other our Lives, Our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor”— was very much of its time and place. Indeed, it reflects the ideals of the Enlightenment that emphasized liberty, reason and progress and the political imperatives of what has come to be known as “The Age of Revolution” which began about 1775 and ran until 1848, known as “The Year of Revolution.”

In his initial draft of the document Jefferson had included a passage that condemned slavery and blamed the king for its existence. Delegates from Georgia and South Carolina twisted arms and the passage was deleted.

The “Age of Revolution” kicked off on one side of the Atlantic and spread to the other side and witnessed popular insurrections from the Thirteen Colonies in North America to Europe and then to Haiti and back to Europe. Revolutionaries such as Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense and the American Crisis—an attack on King George III— bounded from England to America and France, where he was arrested, imprisoned and nearly executed.

The ideas contained in the U.S. Declaration of Independence have echoed around the world. It’s not at all surprising that Ho Chi Minh, the Vietnamese nationalist and communist, who spent time in New York before the start of World War I, read the document and that it and the Declaration of the French Revolution inspired him when he wrote The Vietnamese Declaration of Independence.

Unlike Jefferson he was not alone or in isolation when he drafted the document. He was surrounded by like minded Vietnamese patriots.

Of course, Ho stripped the American Declaration of Independence of its racism—the document denounces “the merciless Indian savages” who are said to mean to destroy “all ages, sexes and conditions.” (The American Revolution may have been beneficial for Virginia planters, New York bankers and New England merchants but it wasn’t beneficial for Native Americans.)

After the revolution, the new nation waged a genocidal war against the Indians that lasted centuries and that moved from bloody battlefields on near the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific Ocean.

Ho reminded the Vietnamese and the citizens of the world that “all men are created equal” and “must always remain free and have equal rights,” but that the French imperialists, abusing the standard of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity have violated our fatherland and oppressed our father citizens.”

The Vietnamese Declaration of Independence reads as though Ho had memorized the American Declaration of Independence. He may also have had direct help from Americans in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) who attended meetings chaired by Ho that took place in August 1945.

OSS officer Archimedes Patti a lieutenant colonel in the US Army, claimed that he heard Ho read the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence before he delivered it at a public event in Hanoi on September 2, 1945 when he also announced the birth of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as an independent nation.

Ho’s words would have sounded familiar to Patti, to other Americans in the OSS and to American patriots in Vietnam and the U.S. Indeed, Ho repeated word-for-word the first sentence in the document that Jefferson authored and that Timothy Matlack, a Pennsylvania beer maker, rendered in his own inimitable script.

Ho read: “All men are created equal; they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” He added “This immortal statement was made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776.” Ho felt the need to simplify and to use the word “peoples” in place of “men.” He also targeted a system – imperialism— not a man or a group of men but rather the whole French nation and the “Japanese fascists” who occupied Vietnam during WWII and battled the allies.

Ho explained to his audience that in a “broader sense, this means: All the peoples on the earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free.” Not just to pursue happiness, as Jefferson suggested, but to be happy. The US Declaration of Independence does not mention King George the III by name. But near the start it does refer to “the present King of Great Britain.”

From that point on, the document talks about “He.” It enumerates a long list of abuses, which may very well sound all-too familiar to reporters, pundits, voters and protesters who have followed the “injuries and usurpations,” to borrow Jefferson phrase, of the Trump administration. Jefferson noted the king’s “obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners” and for “refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither.”

Jefferson also noted that “He has affected to render the Military independent and superior to the Civil Power” and has “sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance.” What Jefferson doesn’t talk about and that he would have to add were he alive today would be the role of the mass media in the “establishment of an absolute Tyranny” and the fomenting of violence and hatred toward women and people of color.

As we celebrate July Fourth this year it behooves us to remember that The US Declaration of Independence inspired anti-imperialist movements around the world, especially in Vietnam, and that the document is no relic or artifact only or merely of historical interest and curiosity, but a living breathing manifesto mean to excite, rally and rebel.

The post No Kings, No Empires: Thomas Jefferson, Ho Chi Minh & Declarations of Independence appeared first on CounterPunch.org.