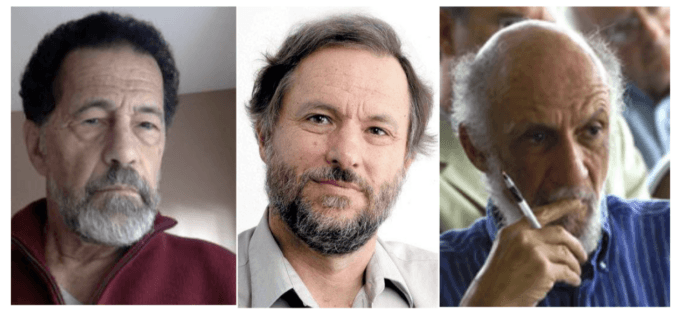

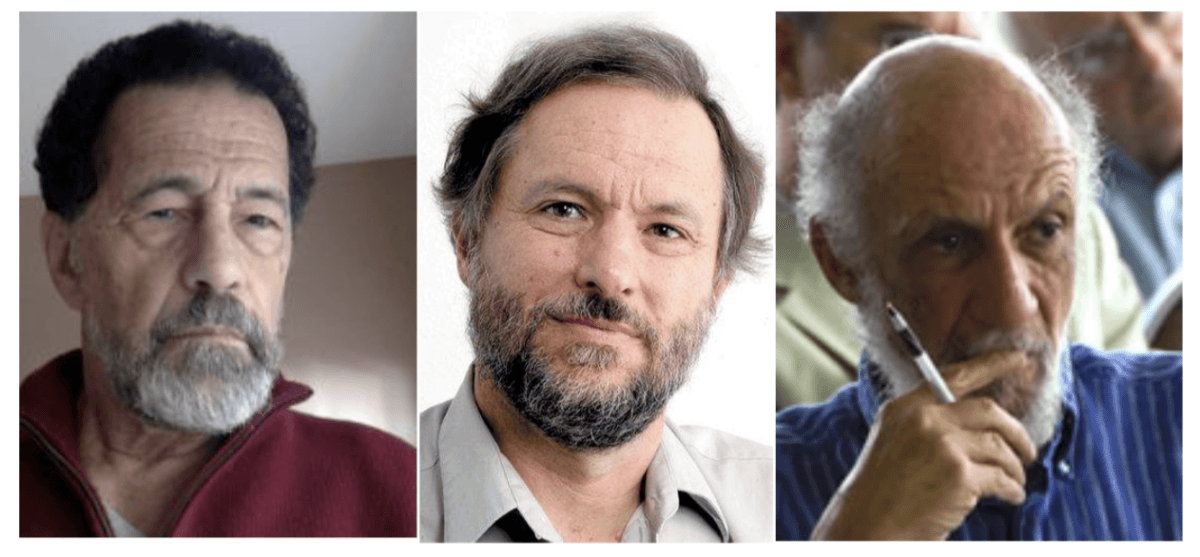

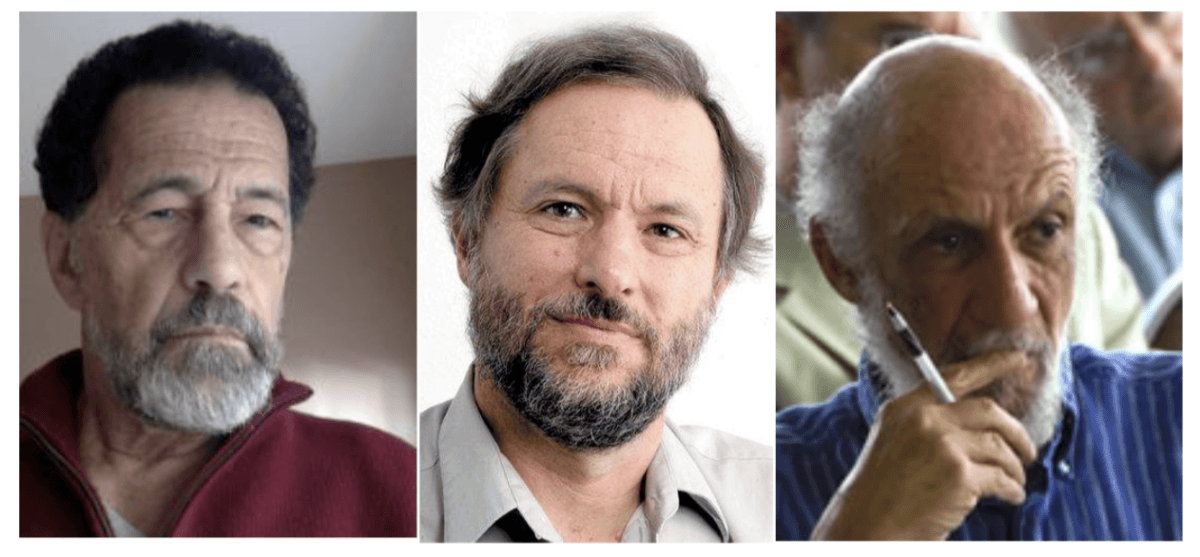

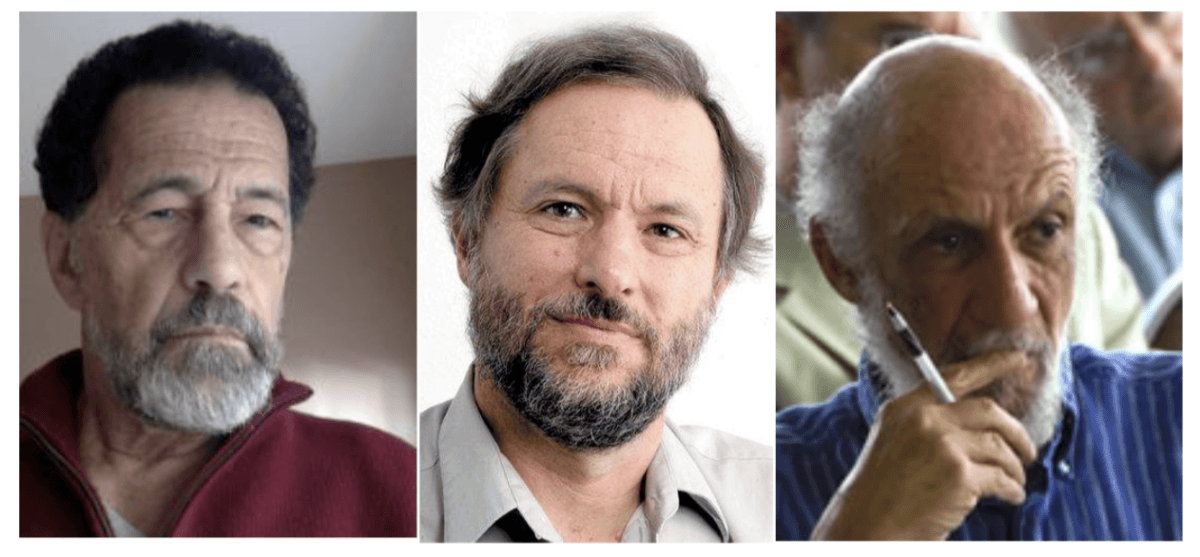

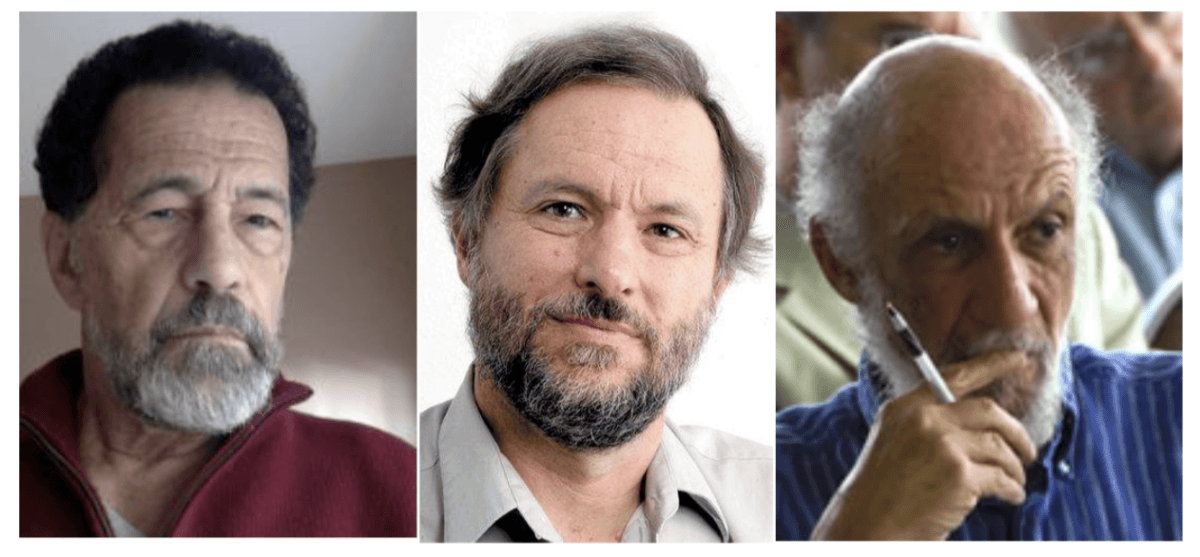

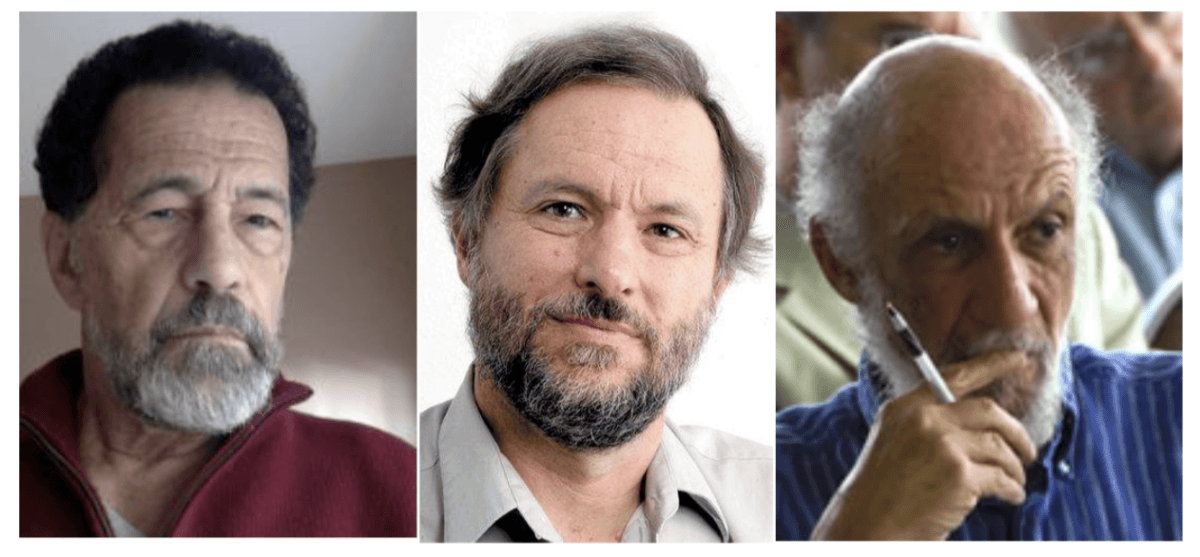

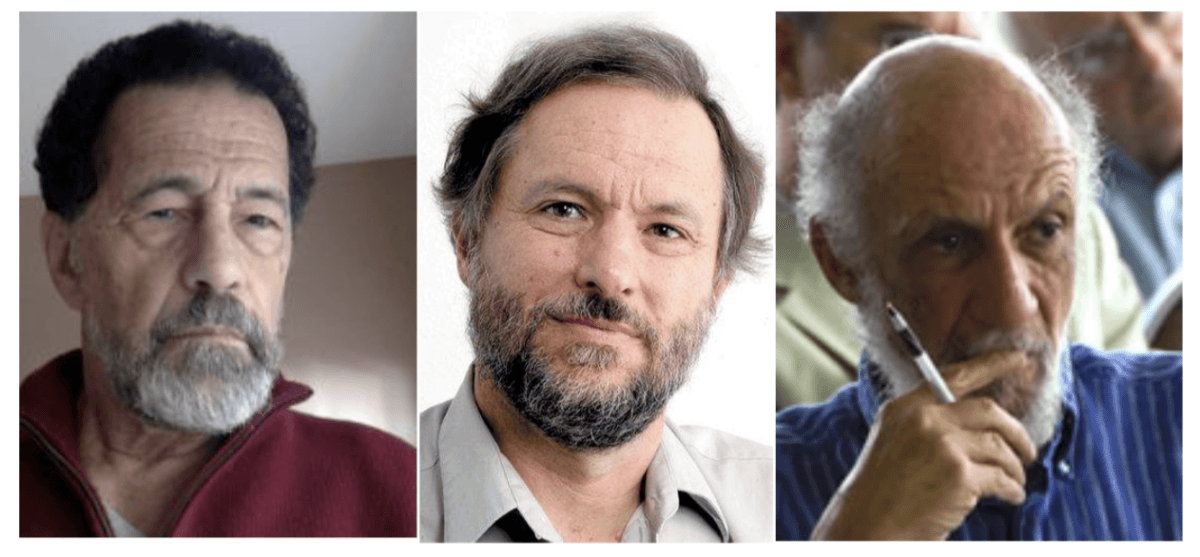

Lawrence Davidson, Stephen Zunes, Richard Falk.

In this latest and extensive discussion on U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear sites, CounterPunch features international relations scholar Stephen Zunes, Middle East historian Lawrence Davidson, and legal expert and former UN rapporteur Richard Falk, to explain the dynamics of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East with a focus on the Trump administration.

This conversation addresses several themes: the continuity of US imperialism, the strategic use of Israel as a proxy, the decline of democratic accountability and erosion of international law, the challenges facing civil society, and the need to construct more ethical frameworks for evaluating foreign policy. Lastly, we focus on the most recent US/Israel/Iran strikes, and their individual and collective goals.

Part 1: US Policy Toward Iran & the Middle East

Daniel Falcone: Can you explain the ways that Trump and American foreign policy toward the Middle East and Iran has continued its colonial path in distributing hard and soft power to the region? What might escalation look like?

Lawrence Davidson: Despite the isolationist mood of a segment of Trump’s supporters, the assumption among most of the “ruling economic class” is still that the U.S. must assert control over markets and resources. Thus, there is no reason to expect a significant diminishment in overseas adventures (though as explained below, how these are prioritized in the U.S. is a function of lobby power).

Indeed, Trump’s rather disgusting mimicking of Mussolini and Hitler by asserting unilateral claims to the Panama Canal, Greenland and even Canada is just a modern twist, albeit an embarrassing one, on U.S. colonialism.

Trump, of course, has a unique approach to this issue. He wants to assert control, and he will try to do so with a lot of bluster. His recent lecturing of Iran and Israel is a good example. Trump’s problem is he has trouble staying consistent. His attention span is short, and he is susceptible to consistent lobby pressure.

Stephen Zunes: The bombing of Iran is the logical extension of the 2002 U.S. National Security Strategy which essentially made the case that the United States would not tolerate regional powers challenging its hegemony in important regions like the oil-rich Middle East. After the overthrow of Saddam in Iraq in the 2003 U.S. invasion and the ouster of Assad in Syria by his own people last year, Iran is the only recognized state to resist effective U.S. control of the entire region.

When we think of the obsession U.S. policy makers have had with Cuba for the past 65 years and with Nicaragua and Chile in previous decades due to their resistance to U.S. domination, it’s not surprising that a large, relatively powerful, and resource-rich country like Iran would become such a focus. And, given the reactionary and authoritarian nature of the regime, its isolation in the region, and its unpopularity among its own people, it has become a perfect foil.

Let’s remember that Trump was never antiwar; he just opposed other people’s wars. He has always believed in war making to advance U.S. hegemony. His claims of being antiwar were as disingenuous as his claims he would stand up against Wall Street— he recognized that it was the best way to win over white working-class voters who had seen how Democratic hawks like Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden supported sending their kids to die in Middle Eastern conflicts.

Israel and its supporters are useful allies in implementing this policy, but they are not the source of it. Given the Iraq debacle, Israel has been utilized as a surrogate in a similar manner, like when the U.S. tried to use the Shah in the 1970s, advancing U.S. interests through wars without sacrificing American lives. Israel’s attacks on Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, and Iran make it so the United States only needs to intervene directly in extraordinary circumstances, such as in delivering 30,000-pound bombs safely from a high altitude.

As German Chancellor Friedrich Merz put it, “Israel is doing the dirty work for all of us”—a disturbing description in that it conjures up how, during the Middle Ages and other times in European history, the ruling class used some Jews to do the “dirty work” (i.e., money-lenders, tax collectors) so they could later be scapegoated rather than allow the masses to go after those who really had the power. Using Israel to attack the West’s enemies in the Middle East follows this pattern. Already, we are hearing some war critics insist that “the Zionists” are somehow forcing an otherwise reluctant United States and Europe to support wars of aggression rather than recognizing Israel’s role as that of a proxy for Western imperialism, a chorus which will likely increase should the United States be dragged down in an ongoing military conflict with Iran.

Washington has long acknowledged Israel’s role of a surrogate. President Biden has stated that “If it weren’t for Israel, we’d have to invent them.” Former Secretary of State Alexander Haig referred to Israel as our “unsinkable aircraft carrier.”

If the goal was simply to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon, which was the focus of the Obama administration, Trump would not have abrogated the Joint Comprehensive Program of Action (JCPOA, or “the Iran nuclear deal.”) By pulling out and reimposing sanctions, Trump effectively provoked Iran into enriching uranium to a degree that could someday potentially lead to weaponization and thereby provide a pretext for war. The actual goal, therefore, has been to weaken Iran as much as possible, and Israel was quite willing for its own reasons to play along as well. Indeed, Israeli air strikes went well beyond targets related to its nuclear program and Washington supported them in doing so.

I met with then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif in Tehran in 2019. He explained how it took nearly a decade of posturing and two years of intense negotiations to create the JCPOA, signed by seven governments and endorsed by the United Nations. He noted how he met with then-Secretary of State John Kerry no less than 50 times to go over the draft line by line. The idea that Trump could impose an even more restrictive agreement simply by demanding it was at best naïve and more likely just an excuse to go to war. Indeed, nuclear talks had resumed and were ongoing when the U.S.-backed Israeli war on Iran began. Neither the United States nor Israel wanted them to succeed.

The U.S. bombing of Iran, therefore, was not ultimately about nuclear policy or about Israel. It’s about hegemony. That Iran decided to launch only a limited response is a great relief. Though Israel had damaged Iran’s offensive capabilities, they still had enough weapons to do a lot of damage to U.S. assets. The United States has 40,000 troops within a couple hundred miles of Iran, easily within range of not just Iranian missiles, but drones and other weaponry. Iranian proxy militia in Iran could target U.S. bases.

The U.S. Navy is just off the Iranian coast, which could have also been targeted, and the Iranians could have attempted to close the Strait of Hormuz, crippling the world oil supply and threatening the global economy. Trump, meanwhile, explicitly threatened to unleash “a tragedy for Iran far greater than we have witnessed over the last eight days” if Iran retaliated.

Richard Falk: To gain perspective on the present alarming situation, I begin my response by taking note of the U.S. foreign policy response to the Suez Operation of Israel, UK, and France during the Eisenhower presidency in 1956. This was both the first, last, and only occasion on which the U.S. Government adopted a position that distanced itself from a colonialist initiative in the Middle East or anywhere. It was represented the only foreign policy challenge in which the U.S. gave priority to its legal commitment to uphold the UN Charter even when its constraints were inconsistent with its geopolitical alignments both with its NATO partners and Israel since the end of World War II and remains so fifty years later. It was particularly impressive at the time because Nasser’s Egypt was hostile to the West and a harsh critic of Israel statehood at the expense of Palestine, and beyond all this was on friendly terms with the Soviet Union at a time of rising Cold War tensions.

In a superficial sense, the U.S. response to the Suez Operation demanding withdrawal from Egyptian territory was consistent with its leadership in the UN after North Korea attacked South Korea or at least seemed so at the outset of the Korean War as the defense of South Korea was given legal authorization by the UN, including the Security Council. This was only possible because the Soviet Union was boycotting the UN at the time because of its refusal to seat China’s Peoples Republic as representing China and could not cast its veto to block UN support for South Korea. The Soviet Union learned its lesson, returned to the Security Council, and never again boycotted the Organization.

Yet the Korean precedent is quite different as the U.S. tends to resort to a legalistic approach whenever its adversaries violate Charter norms on the use of international force, and no time else. North Korea as a hard-core Communist country was an adversary and for this reason appeals to the UN appeals by the West, like the U.S. immediate reaction to the 2022 Russian attack on Ukraine. Both in the Korean and Ukrainian wars recourse to force was provoked by the West-oriented governments, especially the U.S., but covered up by influential international media platforms.

It is notable that the deep state, and its visible manifestations in the Council on Foreign Relations and the Washington think tanks, faulted this U.S. response in 1956 because it mistakenly adhered to international law at the cost of weakening its alliance relations, which was interpreted to mean weakening strategic national interests that were associated with the central issue of unconditionally opposing the Soviet Union and all direct and indirect extensions of its influence beyond its geopolitical borders.

This post-mortem critique of U.S. statecraft prevailed, and the U.S. Government never again sacrificed its strategic interests out of deference to international law or the UN in the Middle East, or elsewhere. In the early stages of Israel’s existence it meant balancing relations with Israel as a settler colonial exception to decolonizing historical worldwide trends against the pragmatic priority of securing for the West assured access to Gulf oil at stable prices, which meant a maximum effort to minimize Soviet influence even at the risk of major warfare and also a maximum effort to avoid antagonizing the anti-Israeli stance of Arab governments during the remainder of the 20th century.

Long before the Suez Crisis the colonialist penetration of the region was introduced in a somewhat disguised Orientalist form by the Balfour Declaration of 1917 in which the British Foreign Secretary pledged support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine without even a pretense of consultation with the resident Arab population of post-Ottoman Palestine. The Balfour Declaration represented an expression of overt colonialist arrogance to solve European problems associated with antisemitism at the sacrifice of Palestinian rights of self-determination undertaken without any show of concerns about the impassioned grander ambitions of the Zionist Movement that went far beyond establishing a non-governing homeland in a foreign sovereign state even at this early stage.

British motivations included a typical application of the divide and rule tactics of colonial governance through encouraging Jewish immigration as a check on rising Palestinian nationalism. It backfired as anti-colonial nationalism flourished, the Zionist Movement shifted its focus from gratitude to Balfour to the adoption of armed struggle against the British colonial administration in Palestine. The legacy of these several varieties of colonialism policy was to inflict on post-1945 Middle East life a continuous series of wars, prolonged tensions that solidified Israeli autocratic rule dependent on the U.S., and worst of all, the embodiment of the Zionist domination of the Israeli state which entailed systemic human rights violations, ethnic cleansing, culminating in apartheid and genocide, and the establishment of a sophisticated and ruthless settler colonial state that made Palestinians persecuted strangers in their own homeland, victimized by a lethal fusion of apartheid and genocide.

This balancing of strategic interests was tested, and reaffirmed in the context of the 1967 War in which Israel lost its identity as a strategic burden worth protecting for a variety of political reasons to become a highly valued partner in ensuring Western control of the region despite the formal independence achieved by Arab national movements in the MENA region that included the North African states. From this time forward to the present the U.S. never challenged Israel’s use of force in the region, including its flagrant violations of the Geneva Conventions in its administration of the Palestinian territories of East Jerusalem, West Bank, and Gaza occupied by force during the 1967 War.

There was a naive attempt to find a solution to the Israel/Palestinian conflict by way of the framework set forth in Security Council Resolution 242 adopted shortly after the war end, which wrongly anticipated Isreal’s early withdrawal from these Palestinian territories after minor border adjustments. As we now know more than half a century later this withdrawal never happened and was probably never contemplated by the Zionist leadership that held sway in Tel Aviv. Given this unfinished nature of the expansionist Israeli agenda as marching in lockstep with the imperial nature of the U.S. approach to the Middle East.

The result was a gradual normalization of these realities that achieved a bipartisan consensus second in solidity only to the anti-Communism of the Cold War. In effect, the U.S. became the replacement for the UK and France colonial management of Western political and economic interest in the Middle East, whose policies were increasingly at odds with support for international law, UN majority sentiments, and the essential decolonizing ethos of national self-determination. The growing dependence of Gulf Arab governments on stabilizing relations with the U.S. became evident in the aftermath of the 1973 War in which the temporary prohibition of oil sales to the West gave rise to long lines at U.S. gas stations and reactive scenarios of U.S. intervention dramatized on the cover of a leading national magazine with an image of American commandos parachuting in Gulf airspace to take over the production and distribution of oil and natural gas to the West.

Subsequently, the leading Arab governments and the U.S., and even Israel, informally made a mutual accommodation, acknowledging a Palestinian right to statehood, but turning a blind eye to Israel occupation settlement policies designed to make the establishment of a viable Palestinian state impossible, dismissed by Palestinian liberation politics as ‘breadcrumb diplomacy’ or a new version of South African Bantustans.

Part 2: Civil Society Watches Another War

Daniel Falcone: What do you foresee the role of civil society and intergovernmental organizations in the coming days and weeks regarding Iran?

Lawrence Davidson: There will be some protests and much analysis. However, it may be that the die is cast. It will be a hard sell to make international law and human rights effective guides for state behavior. If the historical record is predictive, they will not again serve as guides until we experience some sort of sobering catastrophe.

As to Iran specifically, its war of attrition with Israel will continue. Despite the spin of U.S. reporting, Israel will be the first to face a real crisis. This will force the U.S. back into the war to halt Iranian attacks. The Zionist lobby will insist on this. The Zionists will not draw any of the obvious lessons from the Iranian attacks.

I must say it was [eye-opening] for me to see Israel get some of the same punishment they have inflicted upon Gaza. One would hope they would learn an important lesson from this experience and perhaps there are many Israelis who have drawn the correct lesson. But Netanyahu and his cohort are probably oblivious.

Stephen Zunes: Unlike the Bush administration and its allies in the media, who put great effort into convincing Americans to support the war on Iraq, Trump has put little energy into convincing Americans to support war on Iran. His speech Saturday evening seemed largely improvised and lasted only four minutes. It’s as if the U.S. has become so deindustrialized they can’t even manufacture consent anymore.

On the positive side, polls prior to the U.S. bombing showed overwhelming majorities opposing the United States entering the war, with barely 15% supporting it. Unlike the first couple years of the Vietnam War and the first several months of the Iraq War, we don’t have to work to get most Americans on our side. They already are. Even some pro-Israel groups (i.e., J Street, New Jewish Narrative) have come out against war with Iran, demonstrating there are divisions even among Zionists.

Unfortunately, American civil society is badly distracted simply in defending itself from an increasingly authoritarian state and the havoc it has unleashed against minorities, immigrants, education, the environment, and government itself. Mobilizing against a war, particularly one that does not involve American ground troops, in the face of all the other political crises would be challenging. Furthermore, unlike the 1980s when activists were inspired to defend a promising if imperfect socialist experiment in Nicaragua against a U.S. assault, Iran is a decidedly reactionary regime which most of its own people would like to see toppled (albeit not by a foreign power).

Little can be expected from intergovernmental organizations either. There is obviously the threat of a U.S. veto of anything the UN Security Council would try to offer. More generally, Iran is seen in the region and beyond as a something of a pariah state, so few nations, particularly in the West, can be expected to stick their necks out in defense of international law, even if Iran’s grievances are valid.

Richard Falk: If interpreting this question as pertaining to Europe and North America, as well as Israel and Palestine, it is anticipated that anti-war civil society organizations will be very active in opposing the attacks on Iran’s nuclear program and its facilities devoted to enrichment of uranium. If the war goals are extended to regime change by Israel and supported by the U.S., such opposition might be expected to grow. Trump’s foreign policy identity was established by opposition to any future U.S. involvement in ‘forever wars’ and state-building undertakings (that failed at great expense most spectacularly in Iraq and Afghanistan) by invoking a neo-isolationist foreign policy sloganized as ‘America First,’ while being sustained by militarist domestic rule and neo-fascist ideology incorporating unconditional support for whatever Israel undertakes, however, unlawful, cruel, and risky.

In the context of the evolving unprovoked aggressive war against Iran, civil society and the UN are confronted by an almost total inversion of the posture taken in the Suez Crisis. With respect to Iran, the violation of UN Charter red lines designed to uphold war prevention commitments, the U.S. and the West dismissive attitude toward the relevance of international law in the event of recourse to non-defensive warmaking. Here the rationalization for Israel’s aggression, addressed sympathetically in Western media, is based on alleged threat perception relating to an apprehended Iranian possession of nuclear warheads. A more reasonable view of the nuclear dimension of national security would situate the threat on Israel’s side of the bright red line.

After all Israel has a covertly acquired nuclear weapons arsenal of 300-400 warheads as facilitated by Western secret assistance and as purged from the periodic nonproliferation review program agendas. While Iran is a generally complying party to the NPT Israel has never joined and has rejected efforts to establish a nuclear free zone in the Middle East, a proposal ardently supported in the past by both Iran and Saudi Arabia. Such a nuclear weapons free zone in the Middle East was repeated rejected by Israel and its Western backers. It would at least readjust the international debate if NGOs and the UN brought these realities into the light of day. As it is, the nuclear path chosen by North Korea would serve as a national security tutorial on the benefits of proliferation in the Nuclear Age. Despite hostility to North Korea and its acquisition of nuclear weapons capability, its nuclear program and nuclear weapons arsenal were never attacked. In contrast, Libya, Ukraine, and now Iran have been presumably attacked because they lacked a nuclear retaliatory capability. The lessons to be drawn are ominous.

Beyond the nuclear dimension, it would be important to understand that U.S. support for Israel in relation to Iran is partly based on a racist containment rationale that carried into practice Samuel Huntington’s 1990s anticipation of a ‘clash of civilizations’ along the fault lines of the Middle East separating Islam from the white West. From this perspective Israel is integral to Western post-colonial imperialism, manning the frontline of Islamic containment, and doing the dirty work of the West backed up by the U.S. to the extent necessary. Iran to an extent conspired by vowing to destroy Zionist governance in Israel and encouraging street chants along the lines of ‘death to Israel, death to America.’

Part 3: The War Machine and the Lobby

Daniel Falcone: To what extent does domestic political pressure, such as lobbying from interest groups or bipartisan consensus limit the reassessments of the U.S. war machine?

Lawrence Davidson: I don’t think that the elected leaders of the U.S. consciously say to themselves, “We are colonialists and that is our path.” True, they are racists: personified in a series of recent elected leaders such as Reagan, the Bushes, Biden and now Trump. But remember in many ways Trump and the others are “us.”

After all, these horrific “leaders” were elected by an appreciable subset of the U.S. population. But once elected they were all enveloped in a system wherein policy is the product of dominant interest groups. The most dominant one, in terms of foreign policy, is the Zionists.

It has been over 80 years since the U.S. government as such has overseen its own Middle East policy, The Zionist lobby is in charge, because that is how our modern system works. The same special interest domination is to be found in the foreign policy toward Cuba, and, for that matter, the domestic policy toward gun control, abortion, etc. Each has its own dominant lobby. Want to change policy? Well, it is insufficient to change the leader or the party. One must destroy the relevant special interest.

Stephen Zunes: When U.S. intelligence reports reiterated that Iran was not in fact working on nuclear weapons, instead of taking the Bush administration approach of rewriting the intelligence to conform with his policy, Trump simply insisted that it was wrong. He even repeated the long-bunked argument that Iran was responsible for a thousand American deaths in Iraq. There hasn’t, therefore, been much pressure from the military and traditional national security establishments to go to war. Unfortunately, few Democratic leaders in Congress have challenged the Trump administration’s talking points either.

As with Israel/Palestine, there is a huge gap between the views of Democratic voters and their elected officials. Chuck Schumer, Hakeem Jeffries, and other Democratic leaders came out in support of Israel’s unprovoked attack on Iran, insisting it was for “self-defense.” Their repeated mantra that “Iran must not be allowed to develop a nuclear weapon” without simultaneously demanding a return to the JCPOA would seem to indicate an openness to military solutions over diplomatic ones, apparently believing that Obama’s approach (a binding international treaty Iran already agreed to that would make it physically impossible for Iran to ever build a nuclear weapon) is inadequate while Trump’s approach (make war, even if it doesn’t actually prevent them from doing so) is somehow more valid.

Given how most Congressional Democrats have had no problem with Netanyahu’s criminal warmaking in Gaza, it’s not surprising that Trump thought he could get away with launching an illegal war as well. Fortunately, he is getting some pushback from even the more hawkish Democrats, though primarily because of his refusal to abide by the War Powers Act, or even the U.S. Constitution, in ordering the attack without the required consent or even notification of Congress. It is questionable whether Congress will follow through with any concrete action, such as impeachment, which would be quite appropriate.

Certainly, AIPAC and some other pro-Israel groups, including rightwing Christian evangelicals, have been pressuring for war with Iran for years, but their clout primarily has been with Congress, not the executive branch, and Congress has largely been frozen out of the decisions regarding Iran (until very recently). There is little indication that they were decisive in Trump’s decision to join the war. Meanwhile, the calls and emails to Congress this past week have been overwhelmingly negative, serving as a reminder of the public mood and potentially laying the groundwork for a more proactive Congress on foreign affairs in the face of years of consolidation of power in the executive branch.

Richard Falk: There is a rather unnoticed paradox that underlies U.S. foreign policy in the Trump Era. On the one side Trump’s coercive maneuvers are opening the gates to the collapse of democracy and the onset of an American variant of fascism. On a second side, Trump as the overt and in-your-face autocrat seems captive to Zionist pressures as mounted by well-funded pro-Israeli lobbying by AIPAC, by the distinct worldview of Christian Evangelists that fuses unconditional support for Israel with exclusionist antisemitic motivations similar to the attitudes that underlay the Balfour Declaration, and by far right politics that admired Israeli Prussianism while demeaning the Global South.

On the third side, private sector profitability among arms producers benefits from U.S. engagement in foreign wars and regime change undertakings are seen as opportunities rather than costly misadventures. On the fourth side, groupthink in foreign policy advisory elites and the Potomac River think tanks exclude from their ranks even realist voices such as those of John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt who counsel prudence and a more nationalist and restrained conception of foreign policy. These factors in various ways obstruct critical reassessments of U.S. militarist foreign policy, generating the amazing stability of bipartisan pro-Israel policy even when American arms are used to commit atrocities and Crimes Against Humanity.

This gives rise to curiosity about the American deep state, centered in the CIA bureaucracy. Does it share the group think version of a realist US foreign policy, or is it more critical along Mearsheimer/Walt modes of thinking? It is beyond reasonable horizons of hopefulness to imagine that deep state operatives favor a more law-oriented, justice-driven U.S. foreign policy agenda. Yet it might be deep state rising concerns about long-range global challenges, including unwanted, catastrophic recourse to nuclear war and global warming calamities of climate change, to favor a more cooperative approach to inter-governmental relations to achieve functional adjustments that if left unattended spell almost certain doom for the country, and even planet. Such a viewpoint if at all present among deep state regulars will surely draw lessons from the maladroit approach being taken by the U.S. to Middle Eastern stability and global problem-solving. It is hard to estimate whether deep state insulation from special interest lobbying tends to produce a more knowledge-based approach to foreign policy or whether its orientation is as shortsighted as its elected leaders whose views are much affected by populist mood swings. Of course, Trump is an extreme instance of policy driven by political intuition, and contemptuous of experts and time-honored constraints on the exercise of power, above all recourse to war.

Part 4: Global Norms in Ruin

Daniel Falcone: Given the battered state of the global human rights discourse and international law, how can scholars and citizens alike bring hope and a consistent framework for evaluating foreign policy?

Lawrence Davidson: I don’t have a very optimistic answer to this question. Most people are very local in their understanding of the world-local geographically and in temporal terms. In the face of this, it is our job to keep the memory and potential of international law and human rights alive. In this regard I think Richard Falk is a great example.

Stephen Zunes: I never imagined back during my radical youth, with my idealist view of building a progressive egalitarian society, that I would today be fighting what may be a losing battle simply to save the liberalism of my parents’ generation and the belief that, through the establishment of the United Nations system, the nations of the world could prevent future aggressive war and that most of the world’s governments — at least among the liberal democracies, would recognize their obligation to uphold international law. As we have seen in the case of Iraq and subsequently, the U.S. government, often with bipartisan support, can get away with making war on countries on the far side of the world that are no threat to us. We have also seen how both the Trump and Biden administrations are willing to formally recognize the illegal annexation of territories seized by military force. By contrast, even Reagan was willing to support UN Security Council resolutions opposing Israel’s illegal annexation of Syria’s Golan region and supporting Western Sahara’s right to self-determination.

Discourse on human rights and international law in Washington have swung way to the right in recent decades. The bipartisan support for Israel’s war on Gaza strongly suggests that if today’s Democrats were in power in the 1980s, they would have supported the death squads in El Salvador, the Contra terrorists in Nicaragua, and the genocidal war on the indigenous peoples in Guatemala. They would have probably attacked the International Court of Justice, other UN agencies, and Amnesty International for addressing human rights abuses by U.S. allies, as they have done in the case of Israel.

Yet the American public, if polls are to be believed, feel even stronger about protecting human rights and the rule of law than ever. The double standards regarding Russian attacks on Ukrainian hospitals (and Iran’s attack on the Israeli hospital in Beersheva), for example, in light of the destruction of dozens of Palestinian hospitals in Gaza, are so flagrant that millions of Americans who might have used these other atrocities to embrace U.S. policy now respond with appropriate skepticism. The inadmissibility of expanding territory by force, used to justify U.S. support for Ukraine, rings hollow considering U.S. recognition of Israel’s illegal annexation of Syria’s Golan Heights and Morocco’s illegal annexation of the entire nation of Western Sahara.

Previous presidents at least pretended to care about human rights and international law, even if required extreme verbal gymnastics and flagrant double-standards to do so. Trump, by contrast, doesn’t ever pretend to care about them.

This provides an opening for civil society to demand a renewed commitment to the international legal order, particularly given how the U.S. refusal to live up to these commitments have generally not ended well, e.g. Iraq. Indeed, if the United States, with its enormous military, economic, and diplomatic power, can refuse to play by the rules, why should anyone else? If the moral and legal arguments are not compelling enough, an enlightened utilitarianism, recognizing how U.S. failure to live up to these standards has provided an opening for despots and terrorists, might spark a renewed commitment to human rights and international law.

Richard Falk: It is crucial that both scholars and citizens point to the Western abandonment of the war prevention and global security aspirations of the architects of the post-1945 world order. This abandonment began, of course, far earlier than the period since the Soviet collapse in the tactics deployed by both sides in the Cold War, involving state terror to defend spheres of interest and eliminate hostile political actors and movements.

The embrace of Israel’s genocidal retaliation to the events of October 7 brought these geopolitics of lawless violence to a transparent climax accompanied by an unattended humanitarian emergency and now followed by the launch of an aggressive war against Iran. Despite rising civil society concerns the UN was kept on the sidelines, and Western officialdom has refrained from naming Israel behavior as ‘apartheid’ followed by ‘genocide,’ indeed selectively punishing those who shouldered burdens of talking truth to power. In the post-attack Iran context, the corporatized media gives ample outlets for Israeli spokespersons and advisors while virtually silencing global voices of conscience that bring to the fore concerns about war, law, justice, and human rights. Much of this recent weakening of democracy proceeds from what appears to be entirely voluntary self-censorship.

Given the depth of global challenges, these unheard voices have a vital message that relates to species wellbeing, and possibly survival. It adds up to the imperative of a restorative push for global normative reform. The priorities of such a renewal of the global normative agenda could begin by focusing on denuclearization, empowerment of the UN General Assembly, the elimination of the Security Council veto, and decreeing compulsory recourse to the International Court of Justice at the behest of either party to an international dispute as well as the relabeling of ICJ ‘Advisory Opinion’ with new language implying ‘Authoritative Judicial Rulings.’

Part 5: Managing Conflict Without Solutions

Daniel Falcone: Looking at the recent strikes, the stated goals were to delay enrichment, restore deterrence, buy time for diplomacy, and dismantle Iranian programs. It looks like Tehran won’t stop producing energy. How do you assess the long-term strategic value of this operation, and does this pattern suggest a placing of managing escalation above resolving them?

Stephen Zunes: Regarding the goals:

There was nothing to deter, because Iran was not threatening anybody and they were on the receiving end of an unprovoked attack. There was no need to buy time for diplomacy, because Iran was still years away from the capacity to build a nuclear weapon and diplomatic talks were ongoing. And it was never possible to dismantle Iran’s nuclear program through military force. The scientific knowhow and the resources to rebuild will always be there.

The one partial success from the twelve days of intense warfare was that it may have delayed enrichment for a few months.

The Trump administration and its bipartisan supporters in Congress, then, want to convince people that the killing of nearly 1,000 Iranians (primarily civilians), the substantial damage done to even non-nuclear and non-military targets in Iran, the resulting (lesser but still substantial) damage done on the Israeli side by Iranian missiles, the illegal assassinations of scientists and military leaders, and the further weakening of the international legal order through the launching of an unprovoked war was worth postponing the resumption of Iran’s uranium enrichment program until sometime this fall.

There was therefore no real strategic value. Indeed, as we have noted above, this wasn’t really about Iran’s nuclear program, since returning to the JCPOA would have created a rigorous inspection regime that would have prevented Iran from militarizing its nuclear program. It was about weakening Iran.

Physical damage is not a measure of a regime’s strength, however, and the Islamic Republic is probably stronger because of defending the nation against what even regime opponents recognize as a war of aggression. People tend to rally around the flag, particularly if the country is subjected to foreign attack and governments are more likely to get away with greater repression. This is why virtually all prominent pro-democracy activists opposed the war. Advances by both reformers within the system and those challenging it from the outside may now be reversed because of the perceived emergency. If regime change was also a goal, that has been set back as well.

I don’t expect a return to level of warfare we’ve seen over the past two weeks, but we might see Israel engaging in occasional air strikes if the Iranians try to rebuild their damaged facilities, followed by some Iranian missiles being fired into Israel. Such intermittent warfare will keep the region on edge and encourage further militarization. Unlike the JCPOA, which contributed greatly to regionally stability prior Trump destroying it, the U.S./Israeli war on Iran has made the region more unstable and dangerous.

Lawrence Davidson: A couple of things stand out about the U.S. attack: 1) It was too limited to destroy the sites targeted. The damage was superficial. It is unclear if this was Trump’s intent or if the U.S. Air Force, enamored with its “bunker busting bombs,” felt one bombing pass would do it. 2) The Iranians were taking no chances and moved most of the material out of Fordow in the days before the attack. What this adds up to is some delay as production and enrichment are given new factory structures. But no apparent damage to the project as such.

There are those who believe this attack was all “theater”, but I am not sure. Trump gave in to immense Israeli/Zionist pressure to attack Iran. He was then probably told by the Air Force that one bombing pass would destroy the targets. That info. was wrong, but as it happened the operation did halt the cycle of escalation. Iran shot a final missile at the U.S. base in Qatar after telling both countries the thing was coming and that was that. Whether breaking the cycle was Trump’s intention or not, he decided to go with it. That was the final act (so far).

The U.S. operation did not have sufficient force to serve as any long-term strategic value. The Israelis, reassured that they can apply enough pressure to force Trump to act, are telling everyone that “the war is not over.” And we know that they are the wild cards in this whole affair. So, Israel might start the entire thing anew once it replenishes its stock of defensive missiles.

Richard Falk: There are two modes of perception relevant to U.S./Israeli strikes against Iran’s nuclear sites: (1) the prevailing Western mode of assessment that limits evaluation to the tactical and strategic success, or lack thereof, attributed to the joint Israel/ U.S. military operation; (2) a more critical mode of assessment that rejects the precedent of such a unilateral recourse to preemptive war justifications to address a foreign policy objective of questionable legality, political responsibility, and moral sensitivity.

Considering Operation Rising Lion (Israel) and Operation Midnight Hammer (U.S.) as a military operation configured to destroy Iran’s nuclear program by major attacks upon Iran’s nuclear sites. At present, the overall results including Iran’s shorter- and longer-term reactions to such violence encroaching on their territorial sovereignty and national security are not yet clear. There exists much uncertainty as to whether what is being described by the media as a ‘fragile ceasefire’ turns out to be a truce in a continuing and renewed military confrontation or is the prelude to a more stable and durable restructuring of relations between the three countries. Such a development would presumably lead to resumed negotiations by Iran with the U.S. with the objective of establishing agreed limits on Iran’s nuclear future, perhaps couple with Western sanctions relief. An Israel/Iran peaceful accommodation is more difficult to envision.

As far as an evaluation of the damage inflicted by the attacks, assessments vary. The three governments each claim success, Israel and the U.S. for their military operations, Iran for its retaliatory response, disclosing both capabilities to penetrate Israel air defenses and its display of restraint and composure reflecting prudential concerns with escalation of violence in the context of a limited war scenario. Whether the damage done to Iran’s nuclear program destroys or merely delays by a matter of months weapons grade enrichment of uranium remain a matter of controversy, disparate conjecture, and uncertainty. This inconclusiveness applies particularly to the deep underground Fordow nuclear site that was struck by a series of 30,000 pound ‘blockbuster’ bombs, which reportedly failed to explode at deep enough levels to destroy the nuclear facilities.

At issue, also, is whether Iran reacts by terminating its nuclear program, or contrariwise, rebuilds with renewed zeal and enhanced safeguards against a repetition of the 2025 coordinated attacks. It is also possible that Iran will also seize the opportunity to withdraw from the Non Proliferation Treaty accompanied by an announced willingness to revive support for a Middle Eastern Nuclear Free Zone (including Israel) that was rejected by Israel twenty years ago. If such a development is resisted by Israel, which is almost certain, then Iran could act provocatively by announcing its decision to acquire nuclear weapons, limiting its role to the deterrence of Israel.

(2) If a world order perspective is adopted, this recourse to a preemptive war validation for a use of international force that on its surface defies international law is a further defiant mode of serving strategic interests of Israel and the West that weakens the global normative order established at the end of World War II following a design that was developed by the U.S. Government. This design was deliberately weakened by conferring upon the major winning states in the war the right of veto to Security Council decisions together with limiting the authority of the more democratic General Assembly to recommendatory authority. It also assured the primacy of geopolitics by situating enforcement authority of judicial authority in the Security Council and by labeling International Court of Justice rulings in response to questions of law put to it by the UN General Assembly and other organs of the UN System as ‘Advisory Opinions.’

In this sense, the precedent set by unilateral attacks starting on June 13, 2025, the so-called ‘Twelve Day War’ were a further setback for the undertaking that reaches as far back as the Pact of Paris (1928) outlawing aggressive warmaking as well as the Nuremberg Judgment’s declaration of international aggression as a Crime Against Peace, what the tribunal called the worst of international crimes.

If this line of perception is restricted to the interaction of the three countries as to guardrails against both the spread of the weaponry and its threatened use, the results are decidedly negative. Israel, as noted, is itself a nuclear weapons state that has waged war widely against both the Palestinians living under their protective status as Occupier and the claim that Iran posed a security threat despite its capabilities to mount nuclear retaliatory options if deterrence fails. Israel’s disallowance of nuclear enrichment, even if reinforced by its reiterated of Iran’s official denial of any intention ever to acquire nuclear weapons would not be balanced to the slightest degree by an offsetting Israeli commitment to refrain from threat or use of the weaponry, or even by a tender of a no first use pledge. This kind of imbalance is expressive not only of Israel’s regional hegemonic ambitions, but of Western post-colonial imperial priorities in the strategic Middle East.

It is rarely commented upon, but the initial formulation of Operation Rising Lion, not only sought to launch a maximum attack on the physical facilities at Iran’s nuclear sites. It also explicitly aimed to undermine Iran’s capabilities to restore the program by seeking to kill top Iranian nuclear scientists, described as ‘the weaponization group.’ Such scientists were civilians, non-combatants, at prohibited targets even under conditions of legitimate warfare. This extends Israel’s practice of selected opponents of its settler colonial project in Israel, including cultural figures and leading activists, a further sign of contempt for International Humanitarian Law.

The post Updates on the Iran-Israel War: Conversations with Leading Analysts appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.