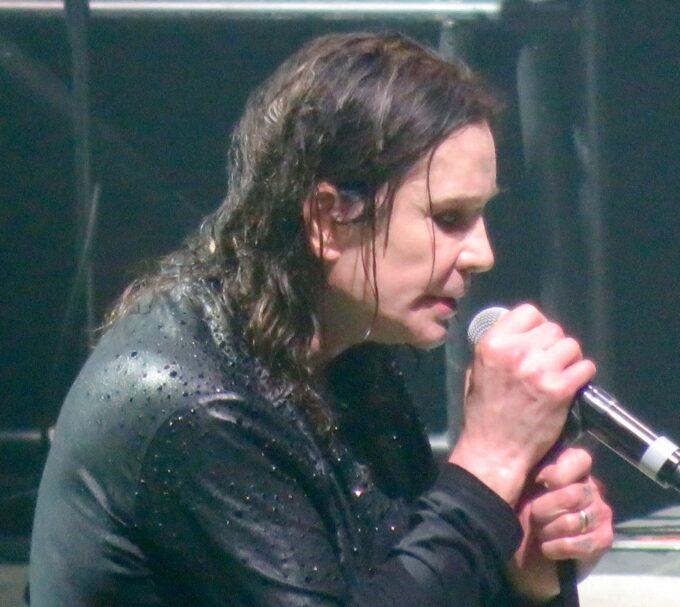

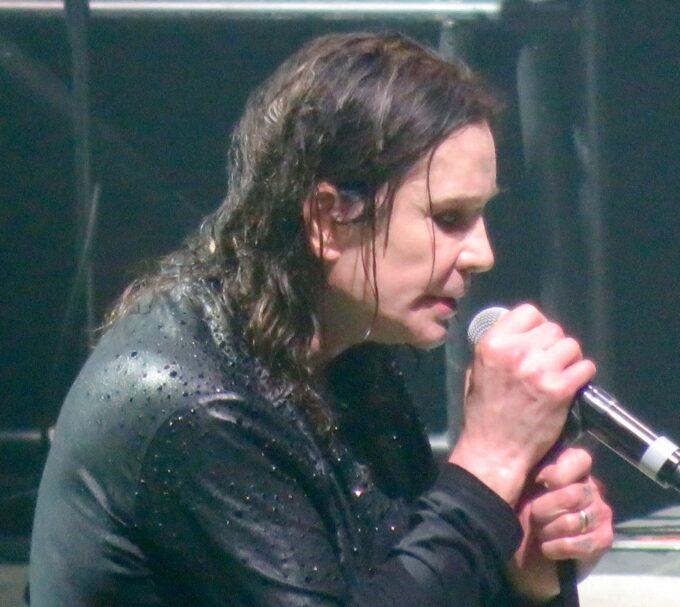

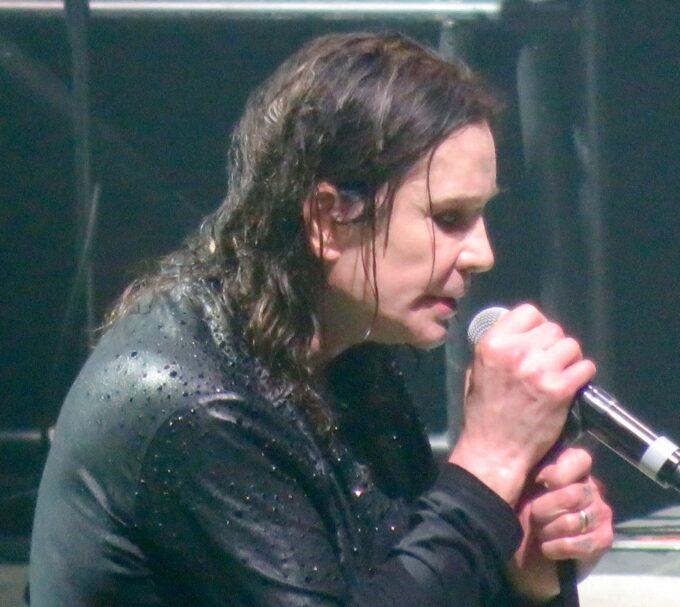

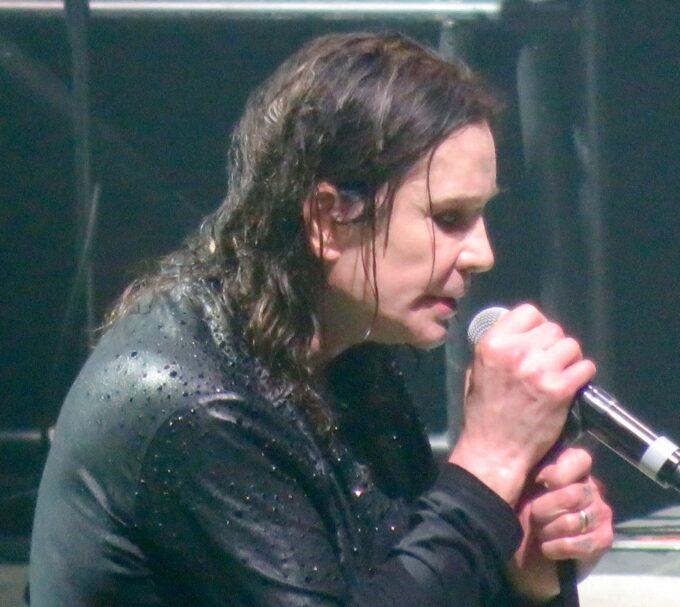

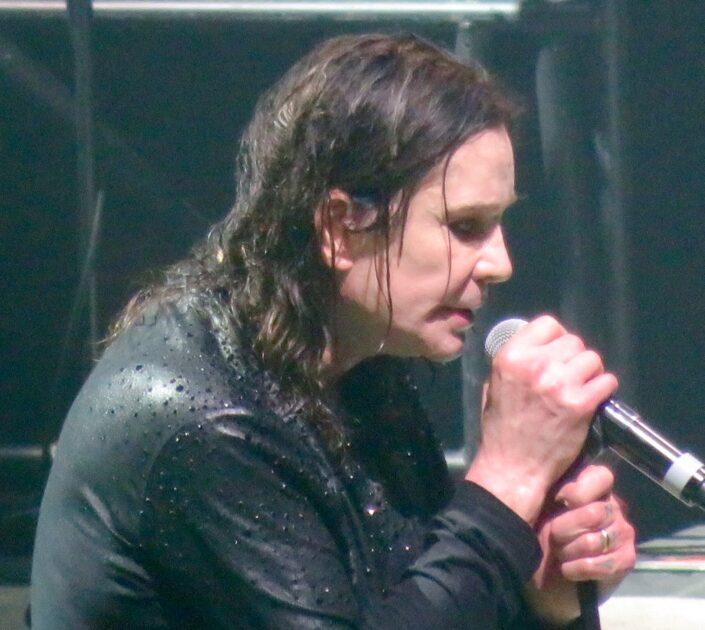

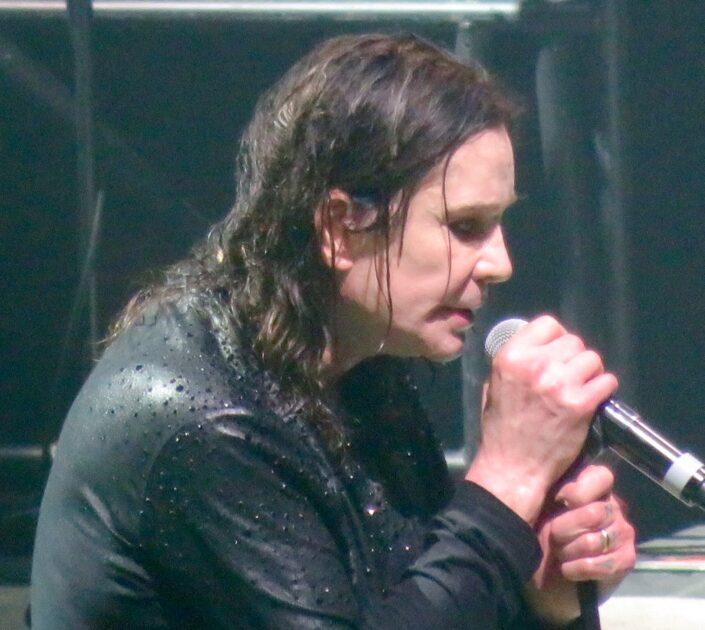

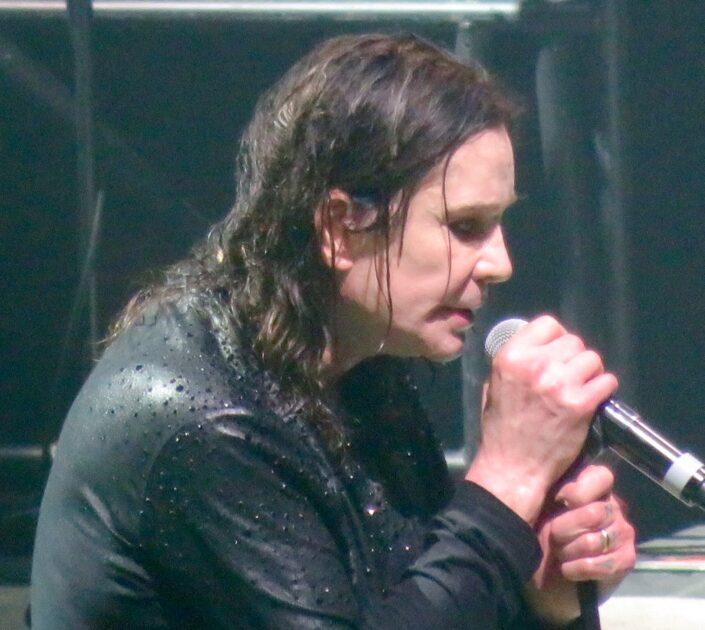

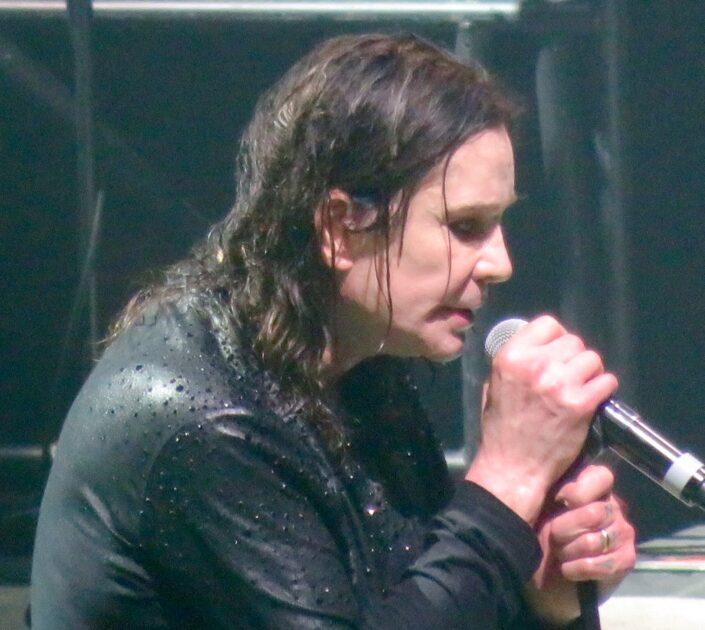

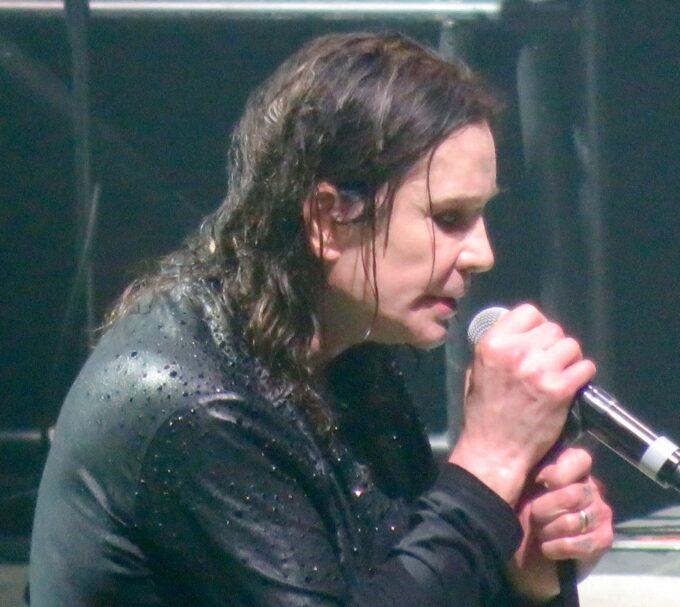

Ozzy Osbourne performing in Birmingham, England with Black Sabbath, February 2017. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0

My wife recently told our 23-year-old nephew about how Ozzy Osbourne bit the head off a live bat. It was in 1982 on the appropriately named, “Diary of a Madman,” tour. Blood dripped down the heavy metal dark lord’s chin to an enthralled, yet horrified audience in Des Moines, Iowa. Ozzy thought that the bat was fake, and grew exhausted with subsequent requests for him to use his teeth to decapitate winged creatures. In the immediate aftermath of his death, PETA issued a statement praising Ozzy for the “gentle side he showed to animals.” The bat-homicide was an unintentional anomaly, but it still became an immortal part of rock and roll lore. Our nephew was curious, surprised, and confused. He had never heard of anything so bizarre, a reaction he communicated with repetition of an inquisitive, “No!?”

23-year-olds have come of age in a stale and stagnant culture. It is the culture of the pre-packaged interview, the “social media consultant,” the Instagram filter, the carefully parsed public relations-penned announcement, statement, or apology, the focus group tested product, and the imperialistic, hegemonic algorithm, forever directing people what to consume, when to feel, and how to think. It is all dull, monotonous, and mundane drag; an endless bore that results in a sad status quo of late senior citizens, like the 76-year-old Ozzy Osbourne, being more fascinating and daring than young pop stars.

Here is a question: When was the last time you remember a pop star doing anything interesting? And by “interesting,” I don’t mean interesting to you, as tastes are subjective, but culturally interesting enough to generate conversation, and to make people respond like my nephew, “What!? No!?”

Pop stars are no longer exciting, adventurous, or innovative, because they no longer live or create as human beings. Instead, they actually self-apply the term, “brand.” In their ambition to become walking and talking, sentient incarnations of the golden arches, white swoosh, or gray apple, they cannot risk surprising their fan base, because surprise could lead to alienation, and alienation could lead to loss of profit. One journalist for the Guardian lamented that his celebrity interview subjects no longer meet in bars for a few drinks, but instead invite him to a hotel suite packed wall to wall with publicists, agents, handlers and unidentified nervous nellies who say, “You can’t ask that” or “you can’t answer that.” Of course, the control team is largely unnecessary, because the celebrities give scripted answers anyway. Their words are meticulously crafted to appeal to the broadest set of social media users. The same newspaper ran an interview with Kathryn Frazier, a “rock star whisperer,” who helps musicians acquire and navigate fame. A major part of the operation is rising to high levels of “influencer” stardom. In a culturally catastrophic inversion, marketing is no longer a tool to sell a product. It is the goal itself. Once the marketing succeeds in building a massive online following for a human “brand,” the record company is ready to sell the product. Creativity and originality are as dead as the bat whose brain Ozzy Osbourne crushed with his molars.

Vox surveyed the dry and decaying cultural landscape, and concluded, “Everyone’s a sellout now,” advising readers that if they want success in a “creative field,” they have no choice but to rise through the ranks on Tik Tok. Imagine Joni Mitchell posting videos about her shoe collection and skin care routine in the 1970s or Herbie Hancock sharing a “sponsored” reel for Versace, and you can begin to estimate the damages to artistic independence and integrity – and flat out fun – that our society is currently inflicting on itself.

Even though I was already an admirer of Black Sabbath, I reacted like my nephew when an older friend told me about when he saw the inventors of heavy metal for the first time. He had never even heard of Black Sabbath. They were on their first American tour, opening for some inferior band at the Auditorium Theatre. “The lights went out, the whole place was dark,” my friend said, “Then we heard the crushing opening chord to ‘Black Sabbath,’ the lights started flashing like in some crazy movie, and then Ozzy came out in a black jacket and hood, crouched low, looking like a vampire.”

As a guitarist who toughed it out in rock bands his entire life, the introduction to Black Sabbath was a defining moment in his musical formation. On the simpler level of human experience, he said, “I felt excited and scared at the same time.”

A cliched phrase is “fear of the unknown.” It describes a natural instinct that humans have developed for survival. Black Sabbath’s music was not only scary because of the deliberately spooky aesthetics and lyrics that Ozzy, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward built around it, but also because it was unknown. The invention of a new art form unnerved the audience. Black Sabbath rebelled against the protocol and parameters of their time, and in doing so, became timeless.

Their first four records constitute one of the greatest runs in the history of rock music, standing alongside any single artist or band in terms of musicianship, originality, and depth. While Ozzy’s antics, such as the aforementioned bat incident, might have become as recognizable as the music itself, his songs were not only musically groundbreaking, but also lyrically brilliant. Critics have a tendency to overlook or dismiss lyrical substance from bands that play heavy music. Black Sabbath was the Edgar Allan Poe of rock and roll, alchemizing the macabre into an inspection of the core elements of life. Their expression of dark passions and questions explored the deepest subject matter, such as mortality, the influence of death on life, and questions of justice.

“War Pigs” is a strong candidate for the greatest anti-war song ever written. Ozzy Osbourne explained that the “flower children” writing protest songs against the Vietnam War wrote only light material, fodder for sing-a-longs. Black Sabbath aimed to write a song that captured the sound of evil itself. The original title was “Walpurgis,” meaning the witches’ sabbath. “Walpurgis is like Christmas for Satanists,” bassist and co-writer Geezer Butler said, “And to me, war was the big Satan.”

“War Pigs” is one example of something that is increasingly rare in popular music: artistry. “Children of the Grave,” “Sweet Leaf,” “Supernaut,” “Hole in the Sky,” and so many other songs capture a group of musicians who mastered a craft, and fused their mastery with a desire to say something relevant about human life and the state of the world. Crucial to these songs were the songwriting contributions and vocals stylings of Osbounre. His voice was unique and forceful, and it certainly helped that he could make it sound as creepy as a snake slithering down a dark alley.

The music created a genre, inspiring all the musicians that played Ozzy Osbourne’s massive farewell show on July 5th: Metallica, Slayer, Alice in Chains, Steven Tyler, and on an on. It also made its mark in surprising centers of musical architecture. Jazz Sabbath, a collective of jazz musicians led by pianist, Adam Wakeman, has released three great tribute records to their namesake.

Larkin Poe, a sister blues-folk duo, credit Ozzy Osbourne as a major vocal influence, “an old-time singer.”

Ozzy’s solo music never reached the heights of Black Sabbath, but songs like “No More Tears,” “Mama, I’m Coming Home,” and of course, “Crazy Train,” demonstrate that he was more than capable of creating powerful music without the other members of Sabbath.

None of this is to say that Ozzy Osbourne did not become a “brand” himself. The reality television show that aired on MTV, the TV commercials in which he appeared, and even his touring music festival, Ozzfest, all reaped the pecuniary benefits of his frightening-turned-lovable image. What distinguishes Ozzy from the boring and unimaginative pop stars of the algorithm is that it was an image he created. And when he created that image, he was often battling against record company executives, promotors, and PR stiffs. Finally, it was an image he created in congruence with his music, in order to sell his music. He wasn’t a mere image with songs in the background. No “rock star whisperer” was going to tame Ozzy Osbourne.

The death of Ozzy Osbourne is most heartbreaking for those who knew and loved him. It is also sad for anyone who cares about cultural vibrancy and musical artistry. Ozzy Osbourne was one of the last rebels who made it on a grand level – selling out arenas and stadiums, rising to the top of the charts. Anyone honest would have to acknowledge that it is impossible to imagine the rise of anyone like Ozzy in the contemporary “marketplace,” which more than anything is what it sounds like – a zone where commerce has finally won its ancient fight with art.

The Prince of Darkness leaves his Earthly home when the United States is regressing into an increasingly repressive and religious home of Satanic Panic paranoiacs. In 2023, Sam Smith and Kim Petras performed their pop duet, “Unholy,” dressed as devilish ministers, surrounded by fire and backup singers whose outfits borrowed heavily from the horror movie, The Ring. Republican officials, such as Senator Ted Cruz, whined that it was “devil worship,” while right wing podcast buffoons claimed that it was part of a conspiracy to lead children to Satanism. Have these people ever heard of Ozzy Osbourne? What will they do when they find out that he actually sang, “Would you like to see the Pope on the end of a rope?” and “My name is Lucifer, please take my hand”?

In Paradise Lost, John Milton famously writes Lucifer as declaring, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

Because of his Luciferian rebellion, fighting for freedom, personal expression, and self-earned artistry, Ozzy Osbourne reigned on Earth. Contemporary celebrities know only how to serve. This isn’t exactly heaven.

David Masciotra is the author of six books, including Exurbia Now: The Battleground of American Democracy and I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters. He has written for the Progressive, New Republic, Liberties, and many other publications about politics, literature, and music. He and his wife live in Indiana, where he teaches at Indiana University Northwest.

The post Better to Reign in Art Than Serve the Algorithm: Ozzy Osbourne as One of the Last Rebels appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.