Not all ultra-processed foods are unhealthy, according to the American Heart Association, which calls for a nuanced categorisation of these products.

With the conversation around ultra-processed foods (UPFs) dialled up to eleven in the US, and now, the American Heart Association (AHA) is weighing in on the debate.

In a new scientific advisory published in the Circulation journal, the non-profit reviews current research around UPFs to outline opportunities for policy reform and improve public health in the country.

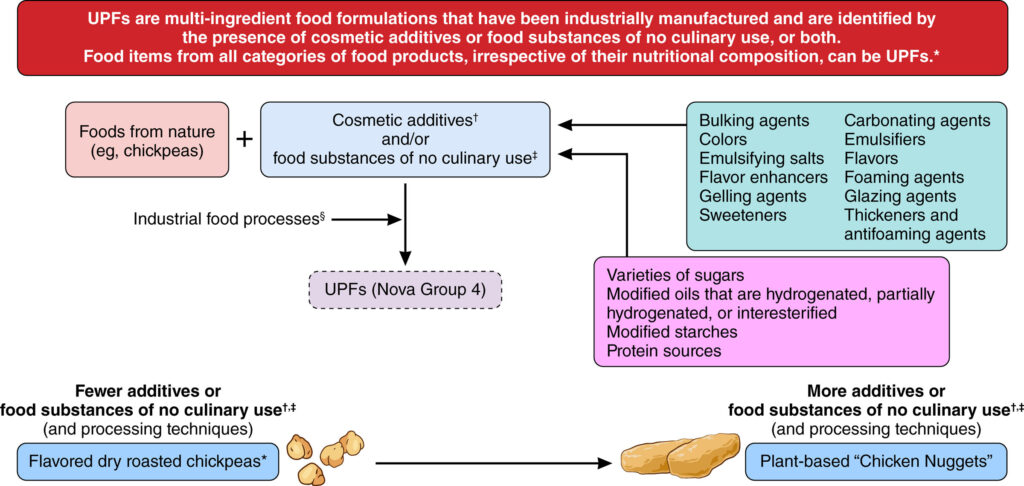

More than half (55%) of American calories come from UPFs, with children and teens overindexing on their consumption. These products, as defined by the Nova classification back in 2009, comprise industrial formulations and techniques like extrusion or pre-frying, and cosmetic additives and substances deemed to be of little culinary use.

Most of these UPFs, the AHA suggests, are unhealthy for us – but not all of them. “Certain whole grain breads, low-sugar yoghurts, tomato sauces, and nut- or bean-based spreads are of better diet quality, have been associated with improved health outcomes, and are affordable, allowing possible inclusion in diets,” the advisory reads.

The statement reinforces the thoughts of many nutritional experts, who have warned that the level of processing doesn’t directly define how nutritious or healthy a food is. This has led to calls for an overhaul of the Nova classification, which the AHA indicates support for. “The categorisation does not include a breakdown of the nutritional quality of the foods,” the paper states.

“The relationship between UPFs and health is complex and multifaceted,” said Maya K Vadiveloo, chair of the writing group for this advisory. “We know that eating foods with too much saturated fat, added sugars, and salt is unhealthy.”

She added: “What we don’t know is if certain ingredients or processing techniques make a food unhealthy above and beyond their poor nutritional composition. And if certain additives and processing steps used to make healthier food like commercial whole grain breads have any health impact.”

The research comes on the heels of the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) move to develop a definition of UPFs, and a citizen petition by the agency’s former commissioner, David Kessler, asking it to revoke the food safety status of processed refined carbohydrates. The latter provides a pathway for the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement to regulate UPFs, but also challenges the Trump administration to take action.

Food processing has both risks and benefits

The team of scientific advisors have reinforced the AHA’s dietary guidelines to reduce the intake of most UPFs, especially those high in salt, saturated fat, and added sugars, and replace them with healthier options like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts, seeds and lean proteins.

This determination is based on research linking certain ingredients used in UPFs to a number of health risks, including cardiovascular disease and early death. However, the AHA notes that not all industrially processed foods are UPFs, and some methods of processing can extend shelf life, reduce costs, preserve nutritional, functional, and sensory qualities, and boost food safety.

“Some techniques also enhance year-round food availability and convenience and may even reduce harmful compound formation,” the review states. “Additional advantages include the use of antioxidants to prevent spoilage and nutrient fortification, such as folic acid, to address dietary inadequacies.”

It continues: “Processing can enhance convenience, and in the context of time constraints and reduced home cooking, moderate use of a small number of nutrient-dense UPFs may support healthier dietary patterns. This can also reduce the domestic labour burden – historically shouldered by women – aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of promoting sex equity.”

The AHA suggests that the modest use of such UPFs “may help offset other costs associated with adopting healthier diets”. “A small number of UPF products, such as certain commercial whole-grain, low-fat dairy, and some plant-based items, may contribute positively to healthy dietary patterns,” it says.

“Whole-wheat breads and unsweetened soy milk with emulsifiers can support nutrition security in low-income and low-access communities by offering convenient, affordable, and palatable options,” it adds. “This underscores the need for more nuanced subcategorisation and mechanistic understanding, rather than blanket recommendations to restrict all UPFs.”

Food processing has become a bone of contention among nutritionists and health experts across the world. For some, UPFs are the biggest issue with the current food system, but others echo the AHA in calling for a more nuanced approach.

“The lack of consensus continues to impede research and policy development. Establishing agreement could advance our understanding of how different UPF subgroups and degrees of processing, such as the type of additives, affect health,” the AHA’s advisory writes.

Nova classification not enough for UPF policymaking

The paper argues that developing nutrition policy solely based on the Nova classification is challenging, since “some nutrient-dense foods with UPF characteristics may be neutral or even beneficial to health”.

This is especially pertinent for the US. Implementing Nova-based guidelines may be easier in countries where UPFs comprise a small part of the diet. But here, the AHA bats for a “phased regulatory approach” that initially distinguishes UPFs by nutritional quality, then targets products high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) and with specific cosmetic additives.

“The focus should be on cutting back the most harmful UPFs that are already high in unhealthy fats, added sugars, and salt, while allowing a small number of select, affordable UPFs of better diet quality to be consumed as part of a healthy dietary pattern,” it says.

It outlines several research and policy changes to better reflect the impact of UPFs on human health. Policymakers should introduce approaches for individuals, food manufacturers and retailers to shift eating patterns away from HFSS foods and towards healthier UPFs.

These products could include whole plant foods, non-tropical liquid plant-based oils, seafood, dairy low in sugar and fat, as well as canned beans, whole-grain breads, and non-HFSS vegan meat and dairy alternatives. This aligns with the AHA’s heart-healthy certification of some Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods products.

Stakeholders should also enact multi-pronged policy and systems-change strategies (like front-of-pack labels and taxation on HFSS foods), while the FDA’s ongoing efforts to modernise its food additive science should be enhanced.

The AHA also calls for increased research funding to explore critical questions about UPFs, including whether it is the extent of processing that makes a UPF unhealthy, or the fact that it contains unhealthy ingredients. Another key target of research should revolve around sustainability, determining the environmental impact of plant-based and overall UPFs, and the effect of processing on food waste and security.

Two in five Americans think all UPFs are unhealthy, an incorrect belief according to the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), which commissioned the survey last month. “We are pleased to see the AHA point out that there are healthful and unhealthful UPFs,” said Noah Praamsma, PCRM’s nutrition education coordinator. “There are actually many healthful UPFs that reduce risk of disease and tend to have one thing in common: they are derived from plants.”

The post American Heart Association: Some UPFs Are Healthy & Need A Nuanced Approach appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.