What does your studio look like right now?

My studio is in a building that was built in 1914 as a Ford garage, and then it was renovated into a microbrewery in the ’90s. It’s 5,000 square feet of space and if you would enter in through the sliding doors, through the back, you’d come into the area that I work in mostly. There is this series of large movable walls and I’d say I have about five works in process in my studio right now.

What does your studio look like when you’re doing your best work?

I find that times when I’m struggling the most in my work are when my studio is the cleanest and most organized. It seems almost antithetical to the conditions that I think are, in some ways, the best for working, as in, my spaces are clean and walls are empty. I do keep a sort of normal routine in the studio every day that I arrive. In the morning, I get up pretty early and I clean off this large table that I have. I usually leave it as a mess and then the first thing I do is clean that off so that it’s fresh. Then I’ll write a little bit, like three lines is what I’ve tasked myself with. That’s when the day starts. Even if I have something on the table that I am in process with, I’ll still clear it off so that there is that brief moment at the beginning of the day when there is no clear agenda and I can go in any direction that I please.

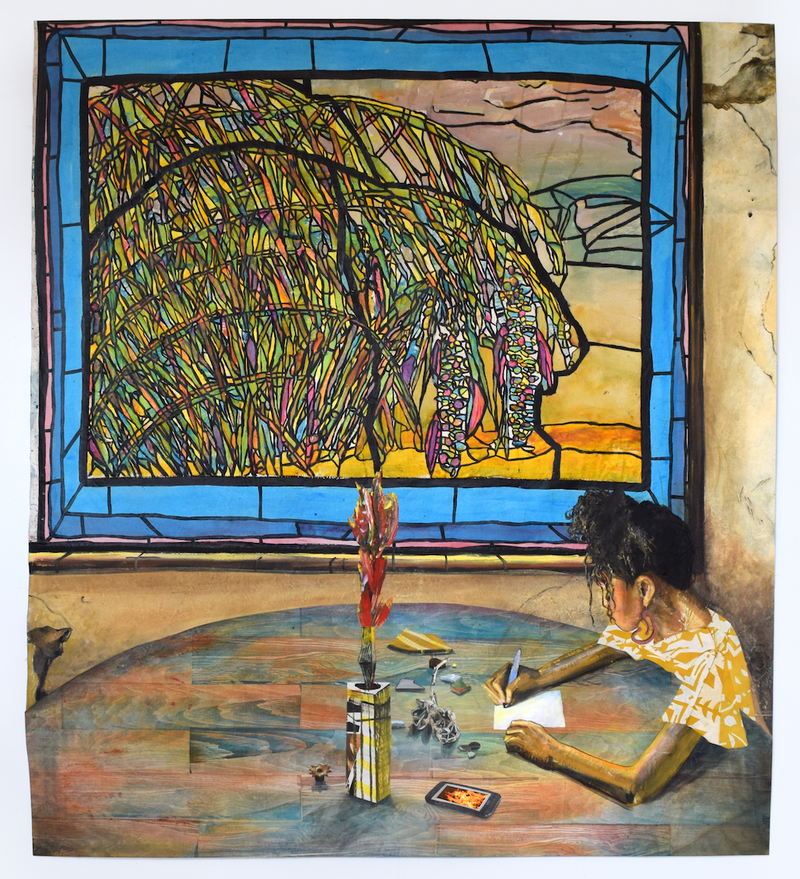

Light It Up, 2019. Acrylic, printing ink (monotype, woodblock, lithograph), and oil on muslin and canvas with video insert. 69 1/4 x 61 ¾ inches. Courtesy of the artist.

I can imagine the ways in which having a less than tidy studio could lend itself to making your work, which includes many different materials and processes often happening in one singular piece. Have you always embraced multiplicity?

I think I’ve always embraced it, but I can remember one of the first artist lectures I gave at the University of Wisconsin, I think it was 2008. This is pretty early on in my artistic career and a student asked me, “Well, are you okay with how many different directions your work is going?” When I received that question was almost when I was able to see that that was true of myself. I did have kind of a moment of panic, like, “Is this bad? Is this going to hurt me in some way?” I have had dealers tell me, “Oh, I wish you were still doing that thing that I was really excited about.” Perhaps moving out to Carrizozo [New Mexico] was an attempt to quiet those voices. It’s definitely a situation from which I no longer question in myself.

Studio view, 2019. Photo by Angie Rizzo.

Your approach resonates with me, though there are times I have fantasized that I would “have it all figured out” if I chose one thing.

As an artist, I used to think that there would be a moment in which I would figure it out—figure out what my work was about, figure out what I set to task towards every day—but it’s never that way. It’s much more the spiral logo from the [The Creative Independent’s] website, in that we return back to the same doubts continually, yet there’s always a new vantage point from which we’re spiraling in a certain direction.

Reflected, 2020. Oil, acrylic, woodblock print, digital print, lithographic print on muslin and canvas. 50 x 71 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

When doubts and insecurities come up, how do you work with them or move through them?

Well, I turned 45 recently, and one thing that’s good about being 45 is that I can see that the insecurities and the stresses are just part of the process and that they come and go, as well as the intense, beautiful, creative sparks and confidence and feeling of connection. You can’t will one away and still have a vibrant creative practice, in my opinion, though there are cloudy distractions of the mind that can actually stop me from putting pen to paper. These distractions can be doubts turning in to distractions. Recently I’ve found a lot more success being able to stop and give that doubt my attention, and it just dissipates immediately when you turn towards it.

I was first thinking about this question in relation to some of the fine details and themes of your work, though now I’m thinking in the broader sense, after what you said about giving your doubt some attention. How has your attention changed over time?

I love that question because [the awareness of] where we turn our attention is an awareness of the Trump era for me, in wanting to turn away, and at the same time feeling like I can’t stop looking. It made me really want to be intentional about my attention. Attention is different from willing oneself to be oriented towards a certain thought. Attention is continually arising. Recently I’ve been realizing that the process of making is not this linear stream of idea to fruition, but actually a conversation with whatever strange creative creation appears before me. The work, the attention, is actually more like a conversation. I think one of the things that’s so great about being an artist is that I get to see this thing that I make that does feel outside of myself in a lot of ways. It also feels as if it is linked to a larger well of creative energy and inspiration that is actually more of a connective tissue that all artists share. There’s this kind of looking back-ness in the work that I’m really giving more due to. More and more, especially within the pandemic, I’m interested in how incredible the experience of looking at artwork is, because there is a limited access to that experience. I want that reflection in the details and the attention. I want the artwork to reward that looking to be engaged and to have discoveries therein, if you give it your attention.

Installation view, Spread Wild: Pleasures of the Yucca. Smack Mellon, 2018. Photo by Etienne Frossard.

A subtle but powerful detail in one of your recent shows was a faux drop shadow painted directly on the wall under the frames of the paintings.

The drop shadow, to me, is like the painting itself is self-aware and in on its own making, or it’s not trying to pretend to be something that it’s not. The frame itself is also kind of a faux frame and the fact that everything is extremely flat draws our attention to things that we might overlook. The life force of a thing can be completely created by its shadow.

In addition to those kinds of intimate details and smaller scale, you also work incredibly large. Will you talk about the scale shifts in your work?

I think that I lean towards the monumental scale. I think there’s a desire in that to be seen, to be acknowledged. I also love just one to one scale. I gravitate towards that because when things get scaled down, then there’s more of a sense of trickery or representational shifts that seem in some ways more aligned with a certain kind of Western trajectory of art history that I’m interested in turning on its head, or at least not holding as the master narrative of art. I do love to have things that are small and intimate. I think that there’s a desire for me to put everything into a piece and sometimes when the scale is large, there’s just an ability to really tell a complex, never-ending story. I love how scale shifts in exhibitions alter the viewer on departure from the show. When you have an environment that’s challenging the way you think about scale and space, and then you enter into the street, I feel that that lingers with you in a way that can have a more lasting effect on how you orient yourself to your waking life. In terms of the scale of the work and living in New Mexico and the openness of landscapes here—there’s something about time being a part of the way we think, and the way space affects us. A lot of my pieces will have elements that are collaged or integrated that I made years ago, so there’s this convergence of time and space in the work.

Installation view: Spread Wild: Pleasures of the Yucca. Smack Mellon, 2018. Photo by Etienne Frossard.

What are some of your greatest references or inspirations outside of fellow visual artists?

Immediately I think of writers. There’s this text by Audre Lorde, Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power, and there’s a recording of her giving that talk on YouTube. I return to that. It’s a gem of an essay. I think there’s a lot in this moment for me where I know what I don’t want, but I don’t necessarily know how to actualize the things that I do want. That essay opens doors of future envisioning to me in a way that’s so sustaining. Then another similar one is this [James] Baldwin talk, The Moral Responsibility of The Artist. That’s another way to get out of ruts or get out of moments of doubt or stress, to return to play these things in my studio. So, those two and spending a lot of time outdoors, taking advantage of that in New Mexico.

What are you currently learning?

I’m learning how to privilege the relationships that matter most to me, and have organized and been organized in multiple Zoom interactions with people that I feel hold deep wisdom. My friend Ebony Y. Rhodes is somebody who comes up. She’s a philosopher, and wrote this amazing text called The Geoveritas. This is an unpublished work that we’ve been meeting monthly to talk about and I have been deeply influenced by this relationship with a living philosopher and her text, and just really diving into this wisdom that that holds.

Creatures of the Fire, 2020. Relief print, wood block print, monotype, acrylic, oil, on muslin and canvas. 64 x 57 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

What has making your work taught you about yourself?

It’s hard for me to answer that in a way, because my life and art are really intertwined. One thing that I think art making has really helped me go towards is my relationship to the landscape. I hesitated to depict the New Mexico landscape because it just felt like I wasn’t actually connected to the place, and I didn’t want to default into some sort of manifest destiny depiction of the landscape. Through some art projects, I feel like I’ve really connected to the plants, animals, and insects of New Mexico, and been able to claim an identity as a naturalist, and somebody who really has a desire to turn our attention to the overlooked wonders of the land around us. I feel that a lot of Black artists hesitate to identify within the environmental movements, or to identify as a naturalist because of the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow and being systematically excluded from environmental movements. [I’m thinking of] Christian Cooper out there birdwatching. To open that world up in my art, has really turned my attention towards the beautiful life force that nature provides.

I knew [that I was an artist] when I went to this art camp, Interlochen, when I was a preteen. I wanted to go for theater, but all the theater classes were taken, so my mom suggested I take an art class. It’s almost like my mom knew better than I did what my focus was. I met my friend Martha Friedman there and met these other young artists. I was like, “These are the people I want to be around,” for one, and I realized in making art that I could spend endless time making it. I was never tired of it. When I came back from that camp, I knew that was my future.

Paula Wilson Recommends:

Album: Where the Future Unfolds, Damon Locks – Black Monument Ensemble

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA)

Mixing black with ultramarine or phthalo blue and burnt umber.

Listening to Audre Lorde read Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power.

Artist: Jae Jarrell

Listening to James Baldwin’s speech The Moral Responsibility of the Artist.

This post was originally published on The Creative Independent.