Put a line through that name? Stained-glass window seen from outside the library of the Royal College of Music, London. Photo: David Yearsley.

Bach is back, bigger than ever and just in time for the holiday buying season in this 275th year since his death.

The bicenterquasquigenary Bach buzz reached a frenzied fortissimo after last week’s officially sanctioned—not to say sanctified—addition of two keyboard pieces to the Baroque master’s hefty catalog already running well beyond the 1,000 mark.

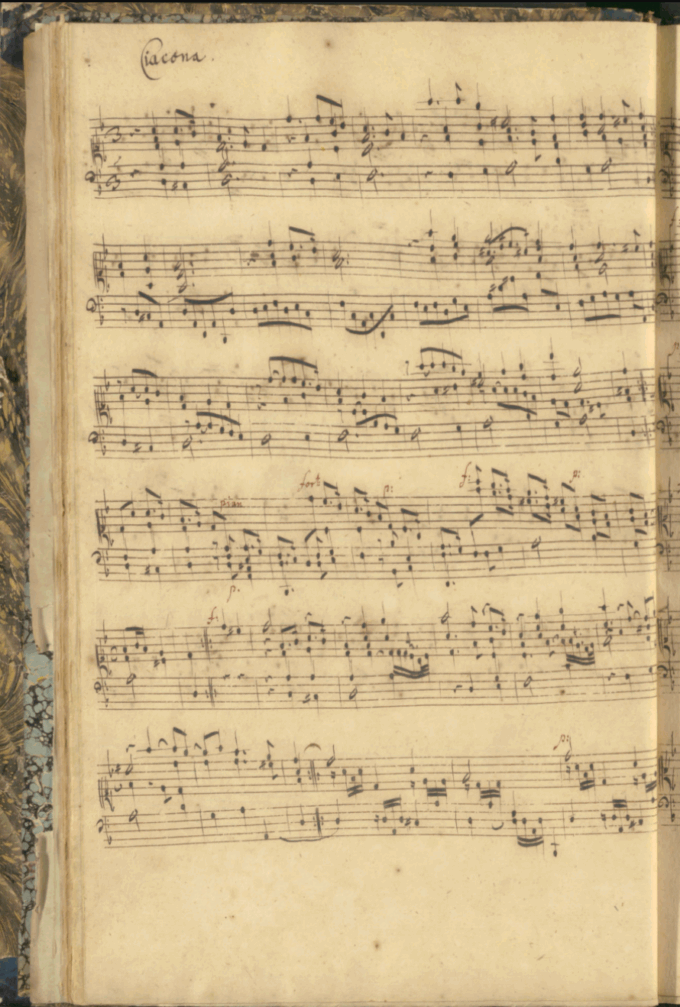

A touch broader than bagatelles but a long way from blockbusters, the works have now been awarded numbers 1178 and 1179 in the BWV (Bach Werke Verzeichnis—Catalog of Bach’s Works). The archival source that uniquely transmits the music can be admired in high-resolution scans accessible through Bach Digital. The news of the “discovery” has been trumpeted and trilled by legions of global media outlets. We should all be thrilled at the rare opportunity to talk so much Bach—and buy more Bach too.

The two freshly ennobled numbers are suave and occasionally swashbuckling organ chaconnes, a well-worn genre in which a repeating bass line of a few bars is elaborated on by the player/composer. Like later jazz musicians, organists before and after Bach improvised such things by the bucketload, occasionally committing their flights of technique and imagination to paper in order to document, refine, and augment their art, but also as a way of providing notated models for their students.

Those learning the craft, the young Bach included, often collected useful examples, copying them from manuscripts circulating among colleagues or lent them—usually for a fee—by their teachers.

Now housed in the Royal Museum of Belgium, the early 18th-century manuscript that contains the two pieces just elevated to Bachian heights begins with a section of such bass-driven works, the title page describing them as Chacconen. (The pieces themselves are given the designation Ciacona (omitting one of the Cs of the more usual Italian spelling, Ciaccona).

Beneath the word “Chacconen,” a later owner of the volume, the north German organist J. J. H. Westphal, wrote out in a hand that is clearly distinct from that of the title itself: “von J. C. Graff und Joh. Pachelbel und andern berühmten alten Componisten und Organisten”—by J. C. Graff and Johann Pachelbel and other famous old composers and organists. Born a half century after the manuscript was copied, Westphal is unlikely to have known who those other organists, if any, might have been. Three of the six Ciaconas do have composer attributions: two to Pachelbel and one to Graff. There is no mention of Bach.

Yet the ascription to him is now being universally accepted. Credit for the (re)discovery has gone to musicologist Peter Wollny, Executive Director of the Bach Archive in Leipzig, though his “team” has also been thanked, as at those trophy-award speeches that come at the end of Grand Slam tennis tournaments. At a formal presentation of the new/old pieces in Leipzig’s St. Thomas Church, the very place where so many of Bach’s cantatas were first heard, German Federal and State Ministers for Culture and Tourism spoke of “a great gift to humanity,” wrapping Wollny’s valiant three-decade quest for holy truth in mythic tones. His find had also rekindled hopes for greater funding in “challenging times” and renewed faith in Germany’s cultural patrimony. Wollny himself has revealed his own “sense of duty”—a musicological crusader’s unquenchable thirst finally slaked at the Bachian grail.

Wollny claims “to be 99.99% sure” of his findings. In particle physics, the standard for certainty is something called 5-sigma, which allows only a 1-in-3.5 trillion chance that the result is a fluke. Even I know that there’s a big difference between muons and manuscripts (although there are gazillions of the former in the latter), yet I can’t help but raise a skeptical eyebrow on behalf of the silent, doubting .01% micro-minority.

It was back in 1992 that Wollny, then a graduate student at Harvard, came across the Brussels manuscript and was struck by the high quality of these two pieces nestled in among supposedly more workmanlike efforts by Pachelbel and Graff. One of Germany’s leading organists around 1700, Pachelbel was a teacher of Bach’s older brother with whom the young Sebastian lived after being orphaned just before he turned ten.

Buttress for Wollny’s initial impression of the anonymous chaconnes (that’s the more usual genre designation, one taken from the French) and his inkling of Bach’s possible authorship came in 2012, when research team member Bernd Koska found a 1727 application for an organist job written by one Salomon Günther John in which he declared that he had studied in the town of Arnstadt, where Bach had held his first post, leaving it in 1707. Another letter of 1716, also written by John, was discovered in 2023. Analysis of these and other handwriting samples confirmed John as the scribe of the chaconnes.

I wouldn’t dare to doubt Wollny’s impressive, confidently brandished forensic skills, but bringing John definitively into Bach’s orbit and establishing him as a copyist of the manuscript doesn’t get me anywhere near 99.99%.

In his remarks that come after those of the politicians, all delivered at the base of the pulpit in St. Thomas Church, Wollny acknowledged the labors of 19th-century Bach devotees who collected and curated the master’s work. But Wollny also criticized these “enthusiastic pioneers” for some of their attributions “based on intuition rather than rigorous analysis that did not always withstand critical scrutiny.”

Like the 19th-century predecessors Wollny criticizes, his attribution of the chaconnes rests on his intuition, clad now in 21st-century certainty and robustly supported by the Bach establishment. Eminent performers like the pianist Angela Hewitt and the conductor-organist Ton Koopman, who scurried through the pieces at the public presentation in Leipzig last week, discerned the unmistakable signs of Bach’s young genius.

The recent Leipzig performance by Koopman was hailed as the first in more than 300 years. Can we please entertain the possibility that previous owners of the manuscript—Westphal and Fétis—were more than simply rabid collectors but also might have eagerly played through their acquisitions for friends or maybe even for strangers, possibly even on big church organs? A modern edition of the Ciacona in D minor prepared by Christian Hesse has been up on IMSLP since 2024, there attributed, apparently agnostically, to either J. C. Graff or J. S. Bach. More accurate would be to call last week’s event in Leipzig the first performance of the chaconnes as works by J. S. Bach—maybe not just in 300 years, but ever.

Whatever the evidence gleaned from archival research, the now-accepted attribution, agreed on by acclamation, relies ultimately on inferences and judgments about the style and quality of the pieces.

The more interesting and impressive of the two is that in D minor, now BWV 1078. The piece brims with confidence, even bravura, proud of its bold flourishes and haughty shifts of register. If one so chooses, one could decide to hear and see in these conceits something of the brash young Bach, already known in Arnstadt for his impudence and temper. Uniquely among the chaconnes in the manuscript, copyist John added red ink to indicate manual changes that yield fun and flashy echoes. A winning innovation comes when the bass line frees itself from the shackles of repetition. The liberated theme then launches a four-part fugue in which all voices participate equally. It’s an idea that Bach ran with (in place at the organ bench) when creating his most colossal chaconne—dubbed instead a passacaglia—in C minor, BWV 582. That mighty work is dated by scholars sometime around 1710, only a few years after John copied out the far more diminutive D-minor essay in the genre.

First page of an anonymous Ciacona now attributed to J. S. Bach. Royal Library of Belgium.

The Ciacona in G minor (BWV 1179) that comes next in the manuscript is more generic, as is particularly evident in a final pair of passes through the bass pattern that trot out some showy but utterly predictable footwork on the organ pedalboard. Herein lies one of the many problems of seeking the singular in works that traffic in trusted clichés. These patterns for improvisation are necessary elements for any student to learn and for working organists to apply as needed: rinse and repeat. These tricks of the trade are pedagogically potent precisely because of their generic qualities. Such practical attitudes to composition and performance are often hard to square with expert commentary that seeks signs of greatness to come, duly finds them, though with the proviso that the youthful genius is not yet fully formed.

If not Bach then who? So goes the standard response to doubting counterarguments like the one I’ve given only an outline of here.

How about good old Georg Böhm, teacher of the teenage Bach? Böhm was a terrific organist of Pachelbel’s generation, practiced in francophone poise, Germanic gravitas, and transalpine fantasia. He hailed from Bach’s native region of Thuringia but held forth for decades on a massive organ in an ancient, echo-rich church up north in the Hanseatic city of Lüneburg, where Bach was his pupil. That student sojourn concluded a couple of years before the young S. G. John turned up to learn from Bach, twenty years old in 1705 and by then back in his clan’s heartland.

Böhm could have handily served up the sallies and swerves of these chaconnes on the organ, then put them on paper and passed them on to Bach, who could have duly added them to his own portfolio.

But a possible ascription to Böhm or a prudent question mark after Bach’s name won’t garner headlines, lure political bigwigs in front of cameras, or bump up the bottom line.

The two just-elected members of the BWV Club could well be by Böhm. They could well be by Bach. He built many Böhmisms into his early works. Or these chaconnes could find Bach collaborating with Böhm or masquerading as him, copying him in every sense. Or they could be by some other B of the Baroque, though I do agree probably not Bachelbel—a common contemporary alternate spelling of Pachelbel. I’m offering even money on a Bach-versus-Böhm wager. Unlike Wollny, I admit that I could be wrong. I welcome that uncertainty, indeed revel in it.

One of the Guardian stories on the “discovery” quoted Wollny’s apparent assertion, perhaps taken somewhat out of context and presumably now regretted by him, that, “If a doctor makes a mistake it’s not such a big deal. But if I make an error, it will sit in books for hundreds of years.”

Bach himself might have had a different view on the relative importance of physicians and forensic musicologists. He was blinded by a quack eye doctor in the last months of his life, and here’s betting (again) that he would rather have opted for a few more days of failing sight than posthumously bask in the limelight reflecting off a couple of pieces that might not even be by him and probably wouldn’t mean much to him if they were.

The post New Bach, Old Doubts appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.