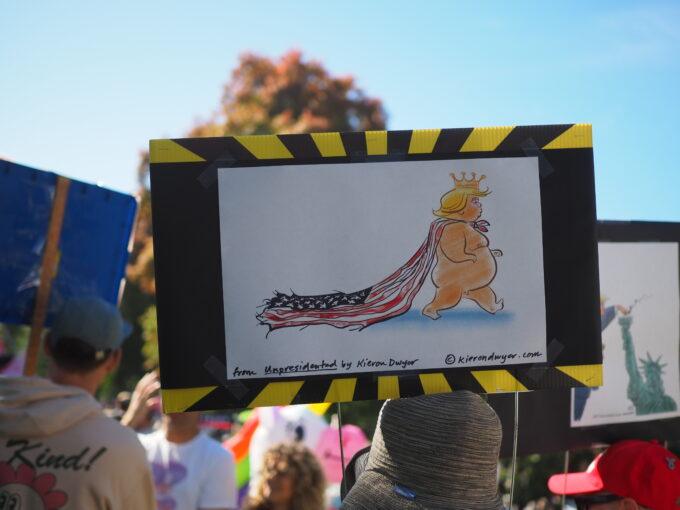

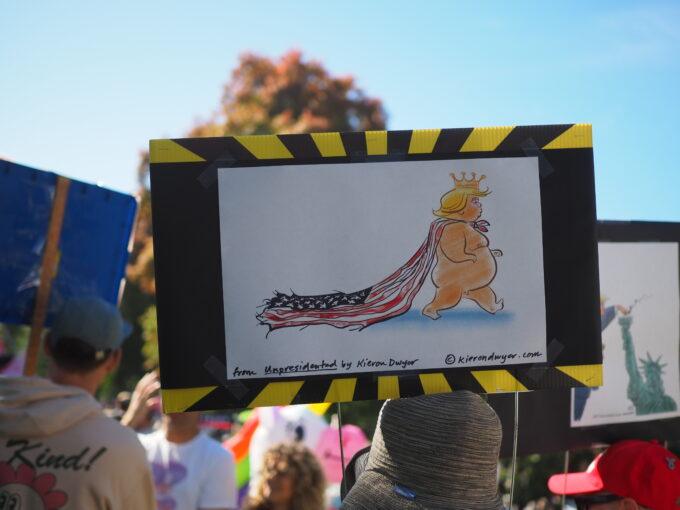

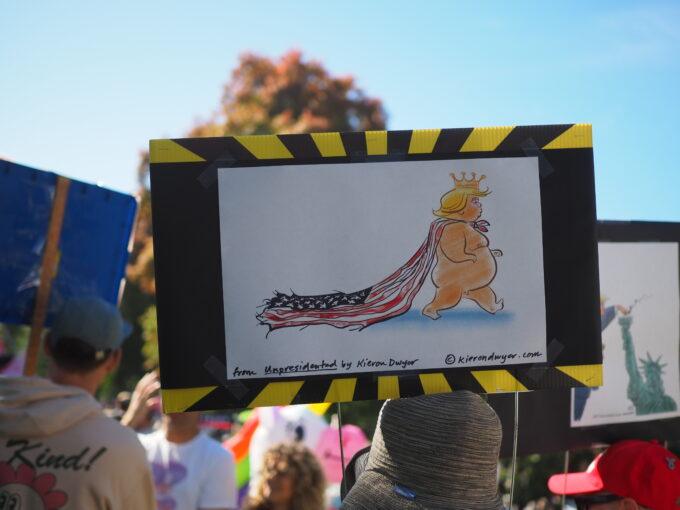

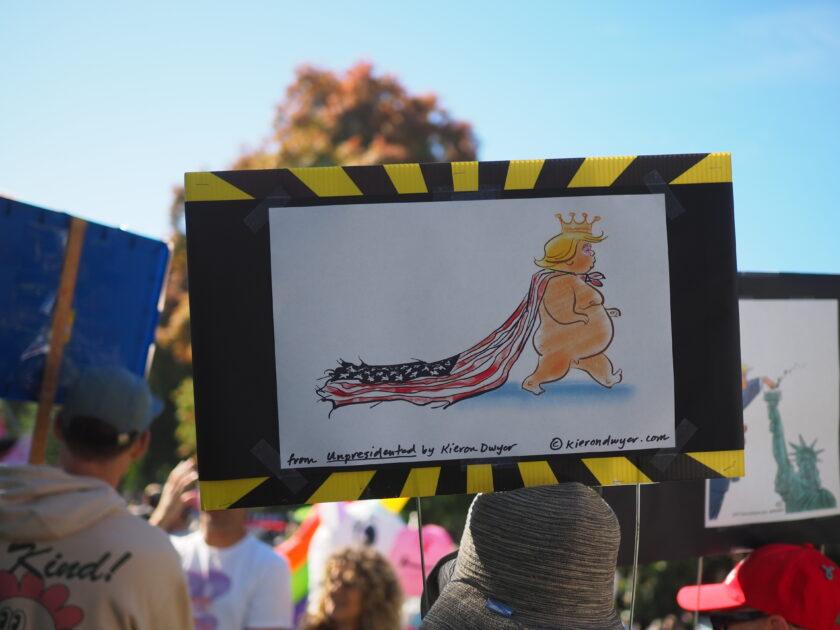

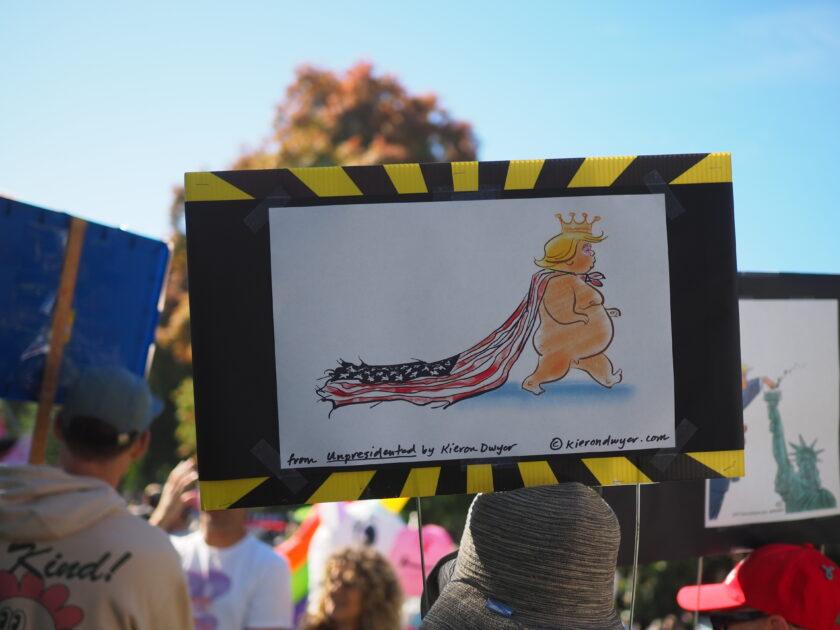

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

I don’t know who came up with The Donroe Doctrine, but I am grateful for that bit of glibness.

Any day now, we seem on the verge of something in Venezuela that may very well savage and ruin the lives of 30 million Venezuelans. The likelihood of that spreading to neighbors in Latin America should be near-certain – if you have doubts, ask the neighbors of Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya…

I was interviewed by Sara Katib of TMJ News Network about the U.S. long-awaited and likely regime change in Venezuela. We also spoke about how Venezuela connects not just to regional US aspirations and policies but also to the larger Trumpian foreign policy.

No Fly Zone As Prelude To War

Sara: The latest updates reveal that Trump has just ordered the entire closure of the Venezuelan airspace, coming maybe a day or two after he said that US strikes on Venezuela could begin very soon. With so much happening right now, many are saying that it’s possible we could be seeing an all-out military offensive. There are so many kind of theories out right now, but understanding the situation requires examining different perspectives.

Matt: There are a lot of different ways to try and understand what’s happening here, and all of them are valid. We can point to different examples of how closures of airspace in the past have signified one thing or the other. You could look at this closure of airspace as potentially being a no-fly zone similar to what the United States and NATO carried out over Libya in 2011. You could look at it as what occurs, say, between Iran and Israel. Before those nations engage in firing missiles at one another, they close the airspace because you don’t want a civilian aircraft to get hit by a missile in the sky. And we’ve seen that happen plenty of times. Of course, that occurred in Iran just a few years ago when the Iranians unfortunately shot down one of their own civilian airliners. As well then, too, you go back to 1988 when the Americans shot down that Iranian civilian airline, right? I mean, so there’s precedent for why this is done. Sometimes, as I just said, it’s because to take precautions to make sure that there’s no civilian aircraft in the sky. Others are to create conditions for the battle space, right?

So if this is more of that, if this is where the Americans are declaring a no-fly zone, essentially, well, this gives them an excuse to shoot down a Venezuelan aircraft, and this also sets up the case for a potential casus belli, a reason for war.

American Imperial Authority

Sara: So far we’ve seen naval deployments and boat strikes, the alleged drug boats that have been said. And these operations we know are being justified through terror designations and counter-drug authority even. And the question that arises here is, does the U.S. even have that authority? Is the U.S. violating international law here or potentially crossing red lines that no one is talking about?

Matt: Right. The United States does not have authority to close Venezuela’s airspace. It certainly doesn’t have the authority to blockade Venezuela as it has through decades of sanctions. It doesn’t have the authority to carry out coup attempts as it has for the last couple of decades against the Venezuelan government. And most especially, it does not have the authority to extrajudicially murder people on the ocean in international waters. So the United States is acting in complete disregard of international order, international laws, international institutions. But you know, this is the way empires will act and that’s what you have here. And in particular when you’re talking about a nation or an empire acting in its own sphere of influence, and that’s how the United States views all of Latin America, Central, South America, the Caribbean, and has viewed it that way throughout the United States’ existence, then, of course, any rules, any laws, any norms that exist that contradict American power are simply disregarded.

The Moral Necessity For The Lies

Sara: One other point that is actually growing among the public as well: many analysts, and now if you were to ask the American public, they would tell you that we know this is really not about drugs. It’s about power. It’s about oil. It’s about politics. And it’s interesting because now if you were to talk to most people because of what they have seen previously with U.S. interference in other countries, most people know that when the U.S. fixates on something like this, there’s definitely more than what meets the eye.

The public narrative in this case differs significantly from the real motives behind U.S. policy here. The storyline that the United States is doing this to protect its citizens from nefarious and evil drug traffickers—you hear this from the president, from Donald Trump, who every time the United States destroys a boat, without any evidence, without any type of information or details as to who was on that boat, let alone what that boat was actually doing, let alone the whole counter to the narrative that these boats if they actually were coming to the United States, would have to be refueled 10 or 12 times because they’re so small, right? I mean, all these different things that belie the narrative.

Well, the storyline, though, the explanation is that we’re protecting American citizens. Each of these boats has enough fentanyl on it to kill 25,000 Americans. That’s what you’ll hear the White House say repeatedly. And these types of stories, these types of narratives are used by governments, you know, around the world and throughout history to justify their actions. And all they want is just for their base, their core supporters to have a rationale, to have an explanation, right? It’s something that people who are outside of that core dismiss. No one believes it. I think anyone watching, most Americans don’t believe it and certainly those around the world, you know, don’t believe it. But that’s not what the government cares about. The government cares about ensuring that its people have some type of moral construct on which to base their actions. Because, if they don’t have that moral construct, right, they don’t have their rationale, their explanation. If you don’t tell U.S. Marines and soldiers that you’re invading Iraq to protect the United States from another 9-11, your invasion is not going to succeed. Your occupation is going to fall apart very quickly. And the same thing has to occur here in Venezuela. So while most of the United States don’t believe this is the case, and almost no one around the world believes this story of Venezuela trafficking drugs, killing tens and tens of thousands of Americans because of it, it doesn’t matter to the White House. It doesn’t matter to the Pentagon or the State Department. What matters is that the people who are carrying out these policies have some type of moral construct, have some type of narrative on which to fall back on so they won’t doubt what they’re doing. That’s essentially what’s occurring here.

Libya Redux

Sara: Some people are arguing that certain factions in Washington are obviously seeing Venezuela as a geopolitical opportunity. But we also know that often like top politicians, for example, they’ll do all the tough talk, they’ll do all the war talk, but you’ll have sometimes the Pentagon will kind of quietly try to avoid another long term conflict. From experience examining these situations, there are signs about whether the Pentagon might actually be reluctant about getting involved in Venezuela or whether they’re also as equally invested in this whole plan.

Matt: Well, I think you have senior leaders in the Pentagon like the Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, who like the imagery, who like the optics of destroying boats on the open water with Hellfire missiles launched from drones. It’s part of their tough guy machismo persona that they want to, that they want not just want to present, but they actually believe in themselves. I think within the Pentagon, you have a reluctance to engage in any kind of warfare that is not winnable. So the idea of this being another Iraq or an Afghanistan where the United States is going to put large amounts of ground forces and occupy the country, I don’t think that’s even being considered. And by the way, by the nature of the forces that are in the region, even though there has been a large naval buildup…there continues to be more aircraft being assigned to the region. I think there’s about 20,000 or maybe 25,000 troops in and around Venezuela at this point, not nearly enough to conduct an invasion. So I think what the Pentagon is looking for in terms of a strategy is something much more akin to what you saw carried out in Libya, where the United States would provide airstrikes. There would be CIA and special operations forces on the ground. But the bulk of the ground force, the main effort would come from Venezuelan opposition figures, Venezuelan opposition groups. And the idea being that the United States would provide airstrikes, they provide special operations forces, cyber attacks, what have you, but that the Venezuela opposition would be the ones who would pull the government down and rebuild a new one. And, we can all look back and just consider how well that actually happened in places like Libya, or say in Syria, and other proxy wars.

Setting Fire To All Of Latin America

Sara: When examining Iraq and Afghanistan, there are obviously valuable parallels to consider with the current situation. From the inside perspective of how U.S. interventions unfold, especially in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan, and obviously, the whole regime change thing as well is another theme that we’ve seen the U.S. push forth with many countries, backing opposition leaders. One example that bears examination is Iran as well, where for the longest time you’ve had America really pushing for regime change every time, you know, even political upheaval happens in the country and it kind of fails each time. And you then have, you know, a lot of warmongers within the U.S. government as well that are pushing and saying, hey regime change hasn’t worked. Let’s get militarily involved. Let’s actually declare full on war.

Matt: Well, certainly there are all those examples, right? We’ve discussed this idea of we’re going to overthrow Saddam Hussein and we’re going to bring in Ahmed Chalabi and that that opposition is going to stand up a government in Iraq and et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. You know, and you see that with the names that we have, Edmundo Gonzalez, you have Maria Machado, you have a number of opposition figures that have been triumphed and celebrated by the US for two decades now. Juan Guaido, of course, was the man who supposedly was president for a number of years in the first Trump administration…the Biden administration quietly dropped him. So you’ve seen these parallels before. I think one of the dangers in all this, I think people can understand very readily how this would affect Venezuela, the loss of the government, the collapse of any type of authority, and then that vacuum being filled by a whole host of various actors, both Venezuelan and foreign. I think people understand how that could play out and what that would look like.

I think another issue here that doesn’t get talked about too much is how this would affect the entire region. And certainly, I think if you look at Afghanistan, you look at Iraq, you look at Vietnam, those wars weren’t confined to those borders. The chaos, the madness, the instability of those wars spread. So the effects the Afghan war had, say, on Pakistan, the effects the Iraq war had throughout the region, but say, especially in Syria. You know, Vietnam, of course, you look at Laos and Cambodia and anyone who thinks that an American regime change operation, an American war in Venezuela, would be confined to the boundaries of Venezuela, is just not familiar with all the evidence and experience of past examples. And so you could see this spreading of instability, of volatility, of coup attempts, of right-wing aggression throughout Central and South America.

And we’ve heard this already from American officials that Venezuela will be the first, just as 20 years ago, 22 years ago in Iraq, American officials were saying: “after we finish here in Iraq, we need to decide whether we go right or left.” Meaning, are we going to do Iran after Iraq or Syria after Iraq, right? I mean, that’s things that George W. Bush administration officials said outright. You hear similar things from the Trump administration or from their backers that Venezuela would be the first.

You hear this from people in the region as well. Maria Machado, a key opposition figure in Venezuela, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, has said that once the United States liberates Venezuela, then it will go on and liberate Nicaragua and then we’ll go on and liberate Cuba, et cetera. You see right wing groups and individuals throughout Latin America watching this unfold. And then you can imagine that they are speculating how this could be used to their advantage. So if you’re a right wing group trying to gain power in Brazil, in Colombia, in El Salvador [Honduras], you may say that the best way for us to move forward is to engage aggressively, to act out very violently. And only then the Americans will come in and support us, right?. And then, of course, you see the right wing governments throughout South America, whether it being in Argentina, whether it be in Ecuador. You know, certainly you have a right wing candidate who’s likely to win in Chile. I mean, so you can then imagine to the Trump administration using its right wing allies throughout Central America…Honduras, looking at elections this weekend as well there. So you have this possibility then of having a right-wing alliance in Latin America doing Washington’s bidding.

So, the idea that this is going to be confined to Venezuela, I wouldn’t put much on that. I would think that one of the key things to be concerned about here, of course, besides the fate of 30 million Venezuelans, is what’s going to happen to Latin America in general if the United States decides to carry out a regime change in Venezuela.

Why Venezuela?

Sara: This is a critical point right now as well, talking about the bigger picture behind what this could actually mean for the region. Does this administration currently actually understand the scale of what they’re talking about, this idea of getting fully involved, getting militarily involved? Or are policymakers again repeating the same mistakes, the same miscalculations that they’ve done with previous situations?

Matt: I think there’s a mix of both. I think you have those in administration who understand the past examples. Certainly, this is why you don’t see an option to fully invade Venezuela being presented. You know, there’s not enough troops have been committed to provide for an invasion and an occupation. So I think you have that understanding that there are very real political costs to American administrations for overseas wars that directly involve American soldiers. Now, if you could hide those costs, if you can carry out these wars through proxies, then by all means, you can go forward with them. And so I think that’s what animates, that’s what informs this White House, this administration’s thinking on this. You have many who are part of various cliques for a multitude of reasons who have long desired Venezuela. First and foremost is the oil, right? The world’s largest oil reserves. We don’t have to elaborate on that any more than that, right? That’s there. You have had those who are coming from a neoconservative background who view American dominance throughout the world, but especially in our spheres of influence of being paramount, of being the primary effort of American foreign policy. And so as you’ve seen China make inroads in Latin America in the last couple of decades to the point now that China is the major trading partner for a number of Latin American countries, and will be for more as time goes by, this idea of trying to kick China out of our sphere of influence, it has to begin someplace, as well as that ties into a larger imperial worldview, this idea that the United States cannot accept any affront, cannot have any type of country, particularly, again, in its sphere of influence that’s thumbing its nose at the American empire. You can’t allow for any independence or autonomy. [Let alone socialism!]

And so something like Venezuela has been an irritant for decades now for that type of American imperial worldview or understanding. Of course you have people like Marco Rubio who just have an obsession with Venezuela, have an obsession in general with Latin America. But there are those who have an obsession with this government in Venezuela and its predecessor under Hugo Chavez that gets into personal Cold War era mentalities and beliefs. So there’s a number of things that coincide here that allow for Venezuela to be considered to be the right choice for this administration’s first real conduct of war-making or regime change.

Because there’s been no shortage of places that the United States has, under the Trump administration in the last 10 months, have threatened, right? Have advanced their ideas upon, right? We could talk about Greenland, we could talk about Panama, Canada even, right? I mean, as well as other parts of the world. But this is where you see that Venezuela ticks off the boxes in terms of meeting the needs, the wants, desires of so many constituencies, not just in the Trump administration, but throughout Washington, D.C., throughout the American foreign policy establishment and throughout the entirety of the empire.

Reckoning With The Multipolar World And Trying To Explain Israel

Sara: Bringing this conversation back to America, one thing that—and this is a debate because lots of people say it’s not the case—but one thing many are saying, the Trump base is starting to increasingly want is this idea of prioritizing American interests, America first, fortress America, all these kind of phrases that we hear from a lot of people. And this topic has come up frequently with Israel, especially with the idea of the U.S., you know, people calling for Trump and the U.S. to stop their unconditional support for Israel because of everything that they’ve seen. And for many, even if it’s not about human rights and the genocide that’s happening there, it’s about let’s prioritize Americans. We already have so much homelessness back home, so many issues that we’re not addressing, but we are prioritizing Israel. In many ways with Venezuela as well, this conversation has come up about why does America, especially Trump and Trumpers who you would assume would hail this kind of a decision, but they’re kind of stepping back and saying why are we continuously getting involved abroad and not prioritizing Americans home? Is this sentiment growing enough to a point where it’s involved in Trump’s decision making about these issues? Or is this whole imperial theme that we’re talking about right now and getting involved in other countries—and as mentioned, there’s lots of interest on the line for America here—how do these two kind of realities work with each other in this picture?

Matt: Well, I think if you look at who Trump brought into office with him, with the exception of J.D. Vance, not many of his senior people embrace this idea of America first, right? Most of them were neoconservatives or they have orthodox foreign policy views. They are tied to the understanding that is expressed in the George H.W. Bush administration at the end of the Cold War that the United States is the world’s sole superpower. We are the hegemon, and that anything that poses a threat, that even just poses competition to that status, has to be destroyed. And that’s the worldview, that’s the defining foundation, if you will, for American presidents and their administration, up to and including the Trump administration, is that Trump views things differently. And so while his predecessors view the idea that Trump’s predecessors, whether it be a Biden, an Obama, a Bush, there’s no way they were going to give up on this idea of America as a sole superpower.

And you go back and look at their decisions and you see how overextended America becomes because America has to be everywhere at all times confronting everybody. And I think the Trump administration—and this doesn’t hold 100 percent and there are various aspects to it that are disrupted by things such as Israel, by things such as Nigeria, by things such as the fact that the United States now owns part of Armenia, right? You know, I mean, like there’s all parts of this that don’t fit with the overall construct or worldview that the Trump administration has of how the American empire should operate in a multipolar world. But I think the important thing is that Trump administration does view this as a multipolar world. And they have no interest in being in this multipolar world and being one among many. They certainly want to dominate the multipolar world, but they understand that this is how it exists. And so while his predecessors seemingly refused to acknowledge that the multipolar world was already here, still hung onto the belief of America as a sole superpower, Trump doesn’t see it that way. And many of his people don’t see it that way.

And so when you look at it that way, you can understand how you can make arguments then that have an America first flavor to them, right? So you can make an argument that Venezuela is about America first because it’s about the drugs. It’s about becoming energy independent. If we have Venezuela’s resources, we don’t need to be involved in the Middle East. We don’t need to be involved in a war between Ukraine and Russia. If we have South America’s mineral resources, if we kick the Chinese out of Latin America, then we don’t have to worry so much about being in direct competition with the Chinese because we have our sphere of influence here from which we can extract so much. And I think that is somehow how there is a method to the madness. And there’s a heck of a lot of madness, right? Certainly, how does Israel fit into all that?

You know, I mean, and I think most of us who are observers of this will say objectively that Israel is a liability to the United States. And what does actually Israel provide to the United States? Where are the American military bases throughout the Middle East? They’re not in Israel. They’re throughout the Arab nations. They’re in Turkey. They’re in the Gulf states, right? They’re in Iraq. They’re in Oman, in Egypt, et cetera, et cetera. So they’re all throughout the region, not in Israel. Where is the benefit that comes from providing support to Israel? And now you get into more softer, cultural, theological, if you will, reasons behind why the American empire does what it does. And essentially you have Israel as a colony, but it’s a colony of the West. It’s a white Western colony there. And that’s the importance of whether it’s a liability or not, you can’t take the flag down kind of thing. So I think as you start to unpack these and pull things away, you find multiple reasons for why decisions are made, whether it be Venezuela, whether it be Israel, whether it be, say, Russia, Ukraine, where each of the actors involved, whether it be individuals or institutions involved, have their own reasons to carry out these policies, to want these policies.

But in those reasons all converge in some place like Venezuela, right? So, certainly the examples are there for how this has gone in the past, and that should be plenty of reason to believe how it will go in the future.

Sara: Well, thank you so much, Matt, for joining us on TMJ. Really, really happy that I was able to get your valuable insights, and I hope to have you back on again.

Matt: Absolutely. Thank you, Sara.

The post The Donroe Doctrine appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.