The UK is one of the most wildlife-depleted countries on Earth. Yet people in England have hunted down and killed at least 140,000 of its largest remaining land predators – badgers – in the last nine years.

Government ministers have consistently claimed that this state-sanctioned massacre, which uses crude and inhumane killing methods, is borne out of necessity not barbarism. They have argued that badgers give bovine TB (bTB) to cows, and that the only way to protect farmers’ livelihoods is to do away with around 70% of badgers in areas of high bTB risk, and more elsewhere.

An explosive new study has, however, put ministers’ claims to the test. It found that killing badgers hasn’t meaningfully assisted in the eradication of bTB in the high risk area (HRA). Instead, it points to cow-focused measures, such as bTB testing, as likely being responsible for reductions in the disease.

Worse still, the study derives much of its data from government statistics, meaning ministers had all this information at their fingertips. UK politicians now have serious questions to answer about why they failed to undertake such comprehensive analysis themselves.

Filling the void

The government has asserted that killing badgers has “led to a significant reduction in the disease” of bTB in cows. But verifying this claim has been difficult due to an absence of in-depth analysis of what part the cull has played in lowering bTB in cow herds.

The latest study, authored by conservation ecologist Tom Langton, veterinarian and Prion Group director Iain McGill, and Born Free’s head of policy and veterinarian Mark Jones, fills that void. All three authors have consistently opposed the cull on ethical, scientific, and ecological grounds.

The probe covers an extensive period of time, from 2009 to 2020. It also examines all of the HRA, including 30 cull zones. This makes the study area around 37,000 sq km, approximately 30% of England. In all, the study encompasses 200,000 herd tests, amounting to millions of tests of individual cows.

Langton told The Canary that the study utilises a “comparable amount of data” to the Randomised Badger Cull Trial. This trial started in the late 1990s and was a years-long assessment of the impact of culling badgers on bTB levels in cows.

No evidence badger killing impacts bTB

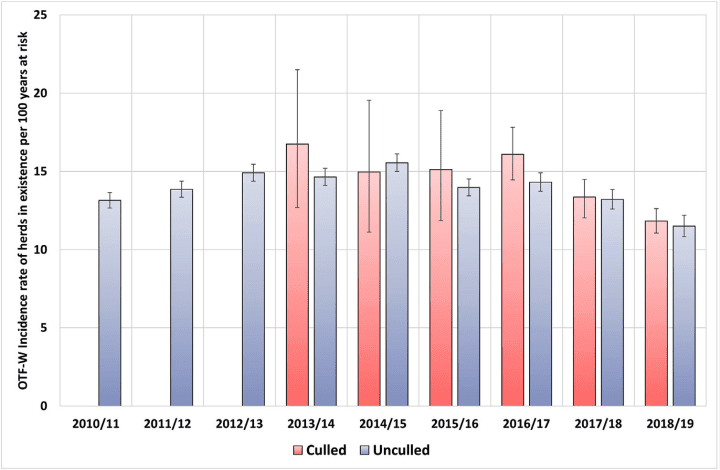

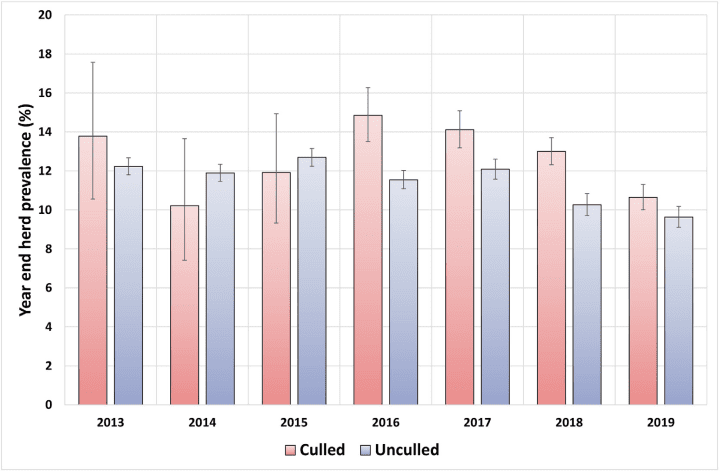

The study has been published in the Veterinary Record journal. It compared both the prevalence and incidence of bTB in cow herds in areas that had badger killing and those that didn’t. Incidence means the confirmed presence of bTB in cow herds, whereas prevalence indicates what Langton describes as “the background level of disease”, including both the confirmed and suspected presence of bTB.

As the study’s findings show, if anything, areas with culls generally had higher incidences and prevalence of bTB than areas without badger killing.

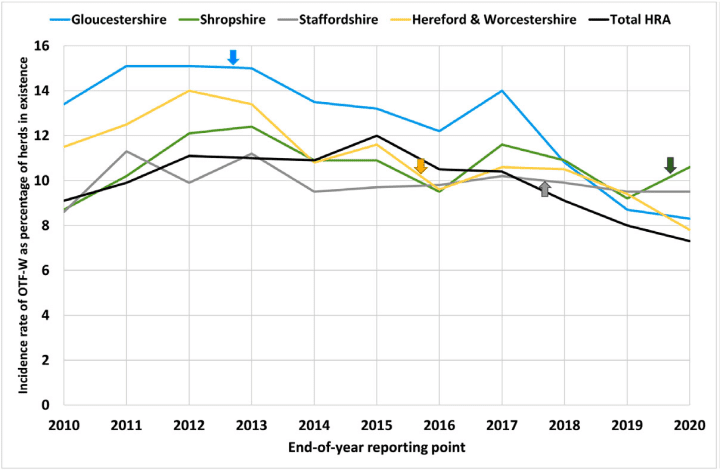

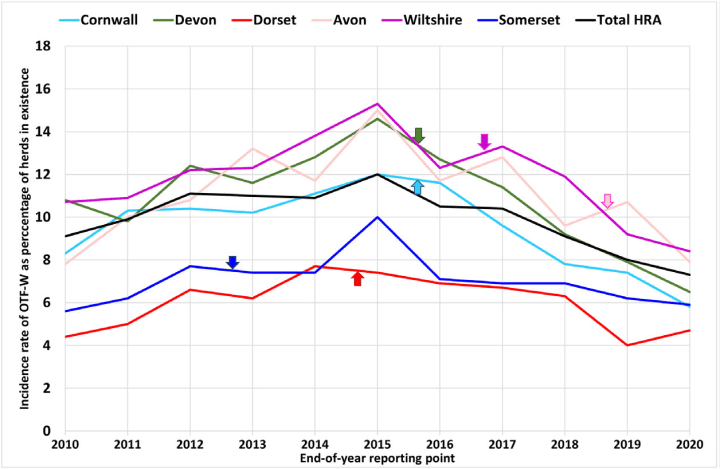

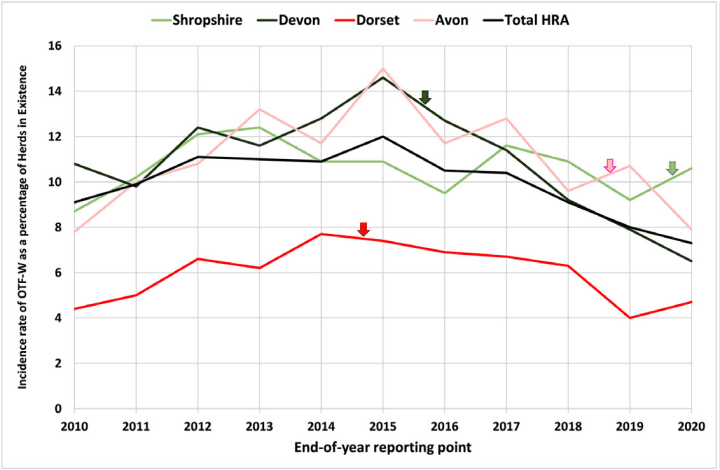

Langton told The Canary that statistics show a levelling off, and decrease in, bTB rates across much of the HRA over the last decade or so. But the study indicates that this pattern stands regardless of when each county introduced badger killing.

The arrows in the following graphs show the commencement of culling in each area. The earlier culls, such as in Gloucestershire, Somerset, and Dorset, were “small pilots”, Langton explained, with the culling rollout beginning in 2016.

Langton pointed out that all areas experienced a “slow down, levelling off, peak, and fall” in bTB incidence before the culling rollout. Somerset was the exception to this, as bTB rates “actually went up despite the first cull”, he noted.

Meanwhile, a comparison of two areas that faced prolonged badger killing, Devon and Dorset, and two that introduced culling later, Shropshire and Avon, showed a similar incidence pattern in all four areas between 2010 and 2020.

Based on these findings, the study asserts that:

The analyses do not provide any evidence for the efficacy of badger culling as a bTB control intervention.

Inferior findings

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) received this evidence in March 2021, according to Langton. The department “dismissed the findings as inferior to their highly modelled approach using undisclosed data”, he said.

Since then, the authors, and their unsung team of statisticians and researchers, have added a variety of statistical modelling to the study. Despite this exhaustive interrogation of the data, the study found that the models:

failed to demonstrate any association of culling with either the incidence or the prevalence of herd breakdowns.

Prior research

Aside from the implications the study has for the government’s bTB policy moving forwards, it also reflects very badly on politicians for failing to undertake an analysis of such magnitude themselves.

The government doesn’t even test badgers, before or after killing them, to see if they have TB. Analysis of badgers ‘found dead’, such as those killed on roads, has suggested that bTB levels among the species is low. Universities conducted this analysis and gave it to the government in July 2018 and January 2019. The government chose not to make it public for nearly two years.

DEFRA’s main contribution to available information relating to the cull consists of the quarterly statistics it publishes of bTB rates in cows. The DEFRA minister George Eustice has plucked figures from these statistics for individual years to justify opening up more rounds of killing.

Analysis of these statistics forms the basis of the new study, along with other publicly available data that Langton said required “a large amount of monitoring, extraction, checking and organization” and was “carried out by two dedicated volunteers over hundreds of hours”.

Researchers published a study in 2019 that looked at the first three pilot cull areas in the HRA and the effect of badger killing there between 2013-2017. In a finding relied on by the government to back up its culling policy, that study said Gloucestershire had seen a 66% drop in bTB incidences in cows. However, further data shows that there was a 130% increase in bTB incidences in the county’s badger killing zone in 2018.

If not badger killing, then what?

This first comprehensive study of the impact, or lack thereof, of the cull on bTB rates in cows begs a question: if the massacre of badgers isn’t driving bTB rates down, what is?

The study speaks to this too. It highlights that from 2010 onwards, the government has introduced cow-based bTB measures, such as an intensification of the TB testing regime.

The UK’s government testing system is problematic as its largely based on a test that’s only 50% sensitive. As a 2019 paper by McGill and Jones noted, that means it is likely “missing half of the infected animals” in a tested herd. DEFRA’s apparently unnecessary killing of an alpaca called Geronimo in September 2021 drew attention to the issues with the testing regime.

But measures for cows have included increasing the regularity of these tests, and applying a “severe interpretation” of them that effectively makes them more sensitive, alongside the use of other tests and control on cow movements. Langton said that the slow implementation of this “raft of measures is driving down the disease in the way that the graphs show as a rate of over 30% per five years”.

The study asserts that “taken together” with the face-value evidence that killing badgers had “no discernable impact” on bTB incidence and prevalence in cow herds in the HRA, such cow-based measures “are the most likely explanation for the changes over time”.

Langton also points to the fact that Wales has achieved a similar reduction in bTB prevalence and incidence as England between 2009 and 2020 without killing badgers. The study said this suggests that bTB “can indeed be controlled through cattle measures alone”.

End it now

The Canary approached DEFRA for comment on the study and why it hadn’t conducted such analysis itself. The department had not responded by the time of publication.

McGill described DEFRA’s failure to undertake a study of this kind as “extremely puzzling”. Jones also told The Canary that, given the cull’s purpose is meant to be tackling bTB in cows, it “seems incumbent on Government to show that the policy is achieving this aim if it is to continue to justify it going forward”.

The government’s current plan is to continue widespread badger killing until 2026. After that, the government will introduce a targeted culling policy. Langton previously told The Canary that this is an “expansion of the [culling] policy”, whereby “100% of badgers” could be targeted in smaller designated cull areas.

But in light of the study’s findings, and in the absence of evidence to back up the government’s “significant reduction” claim, Jones argues that:

after 8 years of culling during which 140,000 badgers have been killed (not including 2021 cull figures which have not yet been released), it is surely time to draw a halt to this policy which is devastating badger populations and the wider ecology, causing untold animal suffering, and costing farmers and the taxpayer millions.

Langton agrees. He concludes that:

We can be certain that badger culling was not a part of the disease coming under controls – it was cattle measures only. No further analysis can show otherwise.

He said that the government should “suspend all badger culling in 2022 and redeploy effort and finance to cattle based measures”. In the face of this study’s findings, it’s hard to imagine how the government can argue with that.

Featured image via Caroline Legg / Flickr, cropped to 770×403, licensed under CC BY 2.0

This post was originally published on The Canary.