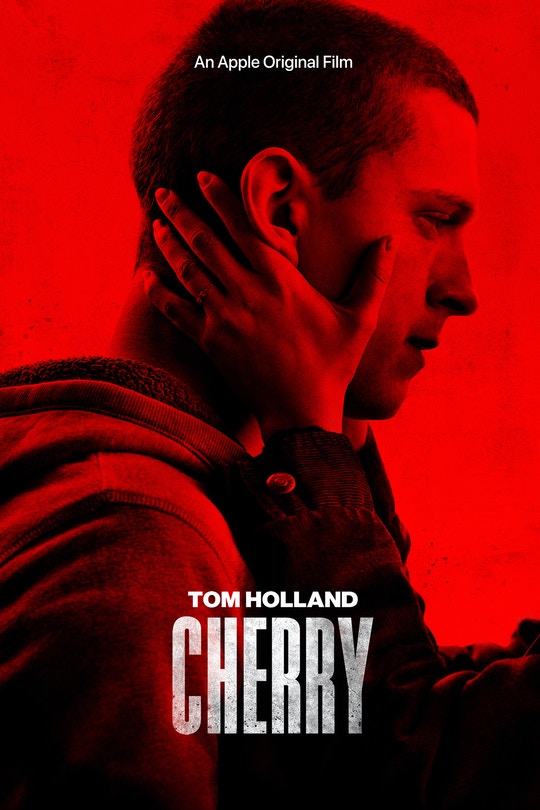

In the new film “Cherry,” the nameless protagonist — played by Tom Holland of “Spider-Man” fame — experiences an epiphany with a gun in his hand. It’s pointed at the skull of a bank teller.

A strange and messy journey has brought Holland’s character to this day, to this moment. There’s been war and drugs, and other robberies too. He seems to nod. Something has crystallized for him.

He takes off the hat and scarf serving as his makeshift disguise and asks the teller to set off the bank alarm. They are similar in age, mid-to-late 20s. The teller is Black. The robber is white.

“It’s all right,” he says, lowering the gun that had been directed at her head. “I won’t hurt you.”

Holland’s character thanks the teller. He leaves the bank, hands over the cash to the dealer he’s indebted to, and walks across a suburban street in slow motion to the heavy thrum of an orchestral score. He shoots his handgun into the air while people flee, then tosses the weapon into some nearby bushes, completing his transformation into victim. Yes, he is a victim, we are meant to gather, of society, of circumstance, of America. He sits on the sidewalk, removes his belt for a tie-off, and pulls out his rig. Police cars appear on the fuzzy horizon.

This scene is drawn from a real-life event, though a lot was subverted. There was no final fix of heroin, for starters. There was no crowd-scattering gunshot, no final debt paid, no waiting around for the authorities. Instead, Nico Walker, an Army veteran-turned-bank robber and author of the autobiographical novel on which the film is based, got stuck in traffic. The police caught up to his getaway truck, and he crashed into an embankment next to a Burger King. The money he’d stolen was in a plastic bag in the passenger seat.

There’d been no polite banter at the bank, no request for the teller to pull the alarm. Instead, in the real 2011 robbery, he’d said, “Give it to me now, you know what this is,” according to an affidavit from an FBI agent. It’d just been a robbery, like the others Walker had gotten away with, until it wasn’t.

There is at least one truth in the fiction. A bank teller was on the other end of that gun. In the film, she’s referred to as Vanessa. In real life, her name is Rosa Foster, and she was pregnant at the time of the robbery. Until I contacted her last month, she had no idea that her story was no longer her own. Her role must’ve complicated the process of turning the events at the bank into one fit for public consumption and profit. So over time and interpretations, she was pretty much removed from it.

“He has Spider-Man portraying him,” Foster told me. “Pardon me for saying this, but what the fuck?”

Erasure doesn’t have to be an act. It can be a process too.

Nico Walker.

Photo: Courtesy of the author

Some crimes are more fashionable than others.

For some offenses, we like to erase the humanity of the perpetrators. For others, we permit ourselves to erase their victims. The story of “Cherry,” from crime to novel to movie, is the story of the money to be made in understanding which crimes are which.

If one ponders this tale long enough, in all its forms, it takes on the appearance of a chameleon. The story is pure fiction with all the requisite disclaimers when it’s beneficial to be that. Then it’s the real dope when it needs to be that. Which would be standard fare if not for the tricky questions of transgression and victimhood.

The people charged with selling “Cherry” have seen what they wanted to and shaped the story accordingly.

Consistently, the people charged with selling “Cherry” have seen what they wanted to and shaped the story accordingly. Whether intentional or not, a lot of people in the entertainment machine celebrated a white bank robber while turning a Black victim into an afterthought. Apple TV has been billing the movie as “a modern odyssey.” The story behind the story, alas, is a much older one, in which only some people get full dimensionality and representation.

“Cherry” opened in theaters last month and started streaming on March 12, so Walker has been on a publicity push. In December, he and his fiancé, poet Rachel Rabbit White, posed for a Vanity Fair photo shoot. Not long after, they appeared on a GQ fashion podcast, billed as “the most glamorous couple in the world.”

Walker comes across well on the podcast, aloof but substantive. The couple discuss their new life together in Oxford, Mississippi, as he remains on supervised release after being freed from prison in 2019. He speaks on the difficulties of losing his mother to cancer during the pandemic, a hard thing for any son, but particularly one who spent much of the previous decade behind bars.

Walker says he didn’t have much to do with the film and isn’t sure he even wants to watch the finished version. The podcast hosts sound surprised, so Walker gives a more diplomatic answer, the response of an artist:

“It’s not like you own a story. It’s everyone’s story. They can tell it their own way.”

Which made me wonder: If it’s everyone’s story, is everyone involved getting their fair cut?

Still: Alamy

“I see a lot of people who commit bank robberies. … The effect it could have on the people in the bank, whether they are employees or customers or security guards or anything else. It can be profound and could last with those people forever.” — Federal District Court Judge Donald Nugent, at the sentencing of Nicholas Walker, June 1, 2012

In 2013, Matthew Johnson, co-owner of Tyrant Books, a small independent publisher, read a sympathetic profile in BuzzFeed about a soldier-turned-bank robber. This was Walker, who had served honorably in Iraq as a U.S. Army medic during the height of the war and come home to struggle with severe post-traumatic stress disorder and drug addiction. Then he began sticking up banks in the Cleveland area, getting caught and arrested on his 11th robbery. The BuzzFeed story was headlined “How a War Hero Became a Serial Bank Robber.”

Johnson initiated correspondence with Walker. Something about the young man’s story intrigued him. He sent books to the federal prison in Kentucky where Walker was incarcerated. Then he suggested that Walker write a book about his life in war and crime. The drafting and editing of a novel began soon thereafter.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the connection between war and bank robbers,” Johnson said in a phone interview. “Like the James brothers and the Civil War. … What were they supposed to do after that, go work the general store? I told Nico then, ‘Hey, if you don’t write this down yourself, you’re gonna live in the shadow of your own history.’”

There was altruism in Johnson’s outreach. There was also capitalist savvy. “I told him straight up, ‘Hey, man, you’re leaving a lot of dough on the table.’”

Still: Apple TV

Walker’s case is not one of the elusive Jesse James gang reborn. Nearly all the banks he robbed in 2010 and 2011 fell in the same 10-square-mile area of greater east Cleveland. Two occurred across the street from one another 11 days apart. Two more happened on the same boulevard seven days apart. None happened farther than 9 miles from Walker’s house. He had an addiction, a bad one, and that required funds.

Though he was facing 32 years minimum if convicted, Walker agreed to a generous plea bargain that meant 11 years in prison. The lead prosecutor happened to also be an Iraq War veteran, and it seems clear from court documents that both he and the judge factored in Walker’s combat-related PTSD. Walker would end up serving eight-and-a-half years, granted a compassionate release due to his mother’s illness.

“Do I appreciate the wrongfulness of brandishing a gun in front of someone?” Walker told BuzzFeed in his 2013 prison interview. “I don’t know… for someone who hasn’t been through what I’ve seen, I guess.”

There’s no doubt that Walker went through hell in Iraq. A line unit’s medic is exposed to the worst humanity can offer, often at a tender age. I’m a combat veteran of Iraq and served an hour away from the area Walker did. But even in combat, except for very specific and unique scenarios, soldiers aren’t supposed to point weapons at civilians. From day one of basic training, soldiers are taught that raising a weapon on someone means they are a threat and you’re pulling the trigger.

Walker’s fictional rendering of his life and exploits had found lush pastures. Now it just needed to be tidied for presentation to the literary class.

The folks at Tyrant weren’t the only ones who sensed opportunity. According to Walker, after the BuzzFeed profile was published, the author of it, Scott Johnson (no relation to Matthew), sent him a life-rights agreement that could lead to a film. Walker balked – it seemed too much.

“You will get a voice [with us],” Matthew Johnson said he told Walker. He said that when the project got underway, he had two goals for the young veteran-turned-bank robber: “Help get him in the pantheon of junkie literature” and “help him put the pieces [of his life] back together.”

A few years and a lot of revisions later, Tyrant Books sold Walker’s manuscript to the Alfred A. Knopf publishing company, part of the Penguin Random House conglomerate.

“I decided to sell to Knopf because A) I was broke and B) since Tyrant is a small press, I was afraid the book would get overlooked,” Giancarlo DiTrapano, the other co-owner of Tyrant Books, wrote in an email. While Walker credits Johnson in the acknowledgments of “Cherry” for turning his early drafts into something readable, DiTrapanao offered that he was the one who put together and edited the book.

Success, like victory, has many fathers.

On December 5, 2017, some six years after Foster was menaced by a pistol-wielding robber at that bank in suburban Cleveland, a debut was announced on the website Publishers Marketplace: Walker’s manuscript, described as “a raw, bleakly hilarious, and surprisingly poignant novel about love, war, bank robberies, and heroin,” was sold to Knopf in a “good deal.” (A good deal is defined by Publishers Marketplace as something between $100,000 and $250,000.) Eight foreign publishers purchased “Cherry” as well, each one coming with another payment.

A few months later, film rights would sell for $1 million. Walker’s fictional rendering of his life and exploits had found lush pastures. Now it just needed to be tidied for presentation to the literary class — stuffy folks, in some ways, though also a group hungry for particular narratives of redemption. The unveiling of Walker and his story would require finesse. It would need to be apologetic yet victimless.

“The ‘ordinary’ criminal who espouses a radical mode of thought has long exerted a certain hold on the literary imagination. … The man on the fringes, after all, has always been useful in defining the perimeters of bourgeois society.” — Michiko Kakutani

A book reviewer for the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani wrote a landmark essay on the Jack Henry Abbott case in 1981. Abbott was a writer whose initial sentence for forgery was extended after he killed another prisoner, escaped prison, and robbed a bank in Colorado. He was paroled in 1981, in part because of the efforts of Norman Mailer and other literati of the era.

Abbott was presented as a Dostoyevsky character come to life. Mailer went on “Good Morning America” with Abbott to showcase a writer who had “forged himself in a cauldron.” Elsewhere, Mailer spoke of idealists “drawn to crime as a positive experience — because it is more exciting, more meaningful, more mysterious, more transcendental, more religious than any other experience they have known.”

Six weeks after being paroled, Abbott killed a waiter outside an East Village café late at night. The next morning, unaware of the crime, the New York Times Book Review published a rave of his jailhouse memoir “In the Belly of the Beast.”

Walker is not Abbott. He did not kill anyone. He’s served his time and deserves to reintegrate back into society. But for a world filled with so much intellect, the high clergy of the creative arts tends to have a habit of making unforced errors. The same week I talked with Foster on the phone about the bank robbery, a scandal broke out at Poetry magazine. It had published an issue devoted to incarcerated artists but neglected to screen backgrounds. One of the published poets was Kirk Nesset, a former English professor who pleaded guilty in 2015 to possession, receipt, and distribution of child pornography and is on the sex offender registry in Arizona.

In a Twitter thread on the scandal, poet Dwayne Betts called for clearer thinking: “What is the line of people that cannot have poems published?” he asked. “Voice them joints out loud. Let’s get this aired out.”

Betts holds a Yale law degree and has served as a public defender; he also spent nine years in prison for carjacking, so his is a unique and powerful voice. His line might not be mine, or mine yours, but he’s absolutely right about the importance of defining what and where that line is. This seems especially relevant if you’re in a position of advancing someone’s art and capitalizing from it.

The author Joyce Carol Oates had some thoughts on this abdication of responsibility in 1981. “Intellectuals of the upper-middle class are vulnerable to romanticizing ‘criminal elements’ because of course they are unacquainted with them,” she told Kakutani. “We tend to romanticize things that are strange to us. No doubt the mysterious phenomenon of ‘liberal guilt’ is also operant.”

Oates also offered a different understanding of “In the Belly of the Beast” than some of her contemporaries. “To me,” she said, poking at the frenzied reception that had accompanied its publication, it was “more a literary book than an authentic book — it showed he’d read a lot.”

The cover of “Cherry,” the 2018 novel by Nico Walker.

Image: Knopf

The rollout began with a coveted profile in the New York Times. The profile explores some of the ethical issues at play with writing about one’s crimes and states that “a Knopf lawyer determined there that the novel didn’t run afoul of Son of Sam laws” — a reference to statutes that are intended to keep convicted people from profiting off their crimes. The profile also revealed that Walker was using some of the money from his publishing deals to pay off the “roughly $30,000” restitution he owed the banks. There is no mention of the bank employees he robbed.

Around this time, a group of contemporary war writers were discussing “Cherry” over email. I was part of the distribution list but not participating in the discussion; I had not yet read the book. It struck me as an inevitability, the result of 20 years of war fought abroad by an all-volunteer force. Military veterans robbing banks? It had sex appeal but was hardly new. A good nonfiction account of Army Rangers doing it in Washington state had come out just the year before: “Ranger Games: A True Story of Soldiers, Family and an Inexplicable Crime.”

Why bank robbing holds fascination in the American psyche is obvious enough. But even fashionable crimes can have long-lasting effects. Another veteran of the Iraq War, novelist Brian Van Reet, wrote an essay in 2018 about this dilemma with “Cherry” in mind:

I know it’s difficult these days to find objective moral standards we would all agree on. But perhaps we might agree it’s fundamentally wrong to stick a pistol in a pregnant woman’s face and demand money from her to fund one’s drug habit. Walker did just that in real life, yet most of the discussion surrounding his book is not about his victims. … Is there something especially romantic for Americans about bank robbers and broken veterans — so long as they’re clean cut and white?

Someone on the distro list forwarded to everyone else an email from Walker’s editor at Knopf, Tim O’Connell. He’d read Van Reet’s essay.

“Some of the details are a little off,” the email from O’Connell stated. “For example, Nico never pointed a gun at a pregnant women [sic]. Unless [Van Reet] knows something I don’t.”

This email surprised me. An editor should be expected to defend their author. But the description of Walker pointing a gun at a pregnant Foster was in the first paragraph of the BuzzFeed article. Even I knew that, and I was trying not to care about any of it. This was my first experience with “Cherry” being less a story about war or addiction or robberies than it was a cipher. Knopf had received a fiction manuscript based on real events from the folks at Tyrant Books. Their job was to shape the manuscript into publishable form. So they did that.

The writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has warned about “the danger of a single story.” Humans are storytelling creatures, of course, and sometimes we seek ease and comfort from stories because life offers anything but. The tale of the battle-scarred bank robber rebelling against the society that sent him to war is an old and known one, and “Cherry” updated it for a new century. But as Adichie cautions, “[S]how a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.”

Often in stories of crime, the victims become flat nobodies, props for dark morality plays that focus on the perpetrator. “It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power,” Adiche goes on. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.”

“Cherry” is a single story, aggressively so, with various strands to pull. Only some of these strands offered the possibility of success and coin, a lot of coin, if things broke right. A book that included the victims of the crime in a substantive way might not have been impossible, but it would’ve been difficult. And besides, “Cherry” was a fiction borrowing from life, not a chronicle of it. So no one pulled at that strand, and no one bothered to reach out to Rosa Foster.

Rosa Foster on Feb. 28, 2021.

Photo: Courtesy of Rosa Foster

“That particular bank teller was fairly far along in her pregnancy and had to receive medical treatment for anxiety.” — Assistant U.S. Attorney Arturo Hernandez, at the sentencing of Nicholas Walker, June 1, 2012

Until I emailed Foster in February, she didn’t know about “Cherry” the novel or “Cherry” the film. No one from Walker’s publisher or the production company, and not a journalist who’s written about either, had bothered to reach out to the woman mentioned by name in the first paragraph of the article that set all this in motion.

When we talked on the phone, Foster was still a bit shaken by what she had learned from my email. She is in her late 30s, a mother, African American, an entrepreneur who’s worked hard in the years since the robbery to earn her notary license and establish her own local clothing line, the Green Rose Experience, which caters to individuals in transition.

“No one has called me about anything, period,” she said.

She said she needed to talk to her lawyer, but she also kept speaking.

“What happens to other victims?” she asked rhetorically. “If I were a rape victim, no way there’s a movie. … It was a horrible day.”

I asked her to confirm that she was pregnant at the time.

“Yes!” she said. “Who points a gun at a pregnant woman?”

Her fury was real and still forming, understandable when you consider that her victimhood has been monetized without consent. As many a combat veteran can attest, trauma lingers, warps, adapts, claws across one’s soul in the emptiest of moments, just because it can. Some of the finest writing in “Cherry” touches upon the nature of trauma. But military veterans cannot lay singular claim to it.

Walker robbed 11 banks from December 2010 to April 2011, most by pretending to have a gun, the last two actually having one. So in addition to Foster, there were at least 10 other tellers. Ten more stories, 10 more horrible days. Both the novel and the film use the clever line, “One thing about robbing banks is you’re mostly robbing women so the last thing you want to be is rude.” Walker’s novel describes one teller as looking “like Janet Reno.” Another “had a fat face … she glared at me with little red pig eyes.”

Foster’s equivalent in the film is named Vanessa, the teller of the final robbery. Vanessa neatly matches Foster’s race, gender, and age at the time. The actress Tamara Austin plays the role well. She keeps her cool while conveying absolute fear for her life, staring down the barrel of a handgun.

In contrast, the Vanessa of the novel is “pale as I am. … Her eyes are blue with flecks of gold.” This seems to be a deliberate break considering how much this scene has in common with real life. In all variations, attention is called to the blue hoodie the protagonist is wearing to appear like an ordinary citizen. All the renderings of the robbery, real and otherwise, have Walker delivering virtually the same line to a teller: “It’s not personal” or “It’s nothing personal.” And the book’s setting for the final robbery is simply the setting for Walker’s second-to-last robbery, a Key Bank in Cleveland Heights.

The very first page of “Cherry” carries a disclaimer: “This book is a work of fiction. These things didn’t ever happen. These people didn’t ever exist.”

Poster for “Cherry,” the 2021 film.

Image: Apple TV

The line becomes an actual line when laws are broken. So-called Son of Sam laws (named for serial killer David Berkowitz) keep convicted people from profiting off their crimes. Sometimes money can be seized and given to victims. Under New York state’s Son of Sam law, when people convicted of certain crimes receive at least $10,000 for reasons related to those crimes, victims must be notified.

The original Son of Sam law was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1991. States began introducing revised laws in the aftermath. New York’s current version of the law has been in place since 2001. In 2019, it was invoked against Anna “Delvey” Sorokin, a fraudster of the trust-fund socialite class who became infamous from a magazine article, “How Anna Delvey Tricked New York’s Party People.” Sorokin was found guilty of second-degree grand larceny for scamming approximately $275,000 from acquaintances and businesses. The state froze $140,000 that she received from Netflix for the rights to her story (“Inventing Anna” is due out in the near future). According to The Wall Street Journal, the state’s action is “clearing the way for two of her victims, both banks, to pursue court action.”

Could a similar twist happen with Walker? That’s not certain, because federal law requires that the offense involve “physical harm to an individual.” According to Eric Rosen, a white-collar crime expert and partner at the law firm Roche Freedman, “the bank tellers undoubtedly suffered harm, [but] it does not appear that this harm was physical.”

An aside: This is a sordid tale, full of exploitation. However you feel while reading about it, it’s likely that I felt something similar while writing about it. If I hadn’t contacted Foster, maybe she could’ve lived her life without ever knowing about “Cherry,” and maybe that would have been better for her. Unlikely, but possible.

I have other cards to lay on this table.

It’s not lost on me that I could be accused of some version of exploitation by reporting on all this. This story took about a month of work, for which I’ll be paid a bit more than one month’s rent in north Brooklyn. Thirty percent will be set aside for taxes. Most of the rest will go to my sons’ college funds. I’ll probably get a little drunk the night this story publishes, an old tradition from a decade of scraping by as a freelancer. I’ll regret doing so the next morning when our eldest boy launches into consciousness

I first came to examining the history and architecture of “Cherry” as a veteran of Iraq who’s invested in how vets are portrayed in American society. Too invested, perhaps. I’ve written three books about war, veterans, and America. All have been modest successes of which I am proud. None were as commercially successful as “Cherry.”

Do I understand why? Of course.

Walker enlisted in the Army. I was an officer, a college boy, before I joined up. I had soldiers in my scout platoon he reminds me of, a little streetwise, a lot aimless. Some of them have had a rough time since we got home. Others have thrived. None have robbed a bank, though a guy from our sister platoon did.

A lot of soft-handed middlemen have made money from this mean, unfortunate story that does not belong to them. It belongs to Foster, it belongs to Walker, and it belongs to some other folks too. But it does not belong to them.

I thought Walker looked like he was trying too hard at the robber-turned-scribe bit in the Vanity Fair photo shoot until something Johnson said over the phone landed: Between the military and prison, Walker had been confined for a long, long time.

Now I think, let the guy wear some mascara, who cares. It takes courage to serve one’s country, especially in a time of war, even a stupid war, and a lot of book reviewers skipped over that in their takes on “Cherry.”

Betts, the poet, said that it’s important for us to articulate our line. Walker doesn’t cross mine. It’s fine for him to make art, I think, even art about his crimes, and profit from it. Walker can write well. He wasn’t a victim, though, and I believe there’s been a simultaneous lack of scrutiny and excessive celebration of his bank-robbing past.

Should Foster and maybe some of the other tellers be financially compensated for having their victimhood fundamentally erased and subsequently exploited? I think that too, though I’m no lawyer. Further, I don’t think it’s Walker who should have to pay. He’s paid his restitution. He robbed Foster, true enough, but he’s not the one who hired an actress of her exact race, gender, and age to play her exact position in a big film that’s screening across the world.

Then again, regarding that question of restitution, it always seems to just be about the banks. In a profile of Walker that was published a few days ago in The Ringer, the reporter wrote that he told Walker, “The banks don’t deserve your ‘Cherry’ money” — like nothing else and no one else was involved at all in the robberies. Which is how a lot of journalism covering this story has gone since the original profile in BuzzFeed back when.

More than anything, at the end of this, I’ve been filled with a gnawing anger that a lot of soft-handed middlemen — some other genders, too, I guess, but mostly men, let’s be honest, this story could use some honesty — from New York to Hollywood have made money from this mean, unfortunate story that does not belong to them. It belongs to Foster, it belongs to Walker, and it belongs to some other folks too. But it does not belong to them.

That’s America, though.

It’s hard legal record that Walker “did knowingly use, brandish and carry a firearm” in the commission of a bank robbery on April 23, 2011. That’s one of the counts he pleaded guilty to, and it applies to the U.S. Bank Foster was working at that day.

But did he point the handgun at her? That’s what the BuzzFeed article stated, and it’s what the federal prosecutor said at Walker’s sentencing in no uncertain terms: “The last two robberies he chose to use a gun, and in both of those, he pointed the gun at bank tellers.”

Walker says he did not. I reached out to him over email with a list of four short questions. He responded with a thorough 3,500 words, mostly a one-paragraph block that he typed on his phone.

“The gun was in the bottom of a plastic bag,” he wrote. “When I entered the bank I was holding the gun, only where it could not be seen. … As soon as I walked into the bank I [put] the gun into the bag.”

Walker’s recollection of the armed robberies continued:

The gun was such a non-factor in this event that there is not one security photo of me holding a gun in that bank in the government’s discovery packet. … But then there is the photo of me from the previous Tuesday, the 18th of April, and I am unequivocally pointing a gun at someone there, right? I am afraid not. I do not know why anyone would want to make a film about this. I am not a war hero and I didn’t even point a gun at anybody one time in a robbery. If that were true, then how do I account for the security photo? I walked into the bank and flashed a pistol. True enough, I did that, and that is not okay. It is definitely not okay to walk into a bank and flash a pistol. And I did. What I did not do was point it at anybody. Sometimes an FBI agent will lies [sic]. Sometimes an AUSA [assistant U.S. attorney] will lie. It happens. I have seen it happen in my own case, and I have known it to happen in other cases. In this case, the photo was stopped at an advantageous point for making me look a bit worse of a bad guy than I actually am. I was not pointing a gun at anybody. I was bringing the gun down from being pointed at the ceiling.

If all that’s true, then why plead guilty, even to a generous deal? Perhaps the answer lies in Walker’s reply to why he considered, in 2013, signing the life-rights agreement with the writer of the BuzzFeed article: “I was under a considerable amount of pressure to lessen the financial burden on my parents, who had paid money for a lawyer,” he wrote in his email. “There was no upcoming means by which I could repay that debt.”

There it is again — money. In all the disparate parts of “Cherry,” it almost always came back to that. Who was making it, who was losing it. Some played the game better than others. Some didn’t even know there was a game to be played.

“Today Nick celebrates that no one was injured. … When he was caught on April 23rd of 2011, he began what we now know is a restorative process. … He realizes now that his crimes were not victimless.” — Defense attorney Roger Synenberg, at the sentencing of Nicholas Walker, June 1, 2012

Glowing reviews for “Cherry” arrived in the summer of 2018 like a dream. Vulture proclaimed it “the first great novel of the opioid epidemic,” with reviewer Christian Lorentzen celebrating it as “the rare work of literary fiction by a young American that carries with it nothing of the scent of an MFA program.” In Harper’s Magazine, Atticus Lish called attention to the book’s “extraordinary, vivid language” and marked Walker as a “dissident” to the war. More accolades followed, including an appearance on the New York Times bestseller list and eventual selection as a PEN/Hemingway Award finalist.

Does “Cherry” hold up to that hype? Like most first novels, its quality is uneven. It’s very funny and stark in spots, but it still has its pretenses. It contains references to J.D. Salinger and Prometheus, metaphors involving bird nests, a scene where poems are sent to (and ignored by) the New Yorker. The influence of MFA kingpin Barry Hannah, who is cited in the acknowledgements, looms on every page. One may not exactly know the meaning of the line, “We would get to screaming at one another, then fuck and sleep like young wolves in a shoe box,” but stylized nihilism sometimes means fudging on clarity. What the Vulture review really meant: Robbing banks is hip. Going to graduate school is not.

As for Walker’s war dissidence, this is the closest thing to a political statement in the book: “It was only a coincidence that I had been to a war and the war probably hadn’t had much to do at all with my being fucked in the head.”

Over the years, Walker’s been asked how much truth is in “Cherry.” It’s a loaded question that survivors of war or catastrophe can probably identify with — no interest in the person or journey, only the spectacle.

That’s fine writing, and brazen. Having your autofictional proxy admit that he was a dirtbag before the war cuts against easy banality. That the book elsewhere reinforces other preconceived notions about military veterans is forgivable, as those pitfalls are many, and Walker is hardly the first young author to step into one. (I’ve done it myself, I am certain.) And besides, he lived those notions! Isn’t that much of the appeal of a work like this?

Over the years, Walker’s been asked a lot about how much truth is in “Cherry.” It’s a loaded question that survivors of war or catastrophe can probably identify with to some degree — no interest in the person or journey, only the spectacle. Still, it’s a natural enough thing to wonder about, with an answer that should, in theory, be somewhat fixed.

Mother Jones asked in 2018: How autobiographical is “Cherry”?

Walker: “I lose track. … I’d have to try hard to sort out what was real and what wasn’t.”

The Guardian asked in 2019: Is the book autobiographical?

Walker: “On a very basic level it isn’t what happened to me.”

I asked over email in 2021: How does it feel to have your life portrayed and dramatized?

Walker: “In as much as the book is not my life, and the film is not the book, I [do] not look at it as my life on the big screen.”

And the armed robberies?

“I was being very inconsiderate,” he told Mother Jones.

I asked how he looks back on the robberies.

“It was never part of my life. … As long as no one literally eats me, I could not care less about how I am perceived. There was a time when I fell short of what I wanted of myself, and so that is why I say that I have not lived well. As for the standards of the world at large, they are too inconsistent and absurd to be credited. I believe in God, not scolds.”

Even the federal government has wondered where life ended and story began. In a September 2019 email about Walker’s request for compassionate release, his lawyer, Angelo Lonardo, wrote to the Offices of the United States Attorneys, “You related the government’s concern that someone would seek an early release based upon the fact that he wrote a book about his crimes and made money off of it. [The novel] relates a story based upon a fictional character which has meaning, and gives meaning, to people who experience crisis in their lives. This is not a story about bank robberies.”

That’s perhaps true, though the book sure has been pitched, sold, and marketed as a story about bank robberies.

At Walker’s sentencing on June 1, 2012, he said that he would “like to apologize to the bank tellers, bank workers, the drivers, passengers that I endangered and who I intimidated and frightened.”

Which is a hard thing to square with: “This book is a work of fiction. These things didn’t ever happen. These people didn’t ever exist.”

But, well, writers.

Photo: Apple TV

The Russo brothers acquired the film rights during the fever pitch of the “Cherry” rollout in the summer of 2018. The filmmakers later sold worldwide streaming rights to Apple Original Films for something in the “mid-$40 million range.” Not bad for a story that began with a stolen $7,400 seized from Foster in 2011.

Despite his reticence to watch the entire film, Walker’s listed as an executive producer, as is Johnson, now working as Walker’s manager and agent.

The film character played by Holland is supposed to be understood as a victim, and there’s some truth to that. Young people seeking purpose can get sucked into the armed forces and exposed to horrors and violence that they may be unequipped to handle, then returned to civilian society with little training for reentry. That the character becomes a perpetrator himself is a dark irony but not one dwelled upon in the film: There’s a redemptive montage to get to, which closes the film.

The deeper dark irony? The muddying up of victims and perpetrator? The film didn’t quite get there, though Holland realized what was happening, or not happening.

In a Variety interview, the actor admitted that during filming, “when the alarm would go, and I’d be pointing a gun in this poor lady’s face, I could not shake that what I was doing was wrong. Of all the things I had to do in that film, that’s the only thing that lasted for me.”

Many people made money from what happened in that bank in suburban Cleveland. New York editors and go-betweens, Hollywood agents and filmmakers, and others, all sticking their hands into the big “Cherry” pie and pulling out green.

Many people made money from what happened in that U.S. Bank in suburban Cleveland in April 2011. New York editors and go-betweens, Hollywood agents and filmmakers, and others, all sticking their hands into the big “Cherry” pie and pulling out green. That the underlying story at one point included real people and real victims: This was erased through careful, diligent inattention. Of all those people involved in that erasure, from criminal act to blockbuster film, the actor seems to be one of the few willing to say publicly that he spent time considering why.

I asked Walker about this over email, if he thought that the bank tellers, particularly those of the armed robberies, deserve any financial compensation.

“I wonder why you didn’t ask this question about the Iraqis,” he replied.

That was the entirety of his answer. A pithy zinger, and he’s certainly not the only soldier-turned-author to ponder the ethical maze of writing about war. Still, after thinking it over, I realized how much of a dodge his reply was. By all accounts, Walker served honorably in Iraq. Fellow soldiers testified to that fact in order to help keep the federal government from crushing him when he was facing 32 years of prison. But my question wasn’t about Iraq. It was about his actions at home and how all these many people not named Rosa Foster have profited from warped versions of those actions.

When told of Walker’s denials that he ever pointed a handgun at her, Foster replied through her attorney: “Acknowledgment, although not often given by those who have caused hurt and harm, helps aid in the healing process. It allows all involved to have the proper amount of blame and responsibility for their actions. Nico has had his chance to heal and move forward, and I pray that this will allow me to do the same.”

At a point in my reporting, Foster stopped responding to requests for a second interview. So I decided to poke around on Facebook and found her profile. Many of her posts were public. I found a recent one with a lot of sad-face emojis beneath it. (Foster would later grant me authorization to use both her name and the Facebook post.)

The post read: “Bank Robbers … They steal your dignity and once it starts you will never be the same again … pray my strength today. #healinghurts #hugesigh”

I considered the ethical issues of reading the post, let alone quoting it. It was obviously intended for family and friends. I clicked down to read the comments.

Writing. Well. It’s sometimes ugly business.

A friend asked Foster if she’d been robbed at the bank.

“10 yrs ago and 4 years,” Foster replied. “But reminded daily.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.