Jairo Bolledo in Manila

Karl Patrick Suyat, 19, has no personal experience of the tyrannical rule of late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos. But memories of the atrocities and human rights violations committed during those dark moments have transcended time.

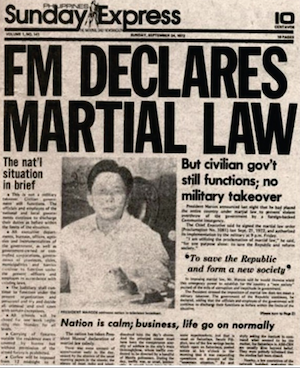

The year 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law. But this year also saw the return of the Marcoses to power — Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is now the President of the republic and spoke yesterday at the UN General Assembly.

Despite efforts of Martial Law survivors, human rights groups, and even academics to remind the Filipino people of the abuses of the Marcos family, Marcos Jr was still able to clinch the country’s top post.

- READ MORE: Networked propaganda: How the Marcoses are using social media to reclaim Malacañang

- Networked Propaganda: How the Marcoses are rewriting history

- Martial law brutality in ‘educational’ musical drama Katips touches raw nerve in NZ – David Robie

- Martial Law Day in the Philippines

Fueled by outrage and anguish, Suyat thought of a way to channel his energy and still fight back despite the Marcoses’ victory — he founded “Project Gunita” (remember) along with Josiah Quising and Sarah Gomez.

Project Gunita is a network of volunteers and members of various civil society organisations that aim to defend historical truth. They particularly push back against historical denialism and protect truths about the Martial Law years.

Through the project, the three founders and their members created a digital archive of all materials that contain information about Marcos’ Martial Law to preserve them.

Archiving is not new since other government offices and groups like the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation and the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, under the Commission on Human Rights, have made efforts to preserve Martial Law materials.

But Project Gunita is born out of the spirit of volunteerism and nationalism among young Filipinos.

From old newspapers, magazines, and books — Project Gunita members seek and buy materials, and then scan them to be preserved in the archives. The project’s archiving started right after Marcos Jr’s victory.

“Having read through the history of dictatorships, from Benito Mussolini to Adolf Hitler to Ferdinand Marcos himself, lagi’t-laging ang unang hinahabol, ang unang-unang tinatarget ng mga diktador ay ‘yong mga silid-aklatan, libraries, at ‘yong mga arkibo – the archives (always, the ones being targeted first by dictators are libraries and archives),” Suyat told Rappler.

Suyat believes that the Marcoses won’t be content with just distorting and whitewashing the atrocities of the Marcos administration. They would eventually go after the archives to erase the truth, Suyat added.

“The only question is when, it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when. And I don’t want to wait until that time happens before we start to scramble around to save the archives.

“Habang may panahon pa (while we still have time), while we can still do it, ‘di ba? (right?) Bakit hindi natin gagawin? (Why don’t we do it?).”

Even before Marcos Jr’s victory, journalists have pointed out that his family not only revises history, but also introduces an alternative history that favours them. The Marcoses also rode on various disinformation networks to disseminate falsehoods.

A two-part investigative story by Rappler showed how the Marcoses used social media to reclaim power and rewrite history to hide their wrongdoings.

Passing the torch

The personal experiences of Project Gunita founders fanned their desire to continue the fight of the generation who came before them. Suyat, who grew up in a family of Martial Law survivors, feels it is his responsibility to protect their stories.

“I cannot allow their stories, as well as the stories of people I had gotten acquainted with later in life who are Martial Law survivors to be erased by historical denialism, that we all know is being perpetrated by the Marcos family,” Suyat told Rappler in a mix of English and Filipino.

Josiah Quising, a co-founder of Project Gunita and a lawyer, believes that these stories should be preserved because true justice for Martial Law victims has yet to be attained.

“It’s very frustrating ‘yong justice system sa Pilipinas and how, for decades, ay wala pa ring totoong hustisya sa mga nangyari during the Martial Law era,” Quising told Rappler. (It’s very frustrating, the justice system in the Philippines, and how, for decades, there has been no true justice for everything that happened during the Martial Law era.)

On the inauguration of Marcos Jr, Martial Law survivors led by playwright Boni Ilagan pledged to continue guarding against tyranny.

In the same event, they had a ceremonial passing of the torch, which symbolized the passing of hope and responsibility from Martial Law survivors to the younger generation.

Suyat and Quising believe that their generation is equally responsible for guarding the country’s freedom — at least in their own way. They strongly believe that since the government is now being led by the dictator’s son, they cannot expect it to preserve the memories of Martial Law, so they have to step in.

Preserving truths from generation to generation

“Wala ka namang naririnig.

‘Di ka naman nakikinig

Parang kuliling sa pandinig

Kayong nagtataka

Ha? Inosente lang ang nagtataka,”

Inosente lang ang nagtataka by Bobby Balingit

(You hear nothing. But you are not listening. Like a chime to the ear. You who wonder. What? Only the innocent wonder.)

This song comes to Kris Lanot Lacaba’s mind whenever he hears people deny the atrocities of Martial Law. His father, Pete Lacaba, a poet and journalist, was tortured and arrested under the Marcos regime.

As a son of a Martial Law survivor, Lacaba has heard stories of torture and violence straight from the victims themselves. He recalled that it was on the pavements of Camp Crame, where his father was imprisoned, that he learned how to walk.

Even though decades have passed since those dark periods, he still vividly remembers how his father became a victim of Marcos’ oppressive rule.

“Ang ginagawa ro’n, may dalawang kama tapos pinapahiga ‘yong tatay ko, ‘yong ulo niya sa isang kama, ‘yong paa niya sa isang kama. At ‘pag nahulog ‘yong kama niya ro’n eh gugulpihin pa siya lalo (What they did to my father was, there were two beds and they would tell my father to lie down, his head on one bed, and the other, on the other bed. If he fell, he would be beaten further),” Lacaba told Rappler.

Aside from his father, his uncles Eman Lacaba and Leo Alto were both killed during Martial Law. It is extremely hard for Lacaba to respond to people who deny that human rights violations happened under Martial Law.

Now that he has his own children, Lacaba passes on the stories of Martial Law to them so the memories would be preserved.

“Mahirap eh, bilang magulang. Paano ba natin ikukuwento ito? Pa’no ba natin ipapamahagi ‘yong karanasan ng magulang nila at ng mga lolo’t lola nila?” Lacaba said. (It’s hard as a parent. How do we tell this story to the kids? How do we tell the kids about the experiences of their parents and grandparents?)

He even thinks of ways to make the stories appropriate to his children.

“So kinukuwento namin sa mga bata, ‘no? Hinahanapan namin ng paraan na maging appropriate sa age din nila ‘yong mga kuwento.” (So we tell the stories to my children. We find ways to make the stories appropriate to their age.)

Aside from his kids, Lacaba says he would always accept invitations by schools and universities to share the Martial Law story of his family. He believes that in this way, he will not only share the truths he learned from his father, but get to listen to other stories, too.

After all, Lacaba believes, conversation about Martial Law should reach everyone.

Republished with permission.