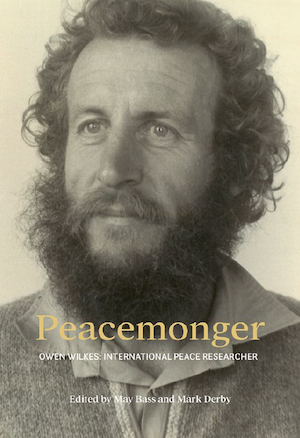

Peacemonger, the new book published last month to celebrate the life and work of peace researcher and activist Owen Wilkes (1940-2005), is being launched in Auckland on Friday. Here a close friend from Sweden — not featured in the book — remembers his mentor in both New Zealand and Scandinavia.

COMMENT: By Paul Claesson in Stockholm

I got to know Owen Wilkes through friends in 1980, when as a 22-year-old student I ended up in a housing collective where his ex-partner lived. He was then at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), having recently arrived from the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), and was, in addition to his collaboration with Nils-Petter Gleditsch, already in full swing with his Foreign Military Presence project.

He hired me as an assistant with responsibility for Spanish and Portuguese-language source material.

During this time I got to know Søren MC and Kirsten Bruun in Copenhagen, who had recently launched the magazine Försvar — Militärkritiskt Magasin. I contributed a couple of articles and was then invited to participate in the editorial team.

A theme issue about the American bases in Greenland grew into a book, Greenland — The Pearl of the Mediterranean, which apparently caused considerable consternation in the Ministry of Greenland. The book resulted in a hearing in Christiansborg.

I was also responsible for a theme issue about the DEW (Early Warning Line) and Loran C facilities on the Faroe Islands. I was in Stockholm when SÄPO’s spy target against Owen started, and I was there the whole way.

SÄPO interrogated me a couple of times, and at one point during the trial, when I took the opportunity to hand out relevant material about Owen’s research — all publicly available — to journalists in the audience, I was visibly thrown out of the case by a couple of angry young men from FSÄK (the security service of the Swedish defence establishment).

Distorted by media

Owen and I saw each other almost every day — sometimes I stayed with him in his little cabin in Älvsjö — and together we wondered how his various activities, such as his innocent fishing trip in Åland, were distorted in the media by FSÄK and the prosecutor’s care (SÄPO had subsequently begun to show greater doubt about Owen’s guilt).

In 1984-85, after he had been expelled from Sweden, I was Owen’s house guest at his farm in Karamea, Mahoe Farm, on New Zealand’s West Coast, at the northern end of the road. He was in the process of selling it.

With his brother Jack, he had started a commercial bee farm, and together we spent an intensive summer — harvesting bush honey, pollinating apple and kiwifruit orchards and building a small harvest house for the honey collection.

In the meantime, we sold — or ate up — the farm’s remaining flock of sheep. When the farm was sold, we moved to Wellington — I was offered a room in the Quakers’ guest house, where I joined the work at Peace Movement Aotearoa’s premises on Pirie Street.

Then Prime Minister David Lange had recently let New Zealand withdraw from ANZUS, as a result of his government’s refusal to allow US Navy ships to call at port unless they declared themselves disarmed of nuclear weapons.

As a result, PMA organised a conference with the theme nuclear-free Pacific, with participants from all over the Pacific region. Together with Owen, Nicky Hager and others I contributed to the planning and execution of the conference.

Surveying US signals intelligence

Before this, Owen and Nicky had begun surveying American signals intelligence facilities in New Zealand. I took part in this, ie. with a couple of photo excursions to Tangimoana.

Owen and I kept in touch after my return to Sweden. What I remember best from his letters from this time — apart from his musings about his work as a government defence consultant — are his often comical anecdotes about his adventures in the bush as a scout for the New Zealand Forest Service, where his task was mainly to map Māori cultural remains before they were chewn to pieces by the forest industry.

His sudden death took a toll. I got the news from his partner May Bass. I would have liked to have flown to NZ to attend the memorial services for him, but ironically they coincided with my wedding.

Owen played a very big role in my life. I admired him, and miss him all the time. More than anyone else I have known, he deserves to be remembered in writing. I was therefore very happy when I heard about the time and energy devoted to this book project. My sincere gratitude.

- Peacemonger: Owen Wilkes: International peace researcher, edited by May Bass and Mark Derby. Wellington: Raekaihau Press, 196 pages. $35. ISBN 978-1-99-115386-9

- Book launch: 5.30-7.30, 16 December 2022, Trades Hall, 147 Great North Road, Grey Lynn. All welcome. More information