This weekend, the news emerged that Noam Chomsky, the 95-year-old titan of the left, had suffered a decline in his health and, as Bev Stohl, his former assistant at MIT, put it, it was “unlikely he will return to the public eye.”

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact Chomsky’s work has had. Beyond the total transformation of his academic field (he’s widely acknowledged as the father of modern linguistics and the main force behind the cognitive turn in the sciences), his political impact has been immeasurable. As a writer, activist, analyst and critic of power, and likely the most visible left public intellectual of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, his work has defined the terms of countless debates and he’s been a tireless advocate for — and guide on the path to — a better future.

Our thoughts are with Chomsky, and we expect that he’s on many of your minds as well. So this week we’re opening up this long excerpt from a great conversation Anand had with him four years ago, focusing on his interesting and not necessarily intuitive leftist case for supporting Biden against Trump in the 2020 election, the power of movements to shape politics, and a ton of other still timely matters, including what he thinks about the question of his own legacy. We think you’ll find it insightful, poignant, and —above all — motivating.

Each week, we excerpt a piece from our archives for our free subscribers to enjoy. If you appreciate these posts and the labor that goes into them, we’d be honored if you’d join us as a paid subscriber.

The interviews and essays that we share here take research and editing and much more. We work hard, and we are eager to bring on more writers, more voices. But we need your help to keep this going. Join us today to support the kind of independent media you want to exist.

And we’re offering new paying subscribers a special discount of 20 percent. You will lock in this lower price forever if you join us now!

Get 20% off forever

“Real politics is constant activism”: A conversation with Noam Chomsky

There’s this discussion on the left about whether it’s important at this moment to be quiet about a lot of the usual issues and just focus on getting rid of Trump. Or, on the other side of the argument, that this is exactly the time to raise all those other types of issues and to be tough on Biden. How do you understand that debate?

Well, there is a traditional left position, which has been pretty much forgotten, unfortunately, but it’s the one I think we should adhere to. That’s the position that real politics is constant activism. It’s quite different from the establishment position, which says politics means focus, laser-like, on the quadrennial extravaganza, then go home and let your superiors take over.

The left position has always been: You’re working all the time, and every once in a while there’s an event called an election. This should take you away from real politics for 10 or 15 minutes. Then you go back to work.

At this moment, the difference between the candidates is a chasm. There has never been a greater difference. It should be obvious to anyone who’s not living under a rock. So the traditional left position says, “Take the 15 minutes, push the lever, go back to work.”

Now, the activist left has not been making the choice that you mentioned. It’s been doing both.

Take Biden’s campaign positions. Farther to the left than any Democratic candidate in memory on things like climate. It’s far better than anything that preceded it. Not because Biden had a personal conversion or the DNC had some great insight, but because they’re being hammered on by activists coming out of the Sanders movement and others. The climate program, a $2 trillion commitment to dealing with the extreme threat of environmental catastrophe, was largely written by the Sunrise Movement and strongly endorsed by the leading activists on climate change, the ones who managed to get the Green New Deal on the legislative agenda. That’s real politics.

This is interesting coming from you. Your support for Biden is more than merely grudging. You actually seem to think that the platform is surprisingly good given who he is and given where we are.

This is not support for Biden. It is support for the activists who have been at work constantly, creating the background within the party in which the shifts took place, and who have followed Sanders in actually entering the campaign and influencing it. Support for them. Support for real politics.

The left position is you rarely support anyone. You vote against the worst. You keep the pressure and activism going.

So given this popular ferment you’re talking about, a question about a leader. I wonder whether you think a figure like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez could ever become president in this country.

Well, if you’d asked me 10 years ago whether someone like Bernie Sanders could be the most popular political figure in the country, I would’ve said you’re out of your mind. But it in fact happened in 2016 and it’s continued to create a significant movement. There are real possibilities. I think if you take a look at the United States in the 1920s, and you asked, Could there ever be a labor movement?, you would’ve sounded crazy. How could there be? It had been crushed.

But it changed. Human life is not predictable. Depends on choices and will, which are unpredictable. So right now, for example, we’re in the process of formation of a Progressive International. It’s based on the Sanders movement in the United States and Yanis Varoufakis’s DiEM25 movement in Europe, which is a transnational European movement seeking to preserve and strengthen what makes sense in the European Union and to overcome its very serious flaws.

If you ask now whether it’s a prospect, it would be very hard. If you take a look at it objectively, you look at where power is distributed in the world, you’ve got the Progressive International made up of these forces, and then you have a “reactionary international” being crafted in the White House with Trump running it. Quasi-dictators like Bolsonaro, a Trump clone, are part of it. The Middle Eastern dictators, family dictators of the Gulf states. Sisi’s Egypt, the worst dictatorship in Egyptian history. Israel, which is moving so far to the right you can barely see it, is part of it. Modi’s India, trying to destroy Indian democracy, turn it into a fundamentalist Hindu quasi-dictatorship. Orban in Hungary.

You compare those forces, and it looks like, How could this even be a struggle? But that’s the wrong measure. There are people, and they make a difference.

We can go back to my favorite philosopher, David Hume. His Of the First Principles of Government, a political tract in the late 18th century, starts off by saying that we should understand that power is in the hands of the governed. Those who are governed, they’re the ones who have the power. Whatever kind of state it is, militaristic or more democratic, as England was becoming. The masters rule only by consent. And if consent is withdrawn, they lose. Their rule is very fragile.

I should say that today’s masters of the universe, as they modestly call themselves, understand this very well. Every January in Davos, the Switzerland ski resort, the great and powerful gather to go skiing, enjoy themselves, and congratulate each other on how wonderful they are. Top CEOs and media figures and entertainment figures and so on.

But this year was different. The theme was different. The theme was: We’re in trouble. The peasants are coming with their pitchforks. As they would prefer to put it, we’re facing “reputational risks.” They’re coming after us. Our control is fragile. We have to provide a different message. So the message at Davos was: Yes, we realize we’ve done wrong things during this whole neoliberal period. You, the general population, have suffered. We understand that. We’re overcoming our mistakes. We’re now going to be committed to you, the stakeholders and working-class communities, we’re really committed to your welfare. We’re becoming deeply humanitarian. We regret our mistakes. You can put your faith in us. We’ll take over and work for your benefit.

Do you think people are seeing through that neoliberal two-step of making money at the expense of the community and donating table scraps to the people they’ve hurt?

There’s a split. There are some who see through it. There’s some caught up in it. Take the United States. Maybe the greatest social movement to develop in American history, the Black Lives Matter-inspired movement. It’s all over the place. Has the kind of public support that no activist movement ever had. Martin Luther King, at the peak of his popularity, had never reached two-thirds public support for what he was doing. That reflects something.

Can you say why you think that is? Why has it succeeded at being such a persuasive movement?

Because of the changes in consciousness that have taken place over the past several years. They manifest themselves in many ways.

They manifest themselves in the climate strike last year, for example. Mostly young people, very dedicated. The Sunrise Movement succeeded. Got to the point of occupying congressional offices. Getting the support of a couple of the young congressional representatives who came in on the Sanders wave, especially Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Picked up support from Ed Markey, Massachusetts senator who’s been deeply concerned with the environment. Managed to put the Green New Deal on the legislative agenda.

It’s not a small point. We can debate what form it should take, but some form of Green New Deal is absolutely essential for the survival of organized human society. That’s part of it. There are many other things.

Right now, for example, Senator Tom Cotton is pushing legislation to remove federal aid from any school that makes use of The New York Times‘ 1619 series, the series which seriously reviewed the 400 years of vicious repression of Black Americans. The fact that that series appeared is already a great substantial sign of the change in awareness and consciousness. Couple of years ago, that would’ve been inconceivable. Now it’s getting to the point where the right wing wants to make sure to crush the threat of civilized society before it grows.

How do you think the left could do a better job in terms of the language it uses, the political appeals it makes, at reaching a broader group of people who are not hardcore? It often feels like Republicans are very gifted at making people vote for things that are not good for them and Democrats struggle to make people vote for things that would be very, very good for them.

Well, actually, the Sanders movement was remarkably successful. And it’s something that has broken with over 100 years of American political history. To bring a candidate to near nomination without any support from the media, from big donors, from the corporate sector. Nothing like that’s happened before. Could it do more? I think so.

Not to make a big fuss about it, but I’ve been mildly critical of Sanders’ presenting himself as a socialist. He’s not a socialist in my opinion. He’s a New Deal Democrat. A mild social democrat. His policies would not have surprised Eisenhower very much. It’s a sign of the shift to the right, of both parties, during the neoliberal period, that his positions are considered revolutionary.

What’s the point of calling himself socialist? That’s a scary word in the United States. The U.S. is an unusual society. In every other country in the world, a socialist is kind of like a Democrat. Somebody’s a socialist, fine. You can be a communist and be right in the political system. The United States is an extreme, business-run society with a very rigid set of controls. So words like socialist are scare words. Means the gulag. Communist, you can’t even mention.

All right, those are realities about the United States. We should do something about them. But you’re not going to unravel them in time for an election, OK? So, in my view, it’s a dubious stand to take.

You mentioned the 1619 Project. One of the things that it seems to bring out in its detractors is this fear that, if you tell the truth about the origins of the country and 400 years of repression, you’re stealing the grounds for their patriotism. You’re taking away their sense that their country is right and good.

You have advocated for so long for a brutal honesty about the United States, about empire, about how capitalism works. I wonder, how do you think about having an honest view about your country and still finding love for your country?

Depends which America you’re talking about.

Are you talking about John Calhoun? Talking about the people who instigated the most vicious system of slavery in human history? Is that the United States? Or are you talking about the abolitionists?

Are you talking about Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party, which regarded wage labor as different from slavery only in that it was temporary, because being dependent on another person is an intolerable attack on human rights and dignity? That’s one America. The other America is the robber barons, the slave owners, the people who destroyed Tulsa when a Black community was successful.

In the 1980s, there were the Reaganites who wanted to devastate and destroy and murder and slaughter in central America, who supported Apartheid until the last second. That’s one America. There’s another America of the people who dedicated themselves to go help and support the victims of our atrocities.

There’s the SNCC workers, and there’s Bull Connor.

There’s two different Americas. So which one do you want?

Over the last couple years, I’ve traveled around the country a lot and met a lot of people who agree with you about the need for big, structural transformation. But many also feel impatient, like “What can I do tomorrow?” These are people who recognize that there are no personal solutions, there are only political solutions. But they want to do something now. What do you say to people who are with you on the need to address these issues at the deepest level, but desire some kind of immediate way of getting involved?

Well, we have no shortage of immediate ways of getting involved. But immediate changes are another story. There’s kind of an instant gratification culture. I worked for Bernie Sanders, he didn’t win. I’m going home. That’s not the way political change takes place. It takes place step by step, small changes to bigger ones, and so on.

The absence of a continued left tradition in the United States is very harmful in this respect. Everything starts new. Things begin, they’re important, they dissipate.

Serious organizers in poor communities understand that the first thing they have to do is break through the sense of hopelessness. And there are ways of doing that.

Take the antiwar movement, Vietnam. I myself got involved in it in 1961, when Kennedy started escalating the war. Nobody was interested. It looked totally hopeless. The first talks that were given were literally in somebody’s living room. Couple of neighbors. Or a church with half a dozen people.

Within a couple of years, there was a mass popular movement. Way too late, but it did develop, and it had an impact. It’s very possible, as Dan Ellsberg and others have argued, that it prevented Nixon from using nuclear weapons. That’s how things change.

When you look at a centrist, neoliberal Democrat like Joe Biden, with the platform that you talked about, starting the campaign by saying that, under him, nothing fundamentally would change for the plutocrats, is your understanding of a person like that that they do not want to make these kinds of changes, they don’t want America to work in the ways you’re describing? Or that they have a kind of cautious realism about what is possible?

I’m not much interested in his personality. I don’t have any opinion. I’m interested in how things get done. And the way things get done is not by Biden having a religious conversion and saying, “Oh, we’ve got to really work on the climate.” That’s not what happened. The DNC probably hates the program, but they have no choice, because their popular base is not only demanding it, but is working constantly, hard, to force them to do it. That’s politics. Not the personality of leaders. I don’t know what’s in his mind. I don’t care, frankly.

You’re perhaps most known for this phrase “manufacturing consent,” which was about mass media. As you’ve watched the rise of social media, I wonder how you think social media has altered the power equations of the country. In what ways do you see it diffusing power? In what ways has it concentrated power further?

Social media, like most technologies, are pretty neutral. What matters is how you use them. You can use a hammer to build a house; you can use a hammer to smash somebody’s head in.

Social media are being used in very different ways. They’re used to organize activists, set up demonstrations, to give people the opportunity to interact, think, develop opinions, deliberate. But they can also be used to drive people into bubbles in which you hear only the same thing over and over. Your prejudices get reinforced, and you hate everybody else. They can be used either way. And they are being used both ways.

So the question comes back to us: How are we going to use the technology that’s available? It doesn’t care. We can use it any way we like. The net effect of social media probably, by and large, I suspect, has been mostly negative. Doesn’t have to be, but I think that’s the way it’s turned out.

So, for example, a lot of young people now get their news from Facebook. What’s Facebook giving you? Facebook doesn’t have reporters in the field.

The book Manufacturing Consent, which you mentioned, has often been misunderstood. It’s not saying the media don’t tell you the truth. In fact, much of the book is devoted to defense of the media. Reporters tell the truth. They’re serious, they’re courageous, they’re honest. They do it within a framework which restricts and constrains and shapes what they’re doing. But if you want to know what’s going on in the world, it’s much better to read The New York Times in the morning than to look at what filters its way down to Facebook.

Because of the pandemic and the related crises, the issues you have spent your life talking about are really at the fore of the discourse today. They’re in politics; they’re in activism; they’re unavoidable.

I know it’s probably not the kind of question you love, but I wonder about how you think about your legacy — what you feel you’ve tried to do and where you think we are.

I don’t really think about a legacy. What I’m interested in is the people who are doing things. Mostly their names will never be known. I’m sure you can’t tell me, or I can’t tell you, the names of the kids who sat in at the lunch counter in Greensboro. These are the people who carry things forward. If there’s a legacy of people who try to do what they can to stimulate it, it’s theirs. The ones I most respect in the world, I can’t remember their names. People in refugee camps in Laos. The peasants in southern Colombia trying to stave off paramilitary attacks and protect themselves from corporations that want to destroy their water supply with gold mines. People in Kurdish areas in Turkey.

I’ll give you an example. At the peak of the Turkish repression of the Kurds, it was very vicious. It was worst in the 1990s. It was strongly supported by Clinton. He was pouring arms in the worse the oppression got. I happened to be there at the tail end of it. I gave a talk.

You were not allowed to speak Kurdish. It was a crime. You could disappear and never be seen again. I was cautious in the talk not to arouse too much ire of the security people.

At the end of my talk, four kids came up holding a big book and gave it to me. It was a Kurdish-Turkish dictionary. They were saying, “We’re going to struggle on.” I don’t know what happened to them. But it’s people like that all over the world whom you can really respect. They’re the ones who matter for any legacy that emerges.

Noam Chomsky is a laureate professor in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Arizona and professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he taught for more than 50 years.

For subscribers: if you’d like to read the full interview, and Anand’s other conversation with Noam Chomsky, focusing on the fight against fascism and his hopes for the future, just click on the links below.

Your support makes The Ink possible. We’d be honored if you’d become a paid subscriber. When you do, you’ll get access each week to our regular posts and our interviews with the most thoughtful people out there — and you’ll be able to join the conversation in our comments section.

Get 20% off forever

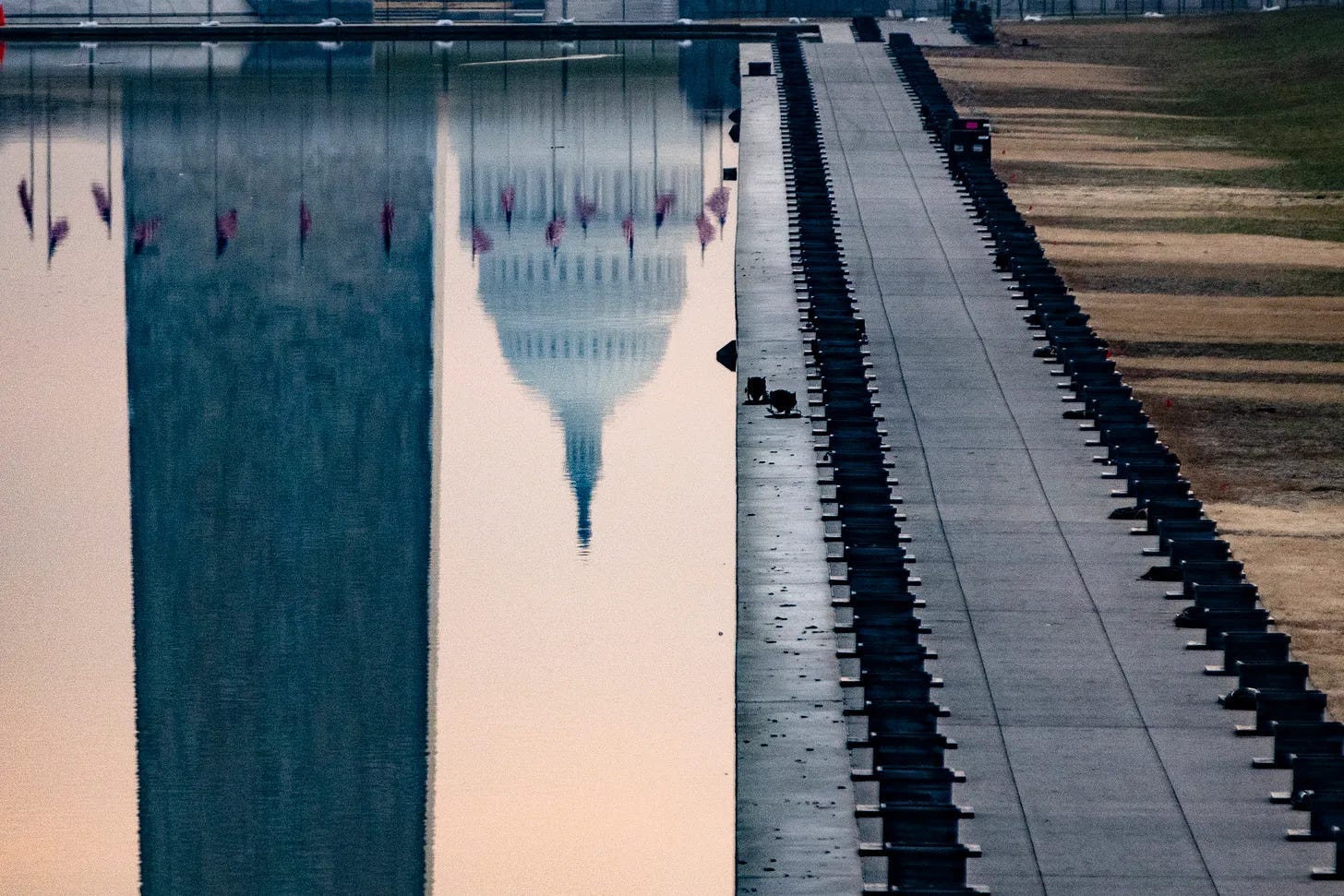

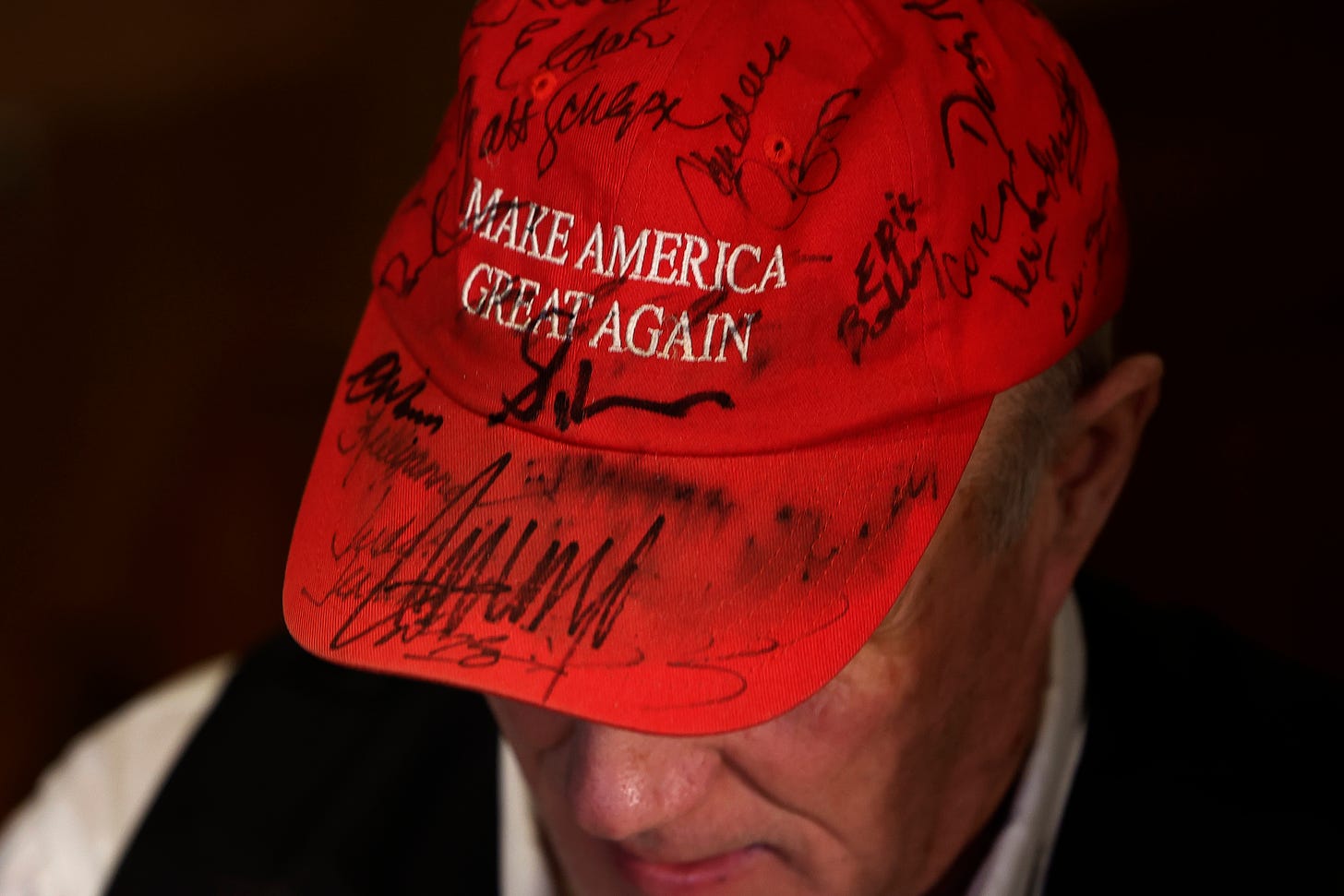

Photo credit: Heuler Andrey/Getty

This post was originally published on The.Ink.