For Comrade N. Sankaraiah (1922–2023)

For Comrade N. Sankaraiah (1922–2023)

One of the curiosities of our time is that the far right is quite comfortable with the established institutions of liberal democracy. There are instances here and there of disgruntled political leaders who refuse to accept their defeat at the ballot box (such as Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro) and then call upon their supporters to take extra-parliamentary action (as on 6 January 2021 in the United States and, in a farcical repetition, on 8 January 2023 in Brazil). But, by and large, the far right knows that it can attain what it wants through the institutions of liberal democracy, which are not hostile to its programmes.

The fatal, intimate embrace between the political projects of liberalism and those of the far right can be understood in two ways. First, this embrace is seen in the ease with which the forces of the far right use their countries’ liberal constitutions and institutions to their benefit, without any need to supplant them dramatically. If a far-right government can interpret a liberal constitution in this way, and if the institutions and personnel of this constitutional structure are not averse to this interpretation by the far right, then there is no need for a coup against the liberal structure. It can be hollowed from within.

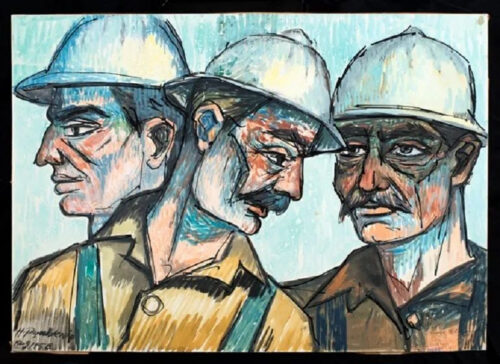

Second, this intimate, but fatal, embrace takes place within the ‘cultures of cruelty’ (as Aijaz Ahmad called it) that define the social world of savage capitalism. Forced to work for capital – in increasingly precarious and atomised jobs – to survive, workers discover, as Karl Marx astutely observed in 1857/58, that it is money that is the ‘real community’ (Gemeinwesen) and it is the person who is the instrument, and the slave, of money. Wrenched from the care of genuine community, workers are forced into lives that oscillate between the hell of long and difficult workdays and the purgatory of long and difficult unemployment. The absence of state-provided social welfare and the collapse of worker-led community institutions produce ‘cultures of cruelty’, a normal kind of violence that runs from within the home to out on the streets. This violence often takes place without fanfare and reinforces traditional structures of power (along axes of patriarchy and of nativism, for instance). The far right’s source of power lies in these ‘cultures of cruelty’, which occasionally lead to spectacular acts of violence against social minorities. Savage capitalism has globalised production and liberated property owners (both individuals and corporations) from adhering to even the norms of liberal democracy, such as paying their fair share of taxes. This political economic structure of savage capitalism generates a neoliberal social order that is rooted in imposing austerity on the working class and the peasantry and in atomising working people by increasing their working time, eroding the social institutions that they run, and, therefore, diminishing their leisure time. Liberal democracies around the world conduct time-use surveys of their populations to see how people spend their time, but almost none of these surveys pay attention to whether workers and peasants have any time for leisure, how they might spend this leisure time, and whether the reduction of their leisure time is a concern for general social development in their country. We are very far away from the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation’s 1945 Constitution that urged the ‘free flow of ideas by word and image’ and the need to ‘give fresh impulse to popular education and to the spread of culture’. Social discussions about the dilemmas of humanity are silenced while old forms of hatred are sanctioned.

Savage capitalism has globalised production and liberated property owners (both individuals and corporations) from adhering to even the norms of liberal democracy, such as paying their fair share of taxes. This political economic structure of savage capitalism generates a neoliberal social order that is rooted in imposing austerity on the working class and the peasantry and in atomising working people by increasing their working time, eroding the social institutions that they run, and, therefore, diminishing their leisure time. Liberal democracies around the world conduct time-use surveys of their populations to see how people spend their time, but almost none of these surveys pay attention to whether workers and peasants have any time for leisure, how they might spend this leisure time, and whether the reduction of their leisure time is a concern for general social development in their country. We are very far away from the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation’s 1945 Constitution that urged the ‘free flow of ideas by word and image’ and the need to ‘give fresh impulse to popular education and to the spread of culture’. Social discussions about the dilemmas of humanity are silenced while old forms of hatred are sanctioned.

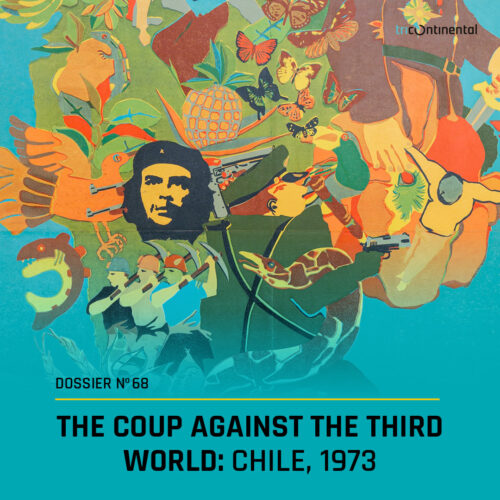

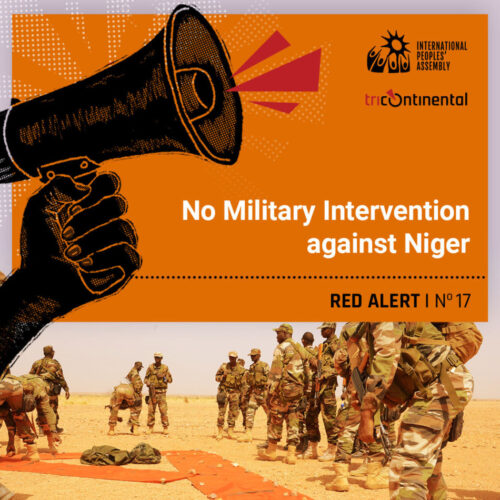

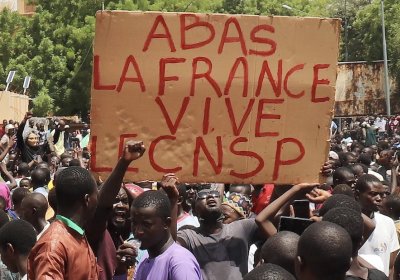

It is the hatred of the migrant, the terrorist, and the drug dealer – all portrayed as sociopaths – that evokes an acerbic form of nationalism, one that is not rooted in love of one’s fellow human beings but in hatred of the outsider. Hatred masquerades as patriotism while the size of the national flag grows and the enthusiasm for the national anthem increases by decibels. This is visibly displayed in Israel today. This neoliberal, savage, far-right patriotism smells acrid – of anger and bitterness, of violence and frustration. In cultures of cruelty, people’s eyes are turned away from their own problems, from the low wages and near starvation in their homes, from their lack of educational opportunities and provisions for health care, to other – false – problems that are invented by the forces of savage capitalism to turn people away from their real problems. It is one thing to be patriotic against starvation and hopelessness. But the forces of savage capitalism have taken this form of patriotism and thrown it into the fire. Human beings ache to be decent, which is why so many billions across the world have taken to the streets, blocked boats, and occupied buildings to demand an end to Israel’s war on Gaza. But that ache is smothered by desperation and resentment, by the intimate, diabolical embrace of liberalism and the far right. From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes What Can We Expect from the New Progressive Wave in Latin America? (dossier no. 70, November 2023), a study of the political landscape in Latin America. The text opens with a foreword by Daniel Jadue (the mayor of the commune of Recoleta, Santiago de Chile, and a leading member of the Communist Party of Chile). Jadue argues that savage capitalism has sharpened the contradictions between capital and labour and has accelerated the destruction of the planet. The ‘political centre’, he argues, has governed most countries in the world for the past few decades ‘without resolving the most pressing issues of the people’. With social democratic forces moving to defend savage capitalism and neoliberal austerity, the left has been dragged to the centre to defend the institutions of democracy and the structures of social welfare. Meanwhile, there has been, Jadue writes, ‘the resurgence of highly combative discourse among right-wing forces that is even more extreme than in the era of fascism almost a century ago’.

From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes What Can We Expect from the New Progressive Wave in Latin America? (dossier no. 70, November 2023), a study of the political landscape in Latin America. The text opens with a foreword by Daniel Jadue (the mayor of the commune of Recoleta, Santiago de Chile, and a leading member of the Communist Party of Chile). Jadue argues that savage capitalism has sharpened the contradictions between capital and labour and has accelerated the destruction of the planet. The ‘political centre’, he argues, has governed most countries in the world for the past few decades ‘without resolving the most pressing issues of the people’. With social democratic forces moving to defend savage capitalism and neoliberal austerity, the left has been dragged to the centre to defend the institutions of democracy and the structures of social welfare. Meanwhile, there has been, Jadue writes, ‘the resurgence of highly combative discourse among right-wing forces that is even more extreme than in the era of fascism almost a century ago’.

Our dossier traces the zigs and zags of politics across Latin America, with the left’s triumph in Colombia’s presidential election balanced out by the tight grip of the right in Peru, then settling on a point that is of great importance: the left across most of Latin America has abandoned the final aim of socialism and has instead adopted the task of being managers of capitalism with a more human face. As the dossier states:

[T]he left today has shown itself to be incapable of achieving hegemony when it comes to a new societal project. The irrevocable defence of bourgeois democracy itself is a symptom that there is no prospect of rupture and revolution. This is reflected by the reluctance of certain left‐wing leaders to support the current Venezuelan government, which they consider to be undemocratic – despite the fact that Venezuela, alongside Cuba, is one of the few examples of a country where the left has managed to face these crises without being defeated. This meek position and failure to commit to the fight against imperialism marks a significant setback. Liberal democracy has proved itself to be an insufficient barrier to halt the ambitions of the far right. Though liberal elites are horrified by the vulgarity of the far right, they are not necessarily opposed to diverting the masses from a politics of class to a politics of despair, as the far right has done. The main criticism of the right does not come from liberal institutions, but from the fields and the factories, as seen in the mobilisations against hunger and against the uberisation of work. From the mass demonstrations against austerity and for peace in Colombia (2019–2021) to those against lawfare in Guatemala (2023), people – barricaded, for decades, from liberal institutions – have again taken to the streets. Electoral victories are important, but, alone, they transform neither society nor political control, which has remained under the tight grip of the elite in most of the world.

Liberal democracy has proved itself to be an insufficient barrier to halt the ambitions of the far right. Though liberal elites are horrified by the vulgarity of the far right, they are not necessarily opposed to diverting the masses from a politics of class to a politics of despair, as the far right has done. The main criticism of the right does not come from liberal institutions, but from the fields and the factories, as seen in the mobilisations against hunger and against the uberisation of work. From the mass demonstrations against austerity and for peace in Colombia (2019–2021) to those against lawfare in Guatemala (2023), people – barricaded, for decades, from liberal institutions – have again taken to the streets. Electoral victories are important, but, alone, they transform neither society nor political control, which has remained under the tight grip of the elite in most of the world.

Jadue’s foreword is alert to both the weakness of the political centre and the necessity to build a political project that lifts up mobilisations and prevents them from dissipating into frustration:

Reconstructing a concrete horizon – socialism – and building the unity of the left are key challenges in identifying and addressing the dilemmas we face. In order to do this, we must break from the language of our oppressors and create one that is truly emancipatory. Integration and coordination are no longer enough. A true understanding of what Karl Marx called the material unity of the world is essential to achieving the total unity of peoples and joint action across the planet.

The reservoirs of working-class forces across the world – including precarious workers and the peasantry – have been depleted by the process of globalisation. Leading revolutionary parties have found it difficult to extend and even maintain their strength in the context of democratic systems that have been taken over by the power of money. Nevertheless, to face these challenges, the ‘concrete horizon’ of socialism that Jadue mentions is being crafted through the sustained building of organisations, through the mobilisation of the masses, and through political education, including the battle of ideas and the battle of emotions (part of which, of course, is the work of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and this new dossier, which we hope that you will read and circulate for discussion).

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.