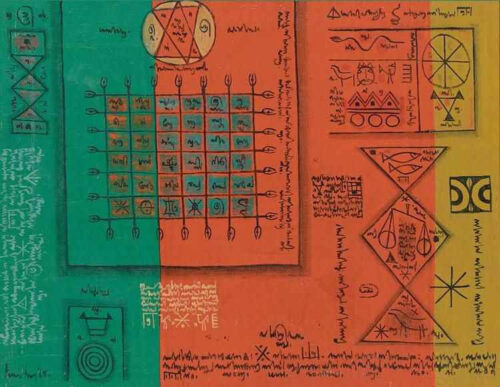

Spiridonov Yuri Vasilyevich (Sakha), Landlord of the Moma Mountains, 2006.

In 1996, the eight countries on the Arctic rim – Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States – formed the Arctic Council, a journey that began in 1989 when Finland approached the other countries to hold a discussion about the Arctic environment. The Finnish initiative led to the Rovaniemi Declaration (1991), which established the council’s precursor, the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy.

The main concern for these governments at the time was the impact of ‘global pollution and resulting environmental threats’ to the Arctic, which was destroying the region’s ecosystem. There was little understanding of the scale and implications of the polar ice cap melting (consensus about that danger was amplified by the research of scientists such as Xiangdong Zhang and John Walsh in 2006 and the Fourth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007). The Arctic Council’s remit was later expanded to include investigations on climate change and development in the region.

More recently, at the 2021 ministerial meeting of the Arctic Council in Reykjavík (Iceland), Russia took over as the organisation’s rotating two-year chair. However, on 3 March 2022 – exactly one week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – the other council members began to boycott meetings in protest of Moscow’s involvement in the group. In June 2022, these seven countries agreed to ‘implement a limited resumption of our work in the Arctic Council on projects that do not involve the participation of the Russian Federation’. In essence, the council’s future is at stake.

Andreas Alariesto (Sápmi), Away, Bad Spirit, 1976.

Yet, geopolitical tensions in the Arctic did not begin last year. They have been simmering for more than a decade as these eight countries have jockeyed for control over the area – not to stem the dangers of climate change, but to exploit the vast deposits of minerals, metals, and fossil fuels that are present within the 21 million square kilometres of the Arctic Circle. The region is estimated to contain 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and natural gas (although extraction from this region remains expensive). Far more lucrative is the mining of rare earth minerals (such as neodymium for capacitors and electric motors and terbium for magnets and lasers), whose value across the Arctic – from Greenland’s Kvanefjeld to Russia’s Kola Peninsula to the Canadian Shield – is estimated to be at least one trillion dollars. Each member of the Arctic Council is racing to establish control over these precious resources, which, until now, have been locked beneath the melting ice.

Because more than half of the Arctic is made up of international waters and the continental shelves of these eight countries (i.e., landmass that extends into shallow ocean waters), its regulation largely falls under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which is ratified by 168 parties. According to the UNCLOS, the sovereignty of a coastal state extends to its territorial sea, defined as the area within 12 nautical miles from the low-water line of their coast. States also have the right to create an ‘exclusive economic zone’ within 200 nautical miles of that low-water mark, where many of these resources are located. As a result, exploitation of the Arctic’s resources is mainly the domain of the council’s member states and is largely outside of multilateral control. However, the UNCLOS does constrain individual state sovereignty by declaring that the deep seabed is the ‘common heritage’ of humanity and its exploration and exploitation ‘shall be carried out for the benefits of mankind as a whole, irrespective of the geographical location of States’.

Lucy Qinnuayuak (Kinngait), Children Followed by Bird Spirit, 1967.

The UN created the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to implement the UNCLOS treaty. In Kingston (Jamaica), the ISA’s legal and technical commission is developing a mining code to regulate exploration and exploitation of the international seabed area. It is worth noting that one fifth of the commission’s members are from mining companies. While there is no possibility of enacting a global moratorium on deep-sea mining – even in the Arctic, despite the 1959 Antarctic Treaty effectively banning mining on that continent – a mining code that favours mining companies will not only increase exploitation, but also increase competition and the risk of conflict between major powers. This competition has already intensified the New Cold War between North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) states – led by the US – and countries such as China and Russia and has led to the rapid militarisation of the Arctic.

Every member of the Arctic Council has already created military bases on the Arctic rim, with the race to dominate the region accelerating after 2007, when Russian scientists symbolically placed a titanium flag on the Arctic seabed, 4,302 metres below the North Pole. Artur Chilingarov, the Russian explorer who led this geographical expedition, said that he was motivated by science and a concern for climate change and that ‘the Arctic must be protected not in words, but in deeds’. Nonetheless, the Russian geological expedition was used as a pretext to expand militarisation in the region. For decades, the US has had a military presence deep inside the Arctic Circle, the Thule Air Base in Greenland, which it developed in the 1950s after Denmark – the colonial ruler over Greenland – joined NATO. Other Arctic littoral countries, too, have long had military forces that traverse the ice and snows of the north, a presence that has grown in recent years. Canada, for instance, is building the Nanisivik Naval Facility on Baffin Island, Nunavut, aiming for it to be operational in 2023. Meanwhile, over the past decade, Russia has renovated the Nagurskoye air base in Alexandra Land and the Temp air base on Kotelny Island.

Sivtsev Ellay Semenovitch (USSR), On the Bull, 1963.

The Arctic Council was one of the few multilateral institutions to facilitate communication between the powers in the region. Now, seven of them have decided to no longer participate. Five of these abstaining members (Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and the US) are already part of NATO, while the remaining two (Finland and Sweden) are being fast-tracked into the organisation. Increasingly, NATO is replacing the Arctic Council as a decision-making authority in the region, with its operations based out of the Centre of Excellence for Cold Weather Operations in Norway. Since 2006, this hub has brought together NATO allies and partners for biannual military exercises in the Arctic called Cold Response.

In May 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went to the Arctic Council meeting in Rovaniemi (Finland) and accused China of being responsible for environmental destruction in the Arctic. Although China has launched a Polar Silk Road project, there is no real evidence that China has played a particularly deleterious role in the northern sea lanes. This hostile comment towards China and similar sentiments about Russia’s role in the Arctic are part of the ideological battle to justify the New Cold War. Less than a month after Pompeo’s speech, the US Department of Defence released its Arctic Strategy (2019), which focused on ‘limiting the ability of China and Russia to leverage the region as a corridor for competition’ (a mood repeated in the US Air Force’s 2020 Arctic Strategy).

Per Enoksson (Sápmi), Sing, Sing, Sing-along Song, 2008–2010.

In October 2022, Reykjavík hosted its annual Arctic Circle gathering, attended by all of the major powers, except Russia, which was not invited. Iceland’s former President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, who was embroiled in the 2016 Panama Papers corruption scandal, chaired the keynote speech given by the Dutch Admiral Rob Bauer, chairman of the NATO Military Committee. Bauer said that NATO must have a more muscular presence in the Arctic in order to check Russia as well as China, which he called ‘another authoritarian regime that does not share our values and undermines the rules-based international order’. China’s Polar Silk Road, Admiral Bauer said, is merely a shield behind which Chinese ‘naval formations could move more quickly from the Pacific to the Atlantic, and submarines could shelter in the Arctic’.

During the discussion period, China’s ambassador to Iceland, He Rulong, rose from his seat to say to the NATO admiral, ‘Your speech and remark are full of arrogance and also paranoid. The Arctic region is an area for high cooperation and low confrontation… The Arctic plays an important role when it comes to climate change… Every country should be part of this process’. China, he continued, should not be ‘singled out [from] the cooperation’. Grímsson closed the session after He’s intervention to muted laughter in the hall.

Maria Petrovna Vyucheyskaya (USSR), Going to a Demonstration, 1932–1933.

Absent from most of these discussions are the indigenous communities who live in the Arctic: the Aleut and Yupik (United States); the Inuit (Canada, Greenland, and the United States); the Chukchi, Evenk, Khanty, Nenets, and Sakha (Russia); and the Saami (Finland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden). Though these communities are represented by six organisations on the Arctic Council – the Aleut International Association, the Arctic Athabaskan Council, the Gwich’in Council, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, and the Russian Association of Indigenous People of the North, and the Saami Council – their voices have been further muted during the intensified conflict.

This silencing of indigenous voices reminds me of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (1943–2001), the great Saami artist, whose poetry rattles like the sound of the wind:

Can you hear the sounds of life

in the roaring of the creek

in the blowing of the wind

That is all I want to say

that is all

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

On January 3, 2023, Shaun Tandon of Agence France-Presse asked U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price about Venezuela. In late December, the Venezuelan opposition after a fractious debate decided to dissolve the “interim government” led by Juan Guaidó. From 2019 onward, the U.S. government recognized Guaidó as the “interim president of Venezuela.” With the end of Guaidó’s administration, Tandon asked if “the United States still recognize[s] Juan Guaidó as legitimate interim president.” More

The post Which Government Does the United States Recognize in Venezuela? appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

The answers for South Africa will have to come from struggle, National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) leader Irvin Jim tells Vijay Prashad and Zoe Alexandra.

Philip Guston (Canada), Gladiators, 1940.

In May 2021, the executive director of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, and the UN high representative for disarmament affairs, Izumi Nakamitsu, wrote an article urging governments to cut excessive military spending in favour of increasing spending on social and economic development. Their wise words were not heard at all. To cut money for war and to increase money for social development, they wrote, is ‘not a utopian ideal, but an achievable necessity’. That phrase – not a utopian ideal, but an achievable necessity – is essential. It describes the project of socialism almost perfectly.

Our institute has been at work for over five years, driven precisely by this idea that it is possible to transform the world to meet the needs of humanity while living within nature’s limits. We have accompanied social and political movements, listened to their theories, observed their work, and built our own understanding of the world based on these attempts to change it. This process has been illuminating. It has taught us that it is not enough to try and build a theory from older theories, but that it is necessary to engage with the world, to acknowledge that those who are trying to change the world are able to develop the shards of an assessment of the world, and that our task – as researchers of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research – is to build those shards into a worldview. The worldview that we are developing does not merely understand the world as it is; it also takes hold of the dynamic that seeks to produce the world as it should be.

Marcelo Pogolotti (Cuba), Siglo XX o Regalo a la querida (‘20th century or Gift for the loved one’), 1933.

Our institute is committed to tracing the dynamics of social transcendence, and how we can get out of a world system that is driving us to annihilation and extinction. There are sufficient answers that exist in the world now, already present with us even when social transformation seems impossible. The total social wealth on the planet is extraordinary, although – due to the long history of colonialism and violence – this wealth is simply not used to generate solutions for common problems, but to aggrandise the fortunes of the few. There is enough food to feed every person on the planet, for instance, and yet billions of people remain hungry. There is no need to be naïve about this reality, nor is there a need to feel futile.

In one of our earliest newsletters, which brought our first year of work (2018) to a close, we wrote that ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the earth than to imagine the end of capitalism, to imagine the polar ice cap flooding us into extinction than to imagine a world where our productive capacity enriches all of us’. This remains true. And yet, despite this, there is ‘a possible future that is built to meet people’s aspirations. … It is cruel to think of these hopes as naïve’.

The problems we face are not for lack of resources or lack of technological and scientific knowhow. At Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, we believe that it is because of the social system of capitalism that we are unable to transcend our common problems. This system constrains the forward movement that requires the democratisation of nations and the democratisation of social wealth. There are hundreds of millions of people organised into political and social formations that are pushing against the gated communities in our world, fighting to break down the barriers and build the utopias that we require to survive. But, rather than recognise that these formations seek to realise genuine democracy, they are criminalised, their leaders arrested and assassinated, and their own precious social confidence vanquished. Much the same repressive behaviour is meted out to national projects that are rooted in such political and social movements, projects that are committed to using social wealth for the greatest good. Coups, assassinations, and sanctions regimes are routine, their frequency illustrated by an unending sequence of events, from the coup in Peru in December 2022 to the ongoing blockade of Cuba, and by the denial that such violence is used to block social progress.

Renato Guttuso (Italy), May 1968, 1968.

In his introduction to philosophy in 1997, the German Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch wrote, ‘I am. But I don’t have myself. And only therefore we become’. This is an interesting statement. Bloch is reformulating René Descartes’ ‘I think, therefore I am’, an idealist proposition. Bloch affirms existence (‘I am’), but then suggests that human existence does not flourish due to forms of alienation and loneliness (‘But I don’t have myself’). The ‘I’ – the atomised, fragmented, and lonely individual – does not have the capacity to change the world alone. To build a process towards social transcendence requires the creation of a collective ‘we’. This collective is the subjective force that must strengthen itself to overpower the contradictions that stand in the way of human progress. ‘To be Human means in reality to have Utopia’, Bloch wrote. This phrase resonates deeply with me, and I hope that it touches you, too.

In the new year, we at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will reflect at length on the pathways to socialism and the barricades that seek to prevent the world’s billions from going beyond a system that extracts their social labour and promises greatness while delivering the barest minimum of life’s possibilities. We walk into this new year with a renewed commitment to the simple postulate, socialism is an achievable necessity.

Milan Chovanec (Czechoslovakia), Peace, 1978.

As we begin the new year, I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who works at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, a team that is spread across the globe, from Buenos Aires to Shanghai, from Trivandrum to Rabat. If you would like to assist our work, please remember that we welcome donations.

We urge you to share our materials as widely as possible, to study them in your movements, and to invite members of our team to speak about our work.

The post Socialism Is Not a Utopian Ideal, but an Achievable Necessity first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

Pathy Tshindele (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Untitled, 2016.

The United States government held the US-Africa Leaders Summit in mid-December, prompted in large part by its fears about Chinese and Russian influence on the African continent. Rather than routine diplomacy, Washington’s approach in the summit was guided by its broader New Cold War agenda, in which a growing focus of the US has been to disrupt relations that African nations hold with China and Russia. This hawkish stance is driven by US military planners, who view Africa as ‘NATO’s southern flank’ and consider China and Russia to be ‘near-peer threats’. At the summit, US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin charged China and Russia with ‘destabilising’ Africa. Austin provided little evidence to support his accusations, apart from pointing to China’s substantial investments, trade, and infrastructure projects with many countries on the continent and maligning the presence in a handful of countries of several hundred mercenaries from the Russian private security firm, the Wagner Group.

The African heads of government left Washington with a promise from US President Joe Biden to make a continent-wide tour, a pledge that the United States will spend $55 billion in investments, and a high-minded but empty statement on US-Africa partnership. Unfortunately, given the US track record on the continent, until these words are backed up with constructive actions, they can only be considered empty gestures and geopolitical jockeying.

There was not one word in the summit’s final statement on the most pressing issue for the continent’s governments: the long-term debt crisis. The 2022 UN Conference on Trade and Development Report found that ‘60% of least developed and other low-income countries were at high risk of or already suffering in debt distress’, with sixteen African countries at high risk and another seven countries – Chad, Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, Somalia, Sudan, and Zimbabwe – already in debt distress. On top of this, thirty-three African countries are in dire need of external assistance for food, which exacerbates the already existing risk of social collapse. Most of the US-Africa Leaders Summit was spent pontificating on the abstract idea of democracy, with Biden farcically taking aside heads of state like President Muhammadu Buhari (Nigeria) and President Félix Tshisekedi (Democratic Republic of Congo) to lecture them on the need for ‘free, fair, and transparent’ elections in their countries while pledging to provide $165 million to ‘support elections and good governance’ in Africa in 2023.

Chéri Samba (DRC), Une vie non raté (‘A Successful Life’), 1995.

Most of the debt held by the African states is owed to wealthy bondholders in the Western states and was brokered by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These private creditors – who hold the debt of countries such as Ghana and Zambia – have refused to provide any debt relief to African states despite the great distress they are experiencing. Often left out of conversations about this issue is the fact that this long-term debt distress has been largely caused by the plunder of the continent’s wealth.

On the other hand, unlike the wealthy bondholders of the West, the largest government creditor to African states, China, decided in August 2022 to cancel twenty-three interest-free loans to seventeen countries and offer $10 billion of its IMF reserves for use by the African states. A fair and rational approach to the debt crisis on the African continent would suggest that much more of the debt owed to Western bondholders should be forgiven and that the IMF should allocate Special Drawing Rights to provide liquidity to countries suffering from the endemic debt crisis. None of this was on the agenda of the US-Africa Leaders Summit.

Instead, Washington combined bonhomie towards the African heads of government with a sinister attitude towards China and Russia. Is this friendliness from the US a sincere olive branch or a trojan horse with which it seeks to smuggle its New Cold War agenda onto the continent? The most recent US government white paper on Africa, published in August 2022, suggests that it is the latter. The document, purportedly focused on Africa, featured ten mentions of China and Russia combined, but no mention of the term ‘sovereignty’. The paper stated:

In line with the 2022 National Defense Strategy, the Department of Defense will engage with African partners to expose and highlight the risks of negative PRC [People’s Republic of China] and Russian activities in Africa. We will leverage civil-defense institutions and expand defense cooperation with strategic partners that share our values and our will to foster global peace and stability.

The document reflects the fact that the US has conceded that it cannot compete with what China offers as a commercial partner and will resort to military power and diplomatic pressure to muscle the Chinese off the continent. The massive expansion of the US military presence in Africa since the 2007 founding of the United States Africa Command – most recently with a new base in Ghana and manoeuvres in Zambia – illustrates this approach.

Kura Shomali (DRC), Miss Panda, 2018.

The United States government has built a discourse to tarnish China’s reputation in Africa, which it characterises as ‘new colonialism’, as former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in a 2011 interview. Does this reflect reality? In 2017, the global corporate consulting firm McKinsey & Company published a major report on China’s role in Africa, noting after a full assessment, ‘On balance, we believe that China’s growing involvement is strongly positive for Africa’s economies, governments, and workers’. Evidence to support this conclusion includes the fact that since 2010, ‘a third of Africa’s power grid and infrastructure has been financed and constructed by Chinese state-owned companies’. In these Chinese-run projects, McKinsey found that ‘89 percent of employees were African, adding up to nearly 300,000 jobs for African workers’.

Certainly, there are many stresses and strains involved in these Chinese investments, including evidence of poor management and badly designed contracts, but these are neither unique to Chinese companies nor endemic to their approach. US accusations that China is practicing ‘debt trap diplomacy’ have also been widely debunked. The following observation, made in a 2007 report, remains insightful: ‘China is doing more to promote African development than any high-flying governance rhetoric’. This assessment is particularly noteworthy given that it came from the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, an intergovernmental bloc dominated by the G7 countries.

What will be the outcome of the United States’ recent $55 billion pledge to African states? Will the funds, which are largely earmarked for private firms, support African development or merely subsidise US multinational corporations that dominate food production and distribution systems as well as health systems in Africa?

Mega Mingiedi Tunga (DRC), Transactor Code Rouge, 2021.

Here’s a telling example of the emptiness and absurdity of the US’s attempts to reassert its influence on the African continent. In May 2022, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia signed a deal to independently develop electric batteries. Together, the two countries are home to 80 percent of the minerals and metals needed for the battery value chain. The project was backed by the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), whose representative Jean Luc Mastaki said, ‘Adding value to the battery minerals, through an inclusive and sustainable industrialisation, will definitely allow the two countries to pave the way to a robust, resilient, and inclusive growth pattern which creates jobs for millions of our population’. With an eye on increasing indigenous technical and scientific capacity, the agreement would have drawn from ‘a partnership between Congolese and Zambian schools of mines and polytechnics’.

Fast forward to the summit: after this agreement had already been reached, the DRC’s Foreign Minister Christophe Lutundula and Zambia’s Foreign Minister Stanley Kakubo joined US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in signing a memorandum of understanding that would allegedly ‘support’ the DRC and Zambia in creating an electric battery value chain. Lutundula called it ‘an important moment in the partnership between the US and Africa’.

The Socialist Party of Zambia responded with a strong statement: ‘The governments of Zambia and Congo have surrendered the copper and cobalt supply chain and production to American control. And with this capitulation, the hope of a Pan-African-owned and controlled electric car project is buried for generations to come’.

Pierre Bodo (DRC), Femme surchargée (‘Overworked Woman’), 2005.

It is with child labour, strangely called ‘artisanal mining’, that multinational corporations extract the raw materials to control electric battery production rather than allow these countries to process their own resources and make their own batteries. José Tshisungu wa Tshisungu of the Congo takes us to the heart of the sorrows of children in the DRC in his poem, ‘Inaudible’:

Listen to the lament of the orphan

Stamped with the seal of sincerity

He is a child from around here

The street is his home

The market his neighbourhood

The monotone of his plaintive voice

Runs from zone to zone

Inaudible.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

Reference photograph: Sandinistas at the Walls of the National Guard Headquarters: ‘Molotov Man’, Estelí, Nicaragua, July 16th, 1979, by Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

The International Labour Organisation’s Global Wage Report 2022–23 tracks the horrendous collapse of real wages for billions of people around the planet. The gaping distance between the incomes and wealth of 99% of the world’s population from the incomes and wealth of the billionaires and near-trillionaires who make up the richest 1% is appalling. During the pandemic, when most of the world has experienced a dramatic loss in their livelihoods, the ten richest men in the world have doubled their fortunes. This extreme wealth inequality, now entirely normal in our world, has produced immense and dangerous social consequences.

If you take a walk in any city on the planet, not just in the poorer nations, you will find larger and larger clusters of housing that are congested with destitution. They go by many names: bastis, bidonville, daldongneh, favelas, gecekondu, kampung kumuh, slums, and Sodom and Gomorrah. Here, billions of people struggle to survive in conditions that are unnecessary in our age of massive social wealth and innovative technology. But the near-trillionaires seize this social wealth and prolong their half-century tax strike against governments, which paralyses public finances and enforces permanent austerity on the working class. The constricting squeeze of austerity defines the world of the bastis and the favelas as people constantly struggle to overcome the obstinate realities of hunger and poverty, a near absence of drinking water and sewage systems, and a shameful lack of education and medical care. In these bidonvilles and slums, people are forced to create new forms of everyday survival and new forms of belief in a future for themselves on this planet.

Reference photograph: Neighbourhood residents and other guests participate in a popular bible study in Petrolina, in the state of Pernambuco, 2019. Sourced from the Popular Communication Centre (Brazil).

These forms of everyday survival can be seen in the self-help organisations – almost always run by women – that exist in the harshest environments, such as inside Africa’s largest slum, Kibera (Nairobi, Kenya), or in environments supported by governments with few resources, such as in Altos de Lídice Commune (Caracas, Venezuela). The Austerity State in the capitalist world has abandoned its elementary duty of relief, with non-governmental organisations and charities providing necessary but insufficient band-aids for societies under immense stress.

Not far from the charities and self-help organisations sit a persistent fixture in the planet of slums: gangs, the employment agencies of distress. These gangs assemble the most distressed elements of society – mostly men – to manage a range of illegal activities (drugs, sex trafficking, protection rackets, gambling). From Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl (Mexico City, Mexico) to Khayelitsha (Cape Town, South Africa) to Orangi Town (Karachi, Pakistan), the presence of impoverished thugs, from petty thieves or malandros to members of large-scale gangs, is ubiquitous. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the favelados (‘slum dwellers’) of Antares call the entrance of their neighbourhood bocas (‘mouths’), the mouths from which drugs can be bought and the mouths that are fed by the drug trade.

Reference photograph: Bishop Sérgio Arthur Braschi of the Diocese of Ponta Grossa (in the state of Paraná) blesses food that Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) donated to 500 families in need, 2021, by Jade Azevedo.

In this context of immense poverty and social fragmentation, people turn to different kinds of popular religions for relief. There are practical reasons for this turn, of course, since churches, mosques, and temples provide food and education as well as places for community gatherings and activities for children. Where the state mostly appears in the form of the police, the urban poor prefer to take refuge in charity organisations that are often connected in some way or another to religious orders. But these institutions do not draw people in only with hot meals or evening songs; there is a spiritual allure that should not be minimised.

Our researchers in Brazil have been studying the Pentecostal movement for the past few years, conducting ethnographic research across the country to understand the appeal of this rapidly growing denomination. Pentecostalism, a form of evangelical Christianity, emerged as a site of concern because it has begun to shape the consciousness of the urban poor and the working class in many countries with traditionalist ideas and has been key in efforts to transform these populations into the mass base of the New Right. Dossier no. 59, Religious Fundamentalism and Imperialism in Latin America: Action and Resistance (December 2022), researched and written by Delana Cristina Corazza and Angelica Tostes, synthesises the research of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research (Brazil) working group on evangelism, politics, and grassroots organising. The text charts the rise of the Pentecostal movement in the context of Latin America’s turn to neoliberalism and offers a granular analysis of why these new faith traditions have emerged and why they dovetail so elegantly with the sections of the New Right (including, in the Brazilian context, with the political fortunes of Jair Bolsonaro and the Bolsonaristas).

Reference photograph: Participants of a march and vigil organised by the Love Conquers Hate Christian Collective light candles during a prayer with believers of various faiths in Rio de Janeiro, 2018, by Gabriel Castilho.

In the 19th century, a very young Karl Marx captured the essence of religious desire amongst the downtrodden: ‘Religious suffering’, he wrote, ‘is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people’. It is erroneous to assume that the turn to forms of religion is merely about the desperate need for goods that the Austerity State has not been willing to provide. There is more at stake here, far more indeed than Pentecostalism, which has earned our attention, but which is not alone in its work in the slums of the urban poor. Trends similar to Pentecostalism are visible in societies that are dominated by other religious traditions. For instance, the da’wa (‘preachers’) of the Arab world, such as the Egyptian televangelist Amr Khaled, provide a similar kind of balm, while in India, the Art of Living Foundation and a range of small-time sadhus (‘holy men’) along with the Tablighi Jamaat (‘Society for Spreading Faith’) movement provide their own solace.

What unites these social forces is that they do not focus on eschatology, the concern with death and judgment that governs older religious traditions. These new religious forms are focused on life and on living (‘I am the resurrection and the life’, from John 11:25, is a favourite of Pentecostals). To live is to live in this world, to seek fortune and fame, to adopt all the ambitions of a neoliberal society into religion, to pray not to save one’s soul but for a high rate of return. This attitude is called the Life Gospel or the Prosperity Gospel, whose essence is captured in Amr Khaled’s questions: ‘How can we change the whole twenty-four hours into profit and energy? How can we invest the twenty-four hours in the best way?’. The answer is through productive work and prayer, a combination that the geographer Mona Atia calls ‘pious neoliberalism’.

Reference photograph: Doing the Ring Shout in Georgia, ca. 1930s, photographer unknown. Sourced from the Lorenzo Dow Turner Papers, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Amidst the despair of great poverty in the Austerity State, these new religious traditions provide a form of hope, a prosperity gospel that suggests that God wants those who struggle to gain wealth in this world and that measures salvation not in terms of divine grace in the afterlife but in the present balance of one’s bank account. Through the affective seizure of hope, these religious institutions, by and large, promote social ideals that are deeply conservative and hateful towards progress (particularly towards LGBTQ+ and women’s rights and sexual freedom).

Our dossier, an opening salvo into understanding the emergence of this range of religious institutions in the world of the urban poor, holds fast to this seizure of the hope of billions of people:

In order to build progressive dreams and visions of the future, we must foster hope among the people that can be lived in their daily reality. We must also recover and translate our history and the struggle for social rights into popular organisation by creating spaces for education, culture, and community in which people can gain better understandings of reality and engage in daily experiences of collective solidarity, leisure, and celebration. In these endeavours, it is important not to neglect or dismiss new or different ways of interpreting the world, such as through religion, but, rather, to foster open-minded and respectful dialogue between them to build unity around shared progressive values.

This is an invitation to a conversation and to praxis around working-class hope that is rooted in the struggles to transcend the Austerity State rather than surrender to it, as ‘pious neoliberalism’ does.

Reference photograph: The March of Daisies (Marcha das Margaridas), a public action in Brasilia in 2019 involving more than 100,000 women, by Natália Blanco (KOINONIA Ecunumical Presence and Service). Sourced from the ACT Brazil Ecumenical Forum (FEACT).

In February 2013, Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, went to the town of Maarat al-Nu’man and beheaded a seventy-year-old statue of the 11th century poet Abu al-Alaa al-Ma’arri. The old poet angered them because he is often thought of as an atheist, although, in truth, he was mainly anti-clerical. In his book Luzum ma la yalzam, al-Ma’arri wrote of the ‘crumbling ruins of the creeds’ in which a scout rode and sang, ‘The pasture here is full of noxious weeds’. ‘Among us falsehood is proclaimed aloud’, he wrote, ‘but truth is whispered… Right and Reason are denied a shroud’. No wonder that the young terrorists – inspired by their own gospel of certainty – decapitated the statue made by the Syrian sculptor Fathi Mohammed. They could not bear the thought of humanity resplendent.

The post The Perils of Pious Neoliberalism in the Austerity State first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

I have been a reporter for thirty years. During this period, I have been to many former war zones and to active war zones, including in Iraq, Libya, and Syria. I have seen things that I wish I had not seen and that I wish had not been seen by anyone, let alone experienced by anyone. The thing about war zones that is often not talked about is the noise: the loud noises of the military equipment and the sound of gunfire and bombs. The sound of a modern bomb is extraordinary, punctuated as it often is in civilian areas by the cries of little children. More

The post Can the Left Disagree Without Being Disagreeable? appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Balqis Al Rashed (Saudi Arabia), Cities of Salt, 2017.

On 9 December, China’s President Xi Jinping met with the leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to discuss deepening ties between the Gulf countries and China. At the top of the agenda was increased trade between China and the GCC, with the former pledging to ‘import crude oil in a consistent manner and in large quantities from the GCC’ as well to increase imports of natural gas. In 1993, China became a net importer of oil, surpassing the United States as the largest importer of crude oil by 2017. Half of that oil comes from the Arabian Peninsula, and more than a quarter of Saudi Arabia’s oil exports go to China. Despite being a major importer of oil, China has reduced its carbon emissions.

A few days before he arrived in Riyadh, Xi published an article in al-Riyadh that announced greater strategic and commercial partnerships with the region, including ‘cooperation in high-tech sectors including 5G communications, new energy, space, and digital economy’. Saudi Arabia and China signed commercial deals worth $30 billion, including in areas that would strengthen the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Xi’s visit to Riyadh is only his second overseas trip since the COVID-19 pandemic; his first was to Central Asia for the summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in September, where the nine member states (which represent 40% of the world’s population) agreed to increase trade with each other using their local currencies.

Manal Al Dowayan, (Saudi Arabia) I Am a Petroleum Engineer, 2005–07.

At this first China-GCC summit, Xi urged the Gulf monarchs to ‘make full use of the Shanghai Petrol and Gas Exchange as a platform to conduct oil and gas sales using Chinese currency’. Earlier this year, Saudi Arabia suggested that it might accept Chinese yuan rather than US dollars for the oil it sells to China. While no formal announcement was made at the GCC summit nor in the joint statement issued by China and Saudi Arabia, indications abound that these two countries will move closer toward using the Chinese yuan to denominate their trade. However, they will do so slowly, as they both remain exposed to the US economy (China, for instance, holds just under $1 trillion in US Treasury bonds).

Talk of conducting China-Saudi trade in yuan has raised eyebrows in the United States, which for fifty years has relied on the Saudis to stabilise the dollar. In 1971, the US government withdrew the dollar from the gold standard and began to rely on central banks around the world to hold monetary reserves in US Treasury securities and other US financial assets. When oil prices skyrocketed in 1973, the US government decided to create a system of dollar seigniorage through Saudi oil profits. In 1974, US Treasury Secretary William Simon – fresh off the trading desk at the investment bank Salomon Brothers – arrived in Riyadh with instructions from US President Richard Nixon to have a serious conversation with the Saudi oil minister, Ahmed Zaki Yamani.

Simon proposed that the US purchase large amounts of Saudi oil in dollars and that the Saudis use these dollars to buy US Treasury bonds and weaponry and invest in US banks as a way to recycle vast Saudi oil profits. And so the petrodollar was born, which anchored the new dollar-denominated world trade and investment system. If the Saudis even hinted towards withdrawing this arrangement, which would take at least a decade to implement, it would seriously challenge the monetary privilege afforded to the US. As Gal Luft, co-director of the Institute for Analysis of Global Security, told The Wall Street Journal, ‘The oil market, and by extension the entire global commodities market, is the insurance policy of the status of the dollar as reserve currency. If that block is taken out of the wall, the wall will begin to collapse’.

Ghada Al Rabea (Saudi Arabia), Al-Sahbajiea (‘Friendship’), 2016.

The petrodollar system received two serious sequential blows.

First, the 2007–08 financial crisis suggested that the Western banking system is not as stable as imagined. Many countries, including large developing nations, hurried to find other procedures for trade and investment. The establishment of BRICS by Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa is an illustration of this urgency to ‘discuss the parameters for a new financial system’. A series of experiments have been conducted by BRICS countries, such as the creation of a BRICS payment system.

Second, as part of its hybrid war, the US has used its dollar power to sanction over 30 countries. Many of these countries, from Iran to Venezuela, have sought alternatives to the US-dominated financial system to conduct normal commerce. When the US began to sanction Russia in 2014 and deepen its trade war against China in 2018, the two powers accelerated upon processes of dollar-free trade that other sanctioned states had already begun forming out of necessity. At that time, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin called for the de-dollarisation of the oil trade. Moscow began to hurriedly reduce its dollar holdings and maintain its assets in gold and other currencies. In 2015, 90% of bilateral trade between China and Russia was conducted in dollars, but by 2020 it fell below 50%. When Western countries froze Russian central bank reserves held in their banks, this was tantamount to ‘crossing the Rubicon’, as economist Adam Tooze wrote. ‘It brings conflict in the heart of the international monetary system. If the central bank reserves of a G20 member entrusted to the accounts of another G20 central bank are not sacrosanct, nothing in the financial world is. We are at financial war’.

Abdulhalim Radwi (Saudi Arabia), Creation, 1989.

BRICS and sanctioned countries have begun to build new institutions that could circumvent their reliance on the dollar. Thus far, banks and governments have relied upon the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) network, which is run through the US Federal Reserve’s Clearing House Interbank Payment Services and its Fedwire Funds Service. Countries under unilateral US sanctions – such as Iran and Russia – were cut off from the SWIFT system, which connects 11,000 financial institutions across the globe. After the 2014 US sanctions, Russia created the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), which is mainly designed for domestic users but has attracted central banks from Central Asia, China, India, and Iran. In 2015, China created the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), run by the People’s Bank of China, which is gradually being used by other central banks.

Alongside these developments by Russia and China are a range of other options, such as payment networks rooted in new advances in financial technology (fintech) and central bank digital currencies. Although Visa and Mastercard are the largest companies in the industry, they face new rivals in China’s UnionPay and Russia’s Mir, as well as China’s private retail mechanisms such as Alipay and WeChat Pay. About half of the countries in the world are experimenting with forms of central bank digital currencies, with the digital yuan (e-CNY) as one of the more prominent monetary platforms that has already begun to side-line the dollar in the Digital Silk Roads established alongside the BRI.

As part of their concern over ‘currency power’, many countries in the Global South are eager to develop non-dollar trade and investment systems. Brazil’s new minister of finance from 1 January 2023, Fernando Haddad, has championed the creation of a South American digital currency called the sur (meaning ‘south’ in Spanish) in order to create stability in interregional trade and to establish ‘monetary sovereignty’. The sur would build upon a mechanism already used by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay called the Local Currency Payment System or SML.

Sarah Mohanna Al Abdali (Saudi Arabia), Kul Yoghani Ala Laylah (‘Each to Their Own’), 2017.

A March 2022 report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) entitled ‘The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance’ showed that ‘the share of reserves held in US dollars by central banks dropped by 12 percentage points since the turn of the century, from 71 percent in 1999 to 59 percent in 2021’. The data shows that central bank reserve managers are diversifying their portfolios with Chinese renminbi (which accounts for a quarter of the shift) and to non-traditional reserve currencies (such as Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and Singaporean dollars, Danish and Norwegian kroner, Swedish krona, Swiss francs, and the Korean won). ‘If dollar dominance comes to an end’, concludes the IMF, ‘then the greenback could be felled not by the dollar’s main rivals but by a broad group of alternative currencies’.

Global currency exchange exhibits aspects of a network-effect monopoly. Historically, a universal medium emerged to increase efficiency and reduce risk, rather than a system in which each country trades with others using different currencies. For years, gold was the standard.

Any singular universal mechanism is hard to displace without force of some kind. For now, the US dollar remains the major global currency, accounting for just under 60% of official foreign exchange reserves. Under the prevailing conditions of the capitalist system, China would have to allow for the full convertibility of the yuan, end capital controls, and liberalise its financial markets in order for its currency to replace the dollar as the global currency. These are unlikely options, which means that there will be no imminent dethroning of dollar hegemony, and talk of a ‘petroyuan’ is premature.

Ramses Younane (Egypt), Untitled, 1939.

In 2004, the Chinese government and the GCC initiated talks over a Free Trade Agreement. The agreement, which stalled in 2009 due to tensions between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, is now back on the table as the Gulf finds itself drawn into the BRI. In 1973, the Saudis told the US that they wanted ‘to find ways to usefully invest the proceeds [of oil sales] in their own industrial diversification, and other investments that contributed something to their national future’. No real diversification was possible under the conditions of the petrodollar regime. Now, with the end of carbon as a possibility, the Gulf Arabs are eager for diversification, as exemplified by Saudi Vision 2030, which has been integrated into the BRI. China has three advantages which aid this diversification that the US does not: a complete industrial system, a new type of productive force (immense-scale infrastructure project management and development), and a vast growing consumer market.

Western media has been near silent on the region’s humiliating loss of economic prestige and dominance during Xi’s trip to Riyadh. China can now simultaneously navigate complex relations with Iran, the GCC, Russia, and Arab League states. Furthermore, the West cannot ignore the SCO’s expansion into West Asia and North Africa. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and Qatar are either affiliated or in discussions with the SCO, whose role is evolving.

Five months ago, US President Joe Biden visited Riyadh with far less pomp and ceremony – and certainly with less on the table to strengthen weakened relations between the US and Saudi Arabia. When asked about Xi’s trip to Riyadh, the US State Department’s spokesperson said, ‘We are not telling countries around the world to choose between the United States and the PRC’. That statement itself is perhaps a sign of weakness.

The post The Road to De-Dollarisation Will Run through Saudi Arabia first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

John (Prince) Siddon (Australia), Slim Dusty, Looking Forward, Looking Back, 2021.

On 15 November 2022, during the G20 summit in Bali (Indonesia), Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese told journalists that his country ‘seeks a stable relationship with China’. This is because, as Albanese pointed out, China is ‘Australia’s largest trading partner. They are worth more than Japan, the United States, and the Republic of Korea… combined’. Since 2009, China has also been Australia’s largest destination for exports as well as the largest single source of Australia’s imports.

For the past six years, China has largely ignored Australia’s requests for meetings due to the latter’s close military alignment with the US. Now, in Bali, China’s President Xi Jinping made it clear that the Chinese-Australian relationship is one to be ‘cherished’. When Albanese was asked if Xi raised the issue of Australia’s participation in several military pacts against China, he said that issues of strategic rivalry ‘[were] not raised, except for in general comments’.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd recently said that the impetus for the deep freeze between Australia and China six year ago was the ‘US doctrine of strategic competition’. This outlook is clarified in the 2022 US National Security Strategy, which asserts that China ‘is America’s most consequential geopolitical challenge’. In Bali, US President Joe Biden said that the US and China must ‘manage the competition responsibly’, which suggested that the US might take a less belligerent posture towards China by not pressuring them through US military pacts in Asia and by reducing the intensification of the crisis over Taiwan. Rudd suggests that Biden’s shift in tone might have given Albanese the opportunity to ‘reset’ relations between Australia and China.

Nura Rupert (Australia), Mamu (Spooky Spirits), 2002.

Before Albanese left for Bali, however, news broke about a plan to station six US B-52 bombers, which have nuclear weapons capability, in northern Australia at the Tindal air force base. Additionally, Australia will build 11 large storage tanks for jet fuel, providing the US with refuelling capacity closer to China than its main fuel repository in the Pacific, Hawaii. Construction on this ‘squadron operations facility’ would start immediately and be completed by 2026. The $646 million upgrade includes new equipment and improvements to the US-Australian spy base at Pine Gap, where the neighbouring population in Alice Springs worries about being a nuclear target in a war that they simply do not want.

These announcements come as no surprise. US bombers, including B-52s, have visited the base since the 1980s and taken part in US-Australian training operations since 2005. In 2016, the US commander of its Pacific air forces, General Lori Robinson, said that the US would likely add the B-1 bomber – which has a longer range and a larger payload capacity – to these exercises. The US-Australian Enhanced Air Cooperation (2011) has already permitted these expansions, although this has routinely embarrassed Australian government officials who would prefer more discretion, in part due to the anti-nuclear sentiment in New Zealand and in many neighbouring Pacific island states who are signatories of the 1986 Treaty of Rarotonga that establishes the region as a nuclear-free zone.

Minnie Pwerle (Australia), Bush Melon Seed, 1999.

The expansion of the Tindal air base and the upgrades to Pine Gap spy base are part of the overall deepening of military and strategic ties between the US and Australia. These ties have a long history, but they were formalised by the Australia-New Zealand-United States (ANZUS) Security Treaty of 1951 and Australia’s entry into the Five Eyes intelligence network in 1956. Since then, the two countries have tightened their security linkages, such as by facilitating the transfer of military equipment from the US arms industry to Australia. In 2011, US President Barack Obama and Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard agreed to position a few thousand US Marines in Darwin and Northern Australia and allow US bombers frequent flights to that base. This was part of Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’, which signalled the US pressure campaign against China’s economic advancement.

Two new security alignments – the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad, restarted in 2017) and AUKUS (2021) – further enhanced these ties. The Quad brought together India and Japan with Australia and the US. Since 1990, Australia has hosted Exercise Pitch Black at Tindal, a military war game on which it has collaborated with various countries. Since India’s air force joined in 2018 and Japan participated in 2022, all Quad and AUKUS members are now a part of this large airborne training mission. Australian officials say that after Tindal’s expansion, Exercise Pitch Black will increase in size. In October 2022, Prime Minister Albanese and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida updated their 2007 bilateral security pact. The new ‘reciprocal access agreement’ was signed in response to ‘an increasingly severe strategic environment’, according to Kishida, and it allows the two countries to conduct joint military exercises.

China’s foreign ministry responded to news of the expansion of Tindal and Pine Gap by saying, ‘Such a move by the US and Australia escalates regional tensions, gravely undermines regional peace and security, and may trigger an arms race in the region’.

Qiu Zhi Jie (China), Map of Mythology, 2019.

Albanese walked into the meeting with Xi hoping to end China’s trade restrictions on Australia. He left with optimism that the $20 billion restrictions imposed in 2020 would be lifted soon. ‘It will take a while to see improvement in concrete terms going forward’, he said. However, there is no word from China about removing these restrictions, which limit the import of Australian barley, beef, coal, cotton, lobsters, timber, and wine.

These restrictions were triggered by then Prime Minister of Australia Scott Morrison’s insinuation that China was responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before that, in 2018, Australia’s government banned two Chinese telecommunications firms (Huawei and ZTE) from operating in its jurisdiction. This was not a trivial policy change, since it meant a drop from $19 billion in Australia’s trade with China in July 2021 to $13 billion in March 2022.

Fu Wenjun (China), Red Cherry, 2018.

During the meeting in Bali between Albanese and Xi, the Australian side presented a list of grievances, including Beijing’s restrictions on trade and Australia’s concerns about human rights and democracy in China. Australia seeks to normalise relations in terms of trade while maintaining its expanded military ties with the United States.

Xi did not put anything on the table. He merely listened, shook hands, and left with the assurance that the two sides would continue to talk. This is a great advance from the ugly rhetoric under Scott Morrison’s administration.

In October 2022, China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, gave an address in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Australia and China, which will be celebrated on 21 December. During this talk, Ambassador Qian asked his Australian counterparts if they saw China as ‘a champion or a challenger’ of the international order. Australia’s government and press, he suggested, sees China as a ‘challenger’ of the UN Charter and the multilateral system. However, he said, China sees itself as a ‘champion’ of greater collaboration between countries to address common problems.

The list of concerns that Albanese placed before Xi signals that Australia, like the US, continues to treat China as a threat rather than a partner. This general outlook towards China makes any possibility of genuine normalisation difficult. That is why Ambassador Qian called for Australia to have ‘an objective and rational perception’ of China and for Canberra to develop ‘a positive and pragmatic policy towards China’.

Zeng Shanqing (China), Vigorous Horse, 2002.

Growing anti-Chinese sentiment within Australia poses a serious problem for any move towards normalisation. In July 2022, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that Australia would have to ‘correct’ several of its views on China before relations could advance. A recent poll shows that three-quarters of Australia’s population believes that China might be a military threat within the next two decades. The same survey showed that nearly 90% of those polled said that the US-Australia military alliance is either very or fairly important. At the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore earlier this year, Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles said that countries must engage each other through dialogue and diplomacy. ‘China is not going anywhere. And we all need to live together and, hopefully, prosper together’, he noted.

That Albanese and Xi met in Bali is a sign of the importance of diplomacy and dialogue. Albanese will not be able to get the trade benefits that Australia would like unless there is a reversal of these attitudes and the US-Australia military posture towards China.

The post Nothing Good Will Come from the New Cold War with Australia as a Frontline State first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

The M23 rebels—backed by Rwanda—have expanded their attacks in the DRC. In retaliation, the DRC expelled Rwandan Ambassador Vincent Karega. The M23 with the assistance of Rwanda troops captured Kiwanja and Rutshuru, two towns in the DRC’s North Kivu province. Rwanda argues that it was the DRC that violated agreements leading to the fighters being reinstated. More

The post The Waters are Running Red in Africa’s Great Lakes Region appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

K.C.S. Paniker (India), Words and Symbols, 1968

K.C.S. Paniker (India), Words and Symbols, 1968

In 1845, Karl Marx jotted down some notes for The German Ideology, a book that he wrote with his close friend Friedrich Engels. Engels found these notes in 1888, five years after Marx’s death, and published them under the title Theses on Feuerbach. The eleventh thesis is the most famous: ‘philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it’.

For the past five years, we, at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, have considered this thesis with great care. The most widely accepted interpretation of this thesis is that, in it, Marx urges people not only to interpret the world, but also to try and change it. However, we do not believe that this captures the meaning of the sentence. What we believe that Marx is saying is that it is those who try to change the world that have a better sense of its constraints and possibilities, for they come upon what Frantz Fanon calls the ‘granite block’ of power, property, and privilege that prevents an easy transition from injustice to justice. That is why we, at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, develop our analysis from the wisdom that political and social movements have accumulated over the years. We believe that those who struggle to change the world have a certain clarity about the structures that define it.

Francis Newton Souza (India), The Foreman, 1961

Francis Newton Souza (India), The Foreman, 1961

People’s movements across the world emerge out of the greviences and hopes of workers and peasants, of people who are exploited to accumulate capital for the propertied few and oppressed by social hierarchies. If enough people refuse to submit to the obstinate facts of hunger or illiteracy, their actions could turn into a rebellion, or even into a revolution. This refusal to submit requires confidence and clarity.

Confidence is mysterious, at times a force of personality, at others a force of experience. Clarity comes from knowing who exercises the levers of exploitation and oppression and how these systems of exploitation and oppression work. This knowledge emerges out of the experiences of work and life, but it is sharpened through the struggle to transcend these conditions.

Confidence and clarity that are built in the struggle can dissipate easily unless they are accumulated in an organisation, such as a peasants’ union, a women’s organisation, a trade union, a community group, or a political party. As these organisations grow and mature, they inculcate the habit of carrying out research led by the people and, in doing so, build a historical consciousness, an analysis of the political conjuncture, and a clear assessment of the vectors of hierarchy.

This process of conducting activist research is the heart of the interview we conducted with R. Chandra of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) for our dossier no. 58 (November 2022). Chandra tells us the story of how AIDWA activists conducted surveys in the southern state of Tamil Nadu to best understand the living and working conditions of women there, and she explains how these surveys have provided information about exploitation and oppression that has become the basis of AIDWA’s campaigns. Through these campaigns, AIDWA has learned more about the ‘granite block’ of power, privilege, and property. The recursive process between struggle and survey has enabled the organisation to build their theory and strengthen their struggle.

Chandra goes into detail to show us how AIDWA designed the surveys, how local activists conducted them, how their results led to concrete struggles, and how they trained AIDWA members to develop a clear assessment of their society and the struggles that are needed to overcome the challenges people face. ‘AIDWA members no longer need a professor to help them’, Chandra tells us. ‘They formulate their own questions and conduct their own field studies when they take up an issue. Since they know the value of the studies, these women have become a key part of AIDWA’s local work, bringing this research into the organisation’s campaigns, discussing the findings in our various committees, and presenting it at our different conferences’.

This activist research not only produces knowledge of the hierarchies that operate in a particular place, but it also trains the activists to become ‘new intellectuals’ of their struggles and leaders in their communities.

Over the years, based on interviews with movement leaders from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, our team at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research has begun to develop our own methodology of activist research, a methodology to build knowledge out of praxis. This methodology consists of five main axes:

- Our researchers meet with leaders of popular movements and conduct long interviews with them about the following:

- The history of the movement

- The process to build the movement

- The limitations and strengths of the movement

- Our team then studies the interview, reads the transcript carefully, and provides an analysis of what the movement has summarised and what kind of theory it has been developing. The initial interview could be published as a text by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, as we have done with interviews with K. Hemalata, president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, S’bu Zikode of Abahlali baseMjondolo, South Africa’s shack dwellers’ movement, and Neuri Rossetto of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement.

- Based on the analysis presented in the interview, the researchers isolate the main themes that appear to be useful and make a note to study them further. These themes are then shared with the movement’s leaders for their input.

- When there is agreement on these themes, our researchers – sometimes alongside researchers from the movement, sometimes on their own – work to build a process to study these themes by reading relevant academic literature and conducting more research in coordination with the movement (such as more interviews) as well as carrying out surveys amongst the people. This research forms the heart of the project.

- The research is then analysed, elaborated into a text, and shared with the movement’s leaders for their input and assessment. A final text for publication is produced in collaboration with the movement.

This is how we carry out our work, our form of activist research that we learned from organisations such as AIDWA.

As we published our dossier on activist research, heads of state and representatives from across the world gathered in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt) at the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP) for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, a conference detached from the mood of the people. This is the 27th COP, funded, among others, by Coca-Cola, a major abuser of water and the planet. Meanwhile, in Cairo, not far from this resort town, the human rights activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah sits in prison, where he has been for the past decade. He has decided to deepen his hunger strike by no longer drinking water, water that is increasingly privatised by companies such as Coca-Cola and stolen, as Guy Standing puts it, from the Blue Commons. Nothing good will come out of this COP, no agreement to prevent the climate catastrophe.

Last year, I attended the COP26 meeting in Glasgow. While standing in the queue for a PCR test, I met a group of oil executives, one of whom looked at my press badge and asked me what I was doing at the conference. I told him that I had recently reported about the horrendous situation in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique, where the people were in open rebellion against a gas extraction project led by the French and US companies Total and ExxonMobil, respectively. Despite the profits generated from the gas taken from their region, the people have continued to live in abject poverty. Rather than addressing this inequity, the governments of Mozambique, France, and the United States alleged that the protestors were terrorists and asked the military from Rwanda to intervene.

As we stood in line, one of the oil executives told me, ‘Everything you say is true. But no one cares’. An hour later, sitting in a hall in Glasgow, I was asked my opinion about the climate debate, whose terms have been shaped by fossil fuel executives and privatisers of nature. This is what I said:

The post Those Who Struggle to Change the World Know It Well first appeared on Dissident Voice.Sadly, a year later, this intervention remains intact.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

Heloisa Hariadne (Brazil), Com uma gota já se faz oceano pra sede se matar em mergulho (‘A drop of water becomes an ocean to quench a diver’s thirst’), 2021.

In the last week of October, João Pedro Stedile, a leader of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) in Brazil and the global peasants’ organisation La Via Campesina, went to the Vatican to attend the International Meeting of Prayer for Peace, organised by the Community of Sant’Egídio. On 30 October, Brazil held a presidential election, which was won by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, affectionately known as Lula. A key part of his campaign addressed the reckless endangerment and destruction of the Amazon by his opponent, the incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro. Lula’s victory, helped along by vigorous campaigning by the MST, provides hope for our chance to save the planet. This week’s newsletter contains the speech that Stedile gave at the Vatican. We hope you find it as useful as we do.

Ricardo Stuckert, Lula visits the MST in Espírito Santo, 2020.

Today, humanity is at risk because of senseless social inequality, attacks on the environment, and an unsustainable consumption pattern in rich countries that is imposed on us by capitalism and its profit-seeking mentality.

Part 1: What are the dilemmas facing humanity?

- Climate change is permanent, and its impacts manifest every day with intense heat waves, global warming, torrential rains, tropical cyclones, and droughts in different regions across the planet.

- The number of disasters/crimes has increased five-fold in the last 50 years, killing 115 people and causing economic losses of $202 million per day.

- Environmental crimes have increased, such as deforestation, the burning of tropical forests, and attacks on all biomes, especially in the Global South. In 2021 alone, the world lost1 million hectares of tropical forests.

- The Amazon rainforest, which stretches across nine countries, has already lost 30% of its vegetation cover as a result of encroaching deforestation caused by the push to produce timber and make way for cattle ranching and soybean production, which are exported to Europe and China.

- All biomes in the Global South are being destroyed to produce raw agricultural materials for the Global North.

- Predatory mining affects the environment, water, and land as well as Indigenous and peasant communities as thousands of garimpeiros (illegal miners) mine gold and diamonds using hazardous materials such as mercury in Indigenous lands.

- Never have so many agrotoxins (agricultural poisons) been used in agriculture in the South, affecting soil fertility, killing biodiversity, polluting groundwater and rivers, and contaminating what is produced and even the atmosphere.

- Glyphosate is scientifically proven to cause cancer. Some 42,700 US farmers who contracted cancer won the right to compensation from the companies that produce, sell, and use the glyphosate to which they were exposed.

- Across the planet, more and more genetically modified seeds are being planted, including, as of 2019, a total of nearly 200 million hectares concentrated in 29 countries. These seeds cause genetic contamination in non-GMO seeds, affecting human health and destroying the planet’s biodiversity because they require the use of agrotoxins.

- The oceans are polluted by plastics and other human waste, killing many species of fish and marine life. The massive use of chemical fertilisers has also caused ocean waters to acidify, putting all marine life at risk. Evidence of this can be seen in the large garbage patch in the Pacific Ocean, which covers over a million square kilometres.

- The carbon dioxide emitted by burning fossils fuels and by individual transportation in automobiles causes pollution in large cities, which in turn causes the death of thousands of people, with 7,100 in the northeast and Mid-Atlantic region of the United States alone dying as a result of vehicle emissions in a single year.

- Humanity is suffering under a public health crisis that is also inextricably connected to nature. Epidemics and pandemics have increased, creating a massive global health crisis that puts millions of people at risk. This phenomenon, often propelled by the increased transmission of diseases from animals to human beings (known as zoonoses), is a result of the simultaneous destruction of biodiversity alongside the expansion of the agricultural frontier by agribusiness and energy, mining, and transportation megaprojects as well as urban and large-scale livestock farming.

- Many areas on our planet are protected by peasant and Indigenous communities. Capital attacks and seeks to destroy them in order to take control of the natural goods they protect.

- We are undergoing an ecological-social crisis of the Earth system and of the balance of life. This global crisis affects the environment, the economy, politics, society, ethics, religions, and the meaning of our own life.

- The billions of the world’s poorest people are the most impacted by the lack of food, water, housing, employment, income, and education. Deteriorating living conditions have forced them to migrate and have killed thousands of people, especially children and women.

- This generalised crisis is endangering human life. Without bold action, the planet, which is under attack, could still regenerate, but without human beings.

Eduardo Berliner (Brazil), House, 2019.

Part 2: Who is responsible for putting humanity at risk?

- Capitalism is facing a structural crisis. It is no longer capable of organising the production and distribution of goods that people need. Its logic of profit and capital accumulation prevent us from having a more just and egalitarian society.

- This crisis manifests itself in the economy, in increasing social inequality, in the state’s failure as a guarantor of social rights, in formal democracy’s failure to respect the will of most people, and in the propagation of false values based solely on individualism, consumerism, and selfishness. This system is economically and environmentally unsustainable, and we must put it behind us.

- The main parties directly responsible for the environmental crisis are large transnational corporations, which do not respect borders, states, governments, or the rights of peoples. Some of these corporations, such as Bayer, BASF, Monsanto, Syngenta, and DuPont, manufacture agrotoxins, while others run the mining, automobile, and fossil fuel-run electric energy sectors, and yet others control the water market (such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Nestlé) and the world food market. Associated with all of them are banks and their financial capital. In the last decade, these corporations have been joined by powerful transnational technology corporations, which control ideology and public opinion (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Facebook/Meta, and Apple). The owners of these companies are among the richest people in the world.

- However, corporations are not the only ones to blame for the environmental crisis; they are aided by:

- governments that cover up and protect corporate crime;

- the mainstream media, which seek profit and serve corporate interests all whilst deceiving the people and hiding those who are responsible; and

- international organisations formed by governments and captured by large corporations under the cover of phantom foundations, which directly influence these organisations and only repeat rhetoric and hold ineffective international meetings such as the Conference of the Parties (COP), which has now met 27 times. This is even the case with the United Nations and the Food and Agricultural Organisation.

All of these entities must respect the law.

- I welcome the courageous position taken by Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2022 and the encyclicals of Pope Francis. Both are a wake-up call to the entire world.

Tarsila do Amaral (Brazil), O Vendedor de frutas (‘The Fruit Vendor’), 1925.

Part 3: What solutions are we calling for?

There is still time to save humanity, and, with it, our common home, planet Earth. For this we need to have the courage to implement concrete and urgent measures on a global level. On behalf peasants’ movements and people’s movements in urban peripheries, we propose:

- Prohibiting deforestation and commercial burning in all native forests and savannas across the world.

- Prohibiting the use of agrotoxins and genetically modified seeds in agriculture, as well as antibiotics and growth promoters in livestock farming.

- Condemning all decoy solutions to climate change and geoengineering techniques proposed by capital that speculate on nature, including the carbon market.

- Prohibiting mining in the territories of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities as well as environmental protection and conservation areas and demanding that all mining be publicly controlled and used for the common good – not for profit.

- Strictly controlling the use of plastics, including in the food and beverage industry, and making it mandatory to recycling them.

- Recognising nature’s goods (such as forests, water, and biodiversity) as universal common goods at the service of all people that are immune to capitalist privatisation.

- Recognising peasants as the main caretakers of nature. We must fight against large landowners and carry out popular agrarian reforms so that we can combat social inequality and poverty in the countryside and produce more food in harmony with nature.

- Implementing an extensive reforestation program, paid for with public resources, that ensures the ecological recovery of all areas near springs and riverbanks, slopes, and other ecologically sensitive areas or areas that are experiencing desertification.

- Implementing a global policy to care for water that prevents the pollution of oceans, lakes, and rivers and that eliminates the contamination of surface and subsoil drinking water sources.

- Defending the Amazon and other tropical forests of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands as ecological territories under the care of the peoples of their countries.