Speaking at a carpenters’ training facility in Pittsburgh on Wednesday, President Joe Biden unveiled an economic recovery proposal called the American Jobs Plan, a plan reminiscent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in scope and ambition. It would pump $2 trillion into the economy this decade and heavily invest in fighting climate change and building green infrastructure. “This is no time to build back to the way things were,” the White House said in its preview of the plan. “This is the moment to reimagine and rebuild a new economy.”

That’s exactly what this plan would do over the next eight years. The American Jobs Plan would direct $621 billion toward transportation infrastructure, with $174 billion of that going toward building out the U.S.’s electric vehicle market. It would pour $111 billion into shoring up the nation’s crumbling water infrastructure and eliminate all lead pipes and service lines. It would direct $100 billion toward revamping the country’s electric infrastructure, in no small part to avoid the kind of power crises that have hit different parts of the country, most recently Texas, in the wake of extreme weather. The plan shoots for 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035 — a timeline climate activists pushed Biden toward during his presidential campaign.

More than $200 billion would go to “produce, preserve, and retrofit more than two million affordable and sustainable places to live.” One hundred billion would go toward workforce development, and a portion of that money would be dedicated to job training programs for green industries. Workers who lose their jobs “through no fault of their own” — think out-of-work coal miners — would have access to a Dislocated Workers Program that would train them in new skills for sectors like clean energy, manufacturing, and caregiving.

Bridges would get fixed, roads would be repaved, tunnels would be bolstered. The plan has money for communities displaced by climate change and funding for “nature-based” solutions such as forests, wetlands, and watersheds. And 40 percent of the benefits of the investments in climate and clean infrastructure would go to disadvantaged communities.

“The American Jobs Plan will lead to a transformational progress in our effort to tackle climate change with American jobs and American ingenuity,” Biden said on Thursday, and “protect our community from billions of dollars of damage from historical superstorms, floods, wildfires, droughts, year after year.”

The White House says the plan would be paid for by reversing the Trump administration’s 2017 tax cuts for corporations and levying new taxes on corporations and wealthy Americans. Biden would raise the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent and eliminate billions of dollars in subsidies for fossil fuels, something he promised to do on the campaign trail. Biden promised that the plan wouldn’t raise taxes on Americans making less than $400,000.

The American Jobs Plan is a blueprint for what Biden wants Congress to do. The bill legislators come up with could look different from what the White House announced this week. And in order for whatever plan eventually gets written to actually become law, the Biden administration and both chambers of Congress will have to navigate a series of tricky hurdles. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi says she wants the House to pass this infrastructure and jobs bill by July 4, which means she has just six weeks in session to make it happen. The progressive members of her caucus are already getting ready to rumble — they say the plan isn’t ambitious enough. Pelosi will have to do some wheeling and dealing to get her moderates in line, too. The veteran lawmaker is likely up to the challenge, though the timing is tight.

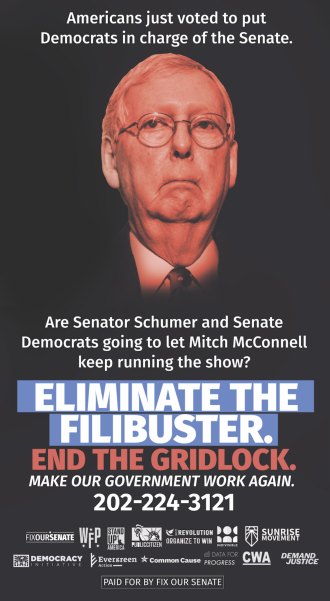

The bill will run into more serious roadblocks in the Senate, where Democrats’ majority is razor-thin. The White House says it wants to work with Republicans to pass the plan, but, even though infrastructure has historically been one of the rare legislative arenas where both parties have been able to find middle ground, many Republicans are almost certainly going to vote against it. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell is already gearing up for a fight over the proposed corporate tax hike. The White House will keep pushing for bipartisanship, but the reality is that this bill will likely get passed via the budget reconciliation process — which allows legislators to pass spending and tax measures while bypassing the filibuster process that allows the minority party to block any Senate bill that doesn’t have 60 votes. But the rules that govern the budget reconciliation process are strict, and squeezing all of Biden’s hopes and dreams into a form that fits the process will be tough.

Democrats have incentives to push Biden’s agenda through. Polling from the progressive think tank Data for Progress and the climate PR campaign Climate Power shows a majority of voters think the federal government should be doing more to bring America’s infrastructure up to speed. The question is whether voters like infrastructure enough to vote blue in 2022 and 2024.

“The divisions of the moment shouldn’t stop us from doing the right thing for the future,” Biden said in Pittsburgh.

Biden has come a long way since the Democratic primary, when the subdued former vice president promised to make America normal again. The next several months will determine whether the Democrat can pull off one of the biggest economic transformations since World War II.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Biden unveils a ‘once-in-a-generation’ infrastructure plan in Pittsburgh on Mar 31, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Hello, I’m Zoya Teirstein, and

Hello, I’m Zoya Teirstein, and