COMMENTARY: By Ian Powell

The 1981 Springbok Tour was one of the most controversial events in Aotearoa New Zealand’s history. For 56 days, between July and September, more than 150,000 people took part in more than 200 demonstrations in 28 centres.

It was the largest protest in the country’s history.

It caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

- READ MORE: 100 children killed or wounded every day since Gaza ceasefire broken

- Other war on Palestine reports

The success of these mass protests was that this was the last tour in either country between the two teams with the strongest rivalry among rugby playing nations.

This deeply rooted antipathy towards the racism of apartheid helps provide context to today’s growing opposition by New Zealanders to the horrific actions of another apartheid state.

Understanding apartheid

Apartheid is a humiliating, repressive and brutal legislated segregation through separation of social groups. In South Africa, this segregation was based on racism (white supremacy over non-whites; predominantly Black Africans but also Asians).

For nearly three centuries before 1948, Africans had been dispossessed and exploited by Dutch and British colonists. In 1948, this oppression was upgraded to an official legal policy of apartheid.

Apartheid does not have to be necessarily by race. It could also be religious based. An earlier example was when Christians separated Jews into ghettos on the false claim of inferiority.

In August 2024, Le Monde Diplomatic published article (paywalled) by German prize-winning journalist and author Charlotte Wiedemann on apartheid in both Israel and South Africa under the heading “When Apartheid met Zionism”:

She asked the pointed question of what did it mean to be Jewish in a country that saw Israel through the lens of its own experience of apartheid?

It is a fascinating question making her article an excellent read. Le Monde Diplomatic is a quality progressive magazine, well worth the subscription to read many articles as interesting as this one.

Relevant Wiedemann observations

Wiedemann’s scope is wider than that of this blog but many of her observations are still pertinent to my analysis of the relationship between the two apartheid states.

Most early Jewish immigrants to South Africa fled pogroms and poverty in tsarist Lithuania. This context encouraged many to believe that every human being deserved equal respect, regardless of skin colour or origin.

Blatant widespread white-supremacist racism had been central to South Africa’s history of earlier Dutch and English colonialism. But this shifted to a further higher level in May 1948 when apartheid formally became central to South Africa’s legal and political system.

Although many Jews were actively opposed to apartheid it was not until 1985, 37 years later, that Jewish community leaders condemned it outright. In the words of Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris to the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

“The Jewish community benefited from apartheid and an apology must be given … We ask forgiveness.”

On the one hand, Jewish lawyers defended Black activists, But, on the other hand, it was a Jewish prosecutor who pursued Nelson Mandela with “extraordinary zeal” in the case that led to his long imprisonment.

Israel became one of apartheid South Africa’s strongest allies, including militarily, even when it had become internationally isolated, including through sporting and economic boycotts. Israel’s support for the increasingly isolated apartheid state was unfailing.

Jewish immigration to South Africa from the late 19th century brought two powerful competing ideas from Eastern Europe. One was Zionism while the other was the Bundists with a strong radical commitment to justice.

But it was Zionism that grew stronger under apartheid. Prior to 1948 it was a nationalist movement advocating for a homeland for Jewish people in the “biblical land of Israel”.

Zionism provided the rationale for the ideas that actively sought and achieved the existence of the Israeli state. This, and consequential forced removal of so many Palestinians from their homeland, made Zionism a “natural fit” in apartheid South Africa.

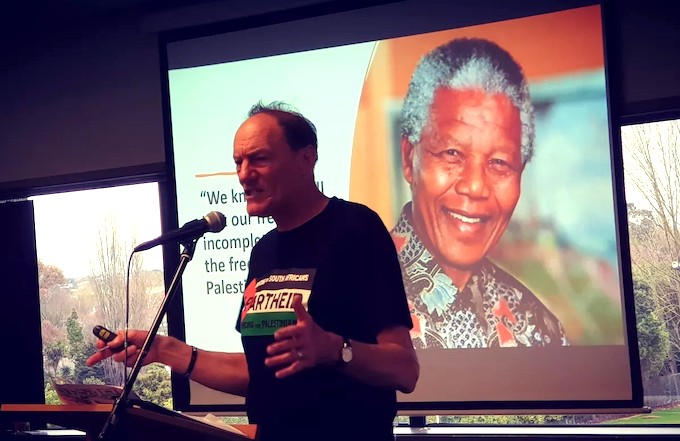

Nelson Mandela and post-apartheid South Africa

Although strongly pro-Palestinian, post-apartheid South Africa has never engaged in Holocaust denial. In fact, Holocaust history is compulsory in its secondary schools.

Its first president, Nelson Mandela, was very clear about the importance of recognising the reality of the Holocaust. As Charlotte Wiedemann observes:

“Quite the reverse . . . In 1994 Mandela symbolically marked the end of apartheid at an exhibition about Anne Frank. ‘By honouring her memory as we do today’ he said at its opening, ‘we are saying with one voice: never and never again!’”

In a 1997 speech, on the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, Mandela also reaffirmed his support for Palestinian rights:

“We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians.”

There is a useful account of Mandela’s relationship with and support for Palestinians published by Middle East Eye.

Mandela’s identification with Palestine was recognised by Palestinians themselves. This included the construction of an impressive statue of him on what remains of their West Bank homeland.

Comparing apartheid in South Africa and Israel

So how did apartheid in South Africa compare with apartheid in Israel. To begin with, while both coincidentally began in May 1948, in South Africa this horrendous system ended over 30 years ago. But in Israel it not only continues, it intensifies.

Broadly speaking, this included Israel adapting the infamously cruel “Bantustan system” of South Africa which was designed to maintain white supremacy and strengthen the government’s apartheid policy. It involved an area set aside for Black Africans, purportedly for notional self-government.

In South Africa, apartheid lasted until the early 1990s culminating in South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994.

Tragically, for Palestinians in their homeland, apartheid not only continues but is intensified by ethnic cleansing delivered by genocide, both incrementally and in surges.

Apartheid Plus: ethnic cleansing and genocide

Israel has gone further than its former southern racist counterpart. Whereas South Africa’s economy depended on the labour exploitation of its much larger African workforce, this was relatively much less so for Israel.

As much as possible Israel’s focus was, and still is, instead on the forcible removal of Palestinians from their homeland.

This began in 1948 with what is known by Palestinians as the Nakba (“the catastrophe”) when many were physically displaced by the creation of the Israeli state. Genocide is the increasing means of delivering ethnic cleansing.

Ethnic cleansing is an attempt to create ethnically homogeneous geographic areas by deporting or forcibly displacing people belonging to particular ethnic groups.

It can also include the removal of all physical vestiges of the victims of this cleansing through the destruction of monuments, cemeteries, and houses of worship.

This destructive removal has been the unfortunate Palestinian experience in much of today’s Israel and its occupied or controlled territories. It is continuing in Gaza and the occupied West Bank.

Genocide involves actions intended to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

In contrast with civil war, genocide usually involves deaths on a much larger scale with civilians invariably and deliberately the targets. Genocide is an international crime, according to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948).

Today the Israeli slaughter and destruction in Gaza is a huge genocidal surge with the objective of being the “final solution” while incremental genocide of Palestinians speeds up in the occupied West Bank.

Notwithstanding the benefits of the recent ceasefire, it freed up Israel to militarily focus on repressing West Bank Palestinians.

Meanwhile, Israel’s genocide in Gaza during the current vulnerable hiatus of the ceasefire has shifted from military action to starvation.

The final word

One of the encouraging features has been the massive protests against the genocide throughout the world. In a relative context, and while not on the same scale as the mass protests against the racist South African rugby tour in 1981, this includes New Zealand.

Many Jews, including in New Zealand and in the international protests such as at American universities, have been among the strongest critics of the ethnic cleansing through genocide of the apartheid Israeli state.

They have much in common with the above-mentioned Bundist focus on social justice in contrast to the dogmatic biblical extremism of Zionism.

Amos Goldberg, professor of genocidal studies at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem is one such Jew. Let’s leave the final word to him:

“It’s so difficult and painful to admit it, but we can no longer avoid this conclusion. Jewish history will henceforth be stained.”

This is a compelling case for the New Zealand government to join the many other countries in formally recognising the state of Palestine.

Ian Powell is a progressive health, labour market and political “no-frills” forensic commentator in New Zealand. A former senior doctors union leader for more than 30 years, he blogs at Second Opinion and Political Bytes, where this article was first published. Republished with the author’s permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.