Stupidity, stupidity everywhere – and not a word to witness.

“Stupid” is a commonplace term casually used in everyday conversation. Much less so in writing – especially when the subject is political personalities. It is heavily weighted with inhibition. Why this hesitation? Why at a time when manifest stupidity in speech and action is rampant?

“Stupid” is both blunt and conclusive. Straight-forward. It does not welcome qualification or discussion. It implies: matter settled, closed. Moreover, it suggests a character flaw as well as low intelligence. That somehow makes us uncomfortable. So we prefer: dense, slow, thick, dim or dim-witted; or pithy euphemisms, e.g. “not the sharpest tool in the kit” or “none too swift” or “slow on the uptake” or “not playing with a full deck” or “in so far over his head that the bubbles don’t reach the surface.” In addition, there are those words that refer directly to intelligence: moron, imbecile, idiot. They, too, are in currency but suffer from the disability of taking in vain a descriptive word that refers to the poor souls who are born with mental deficiencies.

“Stupid” is used as an epithet 95% of the time. Not as a depiction of someone’s Intelligence Quotient (IQ). To do so in the latter sense is to complicate matters. Intelligence, as we now are aware, is a broad concept that covers 5 or 6 or 7 mental attributes whose correlations are quite low. So, almost no one thinks that through before throwing the word around. To the degree that one might consider meanings, it implies lack of logic – the core characteristic of conventional IQ intelligence.

Squirt kerosene on a simmering barbecue – that’s stupid. Sending more troops to Afghanistan in 2017 when you’ve failed miserably to achieve your (undefined) objective over the past 15 years with much larger contingents is stupid, i.e., illogical. Denouncing China as America’s enemy on whom it plans to impose severe economic sanctions while senior officials publicly predict war within 10 years, and then beseeching Beijing for assistance in keeping the dollar the global currency by ending its sale of U.S. securities; and then demanding that China slow its economic growth because 1) it causes balance-of-trade imbalances, and 2) that would reduce its oil imports thereby minimizing Russian revenue from its sales on a softer world market (as did Janet Yellin on two separate visits) – that’s stupid. Silently letting Turkey provide crucial material support to ISIS and al-Qaeda in Syria while decrying terrorist acts by jihadis in the US and Europe is stupid, i.e., illogical. (The Obama administration soon joined in supplying arms indirectly those same groups, then helped secure their control of the Idlib enclave which was their base for the eventual breakout a few months ago; now in power they are massacring Alawites and Christians). Bestowing praise and honors on the Saudi leaders as declared brothers in the “war on terror” when in fact these very persons have done more to propagate the fanatical creed that inspires and justifies acts of terror is stupid, i.e., “illogical.”

These instances of stupid behavior draw our attention to the connections between intelligence and knowledge – between “stupidity” and “ignorance.” Stupid (illogical) behavior is more likely when you don’t know what you’re doing because important information is missing. In the examples cited, though, the information that is the foundation for logical thinking was known to the parties taking those actions. Not just accessible – it is lodged (somewhere) in the brain of the actor. “Dumb” in popular usage is the word that combines “stupid” and “ignorant” – with the connotation that the ignorance is willful. That is a pertinent notion to which we’ll return.

Assuming that the “stupid’ actors are not mentally deficient, why do they act as if they are? That is the persistent question that crops us as we see and read the antics of public officials, commentators, and a host of celebrity personalities. Several explanations, not excuses, come to mind.

One is that there exists an implicit logic that is not acknowledged but salient for the person(s) involved. The Pentagon brass may well have been less concerned about “winning” in Afghanistan, whatever that means, than they were living with the intolerable perception that they “lost.” No general cum security policy-maker wants to be saddled with the label of “loser.” That sensitivity can become institutionally generalized; Generals Mattis and McMaster were in little danger of being blamed personally for failure in Afghanistan. What seems to count is that they did not want the U.S. military to be stigmatized as a failure. They were acutely aware of how much the image of the uniformed military suffered as a result of America losing its first war in Vietnam. It follows that they might hope against hope that the outcome can be fudged enough so as to escape that fate. There is a practical side to this concern, too. Failure, as perceived in the public eye, could tarnish the resplendent image so successfully cultivated during the “war on terror” era. That could translate into less support for bigger budgets, less lucrative consultancies after retirement, and less acclaim. And a weaker voice in policy debates.

If one were to postulate that these are cardinal objectives, then campaigning to send several thousand more troops on a strategically pointless mission is logical – and the plan’s promoters not as stupid as they appear. What of senior policymakers in and around the White House who did not share those particular interests? They, indeed, were stupid.

Another instructive example is Barack Obama’s announcing the conclusion of an historic, arduously negotiated nuclear treaty with Iran (JPOA) in a speech that vilifies the Tehran regime as a tyranny that sponsors terrorism, aims to dominate the Persian Gulf, and endangers Israel. Thereby, he emboldened opponents of the accord to attack it – clearing the way for its abrogation by Trump a few years later. The net result: we now are on the brink of war with Iran because of its nuclear activities. Stupidly illogical? Perhaps not. Obama, on narrow political grounds, was trying to insulate himself from a barrage of criticism from Washington hard-liners and the Zionist lobby. Only two years earlier, he had infuriated them by scotching plans for American military strikes against government forces in response to chemical attacks blamed on the Assad regime (in fact, a false flag operation by MI-6 and their White Hats in collaboration with the jihadi rebels); hence, the perceived need to mollify them. So, it can be seen as logical given his weighting of interests and priorities. Not stupid – just self-centered and unresponsive to the public good, vintage Obama.

A second reality to keep in mind is that governments are plural nouns – or, pronouns with multiple antecedent nouns. The numerous organizations, bureaucracies and individuals involved in decision-making typically lead to a convoluted process wherein it is easy to lose track of purposes, priorities and coordination. Where little discipline is imposed by the chief, the greater the chances that the result will be contradictory, disjointed, sub-optimal and often poorly executed policies. At the present moment, we are witnessing a disjointed Trump administration, that in regard to Ukraine/Russia, 6 individuals are pursuing 7 different lines as indicated by their public remarks – an octopus trying to put on a pair of mismatched socks. All exacerbated by a scatterbrained Chief Executive who contradicts himself – as well his senior deputies – on a nightly basis.

Another kind of impediment to coherent, reality-based policymaking arises when the opposite condition prevails: an elaborate process involving several parties with divergent perspectives and parochial interests concludes with an agreement on a lowest common denominator basis. Arduously reached, that decision becomes frozen, insulated from new information or changes in the environment due to the fear that any revision would unravel the consensus – a form of groupthink. An extreme example of this phenomenon is provided by the EU where 27 sovereign states must agree before any policy can be enunciated. In Brussels, success is proclaimed when they reach accord as if negotiating among themselves is tantamount to negotiating an accord with other governments. A similar example is presented by the current campaign of the Trump administration to press Ukraine into negotiations with Russia. The tussle between Washington and Kiev is taken to be the crucial step toward resolution of the conflict. In fact, the ideas being bandied about as key ingredients of a settlement already have been absolutely rejected by Moscow – in particular, the much ballyhooed ceasefire that is a Western pipedream. As yet, they have not even been formally conveyed to the Russians. Stupid – or pathological?

Finally, we should recognize that rigorous thinking is far from the norm – at the highest levels of government as well as in everyday life. It takes a combination of education/training, experience, intellectual integrity, a cultivated sense of responsibility, discomfort with deciding on the basis of skimpy or suspect information, and an ingrained preference for knowing why you’re doing something instead of flying by the seat of your pants. True, when practiced and reinforced, rigorous thinking can become habitual – just like other modes of human behavior. There are multiple influences, though, that militate against that habit taking root and being sustained. They include the lure of celebrity, time pressures due to an excess of travel and/or summonses to mind-numbing TV interviews, long-tedious-inconclusive meetings (such as those presided over by Susan Rice which drove Chuck Hagel out of government), endless bureaucratic games-playing, distracted Chief Executives who demand ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers to complex issues. Altogether, the tumult can soften the toughest mind. Weaker minds simply latch onto whatever conventional wisdom and catch phrases are floating around in order to remain relevant and minimally functional in the kaleidoscopic setting of most administrations.

All of these patterns with attendant adverse consequences are more likely to crystallize into stupid acts when the man nominally in charge lacks the intelligence, emotional stability, self-awareness and/or advisors to recognize either the requirements for sound policymaking or for implementation. A lack of capacity to accept responsibility and to be held accountable exacerbates matters.

A business career such as Trump’s is not the desired preparation. Not only is that world fundamentally different from the world of public affairs (and especially foreign policy) Further, Trump partially compensated for his flaws through coercion, cheating, and duplicity. And at the end of the day, he could rig the books. That modus operandi doesn’t fly in the Middle East or in dealing with the likes of Vladimir Putin or Xia Jinping. It could, and does, win elections in a country where ignorance and “obtuseness”, in its many inglorious forms, are commonplace.

“Willful ignorance,” or “studied ignorance,” is an increasingly familiar phenomenon. Not just in Washington but among heads of large organizations of all stripes (e.g. universities). The inclination to avoid acquiring knowledge about a matter either at hand or looming is not necessarily a sign of stupidity. Here, too, there may be hidden considerations at play. American foreign policymakers may have wish to mask the Kabul government’s faltering popular support because doing so means a fundamental rethink of aims- an agonizing reappraisal for which they are unprepared intellectually, politically, and diplomatically. (MB: substitute Ukraine)

Making no effort to uncover the facts only becomes “stupid” where the responsible official then does things, as a consequence, that harm his interests. That has been the case in Syria where Barack Obama refused to come to terms with the uncomfortable truth that the “rebels” were overwhelmingly Salafist jihadis. In this case, an admission of that cardinal truth would pose the stark choice between continuing to back an al-Qaeda-led cause or reversing course in tilting toward the Assad regime. The President lacked the courage to deal with the wide-ranging ramifications of that; so, he deluded himself into pursuing a will-o’wisp that existed only in the imaginings of those who were keen on an American military intervention. By surrounding himself with a rogue Secretary of Defense, a strategically disoriented Secretary of State, a self-absorbed, unpracticed National Security Advisor, and an obstreperous UN Ambassador, Obama fostered an environment that enabled his escapist behavior. So, too, did his ritual deference to the warped liturgy of the foreign policy Establishment that they represented.

For a President to avoid acting “stupidly,” he need not have an exceptional IQ – or score remarkably high on other dimensions of intelligence. Two things are most important: he must be honest with himself; and he must put in place a policy system that is both logical in process and self-aware as to why decisions are taken with what end in mind. To borrow an analogy from the football terminology favored in the corridors of Washington power: you can win a championship with a simply competent quarterback if the other pieces are in place and he follows a disciplined script. (Bart Starr of the old Green Bay Packers). An emotionally handicapped or narcissistic quarterback – however talented – will cripple a team sooner or later. One who suffers from the latter condition(s), along with a lack of athletic talent, is a guarantor of disaster. “Stupidity” will be the least of the derogatory terms applied to the ensuing performance; that word should be reserved for those who chose him.

Moral: we should not hesitate to call things as they are. Feigned politeness in situations marked by systematic deceit, ill-will and harm to the nation serves no good purpose. Concerned about the proverbial “dignity of the office?” Take your shoes off before entering the Oval Office. If “stupidity” displayed by stupid people is what we observe, virtue lies in calling it by its name.

The foregoing discussion pertains directly to government leaders. What of those non-official members of the “foreign affairs community” – the think tank pundits, the media personalities, the op ed columnists? These days, the thinking of most mirrors that of those in government positions. The unstated or unconfirmed premises, the partial or selective information, the logical flaws. The main differences are that they write/speak at far greater length, compose longer sentences, and use polysyllabic words. The level of intellectual rigor, though, is pretty much the same.

ENDNOTES:

The post

On Stupidity first appeared on

Dissident Voice.

1 “Dumb” as a pejorative has been out of favor for some time. It sounds stale to the post-modern ear. Only be adding the suffix “SOB” or “bastard” does it make any impact. That may be changing, though. The comeback of “dumb” could well have something to do with the fact that it rhymes with “Trump.” The German spelling “Drump” has even truer resonance.

2 Abu Mohammad al-Julani, nom de guerre of Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa, and Abu Bakra al-Baghdadi of ISIS notoriety were confederates in the al-Qaeda subsidiary al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia that had been active in Iraq after the 2003 American invasion and occupation. Soon after the civil war in Syria broke out in 2011, they went their more or less separate ways: al-Baghdadi leading the Islamic State and Julani controlling al-Nusra as it came to be known. Over time, al-Nusra became the dominant force in the opposition coalition. It used its non-jihadi allies as convenient cover. American aid, along with that of European supporters, was laundered through those other groups. In effect, they served as a postal drop box. Over the eight years when al-Nusra ran the Idlib pocket under Turkish protection, they set up a repressive Islamic autocracy. They also assembled a multiethnic force including ISIS remnants, Uigurs, Uzbeks, Afghans, Chechens that acted as Turkish mercenaries in Libya, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Now, they enjoy a measure of independence as militias in the new-found regime of Jalani’s Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – its latest organizational incarnation. However, they could not commit the massacres against the Alawites without Jolani’s tacit approval, and HTS security forces, too, were involved.

For the record: among Syria’s 4.5 million Alawites, few supported Assad to the end and active opposition to the HTS takeover was very limited.

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Michael Brenner.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

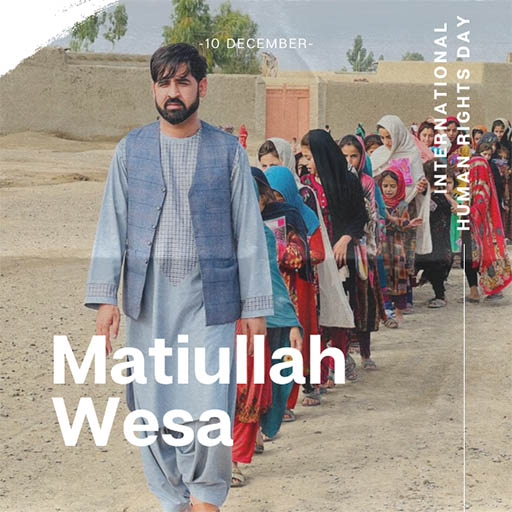

Afghanistan human rights defenders (HRDs), both within the country and in exile, face significant and myriad challenges. Inside Afghanistan, HRDs are not only restricted from continuing their human rights work, but also live under constant threats to their safety due to the Taliban’s intensified violence and atrocities. In particular, women human rights defenders (WHRDs) grapple with an additional level of the Taliban’s unprecedented misogynistic policies, targeting them with systematic discrimination and persecution, amounting to gender apartheid. Many HRDs have been forced into hiding or have managed to flee the country for their survival. Those who sought refuge in transit countries, mainly Iran and Pakistan, face innumerable risks such as deportation, harassment, and economic constraints to their livelihood. Meanwhile, HRDs settled primarily in western countries with comparatively greater security face their own set of difficulties, including concerns about their overall well-being and the lack of a long-term support system to sustain their human rights work while in exile.

Afghanistan human rights defenders (HRDs), both within the country and in exile, face significant and myriad challenges. Inside Afghanistan, HRDs are not only restricted from continuing their human rights work, but also live under constant threats to their safety due to the Taliban’s intensified violence and atrocities. In particular, women human rights defenders (WHRDs) grapple with an additional level of the Taliban’s unprecedented misogynistic policies, targeting them with systematic discrimination and persecution, amounting to gender apartheid. Many HRDs have been forced into hiding or have managed to flee the country for their survival. Those who sought refuge in transit countries, mainly Iran and Pakistan, face innumerable risks such as deportation, harassment, and economic constraints to their livelihood. Meanwhile, HRDs settled primarily in western countries with comparatively greater security face their own set of difficulties, including concerns about their overall well-being and the lack of a long-term support system to sustain their human rights work while in exile.