Orientation

The reason Yankee fans and Red Sox fans hate each other goes a lot deeper than sports. In his book American Nations, Colin Woodard identifies eleven regional cultures in the United States. He compares the conditions of the home country, settler conditions, climate, geography, religious history, population density and international loyalties. He points out the parallels between how settlers’ regional locations in England impacted the type of regional culture they developed in the United States. My purpose in this article is to:

- reveal the political bankruptcy of trying to fit eleven different regions into two political parties; and,

- reveal the economic bankruptcy of industrial capitalists in forming a single nation-state by attempting to pulverize the differences between these regions.

There are good reasons why the United States has rarely, if ever, unified, whether in war or peace. The notion that we were and are united is pure political and economic propaganda.

Questions about regional rivalries

- How might the time of settlement affect the culture of the region and how might the region feel about other regions?

- How might the country of origin and its politics (feudal, capitalist) affect the politics of the region and how might that region feel about different regions?

- How might the geography (rivers, rainfall, flat-mountainous, valleys, plains) and means of subsistence (hunting, fishing, farming, herding, trading, industry) affect the culture of the region and how might that region feel about different regions?

- How might the religion of the region affect the culture and how might that region feel about different regions?

- How might the size of the population of the region (dense or sparse) affect the culture of the region and how might that region feel about different regions?

- How might the history of the region’s relationship with immigrants or native Americans affect the culture of the region and how might that region feel about other regions?

- Given the answer to the first six questions, which regions will have the greatest tensions? Why might they have these tensions?

- The author of the book implies that the United States is too big for a single nation-state. Whether you agree or not, are there any regions that might have enough in common to join together? Or would it be better to be broken into regions that become nation-states like European states?

I cannot address all these questions in this article. I intend to answer most of them and leave the rest to stimulate your thinking.

Issues that Divided the Regions of the United States

The federal government of the United States only began to try to unify the country from the Atlantic to the Pacific after the Civil War with massive architecture, street names, and flags in every classroom. it is questionable how successful they have been. To talk about a common national experience over such a large territory confronts many problems.

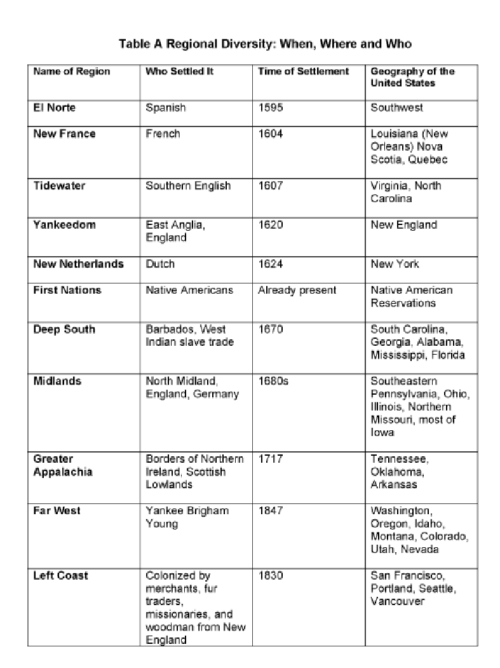

David Hackett Fischer in his book, Albion’s Seed, identified four major regions in the United States with significant differences in their means of subsistence, their religion, the conditions of settlement and the parts of England these first settlers were from. In his book American Nations, Colin Woodard has expanded these settlements from four to eleven regions. Please see Table A to understand which country of Europe settled the region, the time of settlement and the region of the U.S. it occupied.

For this section I will be following Woodard’s description. According to him, Americans have been divided since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth. Colonists saw each other as competitors for people to settle their land, for the land itself, as well their ability to draw capital to their settlement. Here are some of the issues that divided the colonies:

For this section I will be following Woodard’s description. According to him, Americans have been divided since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth. Colonists saw each other as competitors for people to settle their land, for the land itself, as well their ability to draw capital to their settlement. Here are some of the issues that divided the colonies:

- Loyalty to England: Royalist Virginia (Tidewater) vs Yankee Massachusetts

- Individualism: Yankees and New Netherlands were for individualism vs social reform orientation of New France

- Religion: Puritanism (Yankees, New England) vs Quakers’ freedom of conscience (Midlanders). In addition, there was a tension between the liberal and evangelical spectrum about how to practice their religion.

- Politics: The importance of politics for the Deep South and the Yankees as opposed to apathy to politics of the Quakers (Midlanders)

- Use of force: Active use of force by Tidewater, the Deep South and Appalachia vs Midlanders, (Quakers) non-violence.

- Secession: Not only Tidewater and the Deep South, but Appalachia and New England also considered secession.

These regions had differences in religion between Catholics, Puritans, Anglicans, Quakers and Mormons. Each region differed in the kind of work people did, from cattle rearing, hunting, fishing, fur trapping, agricultural capitalism (producing tobacco, sugar and cotton), subsistence farming, herding, and industrial production (mining, railroad work and smelting). These regions were formed with different intentions including for religious purposes, commercial purposes, political independence or as a home for refugees. The politics of the regions differed drastically, from authoritarian (Deep South) to egalitarian (New France) to liberal (New England town-hall and the Left Coast) to classical republican (Tidewater) to libertarian (Far West).

Regionalists in the U.S. respected neither state nor international boundaries. It was only when England began to treat these colonies as a single unit and implemented policies that threatened them all, that they formed a united force. It is important to realize the uniting against an enemy does not create unification after the confrontation is over. After all, the greatest regional battle in US history occurred almost a hundred years after Independence Day.

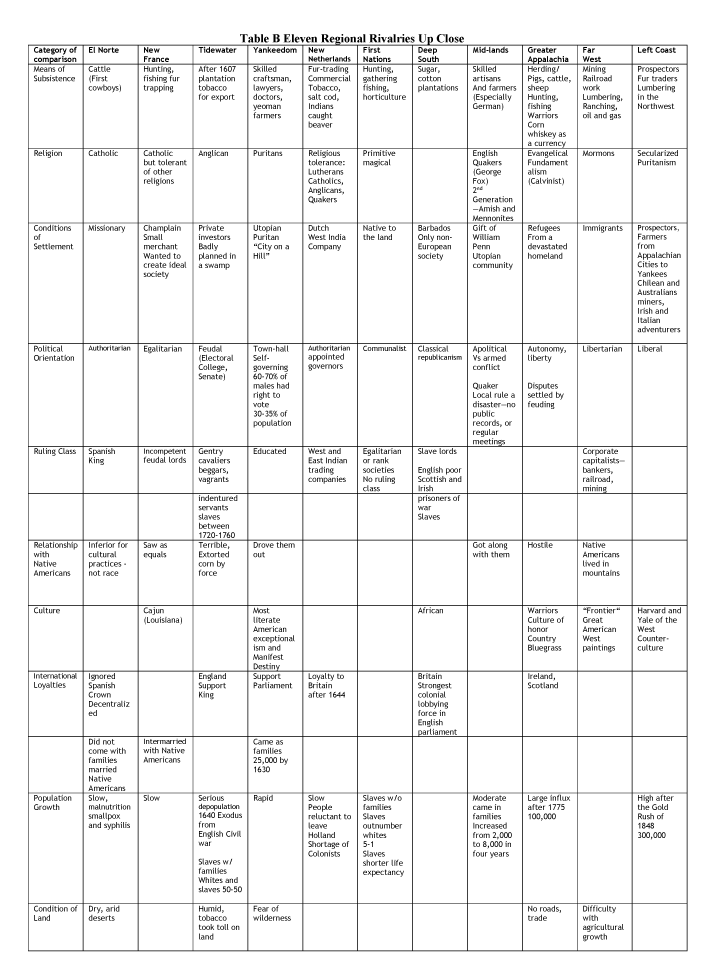

Woodard points out that Americans are one of the only countries in the world who do not make a distinction between a statehood and nationhood. A state is a sovereign political body that monopolizes the means of violence. A nation is a group who share a common culture, ethnic origin, language, historical experience, artifacts and symbols. Some nations are stateless like the Kurdish, Palestinians and Quebecers. Most agricultural states such as Egypt, China, Mesopotamia and India had states without being a single nation (Anthony D. Smith’s work is great for these distinctions). Using these criteria, the regions of the country are like the “nations” of America. Americans may have a federal state, but not a single nation. Before turning to the predominant struggle between regions, Table B contains a close-up of the differences between all eleven regions.

Neither the American Revolution Nor the Civil War United the Regions

Neither the American Revolution Nor the Civil War United the Regions

It is tempting to think that the revolutionary war against England united the regions. This is far from true. Native Americans fought on both sides of the revolutionary war. It was the New England Yankees that were the backbone of the revolution. New Netherlands was the stronghold of the loyalists after England drove out the Dutch. In the Midlands:

The region would not have rebelled at all, if a majority of the states attending the Second Continental Congress hadn’t voted to suppress Pennsylvania’s government (132)

Until the battle of Lexington, the Deep South was torn as to who to join until it was rumored that the British were smuggling arms to the slaves. It was the prospect of freed slaves that made them fight the English. Southern Appalachia fought on the side of the English and lost.

Neither did the Civil War pulverize the regions into two. Woodard says that the Civil War was a conflict between two coalitions of the Deep South and Tidewater against the Yankees. The other regions wanted to remain neutral and were considering breaking off into their own confederations

The Conflict Between the South and the East Prior to the 19th Century

Slave aristocracy of the Deep South

To begin with, there was an aristocracy in the thirteen colonies but this aristocracy did not rule over peasants who did subsistence farming. The plantation owners of the South ruled over slaves who produced commercial goods of sugar, tobacco and cotton for a world market. In the East, there were university educated professionals of lawyers and clergy(“Brahmins”) who joined with merchants attempting to develop home industry (rather than trade with England, as the plantation owners did.)

All regions are not economically equal

While all eleven regions had their conflicts with each other, some regions were settled longer and they concentrated more economic wealth at their disposal. For example, the mountain people Appalachia herded sheep, pigs and goats. They were in no position to compete for cultural dominance with the planters of Tidewater or the Deep South. The settlers of what became known as New France made their home in Canada and in Louisiana. They were fisherman, fur-trappers, and hunters. They could not compete with the Yankees of the Northeast or the fur traders of New York. Even those with capital who settled late, as in the Far West, did not have centuries to build up a culture the way those in Tidewater, the Deep South, Yankeedom and New Netherlands did. These regions had over a 200-year head start.

What does it mean to be an American?

When we compare the civilizational processes of the United States, we are really talking about the differences between the New Englanders, New Netherlands and Midlands and to a lesser extent, Appalachia. It is from these regions that the concept of an American grew. In the case of the other regions, El Norte was long abandoned by the Spanish and New France by the French. Both these regions were inhabited by people who never accumulated capital. Native American tribes were decimated. Tidewater and the Deep South are not cultures which are termed “American”. While the Far West and the Left Coast certainly had wealth, they were settled too late to have civilizational impact.

There is a reason I am focused on the initial time of first settlement and not discussing these regions all the way to the present. It has to do with Wilbur Zelinsky’s “first effective settlement law”which says:

Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to affect a viable self- perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settler may have been. (American Nations, 16)

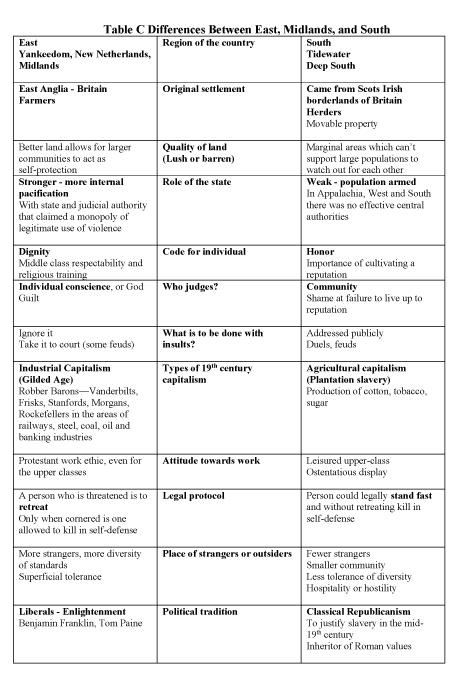

The fundamental arena in which American civilization played itself out, is between Tidewater and the Deep South on the one hand, and the Yankees and New Netherlands on the other. Civil War historians might call this the battle between the “North and the South”, but this crudely lumps the eleven regions we discussed into two. The people of Appalachia might technically be in the South but they always had animosity to the planters. The Midlanders of the North might have sided with Yankees and New Netherlands against the slave traders, but they were not industrial capitalists who had a material interest in luring poor farmers into their factories. Therefore, there are two processes of being civilized in the United States, one southern and the other East and Central parts of the United States.

Culture of honor in Colonial South

Roger Lane, in his book Murder in America: A History, traced the major differences between the North and the South to a southern “culture of honor” that did not exist in the North. But where does this culture of honor come from? Lane argues that the process begins when we examine the differences in the kinds of work people did in the regions of England that they came from before settling in America. The inhabitants of Tidewater came from the Scotch-Irish borderlands of Britain where they engaged in herding. With moveable property, herders always had to be on guard, otherwise their animals might be stolen. Because herding was a difficult life, herders were not competing with many other herders for grazing ground. The sparseness of the settlement pattern makes it difficult for herders to rely on others to protect their land.

Lastly, in both the borderlands of Britain or the areas of Virginia in which they settled, there was no centralized state to act as law enforcement. Under these conditions, herders develop very rigid protective mechanisms, being suspicious quickly, while reading body language for potential thievery. The culture of honor occurs when people cultivate a trust among equals. A culture of violence is the result of what happens when the culture of honor is violated. Someone who does not stand up for themselves has a sense of deep shame among herders. He has a reputation to defend. If insulted, the insult is addressed publicly in a duel or family feud.

Culture of Dignity in the Colonial North

On the other hand, the New England farmers came from East Anglia in England where farming was practiced. Farming lends itself to living in close quarters, thus providing a social protection against theft. In addition, once they settled in New England, they lived near large cities and under the rule of law. This meant there was some legal ground for recovering stolen property. These conditions meant that farmers did not cultivate suspicion and a code of honor. Consequently, they were less likely to kill as a result of stolen property. Rather, the farmer cultivated a sense of “dignity” based on universal rights. These farmers were more likely to be self-constrained and feel guilty over imagined violations over God’s law. Violations are less likely to be settled publicly. Farmers do not engage in duels. Though farmers have been known to engage in family feuds, farmers are just as likely to bring their case to the law, depending on the region of the country and the social class of the farmer.

The South and the East in the 19th Century

By the 19th century, the capitalist interests in New England and New York area had crystalized into an investment in industry, building factories for textiles and railroads for transport. This form of capitalism was irreconcilable with the plantation economy of the South. As mass commodity production spread and geographical mobility of workers increased, it became more and more important that consumers were able to get along with strangers as they bought and sold goods. What being “civilized” in the East meant to treat strangers with an even-handed polite indifference or “tolerance”. It was also civilized for industrial capitalists to have same values as the Puritans: hard work, punctuality, planning and investing. In the East, the industrial capitalists were liberal politically. To be conservative in the North in the 19th century had more to do with holding on to rural, Puritan traditions.

The plantation owners in the South had very different notions of what was civilized. In plantation life, most everyone knew everyone else and among other plantation owners there was a culture of honor which carried over from their south English heritage. Between plantation owners and slaves there was a deep expectation of deference. Encounters with strangers were much more loaded. While the Eastern cities cultivated a cool indifference to strangers, in the South what was civilized was “southern hospitality”, which meant bringing hospitality to a stranger. This meant being generous with time, food and culture. But strangers who, for whatever reason, were not candidates for southern hospitality were not ignored. They were driven out or killed.

Southern gentleman planters, like their aristocratic brothers in Europe, had a contempt for hard work and Puritanical values. What was civilized to them was the cultivation of taste in the arts, in manners and in clothing. For them, being civilized meant to enjoy life and display wealth. Politically, the Southern planters justified their existence as classical republicans who believed that liberty was only for the upper classes. They were contemptuous of the Enlightenment value of science and technology and saw themselves as the inheritors of Roman values. Please see Table C for a summary of these regions.

Manners in the East, the Midlands and Appalachia

Manners in the East, the Midlands and Appalachia

Tocqueville famously commented that on one hand, Jacksonian America was far more egalitarian than anywhere in Europe, and less deferential. However, there was more bragging. His explanation was because of a lack of clear class boundaries, people bragged as a way to establish a status of which they remained unsure. According to Stephen Mennell, (The American Civilizing Process) both Hegel and De Maistre commented on the lack of manners in America. Baudelaire described America in the 1850s as “a great hunk of barbarism illuminated by gas… a construction of hardened chewing gum and idiotic folklore.” Complaints about Americans chewing tobacco were common by Europeans. By the mid-19th century, Europeans also commented on what they saw as a general American obsession with cleanliness. But Yankees weren’t always like this.

Those who washed daily did so at the kitchen sink. Soap was mainly used for laundering clothes. By the 1830s, the bathtub and daily bath were beginning to spread beyond the very rich. Immigrants new to cities were taught by social workers, educators and employers how, where and how often to bathe with soap and warm water (66). In 1840, only a tiny minority of the wealthy city-dwellers had running water and flushing water closets in their homes (65). (The American Civilizing Process)

According to Mennell, books about American manners penetrated deeper into the class structure, in part because of the lack of the English social elite in the colonies to draw inspiration from and because a higher number of lower-class people could read.

How Did Frontiersmen See Eastern and Midlands Civilization?

Mennell says that the following stereotypes were common among frontiersman about people in eastern cities. The East was seen as decadent, whereas the frontier was pristine. The East was mired in interdependent social ties such as proletarians linked to wage labor and factories in cities. The frontier, on the other hand, was the home of independent hunters, fur-trappers, ranchers or miners who called their own shots. While the East was the home of elite bankers and industrialists, there was a rough social equality on the frontier.

But what does living in a country with a frontier do to the civilizational process? Turner, in his book The Frontier in American History, traced the steady penetration of the frontier westward from the eastern seaboard in the 17th century all the way to the Rocky Mountains in the 19th. century. He distinguishes three phases:

- the traders’ frontier—characteristic of French colonization and fur trade

- the miners’ and ranchers’ frontier of the West

- farmers’ frontier—which left the trademark of the English in the Midlands

Turner argued that the constant availability of free land meant that Americans would be less in danger of creating elite hierarchies because these hierarchies would be broken up since there was a constant return to more primitive conditions.

The Uncivilized Nature of the Frontier

According to Mennell, when people who have been socialized in more settled conditions are cast out into the margins of society, their behavior will change. The behavior will become more blatantly self-interested if they can get away with things that they couldn’t get away with under more settled conditions. This behavior will become even more confrontative if, because of the rough balance of power, calculations of what will happen are less predictable. These higher levels of danger will produce emotions that are more impulsive and more violent, just as Huizinga claimed occurred during the European Middle Ages.

According to historian Patricia Limerick, the image of the self-reliant and individually responsible pioneer was not supported by her research account that outside of every farm in the 1880’s stood a great mound of empty food cans. She further pointed out these “self-reliant” pioneers often blamed the federal government for their problems along with everyone else.

The consequences of the frontier process, according to Turner, were that:

- The westward move diluted the predominantly English character of the eastern seaboard.

- The advance of the frontier decreased America’s dependence on England for supplies.

- It helped to develop the central government. The very fact that the unsettled lands had been vested in the federal government was vital to the federal government’s battle to control recalcitrant regions of the country.

The Western Frontier as Yankee romanticism

As Richard Slotkin warns us, we must distinguish between the people who actually lived on the frontier—hunters, trappers, miners, gold prospectors – and how the frontier was portrayed in American literature, as in dime-store novels and the work of Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales. We are interested in how the frontier romance in literature was a way for readers to:

- escape the dark side of the industrialization process;

- escape the increasingly militant class struggle taking place between New England, Yankeedom on the one hand and the southern plantation owners on the other;

- muffle the class struggle in industrialized cities in hopes that the frontier stories could provide an outlet.

In the United States, the rebellion against civilization was directed not at an aristocratic class but at lawyers, merchants, industrialists and bankers of the East. Whatever their dissatisfactions were with relentlessness of the industrialization of the cities, it did not result in a romantic, organic view of nature as in Europe. In Europe, during the romantic period, many nation-states claimed their roots in more primitive peoples, whether they are Anglo-Saxons or Celts. But for Puritans, the heathen Native Americans were out of bounds as people to go back to nature with. To return to the pristine way of life was to adapt the way of the savages, which for them would be “hell on earth”. Puritans bitterly condemned those who “went native” and lost their souls.

While aristocratic romantics of Europe used tame country scenes to trigger collective memories of by-gone days, in the New World, what was romantic was pristine, wild and like the subtle paintings of the West by Remington and Thomas Moran. While romantics in Europe took the occasion to delve into the pre-modern world of the peasantry through the study of language and folklore, writers on American romanticism did not do this. In America, there was a deep anti-historical sense, and what appealed to romantics was the exotic world of mountains, rivers and forests that have not been seen before. In addition, the frontier was about trappers, hunters and miners who were half-way between Eastern decadent civilization and the “savagery” of the native Americans. Stories about the frontier were about Puritan’s “errand into the wilderness”. Puritans were terrified of the savagery of native Americans. Their roots were in Puritanism, not in knowing more about native culture that was from a non-Christian world.

In the New World, the sources of romanticism were men of action, men who fought Indians, gambled and blazed trails. Different frontiersman represented different regions of the country and utilized different means of subsistence. For example, stories about Daniel Boone took place in Kentucky, Tennessee and Missouri. The stories of Kit Carsen were those of a fur trapper of the mountains. Stories about Davy Crockett were more about the frontier in the Southwest.

What romantics on both sides of the Atlantic had in common was a refusal to play roles. This was certainly true of the frontiersman attitude towards the ways of the East. Additionally, both kinds of romantics refused to act in ways that demonstrated they were civilized. While in the United States there was a championing of what was wild, unpredictable and dangerous, this did not lead to identification with mental illness as the romantics did in Europe. However, the romanticism of outcasts in the wild west, such as gun fighters like Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, and Buffalo Bill was taken way beyond Europe. The glorification of the frontier, the west and the cowboy hasn’t let up even in the 21st century!

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to show the deep political and economic fault-lines of the eleven regions of the United States. We began with eight questions about how the time of settlement, the country of origin, geography, religion, population density, attitudes to immigrants and natives might affect how these regions felt about each other. Where in the country would the greatest tensions between the regions be? What regions had the most in common where alliances could be formed? We then named six topics which were the deepest tension point in the regions. These tensions are hardly cosmetic. They remained throughout both the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.

We then turned to the conflict between Tidewater, the Deep South, Appalachia and Yankees as the central struggle in the United States. Being an “American” was forged between four regions—Yankeedom, New Netherlands, Midlands and Appalachia. I closed my article with our focus on the West. This included how frontiersman themselves viewed the East as decadent and how writers of the East romanticized the West in dime store novels and paintings.

The United States of America is hardly united, nor has it ever been. The real physical economy today is hammered by lack of investment and lack of work due to COVID. Meanwhile finance capital continues to destabilize the economy with the mania of printing free money. As extreme weather pounds the regions from Florida to California and from Texas to North Dakota, it would be hardly surprising that as Anglo-American capitalism sinks into the bog, that part of the sinking will involve a fracturing of the regions in a good ole American style, with each region for itself, and the Devil taking the hindmost.

• First published in Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism

The post Divided We Stand: Eleven Regional Rivalries from Mountain People to the Swamps of Dixie first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.