This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The World Health Organization has completed the first phase of a critical polio vaccination campaign in central Gaza. After health officials confirmed Gaza’s first polio case in 25 years, the Israeli military agreed to calls for limited humanitarian pauses on its attacks in order for aid organizations to carry out vaccinations. But “there’s real practical, operational problems with this current pause,” says Yanti Soeripto, president and CEO of Save the Children US, whose staff is part of the vaccine drive. “It is not a ceasefire at all. It is an eight-hour pause every day.” As Israel has repeatedly attacked civilians awaiting the provision of aid over the course of its war, it is “difficult to reach normal coverage numbers” — especially for the two-dose vaccine course necessary to vaccinate against polio. Soeripto also discusses outbreaks in other current war zones, including the recent outbreak of mpox in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and warns that “these diseases often cause even more casualties than bombs and bullets.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

We get an update from Gaza, where at least 68 Palestinians have been killed in the last 24 hours as Israel continues its relentless assault on the territory. After nearly 11 months of war, the official Gaza death toll now stands at over 40,600, although the true figure is estimated to be much higher. The World Food Programme announced it is pausing the movement of all staff in Gaza until further notice after Israeli forces shot at one of its clearly marked vehicles despite receiving multiple clearances by Israeli authorities. This comes just two days after U.N. humanitarian efforts in Gaza virtually ground to a halt due to new Israeli evacuation orders that disrupted operations again. Israel has issued several evacuation orders across Gaza over the past week, displacing a quarter of a million people in Deir al-Balah alone, including from the Al-Aqsa Hospital, where tens of thousands of residents and wounded were seeking shelter. Journalist Akram al-Satarri, speaking from just outside the hospital, describes “continuous military operations, continuous devastation, continuous targeting and [an] increased number of Palestinians affected by those ongoing operations either by being killed or being injured or by becoming displaced because of the new evacuation orders.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Biden administration will send about $125 million in new military aid to Ukraine – August 23, 2024 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A Thai pledge to donate millions of baht to help alleviate a humanitarian crisis in neighboring Myanmar has met with a mixture of gratitude and skepticism from Myanmar’s pro-democracy government in exile.

The kingdom will give nine million baht (US$250,000) to the humanitarian center of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, known as ASEAN, Thai Foreign Affairs Minister Maris Sangiampongsa told a regional meeting in Laos on the weekend.

But Kyaw Zaw, spokesperson for the president’s office of the National Unity Government, or NUG, said that while they greatly appreciated Thailand’s gesture, coordinating with the junta alone was not enough to ensure the aid would reach those most in need.

“Since most of the desperately in need internal [displaced people] are living in resistance-controlled areas, not the junta,” he told Radio Free Asia on Wednesday. “The coordination with the junta will just give them the photo opportunities and not effectively reach out to the desperately in-need people on the ground.”

ASEAN has been struggling to help fellow member Myanmar resolve a bloody crisis triggered by a 2021 military coup, pressing all sides to accept a plan aimed at ending the violence and initiating talks.

But Myanmar’s military has largely ignored the plan and fighting between junta forces and various allied insurgent groups has intensified this year, with the number of internally displaced rising to more than 3 million civilians, according to the United Nations.

Since forming its humanitarian corridor into eastern Myanmar in March, ASEAN’s Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management, or AHA Centre, has overseen a Thai shipment of 4,000 aid packages into Kayin state to assist civilians affected by fighting.

The AHA Centre has also distributed nearly US$2 million worth of food and hygiene supplies to communities in Myanmar’s Sagaing and Magway regions, as well as southern Shan state and Mon states, ASEAN said in a statement on Saturday.

The earlier Thai aid was initially sent over the border into a part of Myanmar under the control of junta forces and was then transported deeper into the interior.

Thai officials at the time declined to be drawn into a debate on whose territory the aid ended up in but the NUG believes such donations have failed to target populations that are the most seriously affected by conflict.

Political analyst Panitan Wattanayagorn shared that view.

He told RFA that Thailand’s initiatives regarding Myanmar were not as clear as they were in the past, including the potential use of the humanitarian corridor, because the delivery of aid had become more complicated as the control of territories changed as the course of the war unfolded.

“More and more areas are under control of groups that can deliver the support, like the Karen and others,” Panitain said. “Thailand’s participatory role is changing. It’s adopting a more maybe wait-and-see approach, unlike the previous administration.”

Parts of western Myanmar have seen critical food and healthcare shortages as junta blockades as part of its effort to battle the Arakan Army insurgent force, which has captured at least nine townships in Rakhine state and one in neighboring Chin state.

RELATED STORIES

Myanmar’s civil war has displaced 3 million people: UN

ASEAN special envoy to meet Myanmar junta leader

ASEAN should admit defeat over Myanmar

Edited by Taejun Kang.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Kiana Duncan for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

International aid group Médecins Sans Frontières, or MSF, has withdrawn from three strife-torn areas in western Myanmar, where fighting between ethnic minority insurgents and junta forces has trapped more than 10,000 civilians.

The French non-governmental organization, also known as Doctors Without Borders, said on Thursday it had been forced to pull out of three townships in Rakhine state because of the violence and restrictions on its humanitarian work.

More than 10,000 civilians have been sheltering in a school in Maungdaw town for two months. Some of them told Radio Free Asia this week they had extremely limited access to hospitals, medicine and food.

Clashes between junta forces and the Arakan Army insurgent group, which is battling for self-determination in the western state, have surged since late last year. The fighters, who have made progress against the military, have said they aim to capture Maungdaw town.

Because of the fighting, northern Rakhine state’s population, many of them members of the persecuted mainly Muslim Rohingya minority living in camps for the internally displaced, have faced travel bans, junta conscription under threat, blockades and shortages of water, medicine and food.

————————————————————————————————

RELATED STORIES

‘Neither hospitals nor doctors’ for 10,000 displaced in Myanmar

Myanmar’s displaced tell their stories on World Refugee Day

Arakan Army tells residents to evacuate ahead of attack on western Myanmar city

————————————————————————————————–

One person sheltering in the school in Maungdaw said MSF’s withdrawal could be devastating.

“It may cause a lot of difficulties. How can people injured by the bomb blasts get access to medical treatment if they lose access to medical care from them?” said the residents, who declined to be identified for safety reasons.

“We have absolutely no access to medical treatment,” he said.

Getting to the MSF office had already become increasingly dangerous because of the fighting in the town, the resident said.

“The office is in Ka Nyin Tan neighborhood and even residents of Ka Nyin Tan are on the run due to so many shells landing there,” he said.

The junta has banned all transport of medicine since the fighting with the Arakan Army resumed in Rakhine state in November. The ban was aimed at insurgents getting medical care. Junta forces have shut down and bombed hospitals, but the result has been that many civilians have died , residents said.

MSF said it had been unable to provide regular health services in the central and northern parts of Rakhine state since November.

On April 15, its office and medicine storage facilities in Buthidaung township were destroyed by fire. Since then, other private and public health services have been unable to operate in the area, MSF said in its statement.

Warehouse blaze

In Maungdaw, other humanitarian groups have also encountered disruption to their operations. On Tuesday, the World Food Programme, or WFP, announced its warehouse in Maungdaw township had been burned down.

The Arakan Army, in a video released on Tuesday, accused the junta army and affiliated groups of breaking into and looting the warehouse on June 21. The junta denied that accusation.

Junta spokesperson Maj. Gen Zaw Min Tun told the junta-controlled Myanma Alin on Thursday that the warehouse had not been vandalized, and he accused Rohingya of stealing food from it. The newspaper said the Arakan Army had burnt the warehouse down with a drone attack.

Junta forces delivered the WFP food aid to families in need on June 22, Zaw Min Tun told the paper.

“The rice bags intended to support the displaced people were delivered to more than 2,000 households in neighborhoods 1, 2, 3 and 4, as well as Ka Nyin Tan and Maung Ni neighborhoods by the military council’s security forces,” he said. “One rice bag per household was distributed.”

However, the junta said in a statement on Monday that the Western Region Military Headquarters and departmental officials had delivered more than 2,000 rice bags, but did not mention any affiliation with the WFP.

RFA could not confirm that the sacks of rice seen being distributed in photographs provided by the military had any WFP labels on them.

The WFP said in a statement, the warehouse contained enough emergency relief food to feed nearly 65,000 people for a month.The organization has been unable to travel to Maungdaw since May.

Translated by RFA Burmese. Edited by Kiana Duncan and Mike Firn.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Asia Pacific Report

New Zealand activists Youssef Sammour and Rana Hamida have been selected to join the volunteer crew on the international Freedom Flotilla ship Handala, currently visiting European ports and heading to break Israel’s siege of Gaza.

They will be farewelled at 10:30am upstairs at the Auckland International Airport on Sunday, reports Kia Ora Gaza.

Trevor Hogan, a former Irish rugby champion and pro-Palestinian activist who participated in several flotillas that were water cannoned and pirated by the Israeli military in the past, has sent a special message to the volunteers and those supporting the freedom missions in “a time of great, unquantifiable grief”.

“While our Handala has just left the Irish port of Cobh and we continue to work on reflagging the flotilla ships stuck in Istanbul, the decades of solidarity from Ireland remains palpable, unwavering and tremendously significant for Palestinians and the wider diaspora,” said Kia Ora Gaza.

“This is a reminder to everyone watching: on those dark days, take time to regroup, regather, and come back again. Until Palestine is free.”

Trevor Hogan’s message to the world in support of Palestine. Video: Freedom Flotila Coalition

Concerns raised over US ‘floating pier’

Meanwhile, Ahmed Omar in Monoweiss reports that in March 2024, US President Joe Biden announced in his State of the Union address that the US would be building a temporary “floating pier” on the Gaza shoreline to deliver “humanitarian aid” to the starving population in Gaza.

“No US boots will be on the ground,” he promised.

Since then, however, critics have raised concerns that the pier is not only being used for “humanitarian” purposes but is being employed for military activities that aid in the ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza.

An intelligence source from within the resistance in Gaza, who spoke to Mondoweiss under conditions of anonymity, said there were mounting signs the US pier could also be used to forcibly displace Palestinians.

This would provide an alternative to the original Israeli plan of forcing Palestinians into the Sinai, which was rejected by Egypt early on in the war.

“The floating pier project is an American solution to the displacement dilemma in Gaza,” the source said.

“It goes beyond both the Israeli solution of displacing Gazans into Sinai . . . and the Egyptian suggestion of displacing [Gazans] into the Naqab [desert].”

Instead, the source said, the US pier would be used to facilitate the displacement of Gazans to Cyprus, and then eventually to Lebanon or Europe.

These concerns have been brought into sharp relief after the Israeli army committed a massacre in Nuseirat refugee camp last weekend, killing at least 274 Palestinians in order to retrieve four Israeli captives.

The US pier was at the centre of coverage of the massacre, as multiple news sources, videos, and eyewitness accounts from Gaza indicated that US forces may have been involved in the operation and that humanitarian trucks entering Nuseirat were hiding the Israeli soldiers that carried out the massacre.

Reported in collaboration with Kia Ora Gaza.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by APR editor.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“HUNGER CATASTROPHE IN GAZA – DONATIONS NEEDED” cries Mercy Corps.

“URGENT: STARVATION IN GAZA: ALL GIFTS MATCHED FOR GAZA” shouts Rescue.org.

These and many other appeals from international relief organizations have motivated untold numbers of compassionate and generous souls to open their purses. You may be among them. If so, you may have thought that these organizations are delivering food, medicine and other relief supplies to Gaza. But they are not.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) confirms that not a single truck with relief aid has crossed the border from Egypt to Gaza since Israeli troops captured the Rafah border crossing on May 7, 2024, more than a month ago. Until then, the Rafah crossing was the only one open. Today, roughly 1800 mostly large 18-wheel trucks, each carrying up to 12 tons of supplies, are backed up into the Sinai Desert, waiting for Israeli permission to enter. Some have been there for months. And some of those trucks belong to the relief organizations. But they, like all the others, are not getting in.

Many of the organizations also announce that, thanks to your donations, they have provided hundreds of thousands or even millions of meals to starving Palestinians in Gaza. What they do not necessarily tell you is that they are doing this by purchasing food and medicine from the dwindling supplies inside Gaza.

The bottom line is that your money is reaching the relief organization’s operations in Gaza, but food, water and medical supplies are not. The amount of food in Gaza is dwindling, and Israel is allowing only a tiny trickle to enter by isolated air drops, a single delivery by sea and occasional vehicles through the Erez crossing between Gaza and Israel. For a pre-October 7th population of 2.3 million, this is nothing.

As the supplies shrink inside Gaza, the prices rise, and your donations increase the prices further. The same applies to all the needs of the population. More money chasing fewer goods. At some point, no amount of money will buy food or medicine in Gaza. Already, Palestinians are dying of starvation, malnutrition and diseases caused by reduced resistance. These are not often reported, because they are not victims of violent slaughter, and because the hospitals, clinics and mortuaries that would have reported them to the Ministry of Health – who would have tallied them – no longer exist. The Ministry of Health barely exists, while the weak die anonymously, buried by their families and communities. Some estimates of such casualties are already in the hundreds of thousands.

It’s not that the relief agencies are not performing a worthwhile service. They are enabling increasingly scarce supplies to reach larger numbers of destitute people while they last. But they will not last, and the relief organizations are unable to bring additional supplies. Furthermore, they are mostly failing to be forthright with you by reporting these facts. Instead, they are projecting an image of success, with the result that you might think that they are maintaining a lifeline when in fact Gaza is heading to complete depletion of the few resources that remain.

This is what Israel intends. If the food is distributed equitably, a large proportion of the population will survive until the day there is nothing left. Then everyone will starve at the same time, and the genocide will be accomplished quickly with the last loaves of bread costing $1000 apiece. And the humanitarian relief organizations will not have warned you.

The post Did you donate to send food to Gaza? Think again first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – June 6, 2024 White House announces $225 million aid package to Ukraine as Biden commemorates D-Day 80th Anniversary. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

After working at the U.S. State Department for over 20 years, Stacy Gilbert quit the Biden administration this week after a report she contributed to concluded Israel was not obstructing humanitarian assistance to Gaza. Gilbert served as a senior civil military adviser in the State Department’s chief humanitarian office, which features heavily in internal policy discussions over Gaza. Despite “abundant evidence showing Israel is responsible for blocking aid,” the report concluded the opposite and was used by the Biden administration to justify continuing to send billions of dollars of weapons to Israel. Gilbert says she was “shocked” to find that the report concluded Israel was not not blocking humanitarian assistance: “That is not the view of subject matter experts at the State Department, at USAID, nor among the humanitarian community. And that was known. That was absolutely known to the administration for a very long time.” Gilbert says there is a clear pattern by Israel “of arbitrarily limiting, restricting or just outright blocking assistance going in that has caused the very grave situation in Gaza.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Things are looking dire for the Ukrainian war effort. Promises of victory are becoming even hollower than they were last summer, when US President Joe Biden could state with breathtaking obliviousness that Russia had “already lost the war”. The worst offender in this regard remains the United States, which has been the most vocal proponent of fanciful victory over Russia, a message which reads increasingly as one of fighting to the last Ukrainian.

Such a victory is nigh fantasy, almost impossible to envisage. For one thing, domestic considerations about continued support for Kyiv have played a stalling part. In the US Congress, a large military aid package was stalled for six months. Among some Republicans, in particular, Ukraine was not a freedom loving despoiled figure needing props and crutches. “From our perspective,” opines Kentucky Republican Senator Rand Paul, “Ukraine should not and cannot be our problem to solve. It is not our place to defend them in a struggle with their longtime adversary, Russia.” The assessment, in this regard, was a matter of some clarity for Paul. “There is no national security interest for the United States.”

Despite this, the Washington foreign policy and military elite continue to make siren calls of seduction in Kyiv’s direction. On April 23, the Senate finally approved a $US95.3 billion aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, with the lion’s share – some US$61 billion – intended for Ukraine’s war effort.

On April 24, a press release from US Secretary State Antony Blinken announced a further US$1 billion package packed with “urgently needed capabilities including air defense missiles, munitions for HIMARS, artillery rounds, armored vehicles, precision aerial munitions, anti-armor weapons, and small arms, equipment, and spare parts to help Ukraine defend its territory and protect its people.”

On May 14, in his address to the Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute, Blinken described what could only be reasoned as a vast mirage. “Today, I’m here in Kyiv to speak about Ukraine’s strategic success. And to set out how, with our support, the Ukrainian people can and will achieve their vision for the near future: a free, prosperous, secure democracy – fully integrated into the Euro-Atlantic community – and fully in control of its own destiny.” This astonishingly irresponsible statement makes Washington’s security agenda clear and Kyiv’s fate bleak: Ukraine is to become a pro-US, anti-Russian bastion, with an open cheque book at the ready.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has made the prevention of that vision an article of faith. While Russian forces, in men and material, have suffered horrendous losses, the attritive nature of the conflict is starting to tell. While Blinken was gulling his audience, the military realities show significant Russian advances, including a threatening push towards Kharkiv, reversing Ukrainian gains made in 2022.

There are also wounding advances being made in other areas of the conflict. US and NATO artillery and drones supplied to Ukraine’s military forces have been countered by Russian electronic warfare methods. GPS receivers, for instance, have been sufficiently deceived to misdirect missiles shot from HIMARS launchers. In a number of cases, the Russian forces have also identified and destroyed the launchers.

Russian air power has been brought to bear on critical infrastructure. Radar defying glide bombs have been used with considerable effect. On the production and deployment front, Colonel Ivan Pavlenko, chief of EW and cyber warfare at Ukraine’s general staff, lamented in February that Russia’s use of drones was also “becoming a huge threat”. Depleted stocks of weaponry are being replenished, and more soldiers are being called to the front.

Despite concerns, one need not scour far to find pundits who insist that such advances and gains can be neutralised. Michael Kofman of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace admits to current Russian “material advantage” and holding “the strategic initiative,” though goes on to speculate that this “may not prove decisive”.

The gong of deceit and delusion must, however, go to Blinken. Americans, he claimed, understood “that our support for Ukraine strengthens the security of the United States and our allies.” Were Putin to win – and here, that old nag of appeasement makes an undesirable appearance – “he won’t stop with Ukraine; he’ll keep going. For when in history has an autocrat been satisfied with carving off just part, or even all, of a single country?”

Towards that end, “we do have a plan,” he coyly insisted. This entailed ensuring Ukraine had “the military that it needs to succeed on the battlefield”. Biden was encouraged by Ukrainian mobilisation efforts, skipping around the logistical delays that had marred it. Washington’s “joint task” was to “secure Ukraine’s sustained and permanent strategic advantage”, enabling it to win the current battles and “defend against future attacks. As President Biden said, we want Ukraine to win – and we’re committed to helping you do it.”

Even by the standards of US Secretaries of States, Blinken’s conduct in Kyiv proved brazen and shameless. A perfect illustration of this came with his musical effort alongside local band, 19.99, involving a rendition of Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.”

Local indignation was quick to follow. “Six months of waiting for the decision of the American Congress” had, fumed Bohdan Yaremenko, legislator and former diplomat with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s party, “taken the lives of very, very many defenders of the free world”. What the US was performing “for the free world is not rock ’n’ roll, but some other music similar to Russian chanson.”

As for the performance itself, the crowd at Barman Dictat witnessed yet another misreading – naturally by a US politician – of an anthem intended to excoriate American failings, from homelessness to “a kinder, gentler machine gun hand”. Appropriately, the guitar, much like the performer, was out of tune.

The post Promising the Impossible: Blinken’s Out of Tune Performance in Kyiv first appeared on Dissident Voice.

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Binoy Kampmark.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A new Human Rights Watch Report finds Israeli forces have attacked humanitarian aid convoys and facilities at least eight times since October 7 despite being given their coordinates. Israeli authorities did not issue advance warnings to any of the aid organizations before the attacks, which killed at least 15 people, including two children, and injured at least 16 others. More than 250 aid workers have been killed in Gaza over the past seven months, according to the United Nations. “Aid workers, unfortunately, die in conflict zones,” says HRW researcher Belkis Wille. “What’s really unique in the context of Gaza is the high number in such a short period of time.”

Wille also discusses a recent U.S. government report that found Israel has likely violated international law in its assault on Gaza but that it could not make that conclusion definitively — a “shocking” finding, she says. “The United States absolutely has to start doing more to limit military assistance to Israel. … And it needs to do far more to protect civilians more broadly.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Aid agencies are running out of food in southern Gaza amid Israel’s ongoing offensive in Rafah and the shutdown of the two main border crossings in the south. Some 1.1 million Palestinians are on the brink of starvation, according to the United Nations, while a “full-blown famine” is taking place in the north. Meanwhile, some Israelis have been blocking aid from reaching the Gaza border, including a violent attack on trucks carrying humanitarian relief through the occupied West Bank earlier this week, when settlers threw food packages on the ground and set fire to the vehicles at the Tarqumiyah checkpoint near Hebron. “They did whatever they want,” says Israeli lawyer and peace activist Sapir Sluzker Amran, who documented the attack on the aid convoy. She says Israeli soldiers appeared to be working with the settlers, refusing to intervene. “They were just standing aside like there is nothing that they can do, like it’s normal, what’s happening.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Pacific island countries are getting an increased share of Australian foreign aid, budget documents show, as it shifts into funding infrastructure such as undersea cables and ports in response to China’s inroads in the region.

Overall, Australia’s foreign aid budget is flat and it remains one of the least generous donors in the OECD club of wealthy nations, ranking 26th out of 31 countries. The increased focus on infrastructure also means that proportionately less of the aid budget will be spent on health.

In the Pacific, the largest aid increases in Australia’s 2024-2025 government budget are directed at Fiji, where Australia will help fund a port upgrade, and Tuvalu. The atoll nation of 12,000 people last year ceded a partial veto of its foreign policy and security relationships to Australia under the Falepili Union agreement.

“If we look at this reduction in health — is this because our partners have told us they’re not that interested in health — I don’t think so,” said Stephen Howes, director of the Australian National University’s Development Policy Center.

“If we’re going to go into Fiji and tell them we are using our aid to help them expand their port, that’s because we don’t want China to do it, and that’s going to mean less funding for health,” he said at a panel Wednesday on the budget’s aid component.

China’s government has courted Pacific island nations for several decades as it seeks to isolate Taiwan diplomatically, gain allies in international institutions and erode U.S. military dominance.

Its inroads with Pacific island nations, including a security pact with the Solomon Islands in 2022, have galvanized renewed U.S. attention to the region.

The budget released Tuesday shows the government has allocated A$4.96 billion [US$3.29 billion] to aid, an increase of 4.0% from the previous year.

“Australia is delivering a record $2 billion in development assistance to the Pacific, maintaining Australia’s position as the region’s largest and most comprehensive development partner,” the budget papers said.

In real terms, the spending is flat at 0.19% of Australia’s national income, according to the Australian Council for International Development, and less than half of its level in the 1980s.

“This budget provided the government with an opportunity to show real humanitarian leadership in responding to human suffering across the world,” the council said in a statement.

“Australians see what is happening on their screens in all corners of the globe and expect their government to do more. This budget barely touches the surface,” it said.

Howes said the budget documents project aid spending to be unchanged for the next decade and beyond.

Pacific island countries now account for more than 40% of the aid budget, almost doubling from a decade earlier, at least partly reflecting government concerns about China’s role in a region that Australia has regarded as its sphere of influence.

Australia remains the single largest donor to Pacific island countries despite China’s enlarged presence in the region. At least a fifth of the Australian aid budget is spent on what Australia calls governance programs that aim to bolster democracy, anti-corruption efforts and transparency of public institutions.

For Tuvalu, Australia will provide additional funds for its land reclamation projects that aim to protect against king tides and projected sea-level rise and also contribute the lion’s share of the country’s first undersea telecommunications cable.

Tuvalu, one of the dwindling number of nations that have diplomatic relations with Taiwan, last year signed a treaty with Australia that requires it to have Australia’s agreement for “any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other state or entity on security and defence-related matters.”

In Fiji, Australia is providing budget support to the government as the tourism-dependent economy continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. It also is supporting an upgrade to Fiji’s largest bulk cargo port and its shipbuilding industry.

Papua New Guinea, with its estimated 12 million people, remains the single largest recipient of Australian aid in the Pacific at A$637.4 million. The Solomon Islands, where Australia has a security force stationed after riots in 2021, is the second largest with A$171.2 million.

The budget documents also revealed that Australia’s government agreed in December to provide an A$600 million loan to Papua New Guinea, a day after the two countries signed a defense cooperation agreement.

BenarNews is an RFA-affiliated online news organization.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Stephen Wright for BenarNews.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

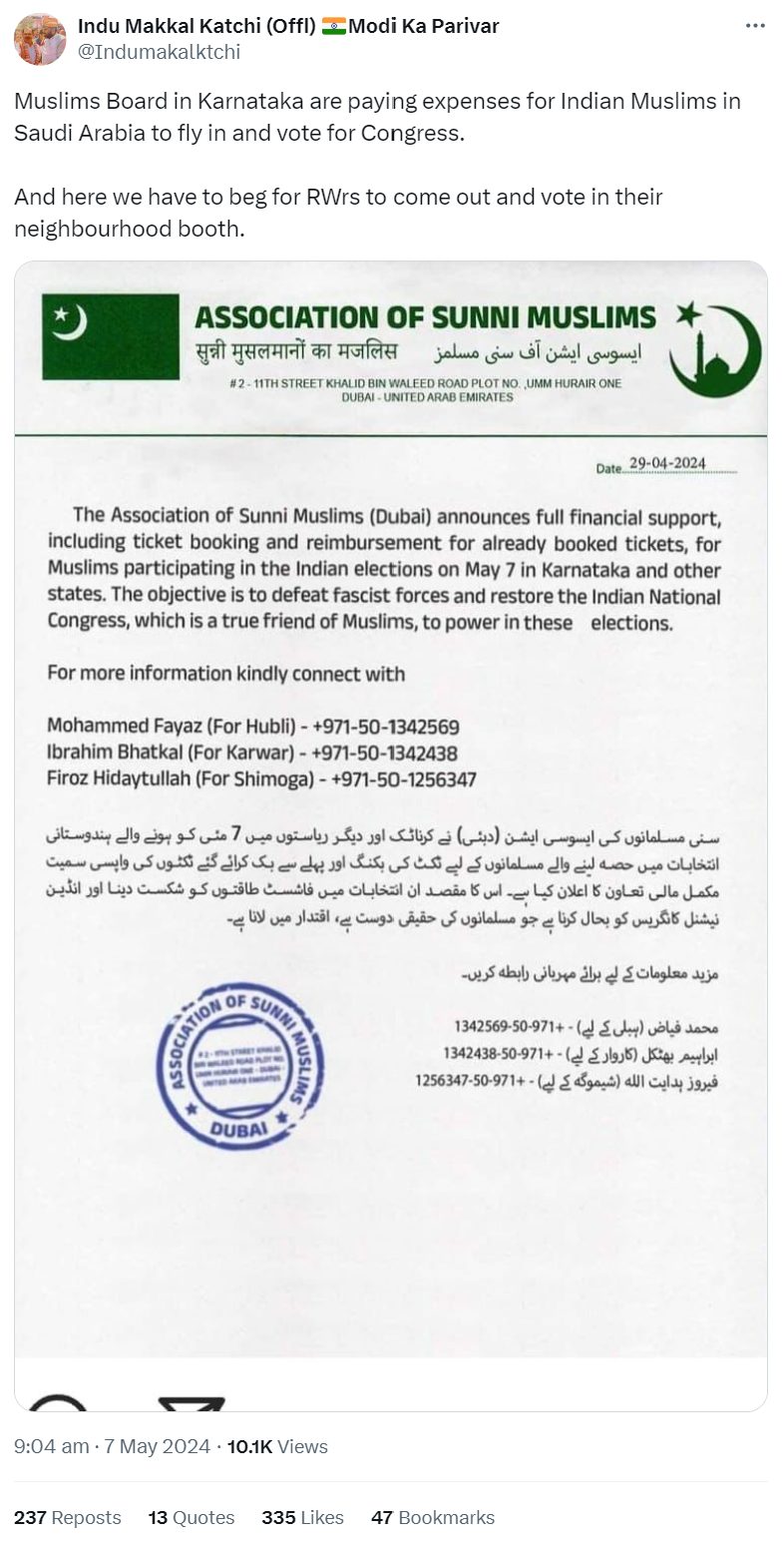

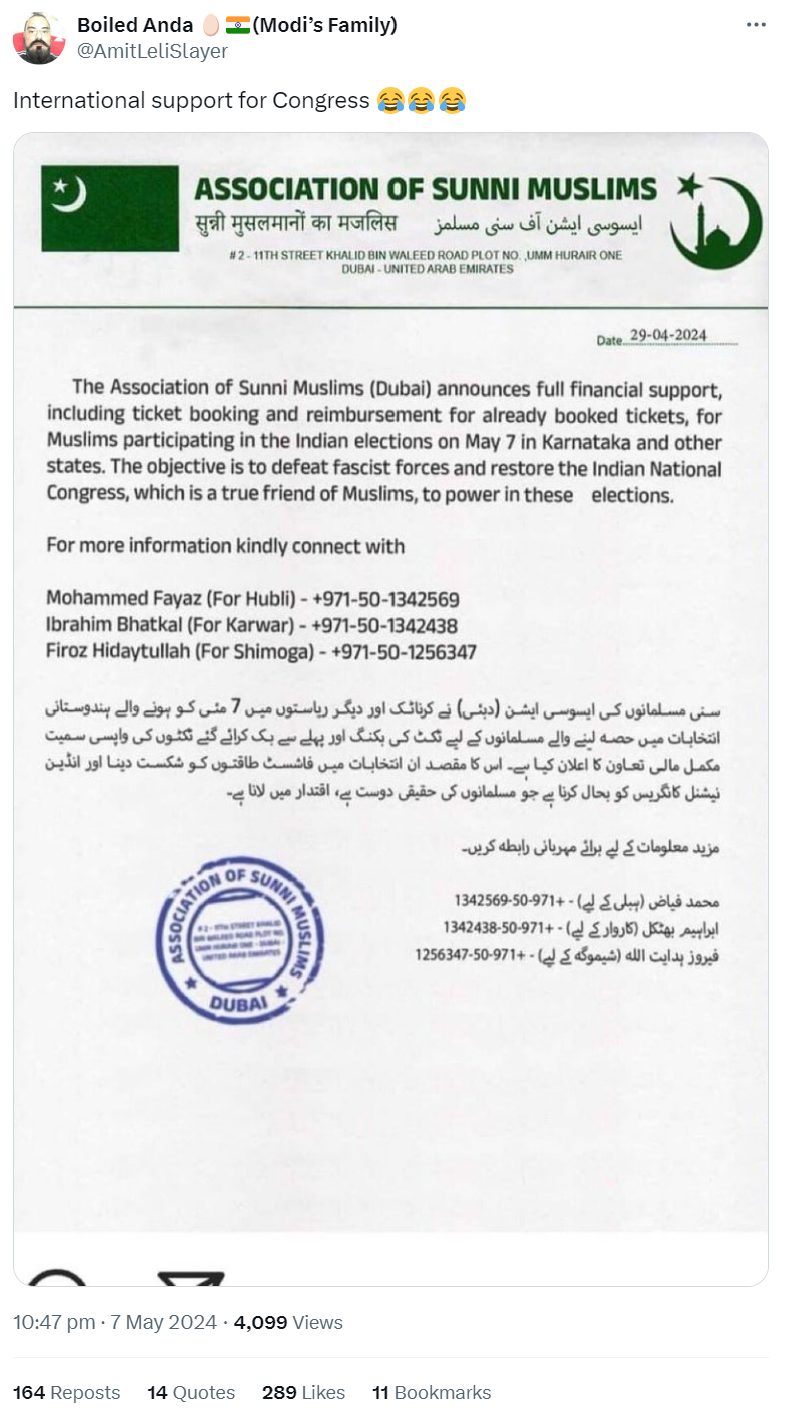

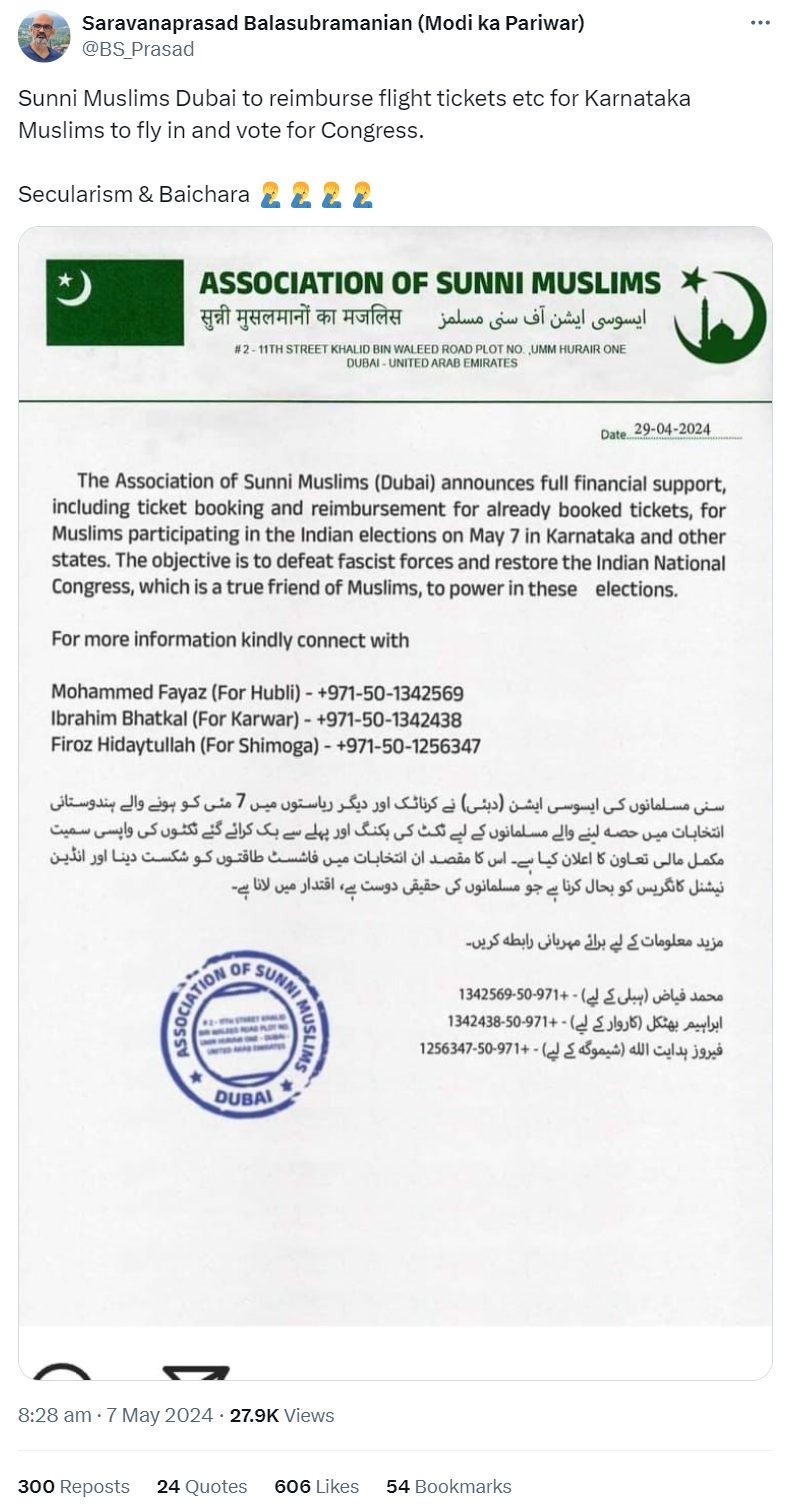

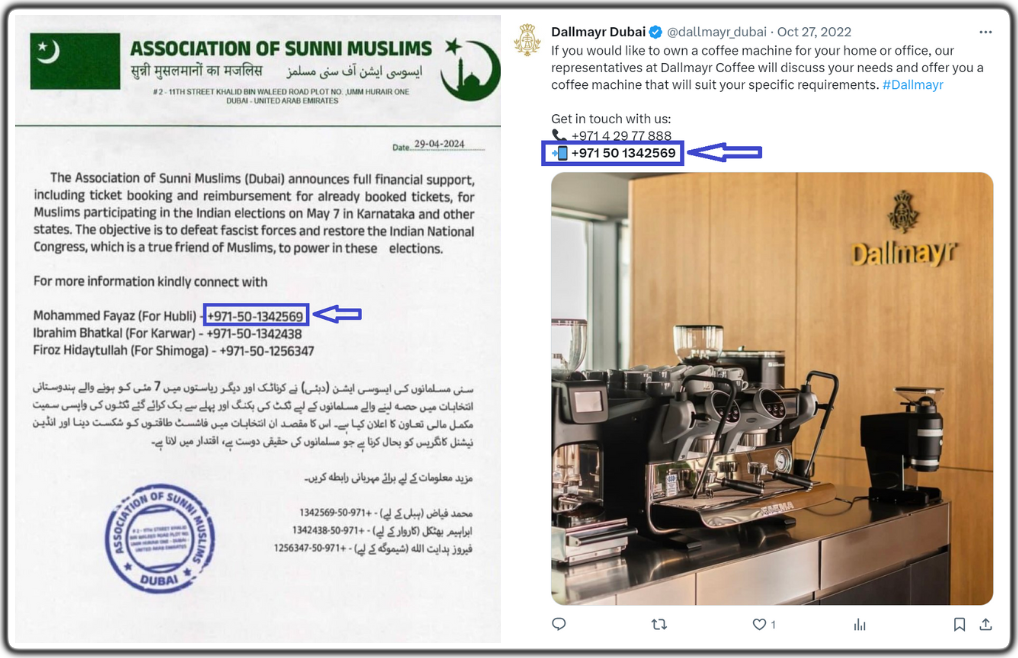

A letter has been doing the rounds on social media, featuring the letterhead of an organisation named The letter, purportedly issued by the “Association of Sunni Muslims” on its letterhead on April 29, states that the association is offering full financial support, including ticket booking and reimbursement of previously booked tickets, to Muslims travelling to Karnataka and other states to vote on May 7. According to the letter, the purpose of the assistance is to defeat fascist forces in the elections and to bring the Congress party, which “is a true friend of Muslims”, to power. The ‘letter’ is being shared with the claim that Congress is receiving support from international Muslim organisations.

right Wing influencer Arun Pudur tweeted the letter, claiming that the Association of Sunni Muslims in Dubai was providing complete financial assistance to Muslims in Karnataka to help Congress form the government. He sarcastically remarked that Hindus were either sleeping at home due to the intense heat or falsely claiming that the prime minister had done nothing for them.

An X handle named Indu Makkal Katchi also tweeted the letter, claiming that the ‘Muslim Board in Karnataka’ was spending money to get Indian Muslims residing in Saudi Arabia to vote for Congress.

A handle known to frequently promote misinformation (@AmitLeliSlayer) also shared the letter on X, claiming that Congress was receiving international support.

BJP supporter Saravanaprasad Balasubramaniam tweeted the letter as well, stating that Sunni Muslims in Dubai planned to reimburse the flight expenses for Muslims participating in the Karnataka elections on May 7 so that they could fly in and vote for Congress.

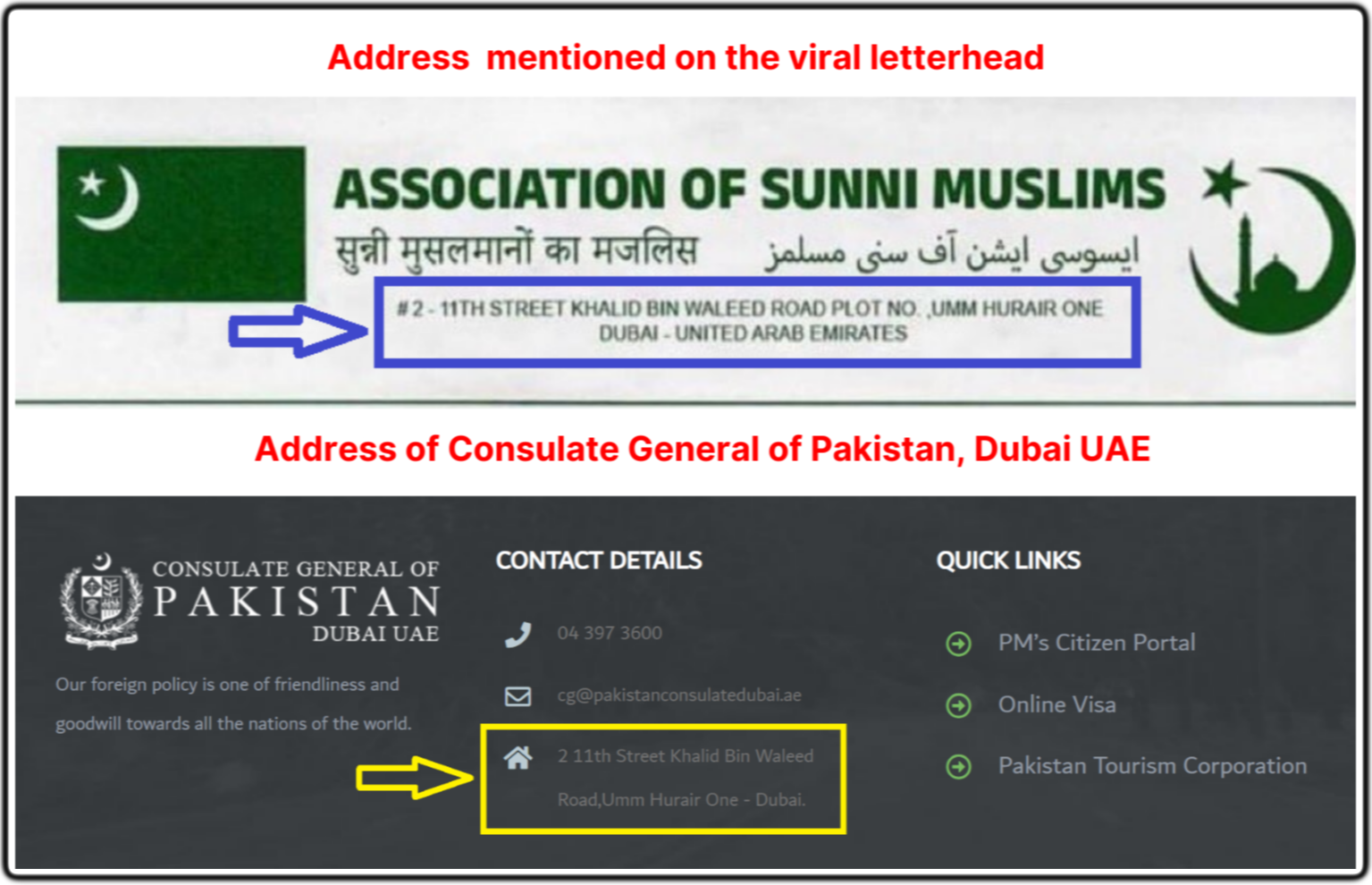

We performed a Google search and found that the address provided on the letter (#2-11TH STREET KHALID BIN WALEED ROAD PLOT NO. UMM HURAIR ONE DUBAI-UNITED ARAB EMIRATES) was listed as the office address of the Consulate General of Pakistan in Dubai on their official website. This means that this address does not belong to any Sunni Muslim organisation.

Furthermore, there was no information available on the internet about such an organisation.

This letter contains three contact numbers. When we searched these numbers, we found that the first number mentioned in the letter was shared by the company Dallmayr, a coffee vending machine manufacturer in Dubai, from its X handle. This means that this number does not belong to any Muslim organisation. We have attempted to contact the remaining two mobile numbers mentioned in the letter, and this article will be updated if we receive a response.

To sum it up, the information provided in this letter is false, and it has no connection to any organisation or appeal to Muslims. Several users have shared this dubious letter, making false claims that a Sunni Muslim organisation in Dubai would be reimbursing the flight expenses of Muslims in Karnataka to vote for Congress.

The post Letter promising financial aid to Muslims voting for Congress is not genuine appeared first on Alt News.

This content originally appeared on Alt News and was authored by Abhishek Kumar.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays – May 9, 2024 Biden Administration holds up military aid delivery to Israel over disagreement over planned Rafah raid. appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Tens of thousands of displaced Palestinians are fleeing Rafah as Israeli airstrikes and shelling hammer the eastern part of the city. Fuel, food, medicine and other supplies have been cut off following Israel’s seizure and closure of the border crossing with Egypt. The main hospital in the area has also been shut down. Over 1.4 million people are seeking shelter in Rafah, the southernmost city of the Gaza Strip. Tent camps in some parts of Rafah have now vanished, springing up again as displaced families head back north. Over 60 Palestinians were killed across Gaza, many of them in Rafah, over the past 24 hours. We get a live update from Rafah from Dorotea Gucciardo of the Glia Project, who is currently on a medical mission in Gaza. “The situation on the ground is dire. Everyone here is quite afraid. To say that there’s not an incursion in Rafah right now is patently false,” Gucciardo says. “Throughout this entire day I have heard bombs, explosions, I have heard machine gun fire, and it seems to be creeping closer and closer to where we are.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In Rafah, we speak with Gaza-based journalist Akram al-Satarri about Israel tightening restrictions on humanitarian aid, refusing a ceasefire deal and planning to invade the city where over a million Palestinians are sheltering. Israel’s military seized control of the Palestinian side of the Rafah crossing with Egypt, blocking humanitarian aid from entering the besieged territory, and trapping Palestinians under heavy Israeli bombardment. This comes after Israel also closed the Karem Abu Salem crossing in southern Gaza this weekend after a Hamas attack killed four Israeli soldiers. “Israel is not allowing the entry of the humanitarian aid to Gaza, which is perceived as a lifeline,” says al-Satarri, who reports Palestinians are “in despair” as Israel orders a third of Rafah’s population to move ahead of their invasion. “They understand that more destruction, more devastation, more death and deprivation is coming for them.” Al-Satarri also speaks about Israel banning Al Jazeera, one of the only international outlets with reporters in Gaza. “I think they want to silence Al Jazeera and they want to silence all the free media for the sake of preventing any further exposure of the things that are happening on the ground.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

Palestinian children displaced by Israeli air and ground offensive on the Gaza Strip walk through a temporary tent camp near Kerem Shalom crossing in Rafah, Sunday, Jan. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Hatem Ali)

The post UN aid agency says a Rafah incursion would put hundreds of thousands of lives at risk – May 3, 2024 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The flotilla cargo ship in Istanbul (Photo credit: Medea Benjamin)

The flotilla cargo ship in Istanbul (Photo credit: Medea Benjamin)

Two gutsy activists from the Twin Cities flew to Istanbul, Turkey April 17 to join over three-hundred others from about 40 countries on an eleven-hundred mile voyage across the Mediterranean Sea to raise awareness and bring lifesaving aid to Gaza.

Vietnam Vet and member of Veterans For Peace (VFP) Barry Riesch was nervous about signing on with the Freedom Flotilla Coalition (FFC), but felt he should try to do something for the vast majority of Gazans lacking medical care and being deliberately starved. Apart from the mission’s goal of delivering over five-thousand tons of urgently needed food, water and medical supplies (including five ambulances, and an abundance of baby formula), Reisch said he wanted to do this for his grandkids in hopes “they won’t have to grow up in a world that would ignore such a tragedy.”

Riesch has good reasons to be nervous. Since the Free Gaza Movement began in 2006, only a handful of small ships have been allowed to bring humanitarian aid to Gazans. Retired U.S. Army Colonel and former diplomat Ann Wright is a member of the 2024 FFC Steering Committee. She was a participant (resistor) on five previous flotillas that never reached Gaza. In 2010 she watched Israeli troops rappelling from helicopters onto the deck of the Mavi Marmara from a nearby boat. Ten resistors were killed and 50 more wounded after some of them allegedly tried to fight back in international waters against the Israeli invaders who were using pressurized water hoses on them. In a video, Wright gave other accounts of Israeli troops harassing and beating resistors before confiscating their belongs and taking them against their will to Israeli jails until they could be deported.

Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu contends that Israel has been unfairly targeted by resistors trying to break his country’s illegal navel blockade and bring humanitarian aid into Gaza. During a 2015 speech in Tel Aviv he told the Jewisih Agency Assembly “They send flotillas to Gaza, they don’t send flotillas to Syria. It’s amazing, this travesty of justice, this violation of the truth, the rape of truth.”

Former FBI agent and whistleblower Coleen Rowley is a member of VFP and Women Against Military Madness (WAMM) couldn’t disagree with Netanyahu more. She hopes that he and his cronies will be called to answer for their criminal behavior sooner than later. Rowley has been speaking at academic and other professional venues with an emphasis on ethical decision-making for twenty years. Before flying to Istanbul she talked over the phone with me about the “berserk Israelis” who have “shredded the law” — not only breaking the rules of the high seas for murder and kidnapping, but with their ongoing violations of international humanitarian law and war crimes on land. In a recent television interview she said “ I told people I can’t help seeing the faces of my own grandchildren (I have five grandchildren now) in the faces of these poor Gazan children who are being orphaned, starved and murdered.”

Riesch and Rowley attended intensive nonviolence training shortly after arriving in Istanbul. “The most frightening part of the training was a simulation replete with deafening booms of gunfire and exploding percussion grenades and masked soldiers screaming at us, hitting us with simulated rifles, dragging us across the floor, and arresting us” author/activist Medea Benjamin wrote in a Counterpunch article. During an April 19 Zoom meeting in Istanbul, resistors discussed their fears about the trip. One recalled a mock situation where three doctors from New Zealand laid on the floor during a seminar and instructed resistors on what to do if their heads are stepped on in the dark. Lawyers provided legal advice about separating “false authority” from “legitimate authority” along with tips for walking away from precarious situations. Despite their fears, resistors believe what they are doing not only has to be done, it is morally and legally justifiable, citing a recent ruling by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) that it is “plausible” Israel has committed acts of genocide: The court further maintains, that it is now incumbent upon citizens and governments of the world to do what they can to stop the genocide.

The location of the launch was kept secret due to Israel’s history of sabotaging boats in port and the departure dates were pushed back repeatedly because of outside pressures — mostly from the Israeli and U.S. governments. Last week the Israelis made an announcement about intercepting the flotilla that prompted Huwaida Arraf, U.S. human rights attorney and FFC Steering Committee member to say “Governments must refuse to collaborate in maintaining Israel’s illegal siege on Gaza by obstructing the flotilla in any way. We call on the governments of the 40 countries represented on the Freedom Flotilla to uphold their obligations under international law and demand that Israel guarantee the flotilla safe passage to Gaza.” Soon after, UN experts reaffirmed Arraf’s demand “As the Freedom Flotilla approaches Palestinian territorial waters off Gaza, Israel must adhere to international law, including recent orders from the International Court of Justice to insure unimpeded access for humanitarian aid.”

But on April 26, the doubts crept home. During a morning call, Riesch talked about his dwindling hopes that the flotilla would make it to Gaza “Now there’s a problem with ship flags” — this is the fourth delay.” According to Reuters, Guinea-Bissau made a decision to remove its flag from flotilla boats. Istanbul activists answered with this: “The Guinea-Bissau International Ships Registry (GBISR), in a blatantly political move, informed the Freedom Flotilla Coalition that it had withdrawn the Guinea Bissau flag from two of the Freedom Flotilla’s ships, one of which is our cargo ship.”

Riesch mentioned that frustrated resistors were already drifting away and during last night’s FFC meeting, he found out numerous other boats loaded with activists were preparing to join the flotilla in a show of solidarity, even though Israelis planned to stop them with a blockade. So, it was decided the flotilla would meet up with the blockade and wait a few days before turning around. The earliest departure time he said would be Sunday April 28 — if they could clear customs. Later that evening he sent a text saying the trip was canceled.

During a follow-up Q&A TikTok post, Wright told Benjamin that Israel always uses delay tactics before flotilla launches and the State Department invariably issues travel warnings and cautions Americans about challenging the Israeli government — especially now since the U.S. has been so openly complicit with the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Gaza. While support for the flotilla remains high from Turkish nationals, Wright strongly believes the U.S. is using economic pressures including military aid, ito derail the project in Turkey.

If nothing else, those who traveled to Istanbul succeeded in bringing much-needed attention to the plight of captive and undernourished Palestinians waiting in refugee camps for the next bombing campaign. About 45% of the people living in Gaza are children under the age of 15. So far, well over one hundred fifteen thousand Palestinians have been killed or wounded — most were women and children. It may take decades to rebuild the parts of Gaza already destroyed but for now, resistors are packing their bags — some hope to return this summer.

First row — Coleen Rowley far left and Barry Riesch third from left

First row — Coleen Rowley far left and Barry Riesch third from left

Ann Wright second from left, and Medea Benjamin second from back in Istanbul

Ann Wright second from left, and Medea Benjamin second from back in Istanbul

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.