This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Of all the sources of culture shock I might have anticipated after my partner and I bought a home in 2022 in northern Italy, trash collection never crossed my mind. I didn’t know going in that Italy had become the top overall recycling country in the EU and one of the best for household-level recycling — in part by relying on those households to do a lot of the work. I quickly got my crash course.

In short: In our town, Lesa, we have to sort trash into six categories: “wet” (compost), plastic, glass, paper, metal, and “dry” (aka everything that isn’t recyclable, which isn’t much). Like our neighbors, we keep six bins in our kitchen, one for each category, and our kitchen is in fact designed around this need. (There’s yet a seventh “green” bin for yard waste, but that generally goes in the shed.) One type gets picked up every day except Sunday, meaning we have to put some form of trash out nearly every night. Some categories go in government-issued bags, while “wet” must be in biodegradable bags, glass goes in an unlined bin, and paper goes into designated reusable open bags.

It was a lot to learn. But once I got the hang of it, the recycling and trash sorting efforts stopped feeling like an inconvenience and became something like second nature. I’d go so far as to say it felt satisfying to contribute in this way on a daily basis.

Thirty years ago, Italian households mostly took out the trash in one go. Since then, nearly all residents of Italy have at some point reprogrammed their habits, just as I had to. This behavior shift, along with investment in domestic waste-processing infrastructure, has been integral to Italy’s recycling success.

The household bin arrangement: Most of the receptacles fit neatly into drawers and cabinets, with the exception of the paper bin. Sarah Stodola

Italy’s transformation into a recycling powerhouse began in 1997 with the Ronchi Decree, a law that created a compulsory minimum recycling rate of 35 percent, placed the responsibility for achieving it on municipalities, and empowered them to manage both the logistics and financing of the subsequent efforts. The law came about after a waste-management crisis in the region around Milan brought the issue of trash processing to the forefront of Italian politics. Most municipalities today set their own local waste collection tax rates (known as the TARI), while recently a few have moved to a “pay-as-you-throw system,” with fees based on the amount of waste a household generates.

The Ronchi Decree also placed responsibility for trash sorting at the household level — as opposed to a single-stream approach, where waste gets sorted at facilities — with measures to get residents on board built into the legislation. Marco Ricci, a circular economy expert in Italy who worked with the national government on the legislation’s rollout, points to several factors that helped shift individual behavior, including a new door-to-door collection system and, in most localities, giving residents the necessary bins and bags free of charge. Still, people needed convincing, with concerns about both costs and the program’s effect on their time and their kitchens.

“The resistance was approached in a very simple and effective way: a lot of local meetings,” Ricci said. He spent a few years going from town to town, working with mayors and other experts to explain the new scheme to residents. This federally coordinated outreach campaign ultimately reached about 50 percent of the Italian population, he said.

Regional implementation, rather than relying on a national system, was key. “It was fundamental,” Ricci said. “Italians are really closely linked to their community, and we made use of this community feeling.” Because small communities were easier to communicate with directly, rural areas ended up adopting the new system more quickly than the big cities. In addition, both local politicians and residents proved more willing to learn from others and hold neighbors accountable. As a result, a domino effect swept the less populated areas of Italy: Once people saw their neighbors using the new bins, they wanted their own, and once mayors saw neighboring towns finding success in recycling, they wanted in on it, too.

Fines for improper waste disposal were part of the equation, but equally important were softer incentives, such as the policy of providing residents a set allotment of bags for nonrecyclable trash, which is only picked up if it’s in those bags. If someone were to use up her allotment too quickly by including too many recyclable items, she’d be out of luck until the next allotment. This is all the motivation most residents need to sort their trash properly.

In 2006, additional legislation mandated raising Italy’s minimum recycling rate to 65 percent of all household waste, a requirement that went into effect in 2012 — years before the EU set the same standard in 2018. By then, Italy was well ahead of the game.

I met Maria Grazia Todesco while doing some volunteer translating for a local museum. She has lived in Italy her whole life and currently resides in Solcio, a town neighboring mine. Since she’s experienced Italian trash collection both before and after the changes of recent decades, I was curious to get her take. She told me that the new system definitely requires more effort and attention — but to her at least, it feels well worth it. “With a little goodwill, the task becomes easier,” she said. “I think it was a necessary choice and very useful if we want to somehow safeguard our planet. Each of us individuals can do a lot to achieve the goal.”

Lesa and Solcio are in the wealthier northern part of the country, where recycling efforts have long been among the best in Europe. In recent years, Italy’s southern regions have been making notable progress as well — despite the need for more processing facilities in the south and challenges with a wider recycling industry that resists close monitoring, similar standards and enforcement mechanisms now exist throughout the country.

Still, the need for reinforcement and education remains. Erum Naqvi, a friend of mine back in New York who also owns a home in Lesa, said she initially handled her trash the same as she would back in the States — which is to say, not thinking much about tossing most things into the bin destined for the landfill. But one afternoon, a local police officer showed up to give her a warning about sorting, bagging, and putting it out correctly. Naqvi quickly got herself up to speed. She is careful about sorting correctly and keeps the trash pickup schedule pinned next to her door, consulting it every day.

Naqvi has now changed her habits even back home. “Coming back to New York, I felt so guilty not doing it [to the same degree]. It’s instilled in me a more positive approach toward recycling,” she said.

For me, it’s been revelatory to witness the collective impact of individual efforts, and to participate in it. Nearly every evening in Lesa, households place the appropriate bags or bins out next to their doorsteps, creating a consistent tableau throughout town. Looking up the next morning’s category, then preparing it and putting it out, has become part of my after-dinner routine. Early every morning, collection trucks built small enough to pass through the town’s ancient, narrow streets arrive before most residents are awake — except on glass collection day. Those trucks arrive later so as to not wake residents with the inevitable clatter of glass as it’s dumped from the bins.

In the winter months, the nonrecyclable trash gets collected just once every two weeks. Nothing has surprised me more than finding myself struggling to fill even one small bag during that time, so thorough is my sorting of the recyclables. That’s a common observation — and a sign that individual action, like trying to produce less garbage, becomes a whole lot easier when the system is designed to support it.

— Sarah Stodola

Waste management has long been a troubled industry. When we as individuals “throw something away,” we’re really just sending it somewhere else for someone else to deal with — that same paradigm can play out on a global stage, even going so far as cross-border “waste trafficking.” One of this year’s prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize recipients, announced this week, helped challenge such a scheme between Italy and Tunisia. In 2020, Italy illegally sent 282 shipping containers filled with common household garbage to Tunisia. Thanks to prize winner Semia Gharbi, and other advocates, the majority of the waste was returned in February of 2022 to the same Italian port where it originated, as shown below — and the scandal also led to tightened regulations in the EU.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Italy got its citizens — and me — to adopt a rigorous recycling scheme on Apr 23, 2025.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Sarah Stodola.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Asia is mourning the passing of Pope Francis on Monday, who died aged 88 after a 12-year papacy. He had traveled extensively across Asia since becoming leader of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics in 2013.

During his visits, Francis drew large crowds in countries such as the Philippines, which is predominantly Catholic, but also Indonesia, Bangladesh and Thailand where Muslims and Buddhists were in the religious majority and Catholics were in the minority. He also visited South Korea, Japan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Timor-Leste and Singapore.

Here are moments captured during Pope Francis’s visits to Asia:

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Just Stop Oil and was authored by Just Stop Oil.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

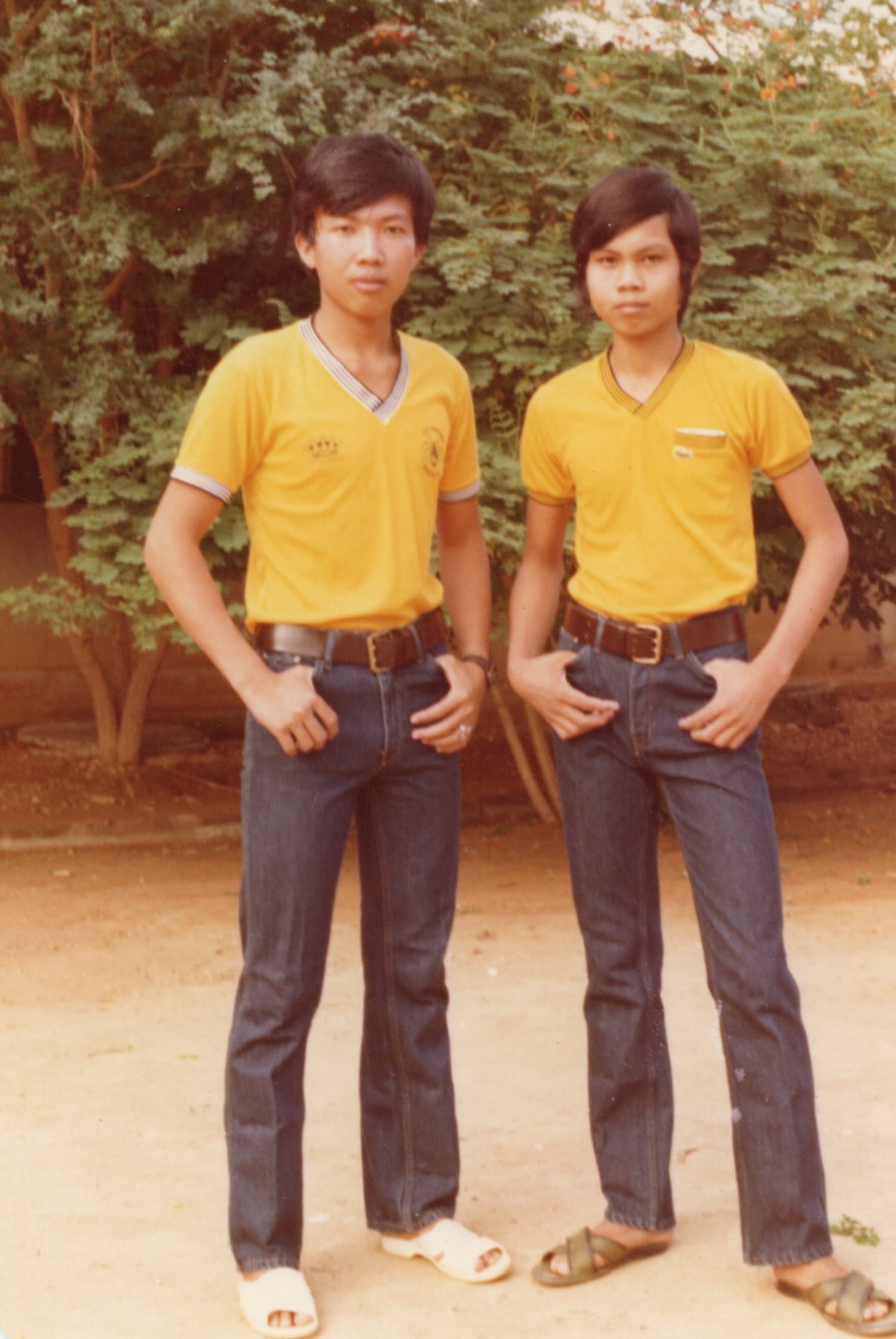

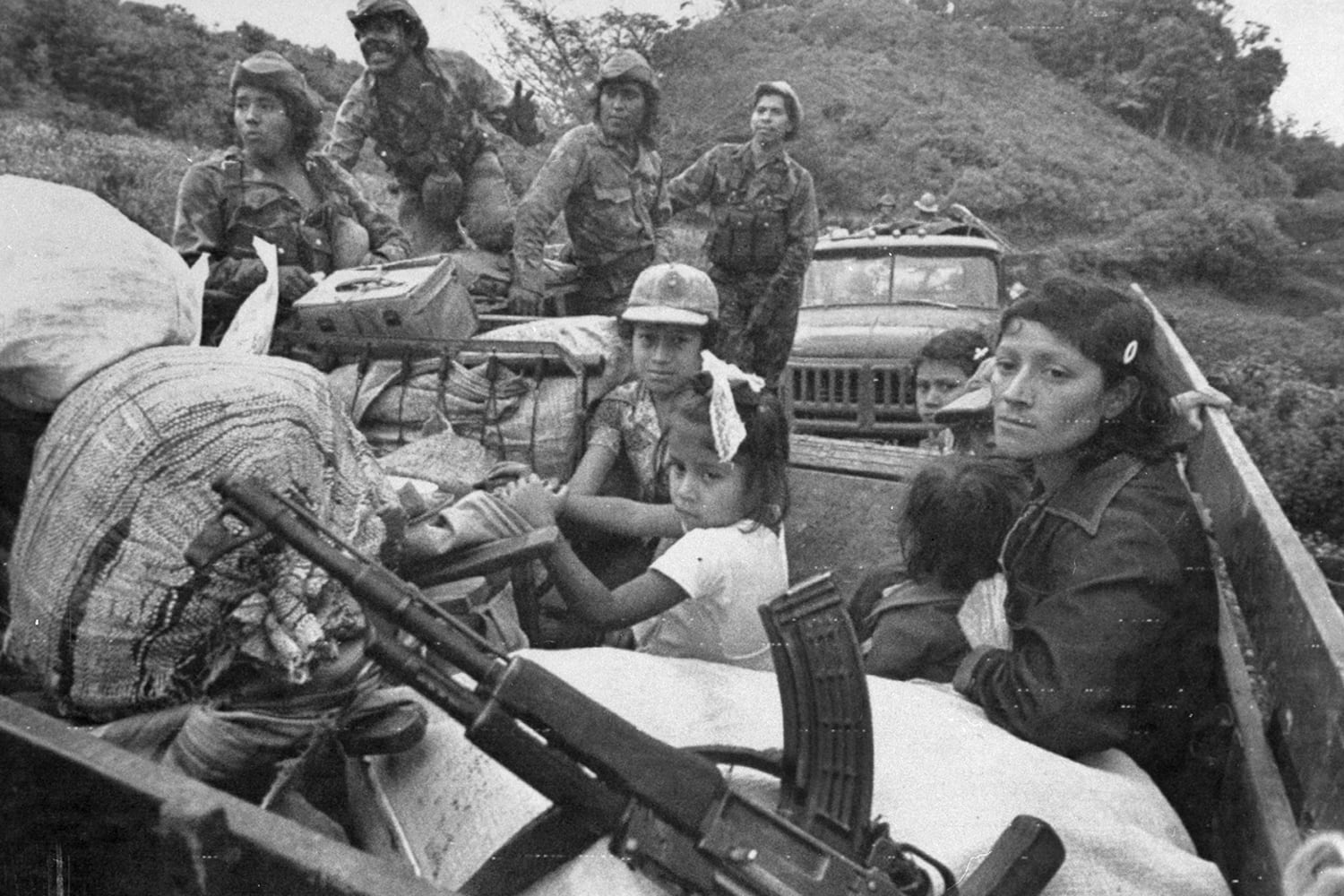

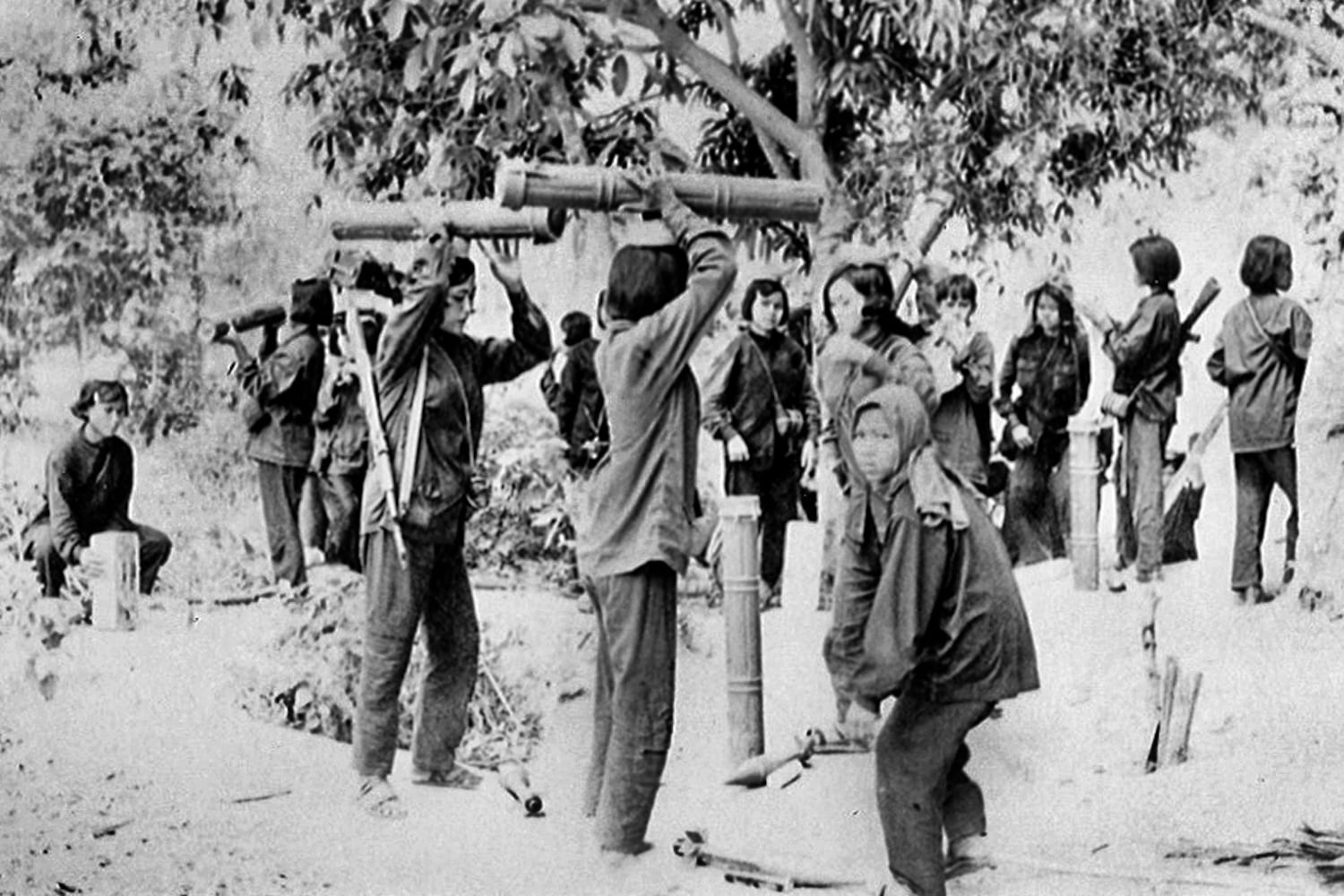

Part of a multimedia series on four RFA staff members who look back on life under the Khmer Rouge fifty years later

Poly Sam was 11-years-old when the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh on the same day as the traditional Khmer New Year holiday.

“It was meant to be a day of celebration, but it turned out to be a very, very bad day, and the beginning of a very bad time for many Cambodians,” he recalled recently.

April 17 marks the 50th anniversary of the Khmer Rouge’s victorious arrival in Cambodia’s capital. For Cambodians, it’s a day remembered for its horrific beginnings.

Within a handful of years, as many as 2 million people would be dead at the hands of the Pol Pot-led regime.

“You know, for me, there’s a lot of negative memories,” Poly said. “But it’s a memory that I can share with people because we don’t want anyone to go through this again.”

From Khmer Rouge survivor to a Thai refugee camp, and later as a teenage migrant to the United States, Poly encountered more than most people over five decades.

He witnessed unspeakable acts and extreme deprivation. And he survived when so many others did not.

“I’m lucky,” he said. “A lucky son of bitch.”

Before the Khmer Rouge, Poly’s brother, Sien Sam, was a school teacher who later became a soldier for Cambodia’s short-lived Lon Nol regime – the military dictatorship that was ousted in 1975.

Sien was one of the first to die as the Khmer Rouge forced everyone to walk out of Phnom Penh and into the countryside, Poly said.

Outside of the city, Khmer Rouge soldiers marched Sien away to be “re-educated.” Only later as the “disappeared” grew in number, never to return, did people begin to understand what was happening, according to Poly.

“He was probably killed in the first or second week. But we don’t know; nothing could be verified,” he said. “Until this day, we still don’t know where he died.”

Today, Poly lists why he is lucky: Lucky to have only lost four or five members of his family. Lucky to have never been tortured. And lucky to have endured.

“It’s very fortunate for a kid. You are in the field all the time, so you are able to scavenge a lot of things,” he said.

“You learn a lot of tricks on how to survive. For example, you catch the fish, you wrap the leaf around the fish, and you put it under the ground and you burn a fire on top. When nobody is around you pull it out and eat it.”

Surviving the Khmer Rouge was one thing, but escaping from Cambodia to Thailand was another.

He begged his mother to allow him to try to flee his country. She had lost her oldest son to the Khmer Rouge. Her two other sons were already living in the United States, and now she feared she was about to lose her last born.

Poly risked his life to flee the country, carefully making his way across Cambodia from one internally displaced person’s camp to another.

The last hurdle was the greatest: sneaking into a refugee camp on the Thai border that was tightly controlled by Thai soldiers authorized to shoot anyone on site.

The only way in was under the cover of darkness. Poly described his most dangerous moment and the lengths and depths of what it took to survive as a teenager.

The first hurdle was slipping under the barbed wire fences without being noticed by the Thai soldiers. Once inside the camp, the next challenge was to hide out of sight until United Nations workers took over control of the camp during daylight hours.

Poly hid in the one spot that no one would look: the communal pit latrine. He threw himself into it and waited for hours until it was safe to emerge.

After four years in the camp. Poly was brought to the United States in 1983. More than 100,000 Cambodians settled in the United States between 1979 and 1990. A total of more than 1 million fled Cambodia during the years of civil war and turmoil.

An American family informally adopted Poly, sent him to high school, and later helped him obtain a social worker degree at college.

He worked at that for seven years before joining Radio Free Asia’s Khmer service in 1997. He now leads the Khmer service as its director.

“Whatever happened in the past, nobody can undo it. We have to look to the future, so I will forgive,” he said.

“I have forgiven the Khmer Rouge. Some of them were victims themselves. So there’s no need to hold grudges against them.”

But he says it is a different story for former Khmer Rouge cadres who continue to hold and abuse power in Cambodia today: “It is very difficult to forgive them.”

Edited by Matt Reed

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Ginny Stein for RFA.

BANGKOK – Chinese President Xi Jinping ramped up rhetoric of unity in the face of protectionism and shocks to the global order as he continued his Southeast Asian tour on Thursday amid a tariff war with the United States.

China is in need of allies after the imposition of 145% tariffs on its exports to the U.S., Washington’s restrictions on its semiconductors and other trade barriers. President Donald Trump’s administration says it is retaliating due to China’s trade surplus, its shipments of synthetic opioids and restrictions on U.S. investment.

“China stood steadfastly with Cambodia in its just struggle against foreign invasion and for national sovereignty and independence,” Xi said in comments published by Cambodia newspapers including the English-language Khmer Times, ahead of his arrival from Malaysia.

“Together, the two countries have shared the rough times and the smooth and consistently supported each other in times of need,” Xi said.

The Southeast Asian country was bombed by the U.S. during the 1954-74 Vietnam War and invaded by Vietnam in 1978, forcing out the genocidal Pol Pot regime that came to power in the aftermath of the Cold War era conflict.

China is the biggest investor in Cambodia, constructing roads, airports and ports. It is also the biggest exporter to the kingdom.

The theme of unity in the face of unnamed adversaries has been a recurring theme in the Southeast Asian tour, which began on Monday in Vietnam before moving to Malaysia, where Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim hosted Xi at a welcome dinner on Wednesday.

“In the face of shocks to global order and economic globalization, China and Malaysia will stand with countries in the region to combat the undercurrents of geopolitical and camp-based confrontation, as well as the counter-currents of unilateralism and protectionism,” Xi said, without naming the camp it saw as its biggest threat.

Xi discussed green technology, artificial intelligence and a US$11.2 billion railway project during a meeting with the Malaysian king, Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar on Wednesday, Chinese state news agency Xinhua reported.

China is the biggest exporter to Malaysia and the country’s biggest investor. The same is true of Vietnam, where Xi signed 45 agreements on areas such as improved supply chains and a railway project.

China had been working on a decoupling strategy long before Donald Trump took up his second term as U.S. president this year. By 2023, nearly two thirds of its economic growth was driven by domestic consumption, World Bank data show.

“At the same time, China has pursued deeper economic integration with the rest of the world,” according to Lili Yang Ing, secretary general of the International Economic Association.

“The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, now the world’s largest trade bloc, exemplifies China’s pivot toward Asia,” she said.

“Beijing has also strengthened Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements with ASEAN, South Korea, and several Middle Eastern economies, while negotiating new agreements in Africa and Latin America,” Ing said.

“These diversified trade and investment channels buffer China from U.S. pressure.”

Southeast Asian nations could also help in the face of America’s call on them to cut their trade surpluses and stop re-exporting Chinese goods as their own.

While Trump declared a three-month cut to 10% on “retaliatory tariffs” against Southeast Asian nations, they face a return to some of the highest U.S. tariffs in the world if trade talks are unsuccessful after those 90 days are up: 24% for Malaysia, 46% for Vietnam and 49% on Cambodian exports.

Edited by Taejun Kang and Stephen Wright.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Mike Firn for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

BANGKOK – Chinese President Xi Jinping ramped up rhetoric of unity in the face of protectionism and shocks to the global order as he continued his Southeast Asian tour on Thursday amid a tariff war with the United States.

China is in need of allies after the imposition of 145% tariffs on its exports to the U.S., Washington’s restrictions on its semiconductors and other trade barriers. President Donald Trump’s administration says it is retaliating due to China’s trade surplus, its shipments of synthetic opioids and restrictions on U.S. investment.

“China stood steadfastly with Cambodia in its just struggle against foreign invasion and for national sovereignty and independence,” Xi said in comments published by Cambodia newspapers including the English-language Khmer Times, ahead of his arrival from Malaysia.

“Together, the two countries have shared the rough times and the smooth and consistently supported each other in times of need,” Xi said.

The Southeast Asian country was bombed by the U.S. during the 1954-74 Vietnam War and invaded by Vietnam in 1978, forcing out the genocidal Pol Pot regime that came to power in the aftermath of the Cold War era conflict.

China is the biggest investor in Cambodia, constructing roads, airports and ports. It is also the biggest exporter to the kingdom.

The theme of unity in the face of unnamed adversaries has been a recurring theme in the Southeast Asian tour, which began on Monday in Vietnam before moving to Malaysia, where Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim hosted Xi at a welcome dinner on Wednesday.

“In the face of shocks to global order and economic globalization, China and Malaysia will stand with countries in the region to combat the undercurrents of geopolitical and camp-based confrontation, as well as the counter-currents of unilateralism and protectionism,” Xi said, without naming the camp it saw as its biggest threat.

Xi discussed green technology, artificial intelligence and a US$11.2 billion railway project during a meeting with the Malaysian king, Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar on Wednesday, Chinese state news agency Xinhua reported.

China is the biggest exporter to Malaysia and the country’s biggest investor. The same is true of Vietnam, where Xi signed 45 agreements on areas such as improved supply chains and a railway project.

China had been working on a decoupling strategy long before Donald Trump took up his second term as U.S. president this year. By 2023, nearly two thirds of its economic growth was driven by domestic consumption, World Bank data show.

“At the same time, China has pursued deeper economic integration with the rest of the world,” according to Lili Yang Ing, secretary general of the International Economic Association.

“The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, now the world’s largest trade bloc, exemplifies China’s pivot toward Asia,” she said.

“Beijing has also strengthened Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements with ASEAN, South Korea, and several Middle Eastern economies, while negotiating new agreements in Africa and Latin America,” Ing said.

“These diversified trade and investment channels buffer China from U.S. pressure.”

Southeast Asian nations could also help in the face of America’s call on them to cut their trade surpluses and stop re-exporting Chinese goods as their own.

While Trump declared a three-month cut to 10% on “retaliatory tariffs” against Southeast Asian nations, they face a return to some of the highest U.S. tariffs in the world if trade talks are unsuccessful after those 90 days are up: 24% for Malaysia, 46% for Vietnam and 49% on Cambodian exports.

Edited by Taejun Kang and Stephen Wright.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Mike Firn for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Image by Levi Meir Clancy.

The world is witnessing an unconscionable silence as Israel, an occupying power, imposes a total food blockade on Gaza—an act of collective punishment against a captive civilian population. As famine tightens its grip and American-made bombs rain from the sky, global leaders stand by—paralyzed, indifferent, or willfully complicit—while Israel renders Gaza uninhabitable.

Earlier this week, Israel targeted the only functioning medical facility serving over a million people in northern Gaza. Al Ahli Baptist Hospital was given just 20 minutes—in the dead of night—to evacuate hundreds of patients and wounded civilians. This second attack on the medical facility was enabled by then-U.S. President Joe Biden’s exoneration of Israel for its earlier massacre targeting the same hospital in October 2023—an assault that killed over 500 civilians sheltering outside its grounds.

But this was not an isolated attack. Hospitals, medical facilities, ambulances, and first responders have been systematically and relentlessly targeted in Gaza as in no other war in modern memory. Doctors have been kidnapped or killed while performing surgeries. Ambulances bombed mid-rescue. Entire medical complexes reduced to rubble while filled with patients, newborns, and the wounded. This is not collateral damage—it is a campaign of annihilation against the very institutions meant to save lives. In Gaza, saving lives has become a death sentence.

The United Nations, constrained by the U.S. veto power, has failed to pass a resolution demanding an end to what many increasingly recognize as genocide. Meanwhile, the United States—self-styled as a beacon of human rights—actively abets these atrocities. It supplies Israel with massive bombs, including 2,000-pound munitions, enabling their use in densely populated areas. This is not merely a moral failing; it is a flagrant violation of both U.S. and international laws governing military aid.

Much of this impunity stems from the legacy of Donald Trump emboldened Israel through a series of reckless, one-sided decisions: recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, slashing humanitarian aid to Palestinians, and endorsing illegal Jewish-only colonies on stolen Palestinian land. Trump gave Israel carte blanche to act without fear of accountability. His abject support signaled that no matter how flagrant the violations, there would be no consequences—only more weapons, more diplomatic protection, and deeper impunity.

Today, Israel carries out its campaign of destruction while invoking Trump’s so-called “vision” for Gaza—an evil blueprint of ethnic cleansing. This vision has become a license of an Israeli roadmap for dispossession, displacement, and death.

This has indulged Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s relentless appetite for Palestinian land—prolong the suffering of Israeli captives, Palestinian prisoners, and the people of Gaza. His refusal to pursue a meaningful ceasefire or prisoner exchange is a calculated political maneuver. The ongoing war serves his far-right racist coalition, distracts from his legal troubles, and consolidates his grip on power while advancing an expansionist agenda. In the process, Gaza has become what can only be described as a starvation death camp—where civilians are punished collectively, denied food, water, medicine, and even hope.

Meanwhile, in the occupied West Bank, Israeli military raids and settler mobs have escalated dramatically. Entire communities are being uprooted and terrorized with impunity. Yet, the Palestinian Authority (PA)—the supposed protector of Palestinians—has shown paralyzing impotence. Rather than confronting Israeli aggression or protecting its people, the PA functions as a subcontractor for the occupation, policing its own population while Israeli forces and armed settlers freely brutalize civilians. Its failure to act has not only eroded its legitimacy but made it complicit in the very oppression it claims to oppose.

And still, the international community looks away.

But perhaps the most disgraceful silence comes not from Washington or Brussels—but from Arab capitals. This is not mere neglect or indifference. It is betrayal—a betrayal rooted in cowardice, authoritarianism, and self-preservation at the expense of justice.

The regimes in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and others have become accessories to genocide and complicit in the siege on Gaza. Their silence, their closed borders, their collaboration and normalization with Israel—all point to a level of complicity that history will neither forget nor forgive. As Gaza’s children starve and entire families are buried beneath rubble, Arab leaders ingurgitate in palaces, and issue timid statements devoid of conviction, or consequence.

It is a painful irony that while protests erupt in cities like London, Paris, and New York, there is near-total silence in Cairo, Riyadh, Amman, and Abu Dhabi. The moral clarity of Western citizens who take to the streets in solidarity with the Palestinians underscores the betrayal of those who claim religious, linguistic, and cultural kinship with them. But the failure is not only at the top. Public apathy, and resignation in many Arab and Muslim societies have enabled this silence—allowing Israel to persist in its crimes. A people conditioned to accept humiliation cannot demand justice.

The evil of occupation and military aggression is sustained not only through bombs and blockades but through the slow erosion of courage and moral standards. Atrocities once shocking now pass as routine. The world becomes numb. The killing of children, the destruction of homes, and the denial of basic necessities no longer elicit outrage. The question becomes not how such acts are tolerated, but when genocide becomes mere statistics—counting whether more or fewer people were killed today compared to yesterday.

This normalization turns ordinary people into complicit actors—bureaucrats who process arms shipments, journalists who frame one-sided narratives, citizens who choose silence over dissent. All become part of a system that sustains injustice.

A genocide is unfolding in real time, and the silence is not just deafening—it is damning. It is time for the people in Arab and Muslim capitals to at least join the protestors in Western cities and break this silence. To speak with moral clarity. To meet the demands of the moment. And to reject the normalization of evil in Gaza.

The post The Deafening Silence: Arab Complicity and the Normalization of Evil in Gaza appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Jamal Kanj.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This story originally appeared in Common Dreams on Apr. 14, 2024. It is shared here with permission under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license.

“Everyone here is pretending,” said immigration policy expert Aaron Reichlin-Melnick as a video of Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele speaking in the Oval Office circulated on Monday.

Bukele, said the senior fellow at the American Immigration Council, was pretending “that he’s incapable of releasing” Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Maryland resident whom the Trump administration expelled to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT) in March, while President Donald Trump continued to pretend he’s unable to demand Abrego Garcia’s release.

When reporters asked Bukele to weigh in on Abrego Garcia’s case, the Salvadoran leader scoffed.

“Of course you’re not suggesting that I smuggle a terrorist into the United States,” he said. “How can I return him to the United States, do I smuggle him into the United States? …I don’t have the power to return him to the United States.”

Abrego Garcia entered the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant in 2011. He was accused by a police informant of being a member of MS-13 in 2019, but he denied the allegations and was never charged with a crime. He was denied asylum in a hearing, but a judge determined that he should not be deported to his home country of El Salvador, where he had a credible fear of facing persecution and torture.

He had been working as a sheet metal worker and living in Maryland with his wife and children for several years when he was among hundreds of people accused of being criminals and rounded up to be expelled to El Salvador under a Trump administration deal with Bukele last month.

In the Oval Office on Monday, Bukele joined the Trump administration in claiming nothing can be done to return Abrego Garcia to his family in Maryland.

“The U.S. is pretending it doesn’t have the power,” said civil rights lawyer Patrick Jaicomo. “And Bukele is pretending he doesn’t have the power. So who has the power?”

The Supreme Court last week said the administration is responsible for “facilitating” Abrego Garcia’s release, and the Department of Justice claimed in a filing on Sunday that under that order, it is only liable for allowing the man to enter the U.S. once he is freed from the prison in El Salvador.

Trump’s treatment of the case represents “a full-blown constitutional crisis and possibly the watershed moment for what the near future looks like,” said one writer. “If this holds, there is no law but Trump’s law.”

In the Oval Office, said J.P. Hill, both leaders were “openly saying they’ll defy the Supreme Court and maybe even send American citizens to the prison camp in El Salvador. Nobody will be safe if we let this happen.”

As Bukele and Trump both denied responsibility for the hundreds of people they have sent to CECOT, Documented reported on Merwil Gutiérrez, a 19-year-old Venezuelan immigrant who was also sent to El Salvador.

Gutiérrez has no criminal record in the U.S. or his home country, and was not a target of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s deportation operation. An ICE agent said, “He’s not the one,” when a group of officers came to make an arrest at Gutiérrez’s apartment building, but another replied, “Take him anyway.”

Gutiérrez’s story, said Reichlin-Melnick, “comes as Bukele today pretends that he has no power to release people held in his own prison.”

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by Julia Conley.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Part of a multimedia series on four RFA staff members who look back on life under the Khmer Rouge fifty years later

The parents waved goodbye to their tearful 13-year-old son. The father patted the boy on the shoulder, reassuring him that he would return soon.

There was no hiding that the parents of Vuthy Huot were overjoyed to be returning to Phnom Penh. It had been six weeks since the family was forced out of their home and marched out of the city.

A mass trauma event. Two million inhabitants evacuated overnight, creating a ghost city in their wake.

Now, the son was being asked to stay behind in a rural village, and for the first time in his life, Vuthy was being separated from his parents. He was told he was the only one his father could trust to care for his elderly grandmother.

“I was very upset. That was the first time I was separated from the family,” Vuthy said recently from his office at Radio Free Asia’s Washington headquarters. “But my father tapped me on my shoulder and said, ‘Stay strong, we will come back and get you as soon as we settle down in Phnom Penh.‘”

The past weeks had first offered excitement for a young city boy who thought he was about to have the chance to go to the countryside with his family.

“I was very happy that I would spend time with my family and would see the countryside. But soon all the happiness and joy disappeared,” he said.

During the walk out of Phnom Penh, Vuthy watched helplessly as both his father and brother-in-law were separated from their family group. Khmer Rouge cadre, who had first been friendly, then angry, took the two men aside, tied their hands with rope, then strung them together and marched them away from the family.

“They walked at almost the same time along the road with us, so I could see them probably for the first few days,” he said.

Vuthy believes adult men were separated from their families to facilitate the evacuation.

Vuthy and his other family members made it to the village in Prey Kabas commune, Takeo province – about 90 km (56 miles) from the capital. His father and brother-in-law would arrive in the village shortly afterward.

In the days to come, Khmer Rouge cadre began vetting the “new people,” the disparaging name given to evacuees from the city.

Vuthy said his father told the truth: He was a skilled cartographer. Surprisingly, his reply was welcomed.

“The Khmer Rouge people stood up and said ‘We need your skill. We want you to come back and work for Angka.‘”

As quickly as they had arrived in the village, his father, mother and three of his brothers were turned around to return to Phnom Penh.

Days later, his sister was also taken away. Both she and her husband were sent to work in the fields.

Still in the village, Vuthy’s immediate mission was to learn how to keep himself and his grandmother alive.

“I didn’t know how to catch a fish, frog, crab or snake,” he said. “And as a newcomer, nobody wanted to talk to us, because they considered us traitors.”

He also didn’t know how to cook, and his grandmother, a staunch Buddhist, refused to kill anything that was alive. When he did manage to catch fish and crabs and brought them to the kitchen, she wouldn’t touch them.

It was only a matter of weeks after his parents left that his grandmother died of starvation. He was now alone. He vowed he would live to be reunited with his parents.

The first year under the Khmer Rouge was the most difficult. Vuthy was sent to work in the rice fields. There was a massive flood in the first wet season, and food was scarce.

He was settled alongside a river in northwestern Cambodia where he lived on an elevated bamboo platform. Scores of other platforms were nearby, divided into family groups. As the rain fell, the river rose until the platforms were surrounded by water.

He remembers the leeches and the kindness of a woman he called Aunty Poh, who slept on the platform next to him with her three children. She cut up her skirt to make pants for him to protect him from the leeches.

“The Khmer Rouge people would come in the evening by boat and would distribute one bowl of rice per family,” he said. “If you had three people in a family, you would have three spoonfuls of rice. I was by myself, and I only had one spoon.”

That first wet season, the river remained high for two months. When he finally took off those pants to wash them, they were covered in the trails of hundreds of leeches. He had survived.

Aunty Poh, who made the pants for him, did not. Neither did her children. She kept the body of her last child next to her for days, to claim his meager rice allocation until she could no longer. Hunger killed both of them. Vuthy came close to succumbing.

“You know when people die of hunger, they usually die at around 3 or 4 in the morning,” he said.

That last rasping gasp is a sound he remembers himself making. It woke his neighbor, Aunty Poh. She opened his mouth with a spoon and fed him the rice porridge he had saved for the morning.

“When your body feels this porridge, you start to have feeling, you feel the food and you can move. I was still conscious, but I could not move.”

For Vuthy, many memories remain painful, but worse, there are others he can no longer summon.

“I don’t remember the faces of my parents or my brother or sister. I don’t have any photos left of any of them. The Khmer Rouge destroyed or burnt all photo albums.”

What made him survive when so many others did not, he attributes to one of the greatest human emotions – that of hope.

“If you have hope, you have the inspiration to stay alive, to fight and stay alive.”

For four years, Vuthy held on, believing he would one day be reunited with his parents. When the Khmer Rouge were ousted from power in 1979, he walked back to the capital. Each day for more than three months, he would wait at the city gates, wanting them to walk into view.

Eyewitnesses who knew his parents told him what happened. They died not long after they left him behind in the village, and just before they reached Phnom Penh.

The boat transporting them by river to the capital had capsized in front of the Royal Palace. Overladen with people happy to be returning to the city, there had been a rush to one side of the boat. It lurched to one side and sank.

From that day to this, one thing has kept him going. A mantra that he tells himself often. It begins with “at least.”

“At least I survived. At least I survived and continued to represent my family. At least my family, my mother, my father, my sister and my brothers do not have to go through all the hardship that I did during the Khmer Rouge. At least, while they died horribly, by drowning, but at least they no longer suffered.”

In recent years, as an on-air host and deputy director of RFA’s Khmer service, Vuthy has watched as Cambodia has slid from a democracy to authoritarianism. That has been difficult to witness, he said.

“Go back to the history of Cambodia itself. It has gone through a lot,” he said.

”But if we don’t keep fighting. We won’t survive. We have only one life to live, and we all die sooner or later. Do something good. Do something for your country.”

Edited by Matt Reed

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Ginny Stein for RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.