This content originally appeared on Amnesty International and was authored by Amnesty International.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Amnesty International and was authored by Amnesty International.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A video of a seemingly distressed woman crawling out of a bush in wet clothes is viral on social media. Users are sharing this footage with the claim that she is a Hindu woman, who was raped and tortured in Bangladesh.

In the video, the crowd surrounding the woman shines a torchlight on her and calls for her to come out while others assure her that she won’t be beaten up. Those sharing the video allege that the no one helped the tormented woman who was being made fun of by “extremists”. The incident is purportedly from Narayanganj in Bangladesh.

The neighbouring country has been in the eye of flaring communal tensions for some time now.

The above video was shared by Faraz Pervaiz (@FarazPervaiz3) on X (formerly Twitter) on December 27, 2024 with a caption saying that a Hindu woman was brutally raped in Araihazar village in Narayanganj while Muslims made fun of her.

The post garnered around 44,000 views.

The claim was further amplified by X account Rinti Chatterjee Pandey (@mainRiniti), who shared Asifur Rahaman Chowdhury’s post the following day. The translated text reads, “A Bangladeshi Hindu woman is raped by several people and then a video is being made. Not even a single person came to save her, and our government is sending rice to feed Bangladeshi dogs. This is too much.”

एक बांग्लादेशी हिंदू महिला के साथ कई लोग बलात्कार करते हैं और फिर उसका वीडियो बनाया जा रहा है । बचाने एक आदमी तक नहीं आया , और हमारी सरकार बांग्लादेशी कुत्तों का पेट भरने के लिए चावल भेज रही है हद है pic.twitter.com/QIOLB68WRN

— Riniti Chatterjee Pandey (@mainRiniti) December 28, 2024

The post garnered around 1.5 million views.

Another X user, Asifur Rahman Chowdhury (@Asifurrahman71), also shared the video with a similar claim and the hashtag #SaveBangladeshiHindu. His post had around 206,000 views.

Several others also shared similar claims. You can see them in the gallery below.

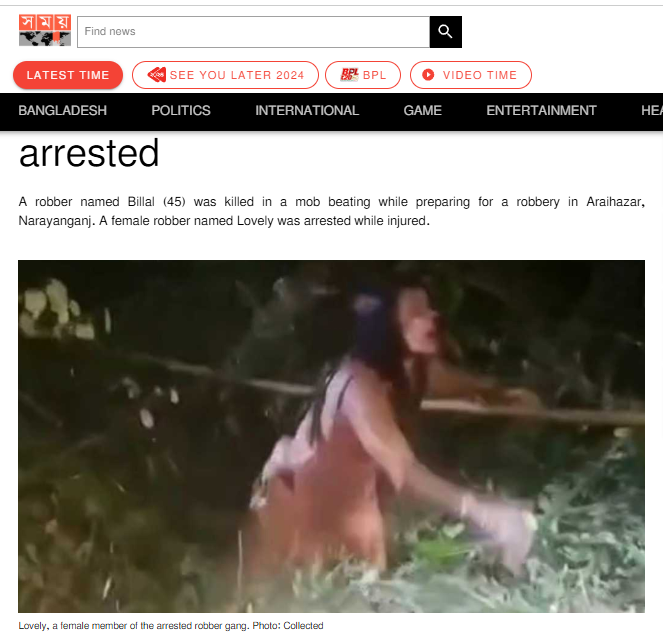

Click to view slideshow.A keyword search led us to a news article by Bangladeshi media outlet Somoy News. The report, published on December 27, 2024, features an image similar to the visuals in the viral video. According to this report, the previous day, a group of seven or eight people were trying to steal a car from Ilumdi road in Kahindi village, Araihazar, Narayanganj. However, the residents soon realised what was happening and began chasing the robbers, who then tried to escape. However, one of the robbers, Billal, was caught by the mob and lynched to death. The mob also spotted an alleged associate of Billal, a woman named Lovely. In a bid to save herself, this woman reportedly jumped into a canal. The report identifies her in an image, making it clear that it is the same woman seen in the viral video.

INSERT SIMILARITY EDIT

The villagers rescued her and handed her over to the police. She was then sent to the Araihazar Upazila Health Complex.

Confirming the incident, assistant superintendent of Araihazar police, Mehedi Islam, told Somoy News that the deceased robber, Billal, was a known criminal with at least nine pending cases. He had been named in murder and robbery cases in the past. He said that the woman, Lovely, had been arrested and they were preparing to file a case against her, adding that the 25-year-old woman was also beaten up by the mob.

Dhaka-based news outlet Prathom Alo reported that during initial investigation, Lovely admitted to being associated with the gang of robbers that escaped but later denied any involvement. She claimed that she was a sex worker and with a client in the area at the time of the incident. Reportedly, scared after people began screaming, she tried to run away but was caught and beaten up by people, who suspected she was with the gang of robbers. She then jumped into the canal to escape, the report said.

During our investigation, we found a video uploaded on the Facebook page of local news portal, Araihazar Times, on December 27, 2024. The caption refers to the woman as Lovely Begum. In this, she can be heard saying that she was attacked by robbers while travelling in an auto-rickshaw. They took her hostage while the auto driver fled and informed local residents. This led to the now-deceased robber getting lynched and Lovely was also beaten as a suspect.

,

গতরাতে ডাকাত সন্দেহে গনপিটুনীর শীকার লাভলী বেগম ঘটনার ব্যাখ্যা দিলেন যেভাবে ?

ভিডিও ধারণ: কাউসার আহাম্মেদ।

Posted by আড়াইহাজার টাইমস on Friday 27 December 2024

Alt news spoke to a Bangladeshi journalist who confirmed that the woman seen in this video was named Lovely and she was not a Hindu. Neither was she raped. She jumped into a canal to save herself from the being beaten up by the angry villagers, who presumed she was involved in a robbery.

Thus the viral video has been falsely given a communal angle. The woman in the clip is not a Hindu. Her name is Lovely Begum and she belongs to the Muslim community. She jumped into a canal to save herself from being beaten up by the villagers, who believed she was involved in a robbery.

The post No, this video does not show Hindu woman raped and tortured in Bangladesh village appeared first on Alt News.

This content originally appeared on Alt News and was authored by Ankita Mahalanobish.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Plans to proceed with a benefits-and-risks review of a proposed hydropower dam on the Mekong River has sparked concern in both Laos and Thailand about the impact on communities and the ecosystem.

The US$2-billion, 12-turbine Sanakham hydropower dam will be built about 155 kilometers (100 miles) west of the Lao capital of Vientiane, and 25 km (15 miles) upstream from Sanakham district of Vientiane province, near the Thai-Lao border.

More than 62,500 people in Thailand and Laos will be forced to relocate due to rising waters, according to submitted documents.

Lao residents say they have hardly had a chance to give feedback on the project.

“I’m so concerned that we’ll have to move to another village,” a Sanakham district resident told Radio Free Asia. “They [the government] did not clearly explain it to us at all.”

Dozens of hydropower dams have already been built on the Mekong and its tributaries, and there are plans to build scores more in the coming years. The Lao government wants to harness their power generation to boost the economy, which has been battered by soaring inflation and a weakening currency.

Electricity generated by the dam, to be built by China-owned Datang (Lao) Sanakham Hydropower Co. Ltd. and Thailand’s Gulf Energy Development Public Co. Ltd., will mainly be exported to Thailand.

Thailand’s Office of National Water Resources said on Dec. 17 that it would begin the consultation process during which Mekong River Commission member countries and other stakeholders review proposed projects to try to reach a consensus on whether or not they should proceed.

The Thai National Mekong Commission is holding four public information forums about the dam for residents living in the eight Thai provinces along the Mekong River during the coming weeks.

‘Rushed ahead’

International Rivers, a group acting to protect rivers and the communities that depend on them, said there there has been little up-to-date information publicly available about the project.

“It appears this process is being rushed ahead, with little regard for the needs of local residents to be able to make arrangements to attend the forums, let alone prepare and develop informed opinions about the project specifics,” the group said in a Dec. 21 statement.

Villagers who will be affected by the dam don’t want to move, a resident of Kenethao district in Xayaburi province said.

“They don’t want to relocate at all [because] here they have their livelihoods,” he said. “If they moved somewhere far away, what would happen to their lives? If they have no choice but to move, then they should get more compensation.”

Phonepaseuth Phouliphanh, secretary general of the Lao National Mekong Committee, told Radio Free Asia that the project developer will take into consideration concerns raised about the dam.

RELATED STORIES

Planned Lao dam raises concerns in Thailand over impacts on shared border

Laos pushes ahead with large dam projects, despite uncertainty of power purchases

Thai NGOs urge government not to buy power from Sanakham Dam in Laos

“All project developments have both good and bad impacts which we cannot avoid,” he told Radio Free Asia. “We have done research to ensure the impact is as little as possible.”

After hearing the concerns from people in areas to be affected by the dam, the Lao government or the project developer will review and correct issues that may occur, he added.

Thai concerns

Meanwhile, some Thai residents and advocacy groups also oppose the construction of the dam.

Channarong Wongla, a member of the Chiang Khan Conservation Group and Local Fisheries Group in Chiang Khan, a district in Thailand that will be affected by the dam, said other hydropower projects have already altered water routes and islands and caused erosion.

With hydropower projects in the past, including Laos’ Xayaburi Dam, developers moved ahead with their projects regardless of the concerns raised by residents, he told International Rivers.

“Most importantly, for the Sanakham Dam project, the [Thai] ombudsman and the National Human Rights Commission have already provided a clear basis for a more precautionary approach recognizing the serious impacts on local people and ecosystems,” he was quoted as saying.

A report by the ombudsman said there “was still a serious lack of information on the transboundary impacts of the dam project and that clear commitments of accountability are required from both the developers and government agencies in Thailand,” he said.

Construction of the Sanakham Dam was expected to begin in 2020, but was put on hold when government officials from Thailand’s National Mekong Commission raised questions about the impacts of the project and called for comprehensive technical studies on its environmental, social and transboundary effects, according to International Rivers.

The “snap decision” to schedule expedited public information sessions for the Sanakham Dam marked a distinct shift in the Thai government’s approach to the project, the group said.

Translated by RFA Lao. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Lao.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

TAIPEI, Taiwan – Chinese state media has launched a campaign to highlight friendly cooperation with the United States in an attempt to improve turbulent ties as a new administration under Donald Trump prepares to take office, an analyst said.

The state-run People’s Daily and Global Times, which often carry searing criticism of the U.S., called on Dec. 25 for written work, photos and videos from people and organizations around the world with the aim of “bridging cultural differences and fostering friendship and trust” with the U.S.

“What they are doing now is part of the latest efforts by the Chinese government to foster a more collaborative relationship with the Trump administration,” Li Wei-Ping, a researcher with Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, told Radio Free Asia.

President-elect Donald Trump has made no secret of his plans to hit China with massive tariffs and experts say his second presidency looks set to become dominated by a grand rebalancing of trade ties.

Li said that China has been working to steer its relations with the U.S. in a more positive direction since Trump’s election win, with remarks by top officials such as Foreign Minister Wang Yi and the tone of state media editorials.

Wang, in a Dec. 27 commentary in the state-run Study Times, urged the new U.S. administration to “make the right choices” by working with China and “striving for stable, healthy, and sustainable development in Sino-U.S. relations.”

Xinhua News Agency, in a Dec. 28 editorial, also extolled people-to-people exchanges such as tourism in fostering relations.

“The talk, the articles, and the campaign … could be deemed as a whole as an indication that the Chinese government is preparing for the Trump administration 2.0.,” said Li.

RELATED STORIES

Trump ‘invited’ China’s Xi to inauguration in Washington

More China trade ‘hawks’ among Trump’s top State Department picks

US targets China’s chip industry with new export controls

Trump had also made friendly gestures to China such as his invitation to Chinese leader Xi Jinping to his inauguration in January, said Li, while noting that many factors could impact what had been a “turbulent” relationship in recent years.

Trump has, for instance, nominated outspoken China critics to top jobs: Marco Rubio for secretary of state; Rep. Mike Waltz of Florida for national security adviser, and Rep. Elise Stefanik of New York as ambassador to the United Nations.

Trump then announced on Dec. 9 he had picked three China trade hawks for top roles at the State Department, including Michael Anton, who has previously argued it is not in U.S. interests to defend Taiwan from an invasion by China.

In early December, the Chinese Foreign Ministry called on the U.S. not to do anything to undermine Beijing’s territorial claim on Taiwan, enshrined in its “one-China” principle.

“I am hesitant to say the narrative has totally shifted and believe we need more time to see if this current amicability will last,” Li said.

Editing by Taejun Kang.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Alan Lu.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In a three-part series, Radio Free Asia examines the reach of the Chinese Communist Party far beyond its borders, on U.S. college campuses and through technology.

RFA speaks with victims of intimidation, policy experts, and lawmakers on what’s at stake.

Episode 1 delves into incidents like a Harvard University protester being forcibly removed by a Chinese Communist Party-linked student, a violent attack at a Columbia University vigil and the harassment of Georgetown students for advocating democratic values.

The documentary uncovers how these students and their families face surveillance, intimidation, and retaliation, both abroad and in China, raising urgent calls for stronger protections and accountability to safeguard freedom on American campuses.

Episode 2 investigates the potential national security risks posed by TikTok and its parent company, ByteDance, amidst allegations of connections to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Explained are the platform’s data collection practices, its potential to manipulate users through algorithms, and the broader implications for American privacy and democracy.

As the deadline for ByteDance’s divestment of TikTok is approaching, the episode raises critical questions about balancing national security with the principles of an open society.

Episode 3 reveals a recent cyberattack uncovered by Proofpoint, a leading American cybersecurity firm specializing in email security and threat defense.

Proofpoint identified a China-linked hacker group, “UNK_SweetSpecter,” targeting technical personnel connected to a top AI company.

Using phishing emails with malware, the group sought to steal intellectual property, coinciding with U.S. export restrictions on AI models. Despite improved international intellectual property laws, enforcement remains inconsistent.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read about tsunami preparedness 20 years later at BenarNews

Faced with the daunting task of reclaiming neighborhoods, beachfront properties and areas around mosques, repairs began quickly in sections of Indonesia and Thailand devastated by the deadly Dec. 26, 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

A 9.1 magnitude earthquake struck in waters off Sumatra, generating a giant tsunami where waves topped over 160 feet (48.7 meters) in Indonesia’s Aceh province.

After the waters finally calmed down, the death toll globally climbed to about 230,000, including about 167,000 in Aceh, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which estimated damage at U.S. $13 billion.

Within a few years, life returned to a semblance of normal because of efforts to reclaim and rebuild what was lost in the two countries hit hard by the wall of water. In many places, few signs of the destruction are visible in 2024.

Those efforts are captured in a series of before-and-after photos:

See a version of this gallery on BenarNews — an RFA-affiliated online news organization.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by BenarNews staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A monsoon storm brewed above Boonrat Chaikeaw as he cast his net into the endless tide of trash in the Mekong River on one day in June. He brought home more plastic than fish over six trips into the polluted waters of the Golden Triangle between Thailand, Myanmar and Laos.

Below the Golden Triangle, at the center of the river’s lower basin, children swam among plastic debris as workers cleared the riverbanks of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh — with identical plastic pick-up efforts on Tonle Sap lake.

Further downstream, in Vietnam, the river spiderwebs into the tributaries, swamps and islands that comprise the Mekong Delta. In Can Tho, which lies along a Mekong tributary, fish farmers are relieved to no longer be living off a river besieged by plastic waste.

The Mekong River supports millions of people along its 4,300-kilometer (2,700-mile) path from its headwaters in the Tibetan Plateau through Southeast Asia and eventually into the South China Sea.

But its size and the politics of shared management has made it particularly susceptible to plastics pollution.

Globally, the Mekong river is among the waterways most responsible for such waste reaching the world’s oceans. The waste isn’t simply unsightly. Plastic pollution threatens thousands of species that rely on a free-flowing river while human consumption of microplastics poses a growing health concern.

Many hoped that a United Nations-led Global Plastic Treaty would ease the plastic pressures on rivers, but disagreements over plastic production and chemical use left the supposed landmark treaty unsigned earlier this month.

Negotiators now look to the sixth meeting, scheduled for sometime next year, to finalize the treaty. But even if a deal is closed, it may still be years before tangible solutions reach Mekong nations.

In the meantime, many living along the Mekong are not waiting for global action.

Four plastic waste hotspots along the Mekong’s lower basin — Chiang Saen in Thailand, Phnom Penh and Tonle Sap lake in Cambodia and Can Tho in Vietnam — illustrate the efforts being made to address plastic pollution but also the ways plastic is changing the lives of river communities dependent on these waters.

“We’re addicted to plastics, now more than ever,” says Panate Manomaivibool, an assistant professor at Thailand’s Burapha University who has studied plastic waste in the Mekong’s transboundary regions. “Compared to the scale of the problem, attempts to fix it are tiny.”

THAILAND, MYANMAR AND LAOS | The Golden Triangle of the Mekong River

While the entire upper basin of the Mekong River flows through China, where the waterway is known as the Lancang, the Golden Triangle region between Thailand, Myanmar and Laos acts as the gateway to the lower basin.

The meanderings of the Mekong across these three countries act as a politically recognized natural border between nations, showcasing the Mekong’s transboundary nature and the politics involved in managing such a natural resource.

CAMBODIA | The ‘beating heart’ of the Mekong basin

After winding its way past Myanmar and between Thailand and Laos, the Mekong flows into Cambodia.

The nation’s capital Phnom Penh is situated at the confluence of the Mekong and its tributaries, the Bassac and Tonle Sap rivers. More than 100 kilometers (60 miles) northwest is the great Tonle Sap lake, known as “the beating heart of the Mekong” because of its unique flood pulse.

Rains from the annual monsoon season from May to October swell the size of the lake to roughly five times its usual size. The force of this flood reverses the direction of the Tonle Sap river, which is the only waterway in the world with this natural phenomenon. When the water level drops during the dry season, the river reverses once again.

VIETNAM | Where the Mekong meets the sea

Past Phnom Penh, the Mekong flows south to the Cambodia-Vietnam border and eventually reaches through the urban sprawl of Ho Chi Minh City.

Here, the mainstem of the Mekong River branches out into tributaries, swamps, and islands to create the Mekong Delta, known as Vietnam’s “rice bowl.” Nutrients flowing in from the Mekong have made the region’s fertile farmland part of a multimillion-dollar rice industry. But with plastics following the same path, those farms face increasing threat.

The delta’s largest city, Can Tho, has now become the epicenter for the region’s waste issues.

Funding for this reporting was provided by Dialogue Earth, an independent environmental reporting and analysis nonprofit. RFA retains full editorial control of the work.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Investigative.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The discovery of 46 illegal wells dug by Chinese migrants in the far western region of Xinjiang has intensified tension with Uyghur residents and disrupted the ecological balance of the region, people with knowledge of the situation told Radio Free Asia.

Fighting over water resources has been a source of friction for years between native Uyghurs and Chinese settlers in areas under the control of the state-run Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, or XPCC, called Bingtuan in Chinese.

Authorities investigated after residents in Korla, or Kuerle in Chinese, the second-largest city in Xinjiang, complained about the proliferation of wells on the outskirts of the city, a source in Xinjiang said, asking not to be identified for security reasons.

The wells, dug to grow cotton and vegetables, have drained vital underground reserves, he said.

As a result, authorities discovered 46 illegally drilled holes this year alone in Korla, a policeman in Bayingholin prefecture’s Public Security Bureau who had participated in this case in its early phase told Radio Free Asia.

The residents accused of drilling the holes without a permit are from the 29th Battalion of the Bingtuan’s 2nd Division and Chinese settlers living in an economic development region on the outskirts of Korla, the officer said.

“We have been working on water management, water control, and identifying water wells since February, and we continue to work on those issues,” the police officer said.

Little accountability

But legal authorities have slowed down reviewing the cases, and the suspects were released after brief questioning, the Uyghur source said, with officials using “stability” and “unity” as excuses to let them go.

RELATED STORIES

Chinese irrigation tunnel project in Xinjiang hits snag: too much water

Subsidies for Han settlers ‘engineering demographics’ in Uyghur-majority southern Xinjiang

More than 1 million lack clean water in Xinjiang’s Hotan prefecture

Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi faces water crisis fueled by migration

Authorities could not hold all perpetrators accountable because the activities likely involved Han Chinese, he said.

The Bingtuan is a state-run economic and paramilitary organization of mostly Han Chinese who develop the land, secure borders and maintain stability in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, or XUAR, where about 12 million mostly Muslim Uyghurs live.

Made up of 14 divisions, the Bingtuan is one of the foremost institutions of Han dominance and marginalization of Uyghurs and other indigenous ethnic groups in the region, according to the Uyghur Human Rights Project.

The well-drilling began in 2012 when demand for cotton surged, the Uyghur source told RFA.

Those who stole the water conducted their activities at night using advanced technology to pump it from a depth of 200 meters, or about 660 feet, he said.

“Since they drill these wells in a forested area, a place that people hardly go, it was hard to discover their illegal activities,” the Uyghur source said.

It costs about 150,000 yuan (US$20,600) to drill a well and make it operational, he said, an amount that Uyghurs would not likely be able to come up with.

Though the issue has sparked friction many times before, the government has protected the Han Chinese residents, he said.

The policeman initially said there were some Uyghurs among those held responsible, but when pressed for further information, he said most of those who drilled the illegal wells were Chinese who had settled in the area, including Bingtuan workers.

Staff at relevant government organization in Korla contacted by RFA declined to answer questions, but did not deny that Chinese settlers there had stolen water.

Drying up the land

The growing dependence on groundwater in the Korla area since the 1990s has reached a level that is disrupting the ecological balance, said the source familiar with the situation.

“We must control this or it will lead to a further decline in groundwater levels,” he said. “In some areas of our protective forests, the Euphrates poplars are withering and drying up.”

Peyzulla Zeydin, an ecological devastation researcher from Korla who now lives in the United States, told RFA that the misuse of water resources, including underground water, has severely impacted the region’s protective forests over time.

“In the 1990s, when we dug water wells, we could find water at just 10 meters,” he said. “Now, even at 30 meters, we can’t find water.”

“It’s getting worse because the underground water recycling system has been disrupted,” Zeydin said. “One of the main causes of the declining water levels is the growing population and the over-expansion of farmland. This has interrupted the natural underground water replenishment cycle.”

Zeydin said research indicates that the Bingtuan’s 1st Division battalions in the Korla area have overused and controlled the water resources there, leading to the drying up of Euphrates poplar trees along the lower streams of the Tarim River.

“The water level is dropping every day, and it has now reached a depth of 100 meters [330 feet],” he said.

Translated by RFA Uyghur. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Shohret Hoshur for RFA Uyghur.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Self-care is an act of resistance, especially when the fate of the free world depends on you. In the latest episode of Gaslit Nation, Andrea interviews Robert Schmuhl, author of Mr. Churchill in the White House. Their conversation reveals the fascinating dynamics between White House roommates Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. It also delves into the debate: did Churchill really see Lincoln’s ghost?

Two of the most powerful men of the 20th century, with towering egos and differing leadership styles, shared space in the White House during one of the most tumultuous periods in history. How did they manage? By treating self-care as sacred—a vital lesson for us today as we face a new era of America First and the rise of global fascism.

Schmuhl takes us behind the curtain, exploring Churchill’s struggles with depression and the personal toll of war. The episode doesn’t shy away from darker aspects, including Churchill’s role in the Bengal Famine. It’s a thoughtful, nuanced look at two men who shaped the world, yet weren’t immune to their own flaws and the overwhelming challenges they faced to liberate Europe and overcome the isolationism at home driven by fascist-aligned America First. Sound familiar?

Show Notes:

The song featured in this week’s episode is “Free” by Aaron Espe: https://open.spotify.com/track/3M7xHMsoIeNKLkrJ2wY4i6

Submit your song to be featured on Gaslit Nation: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeS7TftV6Vfnw-iasFLepL6FpIj_KFORDLrAlZGH3nLg7i8lA/viewform

Mr. Churchill in the White House The Untold Story of a Prime Minister and Two Presidents https://wwnorton.com/books/9781324093428

Due to the Christmas Eve holiday and the coziness of this conversation–it’s a perfect one to listen to around the fire or while wrapping presents–we’re publishing this episode a bit earlier than usual. Happy holidays!

This content originally appeared on Gaslit Nation and was authored by Andrea Chalupa.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Self-care is an act of resistance, especially when the fate of the free world depends on you. In the latest episode of Gaslit Nation, Andrea interviews Robert Schmuhl, author of Mr. Churchill in the White House. Their conversation reveals the fascinating dynamics between White House roommates Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. It also delves into the debate: did Churchill really see Lincoln’s ghost?

Two of the most powerful men of the 20th century, with towering egos and differing leadership styles, shared space in the White House during one of the most tumultuous periods in history. How did they manage? By treating self-care as sacred—a vital lesson for us today as we face a new era of America First and the rise of global fascism.

Schmuhl takes us behind the curtain, exploring Churchill’s struggles with depression and the personal toll of war. The episode doesn’t shy away from darker aspects, including Churchill’s role in the Bengal Famine. It’s a thoughtful, nuanced look at two men who shaped the world, yet weren’t immune to their own flaws and the overwhelming challenges they faced to liberate Europe and overcome the isolationism at home driven by fascist-aligned America First. Sound familiar?

Show Notes:

The song featured in this week’s episode is “Free” by Aaron Espe: https://open.spotify.com/track/3M7xHMsoIeNKLkrJ2wY4i6

Submit your song to be featured on Gaslit Nation: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeS7TftV6Vfnw-iasFLepL6FpIj_KFORDLrAlZGH3nLg7i8lA/viewform

Mr. Churchill in the White House The Untold Story of a Prime Minister and Two Presidents https://wwnorton.com/books/9781324093428

Due to the Christmas Eve holiday and the coziness of this conversation–it’s a perfect one to listen to around the fire or while wrapping presents–we’re publishing this episode a bit earlier than usual. Happy holidays!

This content originally appeared on Gaslit Nation and was authored by Andrea Chalupa.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As foreign powers look to shape Syria’s political landscape after the toppling of the Assad regime, the country’s Kurdish population is in the spotlight. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan continues to threaten the Syrian Kurdish YPG militia, which Turkey regards as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party militants who have fought an insurgency against the Turkish state for 40 years. Turkey’s foreign minister recently traveled to Damascus to meet with Syria’s new de facto ruler Ahmed al-Sharaa, the head of the Islamist group HTS. “Turkey is a major threat to Kurds and to democratic experiments that Kurds have been implementing in the region starting in 2014,” says Ozlem Goner, steering committee member of the Emergency Committee for Rojava, who details the persecution of Kurds, the targeting of journalists, and which powerful countries are looking to control the region. “Turkey, Israel and the U.S. collectively are trying to carve out this land, and Kurds are under threat.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Istanbul, December 23, 2024 – The Committee to Protect Journalists urges Turkish authorities to release journalists who were jailed in Istanbul on Sunday and allow the media to report freely.

On Saturday, Turkish authorities detained several dozen people, including journalists, at a protest against the December 20 killing of Kurdish journalists Jihan Belkin and Nazim Dashdan, who hold Turkish citizenship, in a suspected Turkish drone strike in northern Syria on December 20. The next day, an Istanbul court placed five journalists and two media workers in police detention pending trial and placed five other journalists under judicial control.

“The Turkish government is attempting to control the flow of news about Syria by intimidating the press, as evidenced by the arrest of journalists at a protest, the house arrest of Özlem Gürses, and other legal actions,” said Özgür Öğret, CPJ’s Turkey representative. “Turkish authorities must immediately release the imprisoned journalists and media workers, free Gürses, and allow members of the media to do their jobs without fear of retaliation.”

The journalists and media workers arrested at the Istanbul protest are:

Journalists were also detained at a similar protest in the eastern city of Van Friday but they were released.

State owned Anatolia Agency reported on Sunday that the chief prosecutor’s office in Istanbul is investigating independent news website T24 over its coverage of the reactions to the two journalist killings in Syria. Authorities are also investigating Seyhan Avşar, a reporter with independent news website Gerçek Gündem, on suspicion of terrorism propaganda and knowingly spreading misinformation for social media posts on Belkin and Dashdan.

In a separate incident on Saturday, an Istanbul court put journalist Özlem Gürses under house arrest pending trial on suspicion of demeaning the Turkish military over her comments on her YouTube channel regarding Turkey’s military presence in Syria. Gürses continues broadcasting from her home in Istanbul.

In another incident, the chief prosecutor’s office in Istanbul opened an investigation into the Bar Society of Istanbul for suspicion of terrorism propaganda and spreading misinformation due to its statement on Saturday calling for an investigation into the suspected Turkish drone killings of Belkin and Dashdan, and the release of journalists and others detained in Istanbul at the protest against their deaths.

CPJ emailed the chief prosecutor’s office in Istanbul for comment but did not receive a reply.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by Committee to Protect Journalists.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

New Delhi, December 20, 2024—Indian journalist Anand Mangnale is the target of an online smear campaign that began on December 5 when Nishikant Dubey, a parliament member with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), linked Mangnale to an effort to “derail” the Indian government through foreign funding in Parliament.

“Investigative journalism is crucial for uncovering corruption and holding power to account,” said Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. “Efforts to discredit public interest reporting and target journalists through smear campaigns create a chilling effect on press freedom. CPJ urges the Indian ruling party BJP to respect journalists’ role in democracy and refrain from weaponizing their authority to intimidate the press.”

Mangnale, the South Asia regional editor at the investigative news outlet Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), is known for his reporting on alleged corporate malfeasance, financial irregularities, and corruption involving the Adani Group, one of India’s largest conglomerates.

The official BJP account on social media X amplified Dubey’s claims, alleging that Mangnale fundraised for the opposition party and gave “Chinese money” to a person accused of involvement in the 2020 Delhi riots.

The BJP cited a report by French news outlet Mediapart in its claim; Mediapart refuted the allegations, saying the BJP “wrongly exploited” its report to discredit independent journalism.

These developments come after the U.S. Justice Department indicted Gautam Adani, chairperson of the Adani Group, and his associates in November 2024 for allegedly bribing Indian officials to secure contracts and misleading U.S. investors about the company’s anti-corruption practices.

Mangnale told CPJ that he anticipates these recent developments could trigger new legal cases or intensify existing ones against him.

In May 2024, Indian authorities summoned Mangnale for questioning about alleged involvement in terrorism in connection to his work with Newsclick. Formal charges have not yet been filed. He was also among several high-profile journalists in India to be targeted with Pegasus spyware.

CPJ’s emailed requests seeking comments from Dubey and BJP spokesperson Sambit Patra did not receive a response.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

We continue to look at the U.S. health insurance industry and how patients can fight back against their providers with advocate Elisabeth Benjamin, vice president of health initiatives at the Community Service Society of New York and co-founder of the Health Care for All New York campaign. She says her advice for patients is to always appeal denials and to seek outside help when possible, including advocacy groups like hers and external review boards. She also stresses that much of the chaos of the U.S. health system is due to corporate greed. “Everyone has an incentive to charge more,” says Benjamin. “If we had Medicare for All, we wouldn’t be paying as much, and we would probably have much better health outcomes.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Amnesty International and was authored by Amnesty International.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In recent years, Binh has become used to living in a constant state of fear. Like so many who work in Vietnam’s civil society, the 44-year-old is paranoid that on any given day she could be arrested simply for going to work.

“Everyone now has a sense of being alert,” she told RFA over the phone in November. “People I know have been arrested for unknown reasons.”

Binh, who asked that a pseudonym be used for security reasons, has spent more than 20 years working on humanitarian aid for both local and international non-governmental organizations in Vietnam. At each one she has dodged intimidation and crackdowns meted out by Vietnam’s ruling Communist Party. But lately the problem has grown markedly worse.

While working for one international NGO, Binh explained that the entire staff would be summoned to the offices of the Vietnam Union of Friendship Organization, the agency that manages international NGOs, for an “interview” every three months.

“They would ask us where we had travelled recently and what we were doing. It was very weird. It was obvious they wanted us to know we were under supervision,” Binh said.

Other times, said Binh, police would follow her and her colleagues while they worked in the field.

Even the UN has experienced “strict surveillance” and pushback, according to Binh, who has experience partnering with several of its agencies.

“There were times where they shut down the electricity or told the venue owner not to rent to them,” Binh said. In response to RFA, the office of the UN Resident Coordinator in Vietnam, which manages the country team, said that “the UN collaborates with the Vietnamese government, civil society, and other international partners” to achieve its goals, but did not comment on any crackdowns the agencies have faced.

Binh has done everything she can to protect herself and so far it has worked, but others, including her colleagues and her close friends, have not been as fortunate.

Over the past four years, nearly a dozen NGO workers have been arrested or detained simply for doing their job, according to the Vietnam human rights organization Project 88. At least four remain behind bars today, along with more than 175 other activists.

These arrests – many of them carried out on charges of tax evasion or other allegations that legal monitors say are politically motivated – are part of a greater crackdown by the government to restrict civil society in Vietnam.

A series of oppressive rules, many of which are kept hidden, have provided the foundation for these efforts as the Communist Party seeks to tighten its grip on power.

One, and arguably the most draconian, of these is Directive 24, which was issued in July 2023 and casts all foreign cooperation as a national security threat amid the country’s increasing globalization.

The secret directive, which was obtained by Project 88 earlier this year and has never been released by the government, details opposition to free expression, international aid, unions, and even foreign travel. The impact, say experts, is an effective criminalization of activism.

In October, the government reinforced these measures with Decree 126, which added further restrictions on forming any kind of association in the country.

The crackdowns have also been rolled out alongside a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that has brought much of civil society to a standstill by fostering a climate of fear that has left politicians unwilling to approve projects and funding.

Over the last four months, RFA spoke with over a dozen activists, NGO workers, international donors, diplomats and experts to understand how government orders and subsequent crackdowns have intensified and what it has meant for those working in civil society in the country.

Fear of foreign influence

Civil society wasn’t always a target of the government in Vietnam. A decade ago, many had a much more optimistic outlook.

Nguyen Tien Trung, a pro-democracy activist now based in Germany, was arrested in 2009 for protesting against the Communist Party. He was released five years later at a time when support for civil society looked very different to how it does today.

“When I was released from prison in 2014, civil society organizations mushroomed in Vietnam. Many organizations, both registered and unregistered with the Vietnamese communist government, were operating freely,” said Trung.

But around 2016, circumstances started to change. Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung announced his retirement and Nguyen Phu Trong, who was serving as General Secretary of the Communist Party, was re-elected for a second term. Trong died earlier this year.

Unlike Dung, who had been relatively sympathetic to civil society, Trong took a very different approach. He disagreed with the cozy relationships that Tan Dung had cultivated with the West and began rolling out a series of measures to restrict foreign influence.

Vietnam has a wide range of organizations that operate at different levels, from informal, non-registered groups at the local level to massive, international NGOs, or INGOs, like Save the Children and Oxfam.

Most INGOs are registered under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while domestic NGOs are normally registered with the Ministry of Science and Technology. But the measures introduced under Phu Trong sought to expand the government oversight over these organizations.

RELATED STORIES

New decree keeps associations under control of Vietnam’s Communist Party: Project 88

US must not shun rights in Vietnam ties, lawmakers say

The deepening ‘securitization’ of Vietnamese politics

Beginning in 2020, the government imposed a series of decrees and decisions to block access to foreign funding and increase restrictive oversight in what two United Nations special rapporteurs said established “unreasonably burdensome requirements” for operations.

“Communist Party leaders want to maintain their power monopoly. They are wary of foreign influence that could destabilize its control. International NGOs and foreign entities often promote democratic values and human rights, which the Communist Party views as threats to its one-party rule,” said Trung, the democracy activist.

However, he noted that the concerns are specifically centered on Western influence, while China and Russia, for example, serve as “models for the Communist Party to follow.”

The government ministries that oversee NGOs in Vietnam did not respond to RFA’s request for comment for this article.

Shrinking the space

Numerous NGOs have been forced to shut down in recent years amid this environment.

Among them are Towards Transparency, Vietnam’s branch of Transparency International, which closed its doors in late 2021 due to security concerns. Shortly before, the website’s domain had been revoked by municipal authorities, in what many considered a threatening move, after a map was published that excluded contested islands in the South China Sea.

LIN Center for Community Development, an umbrella network of 400 nonprofits, announced it would close in November 2022 without specifying the reasons, and the Institute of Technology Research and Development, or SENA, was forcibly dissolved in July 2023, a year after its director was arrested and charged with “abusing democratic freedoms” for submitting recommendations to improve the Communist Party.

The government has also targeted individuals, notably through the use of the tax law. Laws around tax evasion are vague and can be manipulated into prosecuting anyone that the government wants stopped, said Trung.

As a result, “the fear of being arrested under the charge of ‘tax evasion’ has instilled a sense of caution, if not outright paralysis, in the sector,” he said.

One of the most high-profile of these cases in recent years was the arrest of environmental activist Hoang Thi Minh Hong in May 2023. She was sentenced to three years in prison on tax evasion charges, but was released early in September of this year.

Project 88 found that “the Vietnamese government has a history of using tax evasion charges to prosecute dissidents who cannot be persuasively charged under national security provisions of the criminal code”.

Nguyen Quang A, a prominent human rights activist in Vietnam and the former director of the now-dissolved Institute for Development Studies, told RFA that he has been arrested for tax evasion “at least four or five times” but always as a cover for dissident activity.

Other laws have also been weaponized. In April, Nguyen Van Binh, who served as director general of the Ministry of Labour’s legal department, was arrested and prosecuted for allegedly disclosing state secrets.

He had sought to help grant workers the rights to form unions, which, with the exception of the one state-affiliated union, are banned in Vietnam.

Binh was seen as an “ally” to groups such as Stitch, a Dutch nonprofit that worked on labor rights in Vietnam and his arrest was seen as “a signal that the direction he was taking was not the way to go,” according to a senior source familiar with the organization.

Following his arrest, Stitch ceased its activities in Vietnam.

“There was also fear of repercussions because of that signal for those involved in Stitch,” the source said.

The Blazing Furnace

The crackdowns are only one set of challenges that NGOs in Vietnam have been forced to navigate. A controversial anti-corruption campaign called “blazing furnace” has made it harder than ever for civil society to get government sign-off on everything from travel to funding.

Since it was launched in 2013, the government has turned itself inside out, arresting officials at all levels, including senior members of the Politburo and government ministries. As of 2023, nearly 200,000 party members have been disciplined as part of the campaign.

While the campaign successfully brought Vietnam up to 83 from 113 on the Corruption Perceptions Index, it has also created a chilling effect for legitimate work, advocates say.

“It isn’t clear to officials what kinds of activities could get someone into trouble so everyone is on high alert at all times,” said Minh, a longtime activist who asked that a pseudonym be used for security reasons.

“The biggest impact from the anti-corruption campaign is that government officers don’t want to work anymore, they don’t want to approve civil society. They keep silent because it’s easier to say no.”

Yet that means that in the last three years Vietnam has forfeited approximately $2.5 billion in foreign aid. Another $1 billion is currently being held waiting for approval.

Much of that funding was earmarked for things like development and infrastructure projects, in which UN or EU agencies sometimes partner with local organizations.

A former senior Western donor official told RFA that a lot of local organizations “no longer want to take foreign money because it causes too many risks,” which has forced them to downsize operations.

Finding alternatives

To operate, civil society groups have found some workarounds. One way is by registering as social enterprises – a hybrid between a charity and a for-profit enterprise – instead of an NGO. Some groups have found this easier for operating, but it means having to pay more taxes.

Another option is to develop closer relationships with the government, including by funding government advocacy initiatives, in order to “have protection.”

“They aren’t directly bribing the government, but they are putting a lot of money and investment into building up those relationships in order to avoid any issues,” Binh said.

But relief from these options is not ideal and likely temporary. Those working in Vietnam’s civil society are concerned that the environment will only keep getting worse.

After Phu Trong’s death in July, he was succeeded by To Lam, a longtime party operative who has held senior positions in government for decades.

As Minister of Public Security, he orchestrated many of the crackdowns against civil society, including the use of tax evasion as a way of silencing dissidents.

“To Lam spent all his life in the police. He views all organizations that are not under the control of the Communist Party as potential enemies,” said Trung, the pro-democracy activist.

“I have no doubt that he will continue to suppress the democratic and civil society movements,” he predicted.

Edited by Abby Seiff and Boer Deng.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Allegra Mendelson for RFA Investigative.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

New York, December 18, 2024—The Committee to Protect Journalists condemns a Kyrgyzstan court’s decision upholding convictions against four journalists from anti-corruption investigative outlet Temirov Live, two of whom were sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

On Wednesday, the Bishkek City Court upheld an October 10 first instance court decision sentencing Makhabat Tajibek kyzy to six years in prison, Azamat Ishenbekov to five years in prison, and reporter Aike Beishekeyeva and former reporter Aktilek Kaparov to three years of probation. Prosecutors did not appeal the acquittals of seven other current and former Temirov Live staff.

“Temirov Live’s bold anti-corruption coverage has made it the Kyrgyz government’s number one target. By upholding the outrageous prison sentences against director Makhabat Tajibek kyzy and presenter Azamat Ishenbekov, Kyrgyz authorities are confirming that they have no response to the outlet’s reporting but repression,” said Gulnoza Said, CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia program coordinator. “Authorities in Kyrgyzstan should immediately release Tajibek kyzy and Ishenbekov, not contest their Supreme Court appeals and the appeals of journalists Aike Beishekeyeva and Aktilek Kaparov, and end their campaign against the independent press.”

Temirov Live founder Bolot Temirov told CPJ from exile that the journalists plan to appeal their convictions to Kyrgyzstan’s Supreme Court.

Kyrgyz police arrested 11 current and former staff of Temirov Live, a local partner of the global Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), in January on charges of calling for mass unrest, accusing the outlet of “indirectly” making such calls by “discrediting” authorities in their videos.

Authorities previously deported Temirov, an international award-winning investigative reporter, and banned him from entering Kyrgyzstan for five years in retaliation for his work.

In November, CPJ submitted a report on Kyrgyz authorities’ unprecedented crackdown on independent reporting under current President Sadyr Japarov to the United Nations Human Rights Council ahead of its 2025 Universal Periodic Review of the country’s human rights record.

On Tuesday, Japarov accused U.S. Congress-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Kyrgyz service and “five or six other sites” of “using freedom of speech as a cover” to spread false information and warned them to “be careful” with their reporting on corruption.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“And hope here, I don’t think it’s passive. It is active. It’s a form of resistance against despair. And it must be paired with a political imagination, that belief that we can build the future.”

–Wasim Almasri, Director of Programs, The Alliance for Middle East Peace

In this important conversation, Andrea and Terrell speak with Avi Meyerstein, Founder and President of the Alliance for Middle East Peace (ALLMEP), and Wasim Almasri, Director of Programs based in the West Bank city of Ramallah. They discuss what a meaningful path to peace looks like for Israelis and Palestinians, how to achieve it, the priorities the outgoing and incoming U.S. administrations must focus on, and the pending ceasefire deal, which has seen a resurgence of promising negotiations in recent days.

If you’re looking for defiant hope and a light to show the way in these dark times, listen to the team at ALLMEP who have been hard at work planting powerful seeds of change. For more on their work, check at the link at the top of the show notes.

Want to enjoy Gaslit Nation ad-free? Join our community of listeners for bonus shows, ad-free episodes, exclusive Q&A sessions, our group chat, invites to live events like our Monday political salons at 4pm ET over Zoom, and more! Sign up at Patreon.com/Gaslit!

Thank you to everyone who supports the show–we could not make Gaslit Nation without you!

Show Notes:

The Alliance for Middle East Peace: https://www.allmep.org/

Hopes for Gaza ceasefire-for-hostages deal rise Israeli officials, Hamas sources, and US and Arab figures say deal may be within reach – perhaps within days https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/17/israeli-negotiators-head-to-qatar-as-hopes-rise-for-gaza-hostage-deal

This content originally appeared on Gaslit Nation and was authored by Andrea Chalupa.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

Representatives of the Thai government and Myanmar junta are due to discuss a series of militia posts along the two countries’ common border that Thailand says are in its territory, Myanmar’s junta spokesperson said.

The United Wa State Army, or UWSA, militia force controls autonomous regions in Shan state including one on the border with Thailand, which says nine of the group’s outposts are in Thai territory and must be removed.

The confrontation has raised fears of violence between what is probably Myanmar’s most powerful militia force, which is also accused of massive involvement in the drug trade, and the Thai army.

Myanmar junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun told Myanmar state media on Monday that military representatives were due to meet the Thai government and the issue of the UWSA camps would be tackled.

“Mainly border issues and matters related to cross-border crime will be discussed. We will discuss cooperating in order to enact border stability and fight criminal violations,” the junta spokesperson said.

He did not give a date for the talks.

Thai officials, at a meeting with UWSA representatives in the Thai city of Chiang Mai in November, gave the UWSA a deadline of Dec. 18 to withdraw from the posts, media reported.

But Wa officials dismissed the Thai demand on Dec. 7, and said the matter should be taken up in government-level discussions, adding that the Thai army was “not their enemy.”

The UWSA emerged from the break-up of the Communist Party of Burma in 1989, when its rank-and-file fighters, drawn largely from the Wa ethnic minority, mutinied against the party’s aging leadership.

The UWSA struck a ceasefire with the Myanmar military in exchange for autonomy in zones on the borders of both China and Thailand.

Despite being what is largely seen as the best equipped militia force in Myanmar, it has not joined the anti-military insurgency that has swept the country since the generals ousted an elected government in a 2021 coup.

International anti-narcotics agencies say the UWSA has been heavily involved in the opium and heroin trade for decades and took up the manufacture of methamphetamines on a massive scale in more recent years.

The UWSA, which is known to have close contacts with China, denies involvement in drugs.

The nine disputed border outposts that the UWSA says are in its “171 military region” are in the Shan state townships of Tachileik, Mongsat, Mongton, Hway Aw and Pong Par Kyi, along the northern Thai border.

Translated by Kiana Duncan. Edited by RFA Staff.

RELATED STORIES

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.