Of all the sources of culture shock I might have anticipated after my partner and I bought a home in 2022 in northern Italy, trash collection never crossed my mind. I didn’t know going in that Italy had become the top overall recycling country in the EU and one of the best for household-level recycling — in part by relying on those households to do a lot of the work. I quickly got my crash course.

In short: In our town, Lesa, we have to sort trash into six categories: “wet” (compost), plastic, glass, paper, metal, and “dry” (aka everything that isn’t recyclable, which isn’t much). Like our neighbors, we keep six bins in our kitchen, one for each category, and our kitchen is in fact designed around this need. (There’s yet a seventh “green” bin for yard waste, but that generally goes in the shed.) One type gets picked up every day except Sunday, meaning we have to put some form of trash out nearly every night. Some categories go in government-issued bags, while “wet” must be in biodegradable bags, glass goes in an unlined bin, and paper goes into designated reusable open bags.

It was a lot to learn. But once I got the hang of it, the recycling and trash sorting efforts stopped feeling like an inconvenience and became something like second nature. I’d go so far as to say it felt satisfying to contribute in this way on a daily basis.

Thirty years ago, Italian households mostly took out the trash in one go. Since then, nearly all residents of Italy have at some point reprogrammed their habits, just as I had to. This behavior shift, along with investment in domestic waste-processing infrastructure, has been integral to Italy’s recycling success.

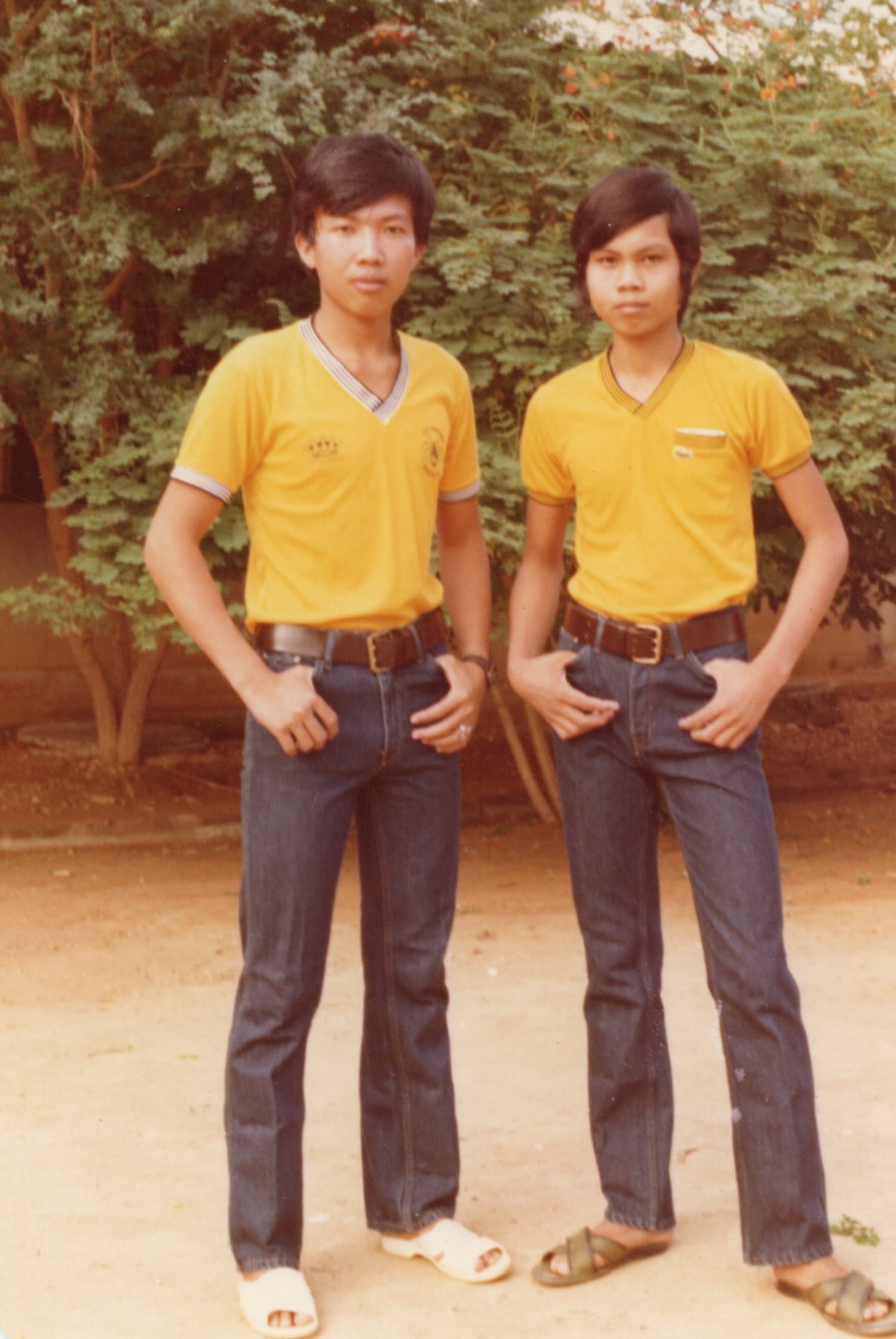

The household bin arrangement: Most of the receptacles fit neatly into drawers and cabinets, with the exception of the paper bin. Sarah Stodola

Getting residents on board

Italy’s transformation into a recycling powerhouse began in 1997 with the Ronchi Decree, a law that created a compulsory minimum recycling rate of 35 percent, placed the responsibility for achieving it on municipalities, and empowered them to manage both the logistics and financing of the subsequent efforts. The law came about after a waste-management crisis in the region around Milan brought the issue of trash processing to the forefront of Italian politics. Most municipalities today set their own local waste collection tax rates (known as the TARI), while recently a few have moved to a “pay-as-you-throw system,” with fees based on the amount of waste a household generates.

The Ronchi Decree also placed responsibility for trash sorting at the household level — as opposed to a single-stream approach, where waste gets sorted at facilities — with measures to get residents on board built into the legislation. Marco Ricci, a circular economy expert in Italy who worked with the national government on the legislation’s rollout, points to several factors that helped shift individual behavior, including a new door-to-door collection system and, in most localities, giving residents the necessary bins and bags free of charge. Still, people needed convincing, with concerns about both costs and the program’s effect on their time and their kitchens.

“The resistance was approached in a very simple and effective way: a lot of local meetings,” Ricci said. He spent a few years going from town to town, working with mayors and other experts to explain the new scheme to residents. This federally coordinated outreach campaign ultimately reached about 50 percent of the Italian population, he said.

Regional implementation, rather than relying on a national system, was key. “It was fundamental,” Ricci said. “Italians are really closely linked to their community, and we made use of this community feeling.” Because small communities were easier to communicate with directly, rural areas ended up adopting the new system more quickly than the big cities. In addition, both local politicians and residents proved more willing to learn from others and hold neighbors accountable. As a result, a domino effect swept the less populated areas of Italy: Once people saw their neighbors using the new bins, they wanted their own, and once mayors saw neighboring towns finding success in recycling, they wanted in on it, too.

Fines for improper waste disposal were part of the equation, but equally important were softer incentives, such as the policy of providing residents a set allotment of bags for nonrecyclable trash, which is only picked up if it’s in those bags. If someone were to use up her allotment too quickly by including too many recyclable items, she’d be out of luck until the next allotment. This is all the motivation most residents need to sort their trash properly.

In 2006, additional legislation mandated raising Italy’s minimum recycling rate to 65 percent of all household waste, a requirement that went into effect in 2012 — years before the EU set the same standard in 2018. By then, Italy was well ahead of the game.

Individual change, collectivized

I met Maria Grazia Todesco while doing some volunteer translating for a local museum. She has lived in Italy her whole life and currently resides in Solcio, a town neighboring mine. Since she’s experienced Italian trash collection both before and after the changes of recent decades, I was curious to get her take. She told me that the new system definitely requires more effort and attention — but to her at least, it feels well worth it. “With a little goodwill, the task becomes easier,” she said. “I think it was a necessary choice and very useful if we want to somehow safeguard our planet. Each of us individuals can do a lot to achieve the goal.”

Lesa and Solcio are in the wealthier northern part of the country, where recycling efforts have long been among the best in Europe. In recent years, Italy’s southern regions have been making notable progress as well — despite the need for more processing facilities in the south and challenges with a wider recycling industry that resists close monitoring, similar standards and enforcement mechanisms now exist throughout the country.

Still, the need for reinforcement and education remains. Erum Naqvi, a friend of mine back in New York who also owns a home in Lesa, said she initially handled her trash the same as she would back in the States — which is to say, not thinking much about tossing most things into the bin destined for the landfill. But one afternoon, a local police officer showed up to give her a warning about sorting, bagging, and putting it out correctly. Naqvi quickly got herself up to speed. She is careful about sorting correctly and keeps the trash pickup schedule pinned next to her door, consulting it every day.

Naqvi has now changed her habits even back home. “Coming back to New York, I felt so guilty not doing it [to the same degree]. It’s instilled in me a more positive approach toward recycling,” she said.

For me, it’s been revelatory to witness the collective impact of individual efforts, and to participate in it. Nearly every evening in Lesa, households place the appropriate bags or bins out next to their doorsteps, creating a consistent tableau throughout town. Looking up the next morning’s category, then preparing it and putting it out, has become part of my after-dinner routine. Early every morning, collection trucks built small enough to pass through the town’s ancient, narrow streets arrive before most residents are awake — except on glass collection day. Those trucks arrive later so as to not wake residents with the inevitable clatter of glass as it’s dumped from the bins.

In the winter months, the nonrecyclable trash gets collected just once every two weeks. Nothing has surprised me more than finding myself struggling to fill even one small bag during that time, so thorough is my sorting of the recyclables. That’s a common observation — and a sign that individual action, like trying to produce less garbage, becomes a whole lot easier when the system is designed to support it.

— Sarah Stodola

More exposure

- Read: more about rising recycling rates and circularity in the European Union (Eunews)

- Read: about the definition of “recycling,” and the difficulty with achieving true circularity for certain products, especially plastics (Grist)

- Read: about the origins of the chasing-arrows recycling symbol — and how that symbol came to lose its meaning (Grist)

- Read: about New York City’s recent efforts to mandate composting (Grist), and why the city is now pausing fines for noncompliance (NBC New York)

- Read: about some common misconceptions with recycling, and how an overemphasis on recycling can obscure more important efforts to reuse and reduce (The Conversation)

A parting shot

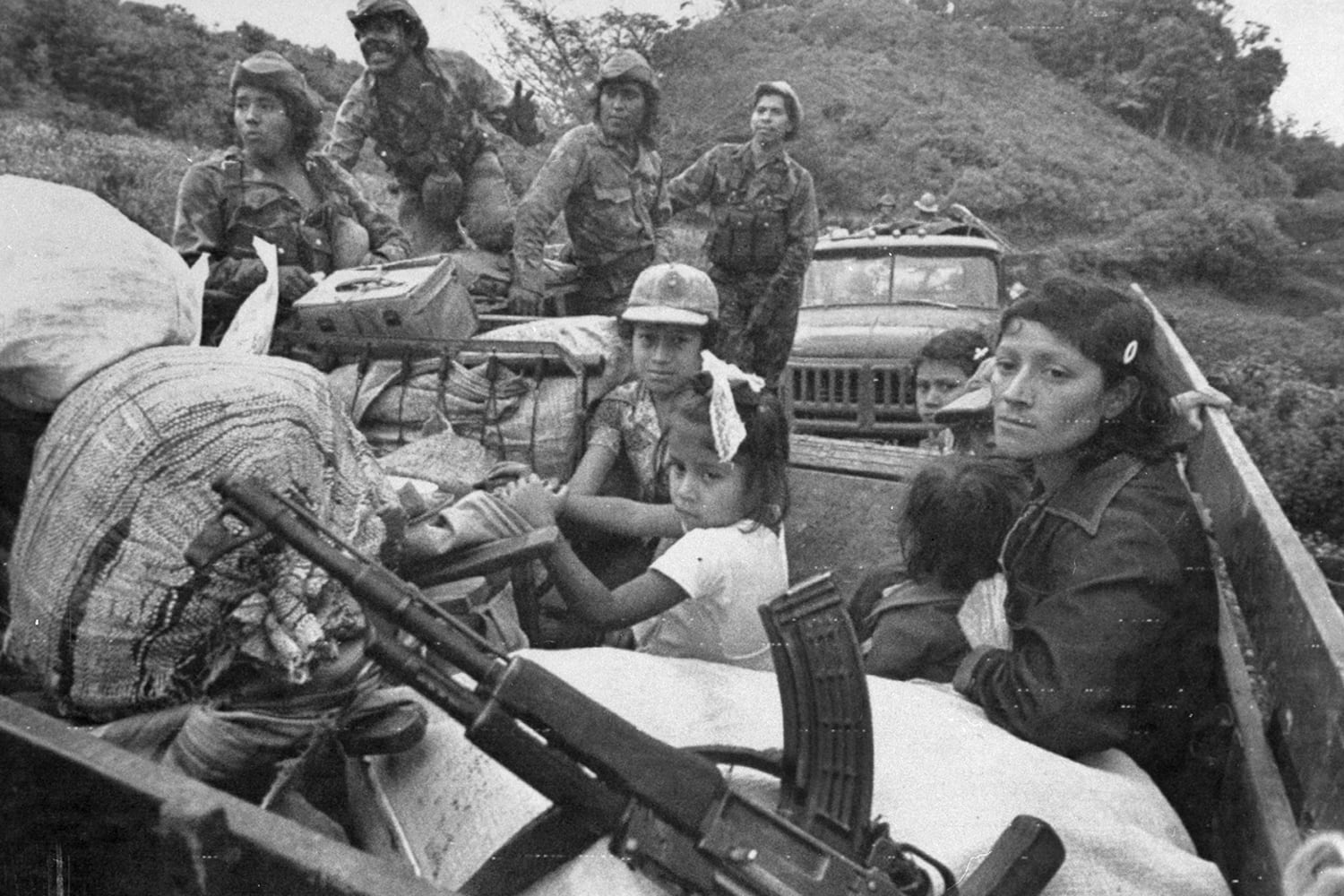

Waste management has long been a troubled industry. When we as individuals “throw something away,” we’re really just sending it somewhere else for someone else to deal with — that same paradigm can play out on a global stage, even going so far as cross-border “waste trafficking.” One of this year’s prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize recipients, announced this week, helped challenge such a scheme between Italy and Tunisia. In 2020, Italy illegally sent 282 shipping containers filled with common household garbage to Tunisia. Thanks to prize winner Semia Gharbi, and other advocates, the majority of the waste was returned in February of 2022 to the same Italian port where it originated, as shown below — and the scandal also led to tightened regulations in the EU.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Italy got its citizens — and me — to adopt a rigorous recycling scheme on Apr 23, 2025.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Sarah Stodola.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.