This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post Democratic bill aims to stop Trump-Musk power grab; AG Bonta acts to protect transgender and undocumented students from Trump executive orders – February 4, 2025 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

New Delhi, Feb 4, 2025—The Committee to Protect Journalists calls on the Indian government to end its weaponization of regulatory measures targeting independent journalism following a decision to revoke The Reporters’ Collective’s nonprofit status and the tax exempt status of The File.

“Journalism is a public service. The Indian government should not abuse regulatory processes to target investigative journalism,” said Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. “The government must immediately reverse these orders against The Reporters’ Collective and The File, which could set a dangerous precedent for other non-profit media in India and severely undermine public interest journalism.”

The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) said in a January 28 statement that the loss of its nonprofit status “severely impairs” its ability to do work and “worsens the conditions” for independent journalism in the country.

The revocation of a nonprofit status means entities will be taxed as a commercial entity, subjecting donations to taxation, which could discourage potential funding. The tax could potentially be applied retrospectively. TRC is known for its investigative reporting on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling government, ranging from corruption, government accountability, to allegations of corporate cronyism, and unethical business practices against the Adani Group, one of India’s wealthiest conglomerates.

The directive against TRC follows a disturbing pattern of financial and legal pressures on independent media. In December 2024, the Bengaluru-based Kannada website The File, which has conducted investigations into all political parties in the southwestern state of Karnataka, also faced a similar tax order, which was reviewed by CPJ. The order revoked its tax exemptions, deeming its activities commercially oriented despite its public interest reporting.`

In February 2023, income tax authorities in India searched BBC offices in New Delhi and Mumbai as part of an income-tax investigation, weeks after the broadcaster aired a documentary critical of Modi.

CPJ contacted the commissioner of Central Board of Direct Taxes and the exemption commissioner in Delhi and tax authorities in Bangalore about TRC and The File’s cases but did not receive responses.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Amnesty International and was authored by Amnesty International.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Mexico City, January 31, 2025—The Committee to Protect Journalists calls on Mexican authorities to swiftly complete an investigation into the killing of journalist Alejandro Gallegos León, an academic and evangelical pastor based in the state of Tabasco, who was reported missing on January 24, according to a report. His remains were found the next day in the town of Cárdenas, according to news reports.

“The killing of Alejandro Gallegos comes weeks after the killing of journalist Calletano de Jesús Guerrero, underscoring the ongoing crisis violence and impunity journalists in Mexico face,” said Jan-Albert Hootsen, CPJ’s Mexico representative. “Unless Mexican authorities take all appropriate steps to find Gallegos’ attackers, president Claudia Sheinbaum’s commitment to protecting press freedom continue to ring hollow.”

Gallegos, 51, was the editor of La Voz del Pueblo, a news website based on Facebook, according to newsreports. He also worked as a teacher at the Alfa y Omega Presbyterian University in Tabasco and as a lawyer, they added.

La Voz del Pueblo mostly publishes short news stories and videos on regional politics in Tabasco. Despite news reports of a recent spike in criminal violence in the state, the website did not extensively cover that topic. Its recent articles on politics mostly cover press events in a neutral tone.

It is unclear whether Gallegos had received threats. CPJ was unable to find contact information for his family. Messages to La Voz del Pueblo via Facebook and calls to the Alfa y Omega University for comment were not immediately answered.

The Tabasco state prosecutor’s office (FGE) said in a statement released on X on January 25 that it opened an investigation, without providing further details. Several phone calls by CPJ to the FGE to request comment were not answered.

The Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, a federal government agency that provides protective measures to the press, said in a January 25 statement on X that Gallegos was not incorporated in a federally sanctioned protection program.

On January 29, Tabasco governor Javier May said on X that a suspect in the case had been arrested. He did not provide further details. Several calls by CPJ to the governor’s office were not answered.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

More than 1,000 civilians have fled Rakhine state’s capital Sittwe and nearby areas in western Myanmar, fearing heavy artillery attacks as tensions rise between junta forces and the Arakan Army, an ethnic armed group that has advanced on junta positions, residents said Friday.

Ongoing exchanges of fire between junta soldiers and the Arakan Army, or AA, in nearby villages, have prompted residents to seek safe havens out of concern that they might be hit by bombs, sniper fire, drone strikes or air strikes, should the conflict escalate.

Of the 17 townships in Rakhine state, 14 are under the control of the AA, leaving only three — Sittwe, the military council’s regional headquarters, Kyaukphyu and Munaung — still in the hands of the military junta.

Observers believe that the AA soon could launch an offensive against Sittwe.

And because of this, civilians say they fear getting trapped in the crossfire of heavy artillery used by junta battalions based in Sittwe if the AA strikes.

Sittwe is crucial for the junta — which seized control of Myanmar in a 2021 coup d’état — not only as a source of much-needed revenue and foreign currency, but also for its role in Myanmar’s oil and gas trade via the Indian Ocean.

Besides Sittwe, people in Rathedaung, Pauktaw and Ponnagyun —townships close to Sittwe — are also leaving their homes out of fear of direct attacks, said a Rathedaung resident who spoke on condition of anonymity for safety reasons.

“Some already fled from Sittwe township, but now they find themselves forced to flee again, adding to their hardships,” the person said. “Many are struggling due to a lack of warm clothing for winter and severe shortages of basic necessities after being displaced.”

The junta’s blockade of transportation routes in Rakhine state, which has made travel for displaced civilians difficult, has compounded the situation, they said.

Sittwe residents told RFA that the AA has surrounded the city with a large number of troops while the military junta has fortified its positions, increasing its military presence with battalions outside the city, in areas of Sittwe, and at Sittwe University, in preparation for a defensive stand.

RELATED STORIES

EXPLAINED: What is Myanmar’s Arakan Army?

Myanmar junta troops tell residents of villages near Sittwe to leave by Friday

Arakan Army’s gains enough to enable self-rule in Myanmar’s Rakhine state (COMMENTARY)

Myanmar’s Arakan Army draws closer to region’s capital

Additionally, thousands of Rohingya — a stateless ethnic group that predominantly follows Islam and resides in Rakhine state — have been given military training by the junta, sources said.

“The army is shooting; the navy is also shooting,” said a Sittwe resident. “People are afraid. They don’t know when the fighting will start.”

The AA has already fired heavy artillery and used snipers. Local news reports on Jan. 27 indicated that daily exchanges of fire were occurring between the ethnic army and junta forces, including the use of attack drones.

Attempts by RFA to contact both AA spokesperson Khaing Thu Kha and junta spokesperson and Rakhine state attorney general Hla Thein for comment on the issue went unanswered by the time of publishing.

Human rights advocate Myat Tun said he believes the AA will resort to military action in Sittwe if political negotiations fail.

“The situation in Sittwe is escalating,” he said. “The AA is preparing to take military action if political solutions are not reached.”

Translated by Aung Naing for RFA Burmese. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Myanmar.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on ProPublica and was authored by ProPublica.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post Congo fighting threatens civilians and rights; Democrats mull last election as they choose new leader – January 31, 2025 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

On the Thai-Myanmar border, sick patients are being sent home from hospital. In Laos, school meals have been interrupted. And in Cambodia, hundreds of staff at the agency responsible for clearing land mines have been furloughed.

The U.S. State Department on Friday announced a 90-day freeze on nearly all foreign aid, followed one day later by a suspension of global demining programs, according to the New York Times. The pause is intended to give the State Department time to review programs “to ensure they are efficient and consistent with U.S. foreign policy under the America First agenda,” according to the announcement notice.

In the days since, stop-work orders have been sent by the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID, to local implementing partners ranging from media organizations to health clinics.

The U.S. is one of Southeast Asia’s largest providers of aid, and its withdrawal will be felt most in the region’s poorest nations: Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. Japan provides more to those countries, but the U.S. has gradually increased aid to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar from $380 million in 2015 to almost $520 million in 2022, according to Grace Stanhope, a research associate at the Lowy Center who works on its Southeast Asia Aid Map.

Groups that work with Tibetans, Uyghurs and North Koreans are also feeling the pinch. These include the Tibetan government-in-exile, which is based in Dharamshala, India, and which supports the diaspora community.

On Tuesday, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a waiver exempting “life-saving” humanitarian aid, including medicine, shelter and food aid.

While both the order and State Department notice make clear that programs can restart once reviews are complete, the impact in many countries has been immediate. RFA spoke with government officials and NGO staffers to better understand what an aid freeze looks like on the ground.

The Department declined to respond to specific questions over email.

Myanmar:

Saturday marks the fourth anniversary of the Feb. 1, 2021 coup, in which the military overthrew the democratically elected government, imprisoning its top leadership. The spiraling civil war that has ensued has displaced 3.4 million people and expanded the refugee population in neighboring Thailand.

Within the days of the stop-work order, a range of U.S.-funded healthcare services began grinding to a halt. In fiscal year 2024, which runs from Oct. 1, 2023 to Sept. 30, 2024, the U.S. provided $141 million in humanitarian aid to Myanmar.

“In-patients at the refugee camp hospital were discharged and told to return home because health workers have been suspended from their duties,” a health worker speaking on the condition of anonymity due to security reasons told RFA. Volunteers were trying to relocate critical patients and send pregnant women in labor to external hospitals, The Irrawaddy reported.

The worker added that approximately 20 civil relief groups providing healthcare with USAID assistance along the Thai-Myanmar border are now at risk of being suspended. A Reuters report said the International Rescue Committee, which funds the clinics, told them they would have to shut down by Friday.

Along the Thai-Myanmar border, nine refugee camps provide shelter to nearly 140,000 people.

Inside those camps, schools have already “suffered a huge impact,” said Banyar, founder of the Karenni Human Rights Group. Teacher salaries would have to be halted and a pause on the purchase of textbooks and other school supplies, he said.

Those who work on HIV/AIDS programs said they fear the funding may not resume. According to the CDC there are about 100,000 orphans in Myanmar due to AIDS, and testing and treatment programs have allowed hundreds of thousands to access antiretrovirals as well as lower the likelihood of contracting the virus in the first place.

On Tuesday, the Trump administration issued a waiver permitting distribution of HIV medications, but this does not appear to restart broader preventative programs.

In Bangladesh, where more than 1 million Rohingya who fled violence in Myanmar live in chronically underfunded refugee camps, there has been confusion over whether U.S.-funded food programs will continue. Last week, the Bangladesh government said that USAID would continue to provide food aid, but U.S. and U.N. officials appeared unsure where such information originated, according to a report from BenarNews.

The pause has also already impacted a number of exile media newsrooms, which rely on small U.S. grants to provide open information in a country where journalists are routinely imprisoned, forcing a number of them to suspend staffers.

Laos

U.S.-funded programs in Laos range from maternal health to demining operations, a critical need in a country that remains the most heavily bombed in the world, per capita, as a result of U.S. aerial attacks in the 1960s and 70s during the Vietnam War. Less than 10 percent of land in Laos has been cleared of unexploded ordnance, according to Sera Koulabdara, CEO of Legacies of War, which works on education and advocacy around removal of landmines in Southeast Asia.

“It is absolutely essential that we hold ourselves accountable for the devastation we caused,” she said. “Just this month in Laos, a 36-year-old man was killed while simply cooking, an innocent victim of an American war that continues to plague the country.”

A staffer at an agriculture NGO who spoke on the condition of anonymity as he was not authorized to speak to the press told RFA he was doubtful other foreign countries would be able to step in if U.S. funding was pulled.

“After the COVID-19 pandemic, proposing for funding around the globe to support our projects is the biggest challenge — it is very difficult and the amount of the funds is also smaller now,” he said.

The country faces a severe debt crisis that has sent the cost of food and other basic goods skyrocketing. In Houaphan, which is one of the poorest provinces in the country, a school meals program has already had to scale back, according to a teacher who spoke to RFA on the condition of anonymity.

Cambodia

Like Laos, Cambodia still struggles with the legacies of decades of conflict as unexploded ordnance continues to maim and kill. The U.S. halt on funding demining programs is likely to set the government back in its goal to be mine-free by the end of the year.

Heng Ratana, head of the government’s Cambodian Mine Action Center, said the agency receives about $2 million a year from the U.S. government.

As a result of the funding freeze, the center plans to furlough 210 members of its approximately 1,700 workforce nationwide, he told RFA.

“It is a complete shutdown. It is like a forced shutdown,” Heng Ratana said. “We request continued support for the operation because the U.S. funding [agreement] clearly states that it is to clear unexploded ordnance.”

Brian Eyler, the director of the Southeast Asia Program and the Energy, Water and Sustainability Program at the Stimson Center said the funding pause had impacted his own programs, which focus on the Mekong River as well as broader security issues.

He noted that a report launch planned for this week on how the U.S. could counter cybercrime in Southeast Asia had been halted, though he hoped the freeze would soon be lifted.

Nop Vy, executive director of the Cambodian Journalists’ Association, or CamboJa, said 20 to 30 percent of their funding came from USAID, which the group used to run journalist training programs and help fund the independent media outlet, CamboJA News. In recent years, a number of independent media outlets have shut down or been forced by the government to close, leaving a vacuum in access to open information.

Heng Kimhong, executive director of the Cambodian Youth Network, said that the suspension of U.S. government assistance would reduce some of its activities related to youth empowerment and the ability to protect natural resources. A USAID fact sheet issued last year noted that deforestation contributed heavily to climate change in Cambodia, which is considered particularly prone to natural disaster.

Still, Heng Kimhong said he was “optimistic” funding would be restored as the U.S. is “not a country that only thinks about itself,” he said. “The United States is a country that protects and ensures the promotion of maintaining world order, building democracy, as well as building better respect for human rights.”

Tibet

Tibet’s government-in-exile, the Central Tibetan Administration, or CTA, represents the Tibetan diaspora and administers schools, health centers and government services for Tibetan exiles in India and Nepal.

Several sources speaking on the condition of anonymity told RFA that the suspension affects programs run by the CTA, the Tibetan Parliament and a range of Tibet-related non-governmental organizations, raising concerns over the continuity of key welfare programs supporting Tibetans outside of China.

An upcoming preparatory meeting for the Parliament-in-Exile was postponed as a result of the funding pause, sources told RFA.

“The directive applies uniformly to all foreign aid recipients. Since Tibetan aid has been secured through congressional support and approval, efforts are underway to work with the State Department and relevant agencies to expedite the review and approval process for continued assistance,” Namgyal Choedup, the representative of the Office of Tibet in Washington, told RFA.

Various Tibetan NGOs and activist groups based in India expressed their concerns about the impact of the freeze in foreign assistance programs and said they hoped it would be soon lifted.

Gonpo Dhondup, president of the Tibetan Youth Congress, emphasized the importance of U.S. aid for the Tibetan freedom movement and community stability. Tsering Dolma, president of the Tibetan Women’s Association, said assistance has been crucial for maintaining the exile Tibetan community.

“Despite the 90-day suspension, I hope an alternative arrangement can be made to ensure continued U.S. support,” Tashi, a Tibetan resident in Dharamsala, told RFA.

North Korea

While the U.S. has long banned providing aid to the North Korean government, it has been a supporter of North Korean human rights organizations. Such programs help with global advocacy efforts on behalf of those living inside the closed nation, and also support refugees abroad.

A representative from a North Korean human rights organization, who requested anonymity to speak freely, said the group received the stop-work order from their U.S. funders Saturday and requested an exemption waiver.

“We will not be able to pay staff salaries, making furloughs or contract terminations inevitable. Backpay is also impossible because providing backpay would imply that employees worked during that period.”

Ji Chul-ho, a North Korean escapee who is the director of external relations at the South Korea-based rights organization NAUH, told RFA he worried about the longer term impacts of such a pause.

“While this is said to be a temporary suspension of grant expenditures, I worry that it will lead to a reduction in North Korean human rights activities and make it harder for various organizations to raise their voices collectively,” he said.

Sean Kang, co-founder of the Ohio-based North Korea Human Rights Watch, told RFA a funding pause was hugely disruptive.

“U.S. government projects related to North Korea require meticulous planning and scheduling, maintaining security, and being carried out cautiously over the medium to long term,” he said. “A three-month [pause] in such projects can cause significant disruptions, and if funding is ultimately canceled, all the efforts made so far could be wasted, leading to an even greater loss.”

Reporting by RFA Burmese, RFA Khmer, RFA Korean, RFA Lao, and RFA Tibetan.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

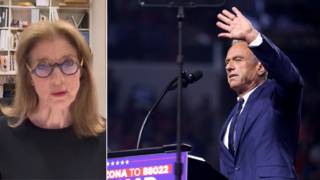

As Senate confirmation hearings begin Wednesday for Robert F. Kennedy Jr., President Trump’s pick to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, his cousin Caroline Kennedy has published a video slamming him as holding “dangerous and willfully misinformed” views on vaccines and other public health issues. Caroline Kennedy is the former U.S. ambassador to Japan and Australia and daughter of President John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s uncle.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Hundreds of millions of people in China and other parts of East Asia are on the move this week to celebrate New Year’s with family gatherings, feasts and traditional activities honoring ancestors and hoping to bring good fortune.

Colloquially known as “Chinese New Year,” the Lunar New Year falls on Jan. 29 this year, but it can come as early as Jan. 21 or as late as Feb. 20. In 2026, the holiday falls on Feb. 17.

The variation is the result of using a lunar calendar based on the phases of the moon, modified into a lunisolar calendar that addresses leap years to keep it roughly in line with the solar year of the Western, or Gregorian, calendar.

Most East Asian nations adopted the Gregorian calendar in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, and the lunisolar calendar is used for cultural events, religious ceremonies, and for some people, birthdays.

Lunar New Year traditions vary greatly among the nine countries or territories covered by Radio Free Asia.

Most of China’s 1.4 billion people -– as well as people in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities around the world, observe the Lunar New Year, known as Chunjie, or Spring Festival.

In China, the holiday brings a two-week vacation and a large mass migration of people back to their hometowns, where extended families reunite for feasts of special dishes believed to bring good luck.

Red envelopes and fireworks

Honoring ancestors is a key part of the festivities, but many of the rituals are forward-looking, symbolizing new beginnings and the hope of good fortune and health in the new year.

Children and youth are given red envelopes full of cash, and families clean their houses and try to pay off their debts to clean the slate. Masses of fireworks are set off to scare away demons that may haunt the new year.

When China was poor, the Spring Festival meant a rare opportunity to eat meat and other quality foods and wear new clothes. Now, many younger Chinese use the break to fly off to Japan to ski or to tour Southeast Asian countries.

The reason “Chinese New Year” is a misnomer is that the holiday is also observed on the same date in South Korea and Vietnam –- two neighbors of China that were heavily influenced by Chinese culture centuries ago. Like China, they will ring in the Year of the Snake on Wednesday.

In South Korea, the holiday is called Seollal and features a return to hometowns, the wearing of traditional hanbok attire, playing folk games, and performing rites and offering food to deceased relatives to honor the family lineage.

Young people bow deeply before their elders and receive gifts and money, and rice cake soup is a main treat for the holiday, which is a three-day affair.

Kim Dynasty and Tet

North Korea, separated from the South in the wake of World War II in a division cemented by the 1950-53 Korean War, returned to the practice of celebrating the Lunar New Year in 1989, and made it an official holiday in 2003.

But the most important holidays in North Korea focus on the birthdates of founder Kim Il Sung and his son Kim Jong Il, the father of current leader Kim Jong Un. Even Lunar New Year is observed mainly by visits to statues of the two elder Kims.

Vietnam, which moved from the lunar calendar to the Gregorian one when it was a colony of France in the late 19th century, calls the holiday Tết Nguyên Đán, or Tết for short. As in China, the Vietnamese will clean their homes and pay off debts, cook special dishes and make offerings to ancestors.

While Vietnam will ring in the Year of the Snake this year, they don’t follow all 12 signs of the Chinese zodiac. When China observes the Year of the Rabbit, Vietnam honors the cat, while the Chinese Year of the Ox is instead the Year of the Buffalo.

Special dumplings and Buddhist chants

Tibet, which was annexed by China in 1950, calls its new year Losar, which falls in February or March, and very occasionally coincides with China’s Lunar New Year. This year, Losar, one of the most important festivals, falls on Feb. 28 and runs for 15 days.

A highly religious holiday, Losar features a special noodle dish called Guthuk, containing dumplings made of different ingredients such as salt or rice that are seen as good omens.

The ceremony Monlam (“Wish Path”) held at major monasteries of the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism entails monks chanting and praying to bring peace and good fortune to their Himalayan region.

The Uyghurs of the Xinjiang region, annexed by China in 1949-50, celebrate Nowruz, the Persian New Year. It falls on or near the Spring Equinox and will be observed on March 20 this year.

The holiday is observed by various ethnic groups in countries along the Silk Road, including Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iran, Iraq, central Asian states and Turkey.

For the Uyghurs, facing repression under Chinese rule and heavy-handed assimilation policies, there is a strong emphasis on preserving cultural identity through gatherings, feasts of special food, music and dance.

RELATED STORIES

Cash-strapped Chinese take the slow train home for Lunar New Year

China swamped with respiratory infections ahead of Lunar New Year travel rush

In song and dance, Uyghurs forced to celebrate Lunar New Year

Splashing water, Buddhist rites

In Southeast Asia, while Vietnam follows the Chinese-inspired calendar and traditions, the traditionally Buddhist nations of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar mark the solar new year in mid-April, when the sun enters the sign of Aries the Ram.

Many rites and practices are similar to those of Thailand, with water festivals aimed at cleansing and renewal, as well as traditional food, games, music and dancing. The festival comes in the hottest month of the year, just after the harvest and before the rainy season.

In Cambodia, the Khmer New Year – known variously as Chaul Chnam Thmey, Moha Sangkran or Sangkran – runs from April 14-16 this year. It is a time of family reunions, religious ceremonies and giving alms to the poor.

In next-door Laos, the New Year is known as Pi Mai or Boun Pimay, and this will run from April 13-16. During the festivities, people splash water on each other to bring good luck and peace throughout the coming year.

The people of Myanmar celebrate the Burmese New Year, called Thingyan, or Water Festival, by throwing buckets of water on each other and on Buddha images as an act of prayer to wash away misfortunes to welcome the new year. It falls on April 13-16 this year.

Edited by Malcolm Foster.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Paul Eckert.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Comprehensive coverage of the day’s news with a focus on war and peace; social, environmental and economic justice.

The post Judge blocks Trump administration freeze on federal grants and loans; LA wildfire victims get aid, ask to keep community needs in mind – January 28, 2025 appeared first on KPFA.

This content originally appeared on KPFA – The Pacifica Evening News, Weekdays and was authored by KPFA.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Human Rights Watch and was authored by Human Rights Watch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A dramatic standoff between the U.S. and Colombia unfolded Sunday with Colombian President Gustavo Petro turning back two U.S. military planes that were carrying deported migrants in shackles, saying immigrants should be treated with dignity. The two countries then traded tariff threats before announcing a deal in which Colombia would begin accepting flights of deported migrants. Meanwhile, Trump has sent 1,500 active-duty troops to the U.S.-Mexico border, further militarizing the region. “We’re very, very concerned,” says immigration activist Fernando García of the El Paso, Texas-based Border Network for Human Rights, whose organization is among those providing resources like Know Your Rights training to immigrants now living under a regime of “anxiety and fear.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Brussels, January 24, 2025–European Union officials and foreign ministers must seize the opportunity provided by the Gaza ceasefire at January 27’s Foreign Affairs Council meeting to ensure that a free press can prevail, the Committee to Protect Journalists said Friday.

CPJ urges the EU to call for independent investigations into the deliberate targeting of journalists during the 15-month war in Gaza, for international journalists to be granted independent access to the territory, and for Israel to reform laws that restrict press freedom.

“The EU cannot continue to turn a blind eye to strong evidence of crimes of international law and the decimation of a generation of Palestinian journalists,” said Tom Gibson, CPJ’s EU representative. “If accountability, justice, and access demands cannot be met, EU leaders must call for a suspension of the EU-Israel Association Agreement.”

The agreement sets out the EU’s legal and institutional framework for political dialogue and economic cooperation with Israel, including respect for human rights as an essential element.

The Israel-Gaza war has taken an unprecedented toll on journalists since October 7, 2023, with at least 167 journalists and media workers killed, overwhelmingly in Gaza. It has been the deadliest period for journalists since CPJ began gathering data in 1992.

According to CPJ’s investigations, at least 11 journalists and two media workers were directly targeted by Israeli forces; the deliberate targeting of civilians is a war crime under international law.

CPJ has documented multiple other abuses in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel, and Lebanon, that require investigation, including assaults, threats, and allegations of torture during the war. Israel was the world’s second-worst jailer of journalists in CPJ’s latest annual prison census, with 43 Palestinian journalists in Israeli custody on December 1, 2024.

At least 10 journalists are being held indefinitely without charge in the West Bank. The EU should join the repeated calls by U.N. special mandate holders for Israel to end this practice, which the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has repeatedly found unlawful.

Throughout the war, Israel has obstructed and punished media coverage and banned international reporters from Gaza, except for on rare trips with the military. Israel must revoke its censorship laws, including one used to ban Al Jazeera and retaliatory directives against domestic media. Israeli, Egyptian, and Palestinian authorities must immediately allow unconditional access for all journalists to enter and operate in Gaza.

The European Union must be true to its values and support these demands.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by Committee to Protect Journalists.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Mexico City, January 24, 2025—Unidentified attackers shot and killed reporter Calletano de Jesús Guerrero while he was in the parking lot of the San Antonio de Padua parish church in Teoloyucan, a town 25 miles north of Mexico City, on Friday, January 17. Guerrero, 57, had been under federal protection since 2014 because of threats relating to his journalism.

“The brutal killing of Calletano de Jesús Guerrero, despite being under the protection of the federal government, underscores the urgency of Mexican authorities’ strengthening its capacity to protect reporters at risk,” said Jan-Albert Hootsen, CPJ’s Mexico representative. “If the state continues to fail in its duty to protect the press, there will be no one left to shine light in the dark and report the news. Impunity in these crimes must end, and authorities must hold the killers to account.”

Guerrero, deputy editor of Facebook-based news outlet Global Mexico, regularly published news stories about crime, violence, and politics in México state.

The Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, a government agency that provides protective measures to journalists, said in a January 18 statement on social media platform X that the most recent threat against Guerrero was on January 13, 2024, when unidentified men threatened him at his residence because of his reporting.

A mechanism official declined to speak via messaging app as they were not authorized to comment publicly on the case.

Police recovered two 9mm bullet casings at the scene of the crime, according to a report by news website Fuerza Informativa Azteca, which added that the police had begun an investigation. Several calls by CPJ to the Estado de México state prosecutor’s office to request comment were unanswered.

Mexico has long been one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists and ranked seventh on CPJ’s 2023 Global Impunity Index, which measures where murderers of journalists are most likely to go free. Mexico has been on the index every year since its inception.

A joint report by CPJ and Amnesty International showed in 2024 that the country consistently fails in its efforts to provide state-sanctioned protection to members of the press.

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As the Trump administration launches what it touts as the largest mass deportation campaign in U.S. history, we look at how immigrant communities and advocates are fighting back. The administration already faces some setbacks, including in its attempt to end birthright citizenship, which a federal judge halted Thursday from going into effect because it was “blatantly unconstitutional.” Thursday’s ruling is the first in what’s expected to be a long legal battle against Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda. “We’re in a moment where there’s a ton of fear in the community,” says Harold Solis, legal director at Make the Road New York, which has filed its own lawsuit against the government. We also speak with Columbia University historian Mae Ngai, who says the fight over birthright citizenship is part of the long history of restrictionist immigration policies in the country. “What we’re seeing this week is shock and awe. It’s meant to terrorize,” she says. “We have to fight on all levels.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Dakar, January 23, 2025—The Committee to Protect Journalists urges Beninese authorities to reverse their January 21 orders suspending six privately owned media outlets — news sites Reporter Médias Monde, Les Pharaons, and Crystal News, the Mme Actu Tiktok account, and Le Patriote and Audace Info newspapers — and to return the press card of Audace Info’s publication director Romuald Alingo.

“Benin’s media regulator must allow these six news outlets to resume publishing and let journalist Romuald Alingo continue with his work,” said Moussa Ngom, CPJ’s Francophone Africa Representative. “Authorities should focus on preserving and expanding freedom of information in Benin and not impose undue restrictions that can have a troubling effect on the entire profession.”

In its order suspending the four “unauthorized websites” Reporter Médias Monde, Les Pharaons, Crystal News, and the Mme Actu TikTok account, the regulatory High Authority for Audiovisual and Communication (HAAC) said that the outlets had been “the subject of numerous complaints” and their content contained “unfounded allegations.” They had also broadcast content without prior authorization from the HAAC in violation of Article 252 of the Information and Communication Code, it said.

In another suspension order, the HAAC cited complaints that Audace Info regularly published “false allegations which discredit the persons concerned and harm their honor and reputation,” and said that Arlingo had failed to respond to the regulator’s summons.

Lastly, Le Patriote was suspended over its publication in December of an exiled politician’s criticism of Beninese President Patrice Talon and a January editorial critical of the army for failing to prevent a border attack in which 28 soldiers died. The HAAC also said the outlet “not only became a bi-weekly without the required formalities, but also appears online,” citing a regulation approving Le Patriote as a weekly paper.

HAAC responded to CPJ’s email requesting comment and copies of the complaints and said the letter would be forwarded “to whom it may concern.” The regulator added, “HAAC’s mission is to protect and promote freedom of expression in accordance with the law.”

This content originally appeared on Committee to Protect Journalists and was authored by CPJ Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

As immigrant communities are bracing for raids and mass deportations promised by Donald Trump, the future for thousands of asylum seekers is also uncertain. As Trump took office, his administration immediately shut down the Biden-era CBP One mobile app, used by Customs and Border Protection to manage asylum requests at ports of entry. Thousands of asylum seekers lost their appointments scheduled for Trump’s first day in office, January 20. “People are afraid. Their lives are uncertain, especially those who have children, those who have fled extreme conditions. Now their lives are once again at risk,” says Guerline Jozef, co-founder and executive director of Haitian Bridge Alliance, who describes how immigrant communities are preparing to resist Trump’s agenda. “We stand ready, committed to push back against the policies that are being created to criminalize people of color and people of immigrant backgrounds.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Read RFA coverage of these topics in Burmese.

A rebel army in northeastern Myanmar has agreed to a ceasefire with the junta after talks mediated by neighboring China, which is keen to see an end to Myanmar’s turbulence, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said.

Myanmar’s junta has suffered unprecedented setbacks at the hands of different insurgent groups over the past year, raising questions about the sustainability of military rule over the ethnically diverse country, where China has considerable economic interests.

China has been putting pressure on some insurgents, particularly those operating in Myanmar regions on the Chinese border, such as the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or MNDAA, to press them into negotiations with the junta that seized power in a 2021 coup.

“With China’s mediation and effort to drive progress … the two sides reached and signed a formal ceasefire agreement, and stopped fighting at 12 a.m. on January 18, 2025,” Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning told a briefing in Beijing on Monday, referring to the MNDAA and the Myanmar military.

The talks were held in China’s southwest city of Kunming, Mao said but she gave no details of the agreement.

“China stands ready to actively promote talks for peace and provide support and help for the peace process in northern Myanmar,” she said.

Neither the MNDAA nor the junta had released any information about a ceasefire at time of publication and Radio Free Asia was not able to contact their spokespeople for comment.

The MNDAA, based in the Kokang region of Myanmar’s Shan state, was one of three allied insurgent groups that launched a stunning offensive in October 2023, pushing the military out of swathes of territory, numerous military camps and towns, despite China’s efforts to broker peace.

The MNDAA captured the major town of Lashio and the army’s regional command headquarters there in early August.

China later closed the border with the MNDAA zone, cutting off vital supplies.

In October, MNDAA leader Peng Daxun traveled to China for medical treatment and to meet a senior Chinese official. Sources close to the MNDAA later told RFA that he was prevented from returning to Myanmar as a way of pressing the group to make peace. China denied that.

RELATED STORIES

Ta’ang rebels renew vow to crush Myanmar’s junta despite earlier ceasefire offer

Myanmar military regime enters year 5 in terminal decline

What happens when China puts boots on the ground in Myanmar?

Questions over Lashio

It was not immediately clear what the ceasefire would mean for Lashio, a major trade gateway with China.

Earlier, the MNDAA said it would agree to a ceasefire if it could retain control of Lashio.

A resident said there had been no major changes there this week.

“Transport is running as usual,” said the resident, who declined to be identified for safety reasons.

“According to what we can see, it doesn’t look like the Kokang Army is withdrawing,” he said, referring to the MNDAA. “I get the sense they have a firm foothold here.”

A political analyst in the region said he had heard that the main issues the two sides discussed in recent talks were border trade and returning prisoners of war, not a rebel withdrawal from Lashio.

He said he did not expect the region’s status to be determined until after the junta holds an election, expected later this year, which it hopes will bolster its legitimacy.

“We’ll have to wait and see if the government and the MNDAA can discuss issues related to territory,” said the analyst, who declined to be identified for safety reasons.

Another analyst, who is also a former army officer, said both sides would initially be cautious.

“The agreement has only just been made … the next thing is to wait and see if each side is committed,” said the second analyst, who also declined to be identified as talking to the media.

The progress towards peace has led to China re-opening some of its border crossings, to the relief of communities deprived of Chinese trade for weeks, sources in the region said.

“Food products can be sent and received normally,” Nyi Yan, a liaison officer with the United Wa State Army, another militia force based in Shan state, told RFA.

“China also eased restrictions on the import of fuel into Wa administrative regions on Sunday night.”

Translated by Kiana Duncan. Edited by RFA Staff.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Burmese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.