Field of Dreams

When I was about seven years old I used to play a “let’s pretend” baseball game in our backyard. I laid out 4 rags I’d gotten from the garage and placed them in a diamond form which represented the bases. The bases were about 20 feet apart. Then I looked at our house and took my batting stance and let my imagination take over. The imaginary scene is no doubt familiar to many of you. It is the last of the 9th inning, we are losing by three runs. The bases are loaded and there are two outs. Then I swing and hit the ball – tsssssch! As Mel Allen was saying in my head “there is a high fly ball deep to right center. The center fielder is at the track. It is going, going, gone”. Then I would trot around the bases. As I got older, I played a great deal of hardball and I hit home runs, but never quite experienced the situation I imagined when I was seven until the end of my playing days.

Coming Through the Hole in the Fence

Around the same time, my father used to take me across the street in the woods to play catch and bat. It was a good scene because the weeds would always stop the ball from going too far. In addition, I always hit with a tree in back of me so that if my father’s pitches were outside the strike zone or I missed or fouled it back, the tree stopped it. Then about a year later my father initiated me into the mysteries of the multiple baseball fields at Jamaica, Queens High School. Officially you had to go through a gate way at the end of the field to get in. But the local kids weren’t having it. They used cutting wires to pry open a hole in the fence. My father and I climbed through the fence and set up. He would pitch to me even though we only had one or two balls. If I hit it past him, he had to get it. But as happens often in these kind of situations, other kids or even adults are around, size up the situation and volunteer to catch or play the field. Willie came by and volunteered to be a catcher. He was an older kid, maybe 14, and looked like he could be a soccer player from South America. If I hit a ball past my father, I would run around those imaginary bases again. My father would retrieve the ball and throw it to Willie to try to get me out at the plate. Willie would make believe he missed the tag or the throw so I could hit a homerun. I was at the age where I couldn’t quite figure out if this was intentional not. Even then, I appreciated his kindness

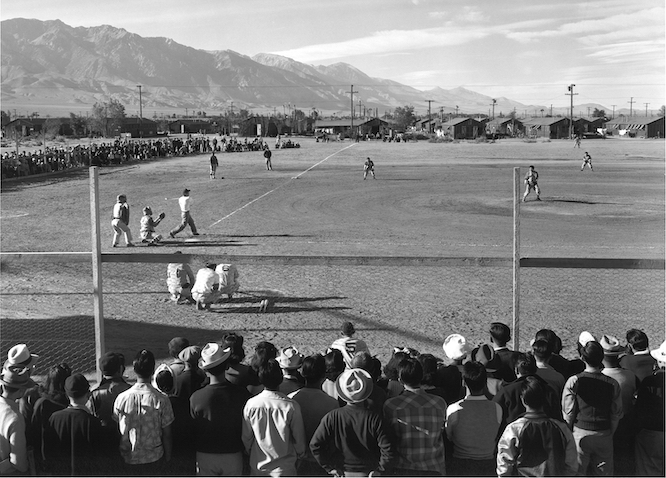

Geographical Constraints of Choose-up Games in the Corner

Our house was only 2 long blocks away from Jamaica High School so I went past the school for many reasons other than baseball. One time I noticed in the distance a group of kids playing baseball in the corner of the park. The actual baseball field for high school games was only part of the park. Surrounding the field was a track and beyond the track was a corner where the kids were playing. The “bases” were old rags of some sort that were laid out maybe 60-70 feet apart (as opposed to the official high school field which was 90 feet apart). These distances were decided long before I began to play. In part it was determined by the fact that our throwing arms weren’t strong enough to make a throw from third base to first, or short to first with the bases 90 feet apart. Also, the pitcher’s mound was only about 45 feet from the plate as opposed to 60 feet for the same reasons.

Adapting to Inadequacies in Numbers and Positions

Our games never had 18 players. Mostly we had maybe 10 or 12. That meant that any kid who wanted to play could. We would adapt our rules to accommodate them. For example, we might decide that right field was in foul territory to shorten the distances to be covered by the outfielders. In addition, we might only have one outfielder to cover center and left. That wasn’t a big deal because most of us were not strong enough to hit it to the outfield. If you hit one on the other side of the high school track it was a home run. In right field there was large tree. As we got older and could hit the ball to the outfield more consistently and the right fielder had to play the ball off the trees. If someone hit a fly ball into the trees and the right fielder could catch the ball bouncing off the trees the batter was out. Needless to say, no one wanted to play right field! The pitcher and the catcher were not specialized positions. The catcher might not even be on the team on defense. It might be a player on the offensive team that was just backing up if the batter missed the ball or it was too far out of the strike zone. While the pitcher was on the defensive team, there were no balls and strikes. The pitcher’s job was to just get the ball over the plate so everyone could hit. There was no standing around. If you struck out it was because you missed the ball on the 3rd strike after either missing or fouling off the first two. Our fields had pebbles and sometimes rocks in the infield. There were many bad hops, but you just took it in stride. In the outfield you had to look out for potholes, mole hills and gravel.

Choosing Up Sides

Choosing up sides was an opportunity to feel proud or humiliated depending on when you were picked. The best players were usually the ones who picked the teams. The better players were chosen first and players with less skill picked later. In those days, Brendan and Owen were two of the best as was Tony Cirillo and I. We could all hit homeruns. Tony and I played shortstop on opposite teams. The shortstop position was usually the best fielder on the team and got the most action. Tony had a great arm. My arm was average but I covered a lot of ground. Brendan and Owen were close friends and always wound up on the same team. I don’t know why. They were both big guys and it might have been the case that we were too afraid to get them on opposite teams. How was it determined who picked first? Well, some neutral player would hold a bat out and grip it tightly. One of the guys who wanted to be captain had three chances to kick the bat out of their hands. If they were successful, they got to pick the first player

Culture and Class

Most of these kids were working class Irish and Italian. Here is a list of the players I remember. Brendan Rice, Owen Brennan, Chris Green, Tony Circillo, James (Head) Circillo, Abe Circillo, Ronnie Christian, Billy Smolin, James Sheehy, Georgie Robles, Bernard Rubino, Evan Munkmeir; Danny Mettines , Billy Insulman, Kenny Lowe, and Frankie Majori. Once in a while a tall lanky guy would slither thorough the hole in the fence on his way to the library. What was odd was that this guy (I think his name was Luke) wanted to be the Pope. As you can imagine, he was mercilessly teased. We’d say “there goes the Pope!”. Our neighborhood was very unusual. Within an area of about a mile and a half we had three social classes represented. From Parson’s boulevard to Jamaica high was a working-class area. The closer you got to 168th Street the houses were lower middle class attached houses. Our block, 168th Street was middle class. I would say there was subliminal tension between us around social class which I will get to later.

What to do About Close Plays

Those adults and kids who were involved in Little League have no idea how easy they had it. The teams had coaches who determined who was going to play what position, and they had umpires who determined who is safe and who is out on close plays. In the sandlots we had to figure this out for ourselves. For us the captains determine the battling order and the positions. But the captain of a team was the first among equals. By a long process of trial and error we learned who was the best in each position so the captain barely had to say a word about who was going to play where. Also, the players themselves got to know who was a weak and a strong hitter and they would self-organize themselves accordingly. No one kept personal records of performances. We just knew what the score was and what inning we were in. To this day I cannot imagine how we kept track of close plays at home, first, second or third base. Our arguments were never technical or legal. They were always matters of who beat the throw and who didn’t. What was interesting as I remember it, is the arguments never lasted very long. We just wanted to keep playing. Our games were usually high scoring so a game was usually never determined by a single call.

The Passing of a Comet: Danny Mettines

My father never liked the kids I played ball with. He grew up very poor. His mother raised seven kids and they were “on the dole”. He was an artist who rose out of poverty to become a commercial artist. We lived in a middle class neighborhood (one square block) and he was afraid my baseball friends would be a bad influence on me. He was always trying to get be to play for church teams as an alternative. I never gave up my friends but I did play on one church team in grammar school. I could never get enough of baseball. At St. Nicholas of Tolentine the teams were organized with the names of native American tribes – The Mohawks, Algonquins, Iroquois, Cheyannes. One day the Mohawks showcased a pitcher who was a real phenom, Danny Mettinis. Danny just towered over us in terms of skill. As a left-handed pitcher he could strike out anybody. As a first baseman he could scoop the ball out of the dirt and do splits to sweep up errant throws from the infield. Danny ran like the wind and as a hitter he could hit the ball 100 feet further than any one else. He wasn’t a big guy but he was built like a tank. He was charismatic, funny and sarcastic. I prayed that he’d never find out about our games in the corner, but that day came.

When Danny came to participate in our games, he revolutionized the existing hierarchy. Brendon, Owen, Tony and I were all knocked off of top ranking. Danny was in a class by himself. Danny was a lefthanded power hitter who would not only hit balls into the trees but over them. He would regularly hit homeruns over the track. It was hard to lose a game if Danny was on your side. Danny was charismatic, funny and sarcastic. You didn’t want to get on his bad side.

For the Love of the Game: Joe Austin

On the actual playing field of Jamaica high, sometimes games and practices would be going on that were not connected to the actual high school baseball team. The players were older, maybe 15-17 years old. The person who was coordinating their practices was an old guy who I eventually came to know as Joe Austin. Joe was an ex-minor league baseball player who worked with kids in the neighborhood and eventually took them into leagues. Joe had skills way beyond any coach I had seen. If you happen to go to a baseball game early and watch the infield and outfield practices, that was the routine Joe would go through with his players. He would provide bats and balls for the players and when they were old enough to go into leagues, he would buy the uniforms. Joe worked at night in a brewery and then five days a week he would take the bus from his house on Sutfin Blvd about a mile to 168th Street. He would then walk 4 blocks to the field carrying bats, balls and gloves in a duffle bag. He was on the field from about 9AM to 3PM. When he went into leagues he named his teams Irish names. Like the Lepricons leprechaun? , Blarney Boys and Shannons.

When Joe thought we were old enough, he started coming to our choose-up games in the corner. He was not pushy at all. He provided bats and balls for us regularly and offered to umpire our games. This was a great relief for us as time wasn’t wasted arguing. He started to make lineup cards for us that he would draw on the back of a paper lunch bag. When we got a little older, maybe 11 or 12, he moved us to another part of the high school park, which had more room. Then he offered to pitch for both sides. This was a boom for us because he got the ball over the plate virtually all the time which speeded up the games. Joe had skills that in retrospect no other coach could ever come close to let alone match. He started to pitch us knuckleballs and curve balls us to get us used to hitting pitches other that weren’t straight. He also worked with kids who seemed to want to become pitchers and he taught them not only to throw curves, but sliders, screwballs, and forkballs. One kid, Joey Fitzgerald made it as far as the Mets farm system. Little did we know Joe was grooming us to be his next team, the Emeralds.

“Yaw wanna play ball, play ball! Ya don’t? Get the fuck off the field”

Joe always welcomed new players so that once we transitioned to a bigger field, more boys came to play. Now the teams each had 9 players on a side. We were bigger, stronger and we could hit the ball further. Younger kids started coming including Jesse Braverman (with whom I’m still friends), Joey Fitzgerald, Bobby Saca, John Brennan, Ritchie Ames. While Joe was very inclusive, he was also very demanding. Once you started playing in the games, Joe expected you to be there every day. Some of the guys I started with stopped coming to the choose-up games probably because they got tired of it. Their skills had leveled off or they got involved in other activities (some activities like drugs or stealing cars). But one player, a catcher by the name of Davey Heckendorn, made a conscious choice to stop playing, told everyone about it and he paid for it.

One day Davey came to the field with someone I had never seen before. I later found out his name was Joe Trapp. Davey started to cry as he announced he wouldn’t be coming anymore. His music teacher told him that if he continued catching, he would ruin his hands by digging the balls out of the dirt. Joe Trapp and David Bernstein were there to support him. As I recall, Joe cursed him out for quitting. If you can imagine what a response was like from a group of 15 predominately Italian or Irish boys hearing this, it wasn’t pretty. We mocked him for crying and I’m sure we threatened Joe and David with a good beating for even daring to come to our turf again. I spoke with him years later, and this is the first topic we discuss. In retrospect, this was one of many miserable things I did as a 12-13 year old.

The lazy hazy days of summer pick-up games with Joe

In spite of the intensity that Joe demanded I would say the two years we spent on the big field were the happiest of all my 13 years of baseball. I loved playing against people I knew and because there were no crowds, uniforms, bells or whistles it was easy to relax. During the course of a summer’s day we would have two games. One in the morning, starting about 9:30 and one after lunch. After the first game I would rush home for lunch, eat quickly and then run back to the field. As I remember it, we let Joe pick the teams instead of us choosing up. Joe had a very good sense of how to pick combinations of players who would make the teams evenly matched. As I recall it most of our games were close. I switched over from shortstop to second base because as the field was larger I couldn’t make the throw from short to first very easily. I started secretly keeping records of my hitting statistics – batting average, homers, RBIs, doubles and triples. Because we were bigger now and could hit the ball further the outfield became more attractive to play rather than a sentence of banishment.

Poetry in motion

One of my favorite activities was having Joe hit fungoes to me in the outfield. He would stand at home plate and I would be stationed in center field. With the wave of his hand, he would motion to me to run from center to right center. He would hit the ball to me perfectly, neither too far to make it uncatchable nor too easy where I would stand still and wait for it. I always had to catch it on the run. Then he would motion me to run to left-center back to right center field and the same thing would happen, back and forth for maybe 30-45 minutes. I loved to fact there was no fence to worry about crashing into. Playing the outfield really developed my arm so by the time I started playing that position I developed a really strong arm. Also, I was a very fast runner but you would never know it with me playing second base. Playing center field, I could utilize my speed to the max. I loved center because, like shortstop, it’s a position where you see the whole field at once.

Joe had nicknames for some of the players. He called me “Lash LaRue” after a movie he had seen where the cowboy used to strip a gunslinger’s gun out of his hand with a whip. Because my arm was pretty wild in center field when it was still developing, my throws home were often way off. He once yelled at me, “hey Lash, the backstop is 18 feet across. Do you think you get that shotgun within that range? I never took it personally. I was flattered that I had enough standing for him to tease me.

Crossing the Rubicon

We did not always just play games among ourselves. Occasionally we would get a challenge from a group from another neighborhood to play a game. The game was not slow pitch. It was with pitchers pretty much throwing fast balls as hard as they could with someone calling balls and strikes. These games were harder for everyone because we had to hit pitches coming at us at much greater velocity. Some of our better players stopped coming. Billy Smolin and Bernard Rubino didn’t return. Tony Circillo stopped being the power hitter he was, but hung on as a pitcher. Brendon Rice was not a good hitter once we switched to fast pitch but continued as a catcher. Chris Green and I made the transition as did Danny.

Our entry into organized leagues as the Emeralds

It was in 1961 when I was 13 that Joe moved us to play on the actual Jamaica High School field. It was around the same year that Joe prepared us to play in the Queens-Nassau League. We stopped playing pick-up games and when we were together it was strictly infield and outfield and batting practice. Joe bought all uniforms. He never made any cuts (telling players they didn’t make the team). I think in our first year we had close to 30 players on our team. I believe it was in 1962 that we had our first team. The league had players that could be up to the age of 17. Our oldest players were 14. Joe wanted to play in a league with older players because the competition would be good for us. In retrospect I think it was a mistake. Before we got into the league, we knew that we were much better than kids our own age. But playing against teams with players who were 2-3 older than we were was demoralizing. I think in the first year in the league we were 4-16. The next year we did better. I think we played about .500 ball. Our last year in the league we thought we could compete for the championship. I think we won more than we lost but we never won anything.

A taste of the East Side kids

Our team was a rough team, kind of like the East Side kids. We got into some fights with the other teams and probably the organizers of the league warned Joe. When we played occasionally in the suburbs we could feel the class tensions and this would carry over to Joe and his relationship with the other players. Joe would coach first base. Sometimes he’d get into razzing with opposing teams’ first baseman. One time

Joe told me to spike the first baseman. I said no. Joe took me out for a pinch runner.

Our team did not have good team spirit. We teased each other almost as much as we teased the other team.

Who’s in and who’s out?

Soon before our first year in the league two players we had never seen before started to come to our practices: Mark Kenny, Ronnie Gerreki. They were not from our neighborhood and naturally enough that challenged the existing pecking order. As I recall Mark Kenney’s father talked to Joe about taking Mark on the team. His father had professional aspirations for Mark and his father knew Joe would develop his talents. I think the same thing happened with Ronnie. Both Mark and Ronnie were very good. Probably the only player we had better than they was Danny. But there was a problem. Mark played short-stop and Ronnie played second. What was going to happen to the existing people we had to play short and second?

There were a number of tension points. One was the fact that Mark and Ronnie did not come up from the ranks. They just appeared, so naturally those who played with Joe for years would feel pushed aside. I was a good hitter and Joe still wanted me in the line-up so he moved me into center field where I had been practicing for a year or two. But we already had a center fielder, Frankie Majori. I was a much better hitter than Frankie and so because of me, Frankie was on the bench. This caused tension between some of Frankie’s friends and I who were also on the team. This was amplified by class conflicts. Frankie, Brendan and Bernard were working class. I was middle class and they knew it because they knew where I lived. I started to feel more isolated than I ever had.

My distance from others on the team was aggravated by the differences in where we went to school. Many of the Emeralds were also playing ball for Jamaica High School, a working class public school. My parents did not want me to go to Jamaica High. It was too rough and they thought I would get a better education at a Catholic school. So instead of going to a high school with my friends which was 2 blocks away, I was shipped off Holy Cross High School, three or four miles away. I was very angry at my parents for this and I had a major rift with my them that never really healed completely. Meanwhile the players who went to Jamaica high noticed my absence and probably concluded that I was spoiled, being shipped off to a private school. After I got home from school in high school, I would walk over to Jamaica High to watch my old friends play, hoping to find some solidarity and imagining I was in center field there. But my old friends rarely acknowledged me. I was an outsider. After a while I stopped going. It was too painful. I never even tried out for the Holy Cross baseball team. I hated going there and didn’t want to spend any extra time there.

My father coming to my games

Despite my father’s disapproval of Joe and the Emeralds, he came to the games. From his point of view it was a natural thing to want to watch your kid play ball. But with rare exceptions, none of the kid’s father’s came to the game, so he stuck out like a sore thumb. In addition, being Italian he would yell when I did something well. It was humiliating. I asked him not to come but he didn’t, telling me that the other kids were jealous because their fathers didn’t come to the game. He didn’t understand that for a 15-year-old teenager living in the United States in the early 1960s, the last thing they wanted was to be seen with their parents. One time we had a Saturday afternoon game in which the field we were supposed to play on was waterlogged by the previous days of rain. I got word that we would switch fields. I called my father to tell him not to come to the waterlogged field and that we were playing somewhere else. He asked me where, and I made believe I couldn’t remember it. Well, I was very happy to know I wouldn’t have to deal with him for a day. However, when I stepped up leading off the game in the new location, Tony Cirillo says to me from the bench, “hey Bruce, guess who’s here?”. It was my father, who must have made some phone calls and found the field.

My performance

I didn’t do nearly as well as I did in the pick-up games. In my three years with the Emeralds I think I hit about .260 or so. I was a streak hitter and better with runners on base. I was a good left-handed drag bunter so Joe translated that as my being a good leadoff batter. I wasn’t. I didn’t like taking pitches and my main goal was to get my cuts in. In retrospect, my best position was batting fifth, after Mark and Danny. That way I could hit with runners on base. The only reason I liked hitting lead-off was I would come to the plate more. Our home field was the 201st Street field which had a short rightfield fence. It was a great experience to hit a ball over the fence and trot around the bases. Until then if I hit one deep over the outfielders I had to run it out as it was it was an inside the park homer. I hit some homers but I also had bad streaks. I once struck out six times in a double-header, four in the first game and two in the second. By the end of the game, Jesse’s brother Roger was pointing out what I was doing wrong in front of a small crowd. He meant well, but it was humiliating.

By my seventeenth birthday my time with the Emeralds was up. I either had to find a new team or stop playing. I had been playing ball for 10 years and wouldn’t know what to do with myself, so I played on. I played three more years, one with the Dukes in South Zone Park; one was with a team in Forest Hills and one with a team from South Jamaica. I will focus most on my crazy year with the Dukes. I learned more about myself and life than I ever dreamed of in all my years with Joe. I had to face my shadow side.

From Joe Austin to Ray Church and the Dukes

The shadow side of my baseball life

In all my years with Joe I was a very good player all around. I could hit for power, I was a very good center fielder, I had a good arm and I was fast. I started every game and finished every game That meant I could count on:

- never being pinch-hit for;

- never pinch-hitting;

- Never being pinch run for

- never pinch running; and

- never going into the outfield for defensive purposes

Doing any of these things was a sign you were not a complete player and only had part-time status. Yet when I played for Ray Church, I had to learn to accept all these roles. But what I found was that as I rose to the occasion and in the process formed at deeper relationship with a coach that I ever dreamed of.

Who was Ray Church?

Ray Church was no Joe Austin. He could not hit fungoes like Joe. He couldn’t curse like Joe and he never played minor league baseball. I later found out the Ray worked at the LaGuardia airport in some administration capacity, he had been in the Air Force, and like Joe, he was single. What Ray had that Joe didn’t have was he was natural psychologist and social psychologist. Ray was very even-tempered and he seemed to have emotional relationships with most of players who were all about 17-18 years old. Ray was about 45 years old. My friend Jesse who used to represent Joe at the league meetings told me that Ray had coached the South Ozone Park Dukes for many years.

My introduction to Ray and Dave Laney

Dave Laney was a well-built, good looking, tall Irish kid with a mass of bleached blond hair and a red face. I never knew whether his face was red because he had been surfing or drinking. I later found out it was both. I played against Davey when I was with Joe. He was a good left-handed pitcher and first baseman with power. One day he showed up at our Jamaica high field to pitch informal battling practice. I didn’t know why he was here, given South Ozone park was about five miles or so from Jamaica. However, Joe remembered him, let him pitch to us and Dave fit right in. I happened to be hitting well in batting practice and remember hitting everything he threw – line drives. I hit one over the wall. The next pitch he just rolled in like he was bowling. “Try to hit that one” he said. We had a good laugh. I liked his spirit. So I asked him about playing for the Dukes. As if he had rehearsed ahead of time he gave me Ray’s phone number. It was only later that I suspected that Ray had sent him over to recruit me. Anyway, two days later I called Ray and asked him if I could play for him. He said “any one of Joe’s boys can play for me”. I asked him when the first practice was and we were off.

From center field to the bench

I got a late start in the Spring of 1968. The snow was slow to dry and so I wasn’t able to work out with Joe as I usually had (his “Spring training” began March 15th). Also I had put on some 10 pound, possibly from drinking in the woods with friends. We had some practices but I was struck by how rudimentary the practices were compared to Joe. However, the players were very good. The Dukes started me in center field but after three games or so I think I only had one hit. Meanwhile a center fielder named Wally Shultz was tearing up his high school league hitting .500. So, by the fourth game Wally was in center and I was on the bench. Ray seemed to understanding how disheartening this way for me. Without too much prodding sitting in his car after a game I blurted out how my father was driving me nuts, trying to control me. Before the next game Ray, came to pick me up along with some other guys and drive us to the field. I invited him to come in and meet my parents, which he did. Soon after he told me how much he understood about my situation of being controlled after meeting my parents.

As the season went on I played some of the time but never constantly. The players were much more supportive of me than anything I had experienced with Joe and all the guys I grew up with. One thing I noticed is that whenever I started a game I was never pinch-hit for, even if I wasn’t doing well. I think Ray understood that would be more painful for me to start and be taken out than not starting at all. Ray had a couple of coaches who were more impatient with me than Ray and I felt Ray was defending me.

One time after another fight with my father, I called Ray and asked him to come get me. He did and we spent a long time talking at his house until about 1 in the morning. I was becoming more and more attached to him and the more I wanted to show him I was a better player than what I had shown so far.

I hit a pinch-triple

That summer I had been working at UPS unloading trucks. I dropped a 50-pound box on my foot so my toe was bandaged for a while. However, I didn’t want to miss our night game we were playing so I went to game. I could still hit but I couldn’t run very fast. In about the 8th inning of a game, Ray told me to pinch hit for a player. The first pitch was a high fastball which I fouled back. I thought to myself I would have creamed that in any other year but this one. Well, lo and behold the pitcher threw me the same pitch. This one didn’t get away from me. I tomahawked to straight away center. It must have been 100 feet over center fielder head. I lumbered around to third with triple. Ray called time out and took me out of the game for a pinch runner. This was so weird. I had never been pinch-run for before. But then again, I probably never pinch hit before starting to play with Ray. After the game I sat in Ray’s car crying. I was so happy I contributed something. We hugged.

A late inning defensive replacement

A little later in the summer when my foot healed and I lost the weight I had gained I found myself still on the bench. In the eighth inning of a game in which we were barely ahead, Ray called on me to replace Al Locaccio, a catcher who was only in left field because we needed his bat in the line-up. I hated left field because there was so little room to run. However, I was in no position to move Walley Shultz out of center. The field we were playing at was Rosedale. This field was notorious for fog. So sure enough, a right hand batter hits a long high drive towards me but curving foul. I keep on running into and through foul territory. I lose the ball in the fog but then it comes out of the fog and I snag it. I must have been 50 into foul territory. Our bench explodes with cheering. Mike Dunn, the other coach who was sympathetic to me looked at Ray in disbelief. Ray taps his forehead with his finger three or four times. I am fighting back the tears.

Ray confides in me he is gay

My relationship with Ray was obviously deepening. He invited me to his place on Friday nights a couple of times just to visit. I asked him questions about himself because I thought it was selfish of me to keep the focus on myself. He told me he wasn’t looking forward to going to his sister’s house on Sunday because they kept asking him when he is going to get married. He then said something to me like, “Bruce, I have to tell you something. I’m gay.” I didn’t have an adverse relation other than sympathy for the situation he was in with his sister. I asked him why he didn’t just tell her. He said he wasn’t ready to do that. It would send shock waves through his family. I understood. I was very pleased that I built up a relationship with him such that he didn’t have to say “don’t tell anyone”. He just knew I wouldn’t. I was proud of that.

Pinch hit double and score the winning run

We were a pretty good team and at the end of the year we were in contention to go to the playoffs. Maybe we were about 12-8. Our game was being played at my old 201st street field where I played with the Emeralds. In our last game which was to determine if we were going to the playoffs or not I came up to pinch hit to start off the bottom of the 9th inning of a game that was tied. Before I stepped to the plate Ray motioned to me to come towards him where he was coaching third base. He looked me straight in the eye and said “look, this is your turf. Act accordingly”. I went back to home plate looked it him. He always gave me a sign to hit line drives, and not to try to hit everything out of the park. I stepped in. The first pitch was a fastball right down the middle. I blasted it over the right field fence and over the Long Island Railroad tracks for a ground rule double (it wasn’t a homer for reasons I won’t go into.). As I look my lead off second, I noticed that instead of pitching from a stretch, the pitcher went into a full wind-up. I broke for third. I got such a great jump I was less that 10 feet from third base when Sandy Ameroso lined a single to right. It reached the right fielder in two hops. I paid no attention to any signals from Ray, I just instinctively thought I could beat the throw. I turned on the jets and slid safely underneath the throw which reached the catcher on a hop. Our dugout exploded from the bench to greet me at home. It was hard for me to cry in front of other boys. They didn’t seem to understand what I was crying about. But coach Mike Dunn and Ray knew what I was crying about.

Our end of the year party

Every year some sandlot baseball teams have a dinner in which the coaches give speeches and awards to the players. I was sitting at a table with one of some of the players I felt closest to. Since I batted .206 for the season, I was confident I wouldn’t be standing up for anything. So along with many other 18-year-old boys at a table, I started to drink. I was never much good at holding my liquor so after 3 beers I was pretty high and the room seemed foggy. Then out of the fog I hear my name. “For sportsmanship award, Bruce Lerro”. What the fuck” I think to myself. I don’t even know what the award is for. The people at my table already started laughing at the prospect of me walking to the front of the room. As I was making my way to the front, Ray, said “and to present him with this award, the only and only, Joe Austin” Now, Joe himself was known to drink a bit and it seemed like he too had been drinking. I got the trophy and wobbled back to my table. the players at my table were fighting off laughing until I was respectfully seated. Then they burst out full flush.

My happy ending with my Forest Hills team

I was done with the South Ozone park Dukes because I was too old. So the next year I hooked up with another team in Forest Hills Queens. I had a very good year with this team. I played center every game and I hit consistently throughout the year. But the climax came at the end of the year when we made the playoffs. This section has been taken from my article Facing the Music: Religion, Nationalism and Sports Have Enchanted the Working Class; Socialism Hasn’t

Making my dreams come true

In 1968 our team from Brooklyn got into a playoff game at Victory Field which was one of the fanciest fields around. My girlfriend, Rose Nuccio, let it be known to me that this was the last time she was coming to my games. Sunday was her only day to sleep in. “Besides” she said, “you are 0-8” (referring to my performance in the last two games.) She brought her sister Miriam along with her for this game. In the top of the first inning, I was up with two guys on base and two outs. The left-handed pitcher, Rick Honeycutt, threw me a high inside curve ball.

“Tshrush”! I tomahawk the pitch and the ball really does head for the right center field fence just like in my fantasy 13 years ago. As I watch the ball head for the fence time and space seem to contract. It’s as if I were in my backyard 13 years ago. The ball lands on the tennis courts on the other side of the fence scattering everyone. I am so out of it that as I make my rounds of the bases, I miss first base. The coach has to get me to touch the base. As I round second, I see Rosie and Miriam jumping up and down screaming like two young Italian gals will. The look on Rosie’s face as our eyes met was like a melting ray of sunlight that united our eyes. I missed third base, too. Finally, as I headed for home most everyone on our team came out to home plate to meet me. It was as if we won the World Series. I disappeared in a mass of teammates at the plate.

A thirteen year life cycle is complete dialectically. I returned to my fantasy of thirteen years ago, on a higher level, deeper, richer more real. I tell this story in my Brainwashing Propaganda and Rhetoric class to point out the Propagandistic power of Sports. There is rarely a dry eye in the house.

The post Choose-Up Games from the Sandlots of Jamaica, Queens NY first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.