This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

“Sumūd, the process of steadfastness, of survivance, is not just a project of survival, but also one of remembrance, record-keeping, and revitalization,” write Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably in the introduction to Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader (Seven Stories Press). The world has now witnessed sumūd at its most tenacious, as Palestinians hold on to life, dignity and a centuries-old culture…

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In his newly published memoir, the Dalai Lama chronicles his 70-year struggle with China to secure a future for the Tibetan people.

In “Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People,” the Dalai Lama shares his experiences since assuming the leadership of Tibet at the age of 16 before he fled into exile in India.

The Tibetan spiritual leader also describes negotiating with a series of Chinese leaders, from Mao Zedong, to his more recent attempts to communicate with President Xi Jinping.

In an excerpt published here with permission from the publisher HarperCollins, the Dalai Lama says China’s government could make Tibetans feel welcome within the People’s Republic of China, but instead communist rule remains that of an “oppressive occupying power.”

He also rejects Chinese involvement in the selection of the next Dalai Lama and says whoever that is “will be born in the free world.”

If Beijing were to look at past history, it would see that policies of repression and forced assimilation do not actually work. It is, in fact, counterproductive, with the main result being the creation of generations deeply resentful of Communist China’s presence on the Tibetan plateau.

If the Chinese leadership truly cares about a stable and harmonious country wherein the Tibetan people could feel at home, its policies need to be grounded in respect for the dignity of Tibetans and to take serious note of their fundamental aspiration to thrive as a people with a distinct language, culture, and religion.

If, in the end, Beijing deems our foundational objective to be incompatible within the framework of the People’s Republic of China, then the issue of Tibet will remain intractable for generations. I have always stated that, in the end, it is the Tibetan people who should decide their own fate. Not the Dalai Lama or, for that matter, the Beijing leadership.

The simple fact is no one likes their home being taken over by uninvited guests with guns. This is nothing but human nature.

I, for one, do not believe it would be so difficult for the Chinese government to make the Tibetans feel welcome and happy within the family of the People’s Republic of China. Like all people, Tibetans would like to be respected, have agency within their own home, and have the freedom to be who they are. The aspirations and the needs of the Tibetan people cannot be met simply through economic development.

At its core, the issue is not about bread and butter. It is about the very survival of Tibetans as a people. Finding a resolution of the Tibetan issue would undoubtedly have great benefits for the People’s Republic of China.

First and foremost, it would confer legitimacy to China’s presence on the Tibetan plateau, essential for the status and stability of the People’s Republic of China as a modern country composed of multiple nationalities willingly joined in a single family.

In the case of Tibet, for instance, it has now been more than seventy years since Communist China’s invasion in 1950. Despite the physical control of the country, through brutal force as well as economic inducements, the Tibetan people’s resentment, persistent resistance in various forms, and moments of significant uprising have never gone away.

Even though generations and economic conditions have changed, very little has changed when it comes to the Tibetan people’s perception and attitude toward those they still view as occupiers. The simple fact is that insofar as the Tibetans on the ground are concerned, the Communist Chinese rule in Tibet remains that of a foreign, unwanted, and oppressive occupying power.

The Tibetan people have lost so much. Their homeland has been forcibly invaded and remains under a suffocating rule. The Tibetan language, culture, and religion are under systematic attack through coercive policies of assimilation. Even the very expression of Tibetanness is increasingly being perceived as a threat “to the unity of the motherland.”

The only leverage the Tibetan people have left is the moral rightness of their cause and the power of truth. The simple fact is Tibet today remains an occupied territory, and it is only the Tibetan people who can confer or deny legitimacy to the presence of China on the Tibetan plateau.

All my life I have advocated for nonviolence. I have done my utmost to restrain the understandable impulses of frustrated Tibetans, both within and outside Tibet.

Especially, ever since our direct conversations after my exile began with Beijing in 1979, I have used all my moral authority and leverage with the Tibetan people, persuading them to seek a realistic solution in the form of a genuine autonomy within the framework of the People’s Republic of China.

I must admit I remain deeply disappointed that Beijing has chosen not to acknowledge this huge accommodation on the part of the Tibetans, and has failed to capitalize on the genuine potential it offered to come to a lasting solution.

At the time of publishing this book, I will be approaching my ninetieth year. If no resolution is found while I am alive, the Tibetan people, especially those inside Tibet, will blame the Chinese leadership and the Communist Party for its failure to reach a settlement with me; many Chinese too, especially Buddhists – some people told me that there are more than two hundred million in mainland China who self-identify as Buddhists – will be disappointed with their government for its failure to solve a problem whose solution has been staring at them for so long.

Given my age, understandably many Tibetans are concerned about what will happen when I am no more. On the political front of our campaign for the freedom of the Tibetan people, we now have a substantial population of Tibetans outside in the free world, so our struggle will go on, no matter what.

Furthermore, as far as the day-to-day leadership of our movement is concerned, we now have both an elected executive in the office of the Sikyong (president of the Central Tibetan Administration) and a well-established Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile.

People have often asked me if there will be a next Dalai Lama.

As early as the 1960s, I have expressed that whether the Dalai Lama institution should continue or not is a matter for the Tibetan people.

So if the Tibetan people feel that the institution has served its purpose and there is now no longer any need for a Dalai Lama, then the institution will cease. In which case, I would be the last Dalai Lama, I have stated. I have also said that if there is continued need, then there will be the Fifteenth Dalai Lama. In particular, in 2011, I convened a gathering of the leaders of all major Tibetan religious traditions, and at the conclusion of this meeting, I issued a formal statement in which I stated that when I turn ninety, I will consult the high lamas of the Tibetan religious traditions as well as the Tibetan public, and if there is a consensus that the Dalai Lama institution should continue, then formal responsibility for the recognition of the Fifteenth Dalai Lama should rest with the Gaden Phodrang Trust (the Office of the Dalai Lama).

The Gaden Phodrang Trust should follow the procedures of search and recognition in accordance with past Tibetan Buddhist tradition, including, especially, consulting the oath-bound Dharma protectors* historically connected with the lineage of the Dalai Lamas, as was followed carefully in my own case. On my part, I stated that I will also leave clear written instructions on this.

For more than a decade now, I have received numerous petitions and letters from a wide spectrum of Tibetan people—senior lamas from the various Tibetan traditions, abbots of monasteries, diaspora Tibetan communities across the world, and many prominent and ordinary Tibetans inside Tibet—as well as Tibetan Buddhist communities from the Himalayan region and Mongolia, uniformly asking me to ensure that the Dalai Lama lineage be continued.

In the official statement I issued in 2011, I also pointed out that it is totally inappropriate for Chinese Communists, who explicitly reject religion, including the idea of past and future lives, to meddle in the system of reincarnation of lamas, let alone that of the Dalai Lama.

Such meddling, I pointed out, contradicts their own political ideology and only reveals their double standards. Elsewhere, half joking, I have remarked that before Communist China gets involved in the business of recognizing the reincarnation of lamas, including the Dalai Lama, it should first recognize the reincarnations of its past leaders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping!

In summing up my thoughts on the question of the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama in that 2011 official statement, I urged that unless the recognition of the next Dalai Lama is done through traditional Tibetan Buddhist methods, no acceptance should be given by the Tibetan people and Tibetan Buddhists across the world to a candidate chosen for political ends by anyone, including those in the People’s Republic of China.

Now, since the purpose of a reincarnation is to carry on the work of the predecessor, the new Dalai Lama will be born in the free world so that the traditional mission of the Dalai Lama — that is, to be the voice for universal compassion, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, and the symbol of Tibet embodying the aspirations of the Tibetan people — will continue.

Copyright @ 2025 by the Dalai Lama. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by RFA Tibetan.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! Audio and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Laura Flanders & Friends and was authored by Laura Flanders & Friends.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

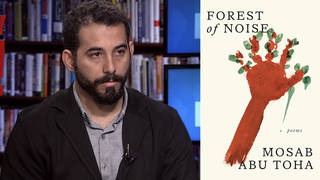

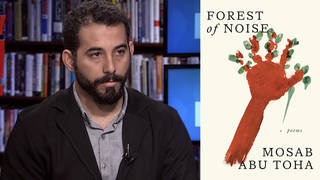

In this special broadcast, we begin with an extended interview with Palestinian poet and author Mosab Abu Toha about the situation in Gaza and his new book of poetry titled Forest of Noise. He fled Gaza in December after being detained by the Israeli military, but many of his extended family members were unable to escape. He reads a selection of poems from Forest of Noise, while sharing the stories of friends and family still struggling to survive in Gaza, as well as those he has lost, including the late poet Refaat Alareer. He also describes his experiences in Gaza in the first months of the war, including being displaced from his home and abducted by the Israeli military, noting that the neighborhood in Jabaliya refugee camp that his family first evacuated to last year was bombed by the Israeli military just days ago. “Sometimes I want to stop writing because I’m repeating the same words, even though the situation is worse. The language is helpless,” Abu Toha says. “Why does the world make us feel helpless?”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In this conversation, Professor Clare Wright, Professor of History and Public Engagement at La Trobe University, talks to me (BroadAgenda editor, Ginger Gorman), about her new book, Ṉäku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions. We explore the profound historical and cultural significance of these petitions, as well as Professor Wright’s personal connection to the Yolŋu people and their enduring struggle for land rights and recognition.

Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions are a set of four documents or artefacts or artworks (they’ve been called all these things) that were sent by the Yolŋu people of northeast Arnhem Land to four Australian parliamentarians (Prime Minister Robert Menzies, Opposition leader Arthur Calwell and Labor MPs Kim Beazley Snr and Gordon Bryant) in July 1963 to protest against the incursion of mining interests on their lands.

The petitions, which made eight requests, were typed in two languages – Yolŋu matha and English – then pasted on to bark frames on which the traditional designs, animals, plants and ancestral beings were painted in ochre to represent the clan lands and creation stories of the Miwatj region. The petitions were signed by 9 men and 3 women who had been carefully selected by the Yolŋu elders to represent the various Yolŋu clans.

Two of the petitions were presented to the House of Representatives, the first on 14 August 1963, the second – after the initial one was rejected by Minister for Territories Paul Hasluck – was presented and accepted on 28 August. It’s important to recognise that the petitions did not protest against mining in the region per se. What they called for was consultation on any decisions that were made about who could come on to their lands and how their lands were to be used as well as compensation for any resources taken from those lands. These requests accorded to Yolŋu law. Spoiler alert, but suffice to say those requests went unheeded.

The story of Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions has been important to the Yolŋu descendants of those elders who struggled for their human and land rights. It’s a story that many of today’s leaders and elders, including the strong women, wanted to have told.

They wanted their old people remembered by the rest of Australia. My family had the unique privilege of living with the Gumatj clan in northeast Arnhem Land in 2010. Gumatj leader Dr G Yunupiŋu was particularly keen to have the story told.

(He had been 15 years old in 1963 and his father Mungurruway was one of the leaders of the protest action.) I was adopted into the Yolŋu kinship by Dr Yunupiŋu’s fourth wife, Valerie Ganambarr. I was given the Yolŋu yaku (name) Guymululu, meaning ‘special tree’. I became close to many powerful, commanding Yolŋu women. It was from within this inner circle of family and community that I was effectively tasked with writing the history of Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions, from the perspective of both its white and Yolŋu protagonists, male and female.

Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions were the first petitions put to the federal Parliament in an Australian language. They were also the first petitions presented to the federal Parliament to lead directly to a parliamentary enquiry. They are also the first petitions by Indigenous Australians to assert land rights, and as such are the direct precursor to subsequent land rights legislation as well as the paradigm-shifting native title rulings in Mabo. These factors alone make the petitions important documents in the history of the nation.

But more than just setting those procedural precedents, Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions can be seen as an attempt by the Yolŋu people to come to a form of diplomatic agreement-making between one sovereign nation and another. In 1963, the Yolŋu people believed themselves to be nothing but the owners of their lands, acting under their own governance structures, economic autonomy and legal regimes.

In other words, their sovereignty had never been ceded.

Widening the frame, we can also see Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions as a pivotal event in the history of Australian democracy, sitting alongside the Eureka rebellion (1854, workers’ rights, Eureka Flag) and the women’s suffrage movement (1902, womens’ rights, Women’s Suffrage Banner).

That’s why this book is the third instalment of my Democracy Trilogy. The trilogy turns on the material heritage of Australian democracy – flag, banner, bark – but also demonstrates that each moment was about disenfranchised people demanding the right to be heard, to be counted. Each of these moments/movements was about Voice.

Cover of Naku Dharuk: The Bark Petitions. Picture: Supplied

The Yolŋu people had no reason to expect their requests for recognition of their political sovereignty and land rights would not be respected. They had been trading and agreement-making with ‘outsiders’ for centuries, strangers who abided by Yolŋu laws. Their confidence was only truly scorched by losing the Gove Land Rights case which followed on from Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions.

I started researching and writing this book over a decade ago. The Uluru Statement from the Heart and the Voice referendum were not, therefore, political agendas that were anywhere near my consciousness. I had no barrow to push, just an incredible, unforgettable (yet largely forgotten) story to tell. As the political and social dimensions of those movements played out from 2020, it became clear to me how many similarities there were between the 1963 Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions campaign and the present-day struggles for the right to be heard, the right to meaningful consultation and consent.

Indeed the referendum for a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament was held in the 60th anniversary year of Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions. It is heart-breaking that the majority of Australians – including the Coalition parties – are still not prepared to listen to what our First Australians want to say about their everyday needs as well as their historical and contemporary experiences, inspirations and ambitions.

This was easy: I wrote from the archives up. The bad actors in this story made themselves pretty well known to me from the primary sources long before Dr G Yunupiŋu identified them by name to me!

I think my narrative style is perhaps only unique to scholarly history writing. My literary influences are drawn far more from fiction of screen writing than academic discourse. First, I write narrative non-fiction: the beats are story-driven, not argument-driven. I also focus on character and write on the heels of the very many characters who contributed to the story of Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions; if they don’t know what’s going to happen next as protagonists, neither do we as readers.

I think this approach is more reflective of the way that people live their lives, people then and people now. I hope it shows that people (ie: us) make history every day in the choices they make, the alliances they form, the values they honour, the rights and liberties they struggle for, the way they act as either ‘enlargers’ or ‘punishers’, to borrow from Manning Clark.

I think that it’s also important to amplify the symphonic nature of the past. There were/are a lot of voices, trying to communicate their hopes, aspirations, grievances and principles. Drawing only from the colonial/national archive tends to lower the volume on this polyglot, polyvocal past. Finally, in Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions I have also tried to insert the imperatives of Yolŋu history-making and storytelling, which tend to embrace temporalities that loop and spiral and return rather than only western enlightenment ideas of time and space, which tend to follow chronological, teleological ideas of progress: beginning, middle, end.

Professor Wright spent thousands of hours working with Yolngu Elders while she wrote and researched her book. Picture: Supplied

It was a huge turning point in my thinking, years into the research for this book, when I thought to ask Dr G’s what the Bark Petitions were called in Yolŋu Matha. It had never occurred to me before that the Yolŋu would have their own language. His answer took some time to fully digest: Ṉäku Dhäruk. Ṉäku, meaning ‘bark’, for the material that is used for bark painting. And Dhäruk, meaning ‘the word’ or a ‘message’ or a meeting out of which a collective message or outcome will be decided.

There was no sense of a ‘petition’ at all. We understand petitioning as a means by which a subservient people requests something a higher power. ‘Your servants humble pray’ is part of the desiterata of the Westminster petition. But the Yolŋu had no such hierarchies in mind. They saw themselves as equals, on the same level, negotiating across, not begging up. Understanding Ṉäku Dhäruk/the Bark Petitions as gifts of diplomacy changes the whole power dynamic of the situation. And gives us hope, I think, that such anti-colonial relationships of political equality might exist between First Australians and settler Australians again.

The post The Yirrkala Bark Petitions: A story of sovereignty and resistance appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

In an extended interview, Palestinian poet and author Mosab Abu Toha discusses the situation in Gaza and his new book of poetry titled Forest of Noise. He fled Gaza in December after being detained by the Israeli military, but many of his extended family members were unable to escape. He reads a selection of poems from Forest of Noise, while sharing the stories of friends and family still struggling to survive in Gaza, as well as those he has lost, including the late poet Refaat Alareer. He also describes his experiences in Gaza in the first months of the war, including being displaced from his home and abducted by the Israeli military, noting that the neighborhood in Jabaliya refugee camp that his family first evacuated to last year was bombed by the Israeli military just days ago. “Sometimes I want to stop writing because I’m repeating the same words, even though the situation is worse. The language is helpless,” Abu Toha says. “Why does the world make us feel helpless?”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! Audio and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

When I wrote about cyberhate in my book Troll Hunting (2019), I wanted people to understand two important points. First, that trolls are rarely those stereotypical lonely guys, spitting out vitriol alone in their mothers’ basements. They’re more likely to be white-collar, professional types, working strategically in groups to silence or harm their victims, or drive them to self-harm. Second, that cyberhate doesn’t exist in some online bubble. Often it spills over into the “real world”, resulting in stalking, physical harm, and even terrorism. These insights were vital to convince governments and authorities that trolling has ‘real world’ consequences, has to be taken seriously and properly regulated.

Last month, when I attended a discussion between Australia’s Van Badham and Nina Jankowicz, an American disinformation expert, I was intrigued to learn that those who spread disinformation on the internet work similarly to trolls. The conversation was expertly hosted by politician, lawyer and author, Andrew Leigh as part of the Australian National University’s Meet the Author series.

Listen to the whole conversation here via the link above.

Both Nina and Van agreed it is imperative governments, authorities and the general public understand what is happening because this online “info war” is nothing less than an ideological war against democracy, undertaken by groups and with real world consequences.

Nina and Van’s discussion focused on the rise and impact of conspiracy theories and disinformation. Nina Jankowicz, author of How to Lose the Information War and How to Be a Woman Online, has worked as an adviser on disinformation for both the Ukrainian and American governments. Van Badham is a well-known Australian activist and writer whose book, QAnon and On exposed the conspiracy theories spread by a group which convinced thousands, possibly millions of people, that our governments have been compromised by a global cabal of paedophiles.

Van explained that conspiracy theories are the tools used to build communities and mobilize people, both online and in real life.

Van took a moment to explain the difference between “misinformation” and “disinformation”. Misinformation involves untruths spread by those who genuinely believe the veracity of what they’re posting – repeated without malign intent. Conversely, the aim of disinformation campaigns is to mobilize people towards believing things that are not true, and to act on claims that are not true.

Nina made it clear that disinformation campaigns are being waged with the clear intent to exploit fissures in society as a means of destabilizing democratically elected governments. Van added that what may appear to be “grassroots” movements are actually communities being assembled, “stoked, encouraged and provoked by organized pro-disinformation operations” aligned with the interests of authoritarian governments.

In Australia last year, both speakers were horrified to see the disinformation campaign built around The Voice referendum. Watching the public debate, Van saw precise targeting by sponsored groups like Advance Australia around a “No” case “absolutely saturated with disinformation.”

Van explained that the aim of the Voice disinformation campaign was to create uncertainty and confusion – noise – so that Australians would feel less confident about voting “Yes”. Those with a vested interest in derailing the Indigenous Voice to Parliament used a strategy famously described by Trumpist, Steve Bannon, as “flooding the zone with shit.”

Watching this all play out, Van thought to herself, “Oh my God! It’s here. It’s come to Australia!”

Now, she is seeing the same strategy being used in the debate about nuclear power stations in Australia.

Both Nina and Van agreed that artificial intelligence technology is increasingly being used to build sophisticated disinformation campaigns designed to mislead, confuse and agitate the public. The rise of AI has “turbo-charged” disinformation campaigns. For example, Nina said that tools like Chat-GPT have made it easier for Russian disinformation to appear as if it’s written by native English speakers.

Andrew Leigh, left, Nina Jankowicz, centre, and Van Badham, right, speaking in Canberra about disinformation. Picture: Ginger Gorman

In this country, Van has been tracking the debate over nuclear power stations and discovered “quite discernible patterns of AI generated content that is targeting susceptible groups within the electorate to soften them on the issue of nuclear messaging.”

Importantly, a more permissive social media environment, particularly on X (formerly Twitter) under the leadership of Elon Musk has made it easier for fake personas and disinformation to proliferate.

Democracies rely on public debate – it’s the way we decide what policies will most benefit our families, and society as a whole. This influences the way we vote. It’s perfectly reasonable for people to hold different views. But, when the well of information from which those views are formed is purposefully poisoned by foreign interests, the result is the kind of culture wars we now see driving a massive wedge in American society. Into this wedge step charismatic, authoritarian leaders who serve particular vested interests with voting blocs they have built through online disinformation campaigns.

Van explained that one of the reasons she and Nina were touring the country was to raise consciousness about the “clear and present” dangers of disinformation to Australian democracy.

Van warned we are all vulnerable to disinformation. She said, “I’ve been lured into disinformation. It’s not something to be ashamed of.” It’s easy to be manipulated especially when Australia’s online environment is largely unregulated.

She said, “I had the horror of my life seeing someone who I would have formerly considered a friend, sharing material that I knew was being produced by a Russian disinformation account.”

Both Nina and Van acknowledged that speaking out against these bad actors is likely to result in a torrent of online abuse that may well spill into the real world. The aim is to frighten and silence opponents.

Despite death threats, both have persisted, but they warn women, in particular, to learn and practice cyber-security measures and to step away from the computer or phone for a while if what’s happening online is affecting your mental health.

Regulation of fake accounts and disinformation by platforms such as X and Facebook is desirable, but there is considerable pushback because dissent and chaos drives “clicks”, and “clicks” drive profits. Raising consciousness about disinformation campaigns amongst friends and family is something we can all do to combat this assault on our democracy.

Working to heal the fissures – the open wounds which leave our societies vulnerable to attack – is another priority. Fact-check before you share information online. And all of us can exercise our democratic rights by contacting our local MP, demand they take the spread of disinformation seriously and pass legislation to control it. Recommend, perhaps, that they read Van Badham’s and Nina Jankowicz’s books – or send them a copy.

The post The gutsy women fighting global disinformation online appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

Read this interview in Mandarin.

At the far end of a quiet garden courtyard in Chiang Mai, home to a small “village” of exiled Chinese writers and intellectuals, is a communal study room with books lining the walls.

Veteran investigative journalist Dai Qing, 83, once one of the Chinese Communist Party’s most influential critics, is often there, reading and writing as she enjoys a quiet life of contemplation in Thailand — as well as working on her forthcoming book, “Notes on History.”

Dai, a former reporter for the party’s Guangming Daily, was an early and prominent critic of China’s flagship Three Gorges Dam project, publishing a book Yangtze! Yangtze! arguing against the move.

She also served time in Beijing’s notorious Qincheng Prison for supporting the students during the 1989 pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square.

Now part of a community of exiled Chinese writers and researchers in the northern Thai resort town, Dai spoke to RFA Mandarin — after her daily swim — about what led her there:

RFA: Why Chiang Mai?

Dai Qing: I should say that Chiang Mai wasn’t actually my choice. I’ve always lived in big cities, ever since I was a child. When they asked me where I was from, I said I was Chinese. For example, I was born in the wartime capital Chongqing, and later I worked in a Beijing high school. I have always been in big cities. I really don’t like big cities, I don’t like the bustle and prosperity — I like the quiet: trees and grass, blue sky and white clouds.

When we set up this courtyard, it was as a small community of friends. We all shared the same values and common hobbies, like reading. We set up a research center and invited people from foreign universities with an interest in China to come. We have so many people here who can talk to them, share our experiences, and they can stay here too.

RFA: How many homes are here?

Dai Qing: Today, there are 31 houses that were designed by [independent writer] Ye Fu. Many of the people here are his friends, and they just sort of came here. It costs less than one-fifth of the price of a place in Beijing, right? But they don’t all live here. Some are rented out. Who do they rent to? That’s another question. People who are dissatisfied with the Chinese education system, who want to bring their children here to study and enroll in the British education system. We rent houses to them. There are several families like that. You can see that the most lively ones are full of kids.

RFA: Did they come before or after the COVID years?

Dai Qing: Some came before and some came after, so there are basically two groups. The first group is people who are dissatisfied with China’s education system and come here to have their children attend school. The second group is Ye Fu, Tang Yun, and Wang Ji, all people who have suffered political discrimination and oppression in China and can’t go back.

RFA: So you came here because you were dissatisfied with Chinese politics?

Dai Qing: It’s not that simple. It’s just that … before Hu Yaobang’s death in 1989, civil society in China hadn’t achieved a modern transformation, but it was actually much more relaxed than it is now. We could do a lot of things. Then Hu Yaobang died, and 58 days later, the crackdown continued, until it became what it is today.

RFA: What happened to you in 1989?

Dai Qing: Well, I was a journalist, so of course I was in contact with people from all walks of life. I told [1989 student leader] Chai Ling, do you think that just because you’re a good student of Chairman Mao that you can gather a bunch of heroes just by raising your arms, and be a leader? That’s not how things are. I kept telling them that they kept resisting and calling for democracy and demanding concessions even though the leaders had already made concessions. I told them it wasn’t right. I was trying to bring about peace, and they wound up putting me in Qincheng.

RFA: When you left China, did the police warn you not to give interviews, or make other demands?

Dai Qing: The police actually let me leave in 2023 because I had so many friends and relatives in the United States, and I wanted to go visit them now that my daughter had retired. She retired on her 55th birthday in 2023. I felt that I was in the later stages of my life, and I made an agreement with them that I wouldn’t give interviews or take part in activism, and they let me leave.

Then, when I went to various universities, everyone wanted to talk to me, but it had to be in closed-door meetings. Participants weren’t allowed to record audio or take photos or video with their phones. No one was allowed to publicize it. When I got back to Hong Kong and then to Beijing, the police were very happy. As far as they were concerned, I’d stuck to the deal.

Later I asked … their boss who came to visit me whether he knew what I’d done back in the 1980s. He said they hadn’t bothered to research it. But they know now.

RFA: How are you getting along here in Chiang Mai?

Dai Qing: Actually it’s a question of “three noes and two don’ts” – that’s the way I describe my situation right now. I have no pension, no social security and no medical insurance, which is the “three noes” part. The “two don’ts” are: don’t get sick, and don’t hire help. I do all of the housework myself.

RFA: Do you still follow what’s going on back in China, culturally, economically and politically?

Dai Qing: Not so much. I care in the sense that I want to know what’s going on. For example, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee was delayed for so long, then it sent out a message about how the private economy and the state-owned economy will be handled. I stay abreast of these things, but I won’t be there on the front line any more, pointing out issues and criticizing the government. Not any more. There are a lot of young people who are doing that now. I just plan to stick to what I can do, and take it easy in the time I have left.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Qian Lang for RFA Mandarin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Historian and journalist Betsy Phillips discusses her new book, Dynamite Nashville: Unmasking the FBI, the KKK, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control, which chronicles three bombings in 1957, 1958 and 1960 aimed at supporters of the civil rights movement in Nashville. The book has sparked a reopening of the formerly cold cases, the likely perpetrators of which Phillips names in her book. Phillips details what she uncovered through her research about the connections between the white supremacist terror campaign of the previous century and ongoing neo-Nazi activity in Nashville and the U.S. today.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

A celebrity decorator with blue hair. A single mother who advised JFK in the Oval Office. A Christian nudist with a passion for almond milk. A century ago, ten Australian women did something remarkable. Throwing convention to the wind, they headed across the Pacific to make their fortune. Historian Dr Yves Rees tells their story in a new book called: Travelling to Tomorrow – The modern women who sparked Australia’s romance with America.

In 2008, back when millennials were still young and skinny jeans were fashionable, I was procrastinating in the Melbourne Uni library when I stumbled upon an article that changed my life. On the pages of an old magazine, I discovered the story of modernist artist Mary Cecil Allen. An enfant terrible of the Melbourne art world, in 1927 Mary decamped for the brighter lights of New York, and later introduced abstract expressionism to Australia. Sounds like a good research project, I thought. I was twenty and had just stepped onto a trajectory that would shape the next sixteen years.

Once immersed in Mary’s life and times, I started wondering if there was a bigger story here.

New York was a daring choice for an Australian in 1927—let alone a young and unaccompanied Australian woman. Had any other women done such an audacious thing? Turns out, they had. Hundreds and hundreds of them.

Writers and musicians and economists and actors and librarians and more. Over four years, I did a PhD on the Australian women who, in the early 1900s, set sail to seek their fortune in the United States.

Back then, I still thought I was a woman too. Why wouldn’t I? I’d been born with a vagina, and so everyone concluded: girl. I was a people pleaser, a perfectionist, and I was determined to ace this gender assignment. In 2012, when I started my PhD, I had long hair and short skirts and twenty-four years of female socialisation that kept me making nice.

As a novice women’s historian, I approached my subjects from a position of identification. Like them, I was a white Australian with the privilege and appetite to orient my life around travel and education and career. They felt, in many ways, like a version of me born a century earlier. They were my forebears, direct ancestors in a lineage of feminine resistance to being put in small boxes, women who could model how to navigate womanhood in a world that still positioned men as the default human subject. Through them, I might finally learn how to be.

Over my long years of research, I ran towards these forebears like an orphaned puppy looking for a mother, a hot mess of confusion and gaping need. How do I do this strange thing called womanhood? If I study you hard enough, if I join all the dots of your big and rebellious lives, will I finally crack the code? Teach me, show me the way. Solve my gender trouble, oh ye fellow white ladies who went before.

You can probably guess how this story ends. Spoiler alert: when womanhood feels like a puzzle with a missing rulebook, or a role you never signed up to play, or a scratchy jumper a few sizes too small, you might not actually be a woman at all.

It took me until 2018 to figure this out. By that point, I was thirty and revising my PhD into a book. I had a publishing contract, an academic job. The whole shebang. I was a real women’s historian. Only I wasn’t, and never had been, a woman myself.

Cover image: Travelling to Tomorrow

Once this realisation landed, I didn’t know how to think about women in the past. Were they still my forebears? Was their history still my history? Women’s history was my inheritance, or so I thought. Now, however, I’d been disinherited—or had disinherited myself. It was too painful to consider, so I didn’t.

Instead of revising the manuscript, I invented other work for myself. For years, I wrote economic history, migration history—anything to avoid my ‘women’s history’ book, that rotting corpse of my old certainties. I didn’t know how to write women’s history anymore because I no longer understood my relationship to that concept. My book remained in the form of Word drafts and manila folders, collecting dust.

Then one day, I remembered that Mary Cecil Allen played fast and loose with her own gender assignment. The painter preferred pants and came to be known by her masculine middle name. If a Cecil in pants was part of ‘women’s history’, was this field really so far removed from my own experience?

Would someone like Mary have understood themselves as nonbinary if they’d had this concept at their disposal? The possibilities of self-definition are always shaped by historical context. With different ideas and words floating around, the same person might think about themselves in an entirely new light.

I had already met countless older people who told me, somewhat wistfully, that they would call themselves nonbinary or trans if only they were 30 or 40 years younger. Had they’d encountered this idea in their youth, their lives might have looked very different. How many other people, dead and buried, might have thought the same way?

When I started looking for it, gender non-conformity was everywhere in my ‘women’s’ history. There was the nurse Cynthia Reed, who was known by the nickname Bob and had surgery to reduce her breasts. Then there was the author Dorothy Cottrell, who wrote an autobiographical novel with a male protagonist. In that same novel, another character is described as having a mix of male and female energies – a gender expression we’d now call nonbinary. ‘In some natures sex is definitely marked in every fibre of being’, Dorothy wrote. ‘But in rarer cases the blending of the elements masculine and feminine seem almost equal.’

This is not to say that these ‘women’ were not women at all. It is not to say that every person in history who challenged gender norms was nonbinary or trans. It is simply to say that we know less than we think. We can know the gender people were assigned at birth, we can glimpse whether they accepted or challenged that assignment, but beyond that is a whole realm of unknowability and mystery. We can only wonder and imagine.

How marvellous, how beautiful.

Picture at top: Yves Rees. Picture: Catherine Black

The post Finding my way back to women’s history appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

In this Q&A, Catherine Fox discusses her new book, Breaking the Boss Bias, with BroadAgenda editor, Ginger Gorman. Fox highlights the urgent need for gender equity in leadership. She addresses the stagnation of women in power roles and the systemic barriers they face, while emphasising the importance of diverse leadership styles. She offers hope and insight into how we can work together to create a more equitable future.

I was alarmed to see the fragile progress made towards better gender equity actually plateauing or going backwards particularly in critical decision making roles. There is still only a handful of women running governments worldwide, in powerful CEO jobs, and they are lucky to make up 30% of senior ranks.

Even though there are more women in Australia’s federal parliament and in cabinet, men are over-represented in many influential roles across party lines and in the bureaucracy. The Global Economic Forum tracks leadership progress which has increased about 1% a year until last year when it went backwards. Yet instead of taking this seriously many signs suggest organisations are taking their eye off the ball or lapsing into complacency.

It does matter. Aside from being fundamentally unfair to marginalise half the population of a well-educated country from power jobs, the evidence shows it makes a difference to outcomes for all women.

When women run governments there’s usually more chance of gender legislation getting passed (I interviewed UTS law academic Ramona Vijeyarasa about this which was the focus of her book, (The Woman President: Leadership, Law and Legacy for Women’), the gender pay gap narrows and more women progress.

Not to mention that when there are more women on decision making bodies (not just one but two or more) the nature and scope of the discussion changes and so do the priorities. It’s not because women wave a magic wand or are ‘better’ than men. But they bring different experience and focus to the table, they are role models and their presence encourages more efforts to close the gap. Many also realise they have a vested interest in seeing things change.

Power systems are very good at recycling themselves and so the cohort in charge has minimised the problem, or pointed to examples of women in top jobs as proof there is plenty of momentum underway. This is often accompanied by gender washing – painting a much rosier picture than the reality particularly with tokenism like celebrations of International Women’s Day.

This over-optimistic and compliance driven messaging has been disturbingly successful – not just in organisations but across society (nearly 60% of Australians think we are near or already have gender equity according to 2023 Gender Compass research). It’s supported by claiming workplaces are meritocracies, pointing to limited examples of change, misleading statistics (‘half our employees are women’) and corporate value statements as credentials.

But this is becoming increasingly risky. Some of Australia’s largest employers had significant gender pay gaps which were published for the first time earlier this year. The data showed that despite the rhetoric, men dominated higher paid senior jobs from banks to retailers and supermarkets. Far from solving the problem, there’s been lots of convenient denial and very little effective action.

There’s a lot of glass cliffs about – I think Qantas may be an example with constant pressure on Vanessa Hudson to turn around the damage done to the brand in very difficult circumstances. QU academic Alex Haslam, who was one of the original glass cliff researchers (with Michelle Ryan, now the head of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at ANU) described the dynamic as a line of potential male candidates looking at the mess they would be inheriting and all taking a step back leaving the only woman contender in the hot seat – a last resort choice.

Happens in politics often – former PMs Julia Gillard and Theresa May are examples. Stereotypes about women being good at tidying up a mess and settling things down also tend to play into this dynamic. When women then struggle in these tricky situations they also get less time to prove themselves – women CEOs have a much shorter tenure on average than men.

Author Catherine Fox says she “…was alarmed to see the fragile progress made towards better gender equity actually plateauing or going backwards.” Picture: Shurtterstock

Many workplaces reward employees who can work set hours over continuous years without breaks and accrue experience to then progress. This clearly penalises care givers who are mostly women and this burden hasn’t shifted much, while caring carries a stigma too. Men who take parenting leave are also now finding they are judged as less serious workers and less likely to progress.

Most of the accepted leadership models have a masculine skills held up as models are overtly masculine, inaccessible and expensive childcare is a massive deterrent to women’s workforce participation and hours, while superannuation is still structured around a primary earner with unbroken tenure.

On top of this set of issues, women from further marginalised groups – racially diverse, LGBTQ+, disabled – are facing a double whammy and are far less likely to get the same opportunities as other women or men. We don’t have

Backlash about the ‘unfairness’ of programs supporting women means there’s more reliance on stereotypes and workplace myths about meritocracies so women are even less likely to get the opportunity to succeed. The small number of women leaders stand out and are over-scrutinised, with their failings often attributed to their gender. The bar is set much higher for women – US research looking at women leaders in four female-dominated sectors which I quoted found that women are seen as ‘never quite right’ for leadership.

The reasons include age, race, parental status and attractiveness – many of which are usually not applied to men. The excuses are used as a red herring to avoid confronting inherent gender bias and the researchers dubbed it ‘we want what you aren’t’ discrimination. Progression assessment and promotion decisions need to be carefully vetted to avoid these traps and ensure decision making is not biased consciously or unconsciously.

Cover image: Breaking the Boss Bias. Picture: Supplied

As a management writer and journalist I saw much lip service paid to a more collaborative style of leadership (which is also peddled by many management consultants). But the reality is a heroic, masculine, command and control style is still common in many workplaces, and reflected in business media profiles and even in case studies used in business schools where 90% feature male leaders (as I examined in the book).

I don’t think women are naturally more and men less collaborative but women are encouraged to be collegiate and likeable and penalised if they are not. I think the only way to broaden the idea of successful leading has to be intentionally elevating evidence showing different leadership examples. For years I heard that a new generation of younger leaders would change the dynamics of what leadership looks like, particularly in sectors such as IT, but in fact it has barely shifted.

That’s why we need more women in decision making to show a different approach and keep up pressure to shift the parameters – such as former NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern who spoke about kindness as a strength.

So much. But there’s plenty more in the book about what we can all do to break the bias and see fairer outcomes right now.

Picture at top: Catherine Fox. Supplied.

The post Breaking the boss bias: women leaders change the game appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

HIV and AIDS devastated communities across Australia in the 1980s and 1990s. In the midst of this profound health crisis, nurses provided crucial care to those living with and dying from the virus. They negotiated homophobia and complex family dynamics as well as defending the rights of their patients.

A new book, Critical Care, unearths the important and unexamined history of nurses and nursing unions as caregivers and political agents who helped shape Australia’s response to HIV and AIDS. Its author, Geraldine Fela, tells BroadAgenda why this moving slice of history matters.

On the brink of a new pandemic – though none of us knew it then – I travelled around the country interviewing nurses who had been involved in HIV care during Australia’s ‘AIDS crisis’. Between 1983 – the first recorded AIDS-related death in Australia to the introduction of effective treatment in 1996, nurses played an extraordinary role in responding to this profound public health crisis.

The distinct virological nature of HIV brought to light and elevated the crucial role of nurses in patient care. This, combined with a broader political context in which both nurses and patients were challenging the rigidity of the hospital hierarchy, saw a significant change in the relationships between doctors, nurses and patients in many clinical settings.

Nursing was and is a highly feminised profession. The long association of nursing with women has its history in the Nightingale school of nursing, an approach to nursing developed by Florence Nightingale in the second half of the nineteenth century. Under the Nightingale reforms, nursing became a distinct, highly disciplined profession emphasising hygiene, order and hierarchy.

Nightingale nursing was imbued with Victorian ideas of womanhood. The “Nightingale nurse” was a woman, she was self-sacrificing, chaste and middle class in her sensibility. The subordinated position of nurses within the hospital, particularly in relation to doctors, was entrenched in this gendered ideal of nursing. Nurses were taught not to challenge the authority of doctors – who held a monopoly over medicine.

This tradition lasted well beyond the nineteenth century, and is an element of the social dynamics of hospitals and medicine today. For example, it remains the case that the majority of nurses are women and doctors and surgeons men. However, in the 1980s and 1990s and in context of HIV and AIDS care, these rigid hierarchies and roles were shaken.

Cover: Critical Care

The difficult medical circumstances of HIV and AIDS highlighted and elevated the importance of the type of care that nurses provide. This challenged established roles in many of the clinical spaces dealing with HIV and AIDS. Brad Hancock, who nursed at Ward 17 South, the HIV and AIDS ward at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, reflected on this transformation.

Brad recalled the difference between HIV nursing and paediatrics, where he had also worked. In paediatrics, ‘the doctors have all the authority and knew all the answers and you were just carrying out their wishes’. By contrast, in HIV care, he remembered that, ‘[w]hen you came to HIV it was, the nurses are going to be the ones that are going to be caring, that are going to know what’s happening… It was collaborative’.

The confidence of nurses to assert their expertise was also a product of growing union militancy within the workforce. In the late 1970s and early 1980s there was a surge of industrial activity among nurses. For example, in 1986, Victorian nurses took the national stage and struck for fifty days. Simultaneously, an insurgent rank and file had elected radical leaderships in the New South Wales Nurses Association. Nurses were fighting for their pay and conditions, and were also starting to challenge their subordinate role in the hospital.

People with HIV and AIDS were not the generally compliant, elderly patients that many doctors and hospital administrators were used to. Many were young gay men used to asserting their rights. Activists, patients and patient/activists demanded that doctors collaborate with them under a ‘consult, don’t prescribe’ policy’.

Trevor, one of the nurses I spoke to who worked at St Vincents Hospital in Sydney during the crisis, described this new dynamic: ‘the gay men that were dying were loud and angry as a rule’ and that ‘[t]hey would challenge about the therapies, they’d challenge about anything that they could challenge about’.

The confidence and assertiveness of these patients had a profound impact on relationships between healthcare workers and patients. As community nurse Sian Edwards, who also worked in Sydney, recalled ‘The relationship between doctors and patients phenomenally changed. People were learning together… So the relationships equalled’.

When people with HIV and AIDS demanded input into their care and a say over the public health approach to the virus, nurses and their unions stood with them. They opposed discriminatory measures like compulsory HIV testing, long campaigned for by doctors and surgeons, and they supported the aspirations of people living with HIV and AIDS who wanted control and agency over their treatment.

One of the best examples of this occurred in 1991, when the Victorian AIDS Nurses Resource Group—a working group of the Australian Nursing Federation—held a large conference of rank-and-file nurses working in AIDS care. The conference floor passed a series of recommendations related to HIV and AIDS care. These included resolutions opposing mandatory testing. They ‘put the medical profession on notice’ resolving that nurses ‘will not assist you [doctors and surgeons] in carrying out non-consensual HIV testing on people seeking care. We will not assist you in making health care conditional on consent to HIV Testing.’

In the depths of a devastating crisis, affected communities, in Australia predominantly gay men, issued a challenge to the medical establishment; they insisted on having input into their care, they questioned the status quo of drug trials and regulations, and upended the traditional medical hierarchy that elevated the expertise, power and decision-making of doctors and surgeons. In this bold endeavour, they found consistent allies among nurses, who were themselves pushing back on the rigid, gendered hierarchies of the medical system. Change rippled through the broader healthcare system, perhaps the last word on this is best left to Sian:

The relationships between the healthcare professionals and the patient was changing dramatically in HIV. And I think it had an impact on many relationships and hierarchies amongst healthcare professionals now, but it took a while.

Picture at top: Geraldine Fela. Supplied.

The post Nurses redefine patient care during the AIDS crisis appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

Elizabeth Harrower and Shirley Hazzard were among the most admired Australian writers of the 20th century. Since their deaths in the past decade their papers have revealed that they kept up a fascinating correspondence between Sydney, New York and Italy for 40 years.

Hazzard and Harrower: The letters, published by New South in May, charts this riveting and perplexing relationship and the tumultuous times in which they lived.

BroadAgenda editor Ginger Gorman had a chat with the book’s editors, Brigitta Olubas and Susan Wyndham.

Brigitta and Susan: The book collects the revealing personal correspondence between two of Australia’s most significant writers, Shirley Hazzard and Elizabeth Harrower.

Hazzard and her husband moved between New York and Italy, while Harrower lived in Sydney. They were brought together by Hazzard’s mentally unwell mother, Kit, who became a friend and increasing dependent of Harrower.

The two writers met only six times, but for 40 years, from the late 1960s into the twenty-first century, they wrote to each other about their public and private lives, their reading and writing, about politics and world events – from strikes and terrorist attacks to the political emergencies of the Whitlam dismissal and Watergate, and the history-making moments of wars and the fall of the Soviet Union.

Hazzard and Harrower are constantly disturbed by the state of the world – corrupt politics, wars, poverty, climate change – all issues that concern us today. They remind us that we have not improved, but also that people have always feared they lived in the worst of times.

The talk about the pleasures, frustrations and sorrows of friendships with writers such as Patrick White, Christina Stead, Kylie Tennant, Muriel Spark and Lilian Hellman.

While Hazzard’s career soared towards publication of her novel The Transit of Venus in 1980, Harrower’s publishing culminated with her acclaimed fourth novel, The Watch Tower in 1966, which, not entirely coincidentally, was the year she met Kit Hazzard. She gradually stopped writing and did not publish again until her books were revived a decade ago by Text Publishing.

Another mystery is the nature of the friendship itself. In later years Harrower spoke critically of Hazzard, saying that she had become very grand, and had exploited her, and that she had not much admired Hazzard’s writing anyway. For her part, Hazzard was appalled at Harrower’s rudeness to her when she visited Hazzard and her husband in Italy. But their letters continued almost to the end of their lives with mutual interest and sympathy.

Bringing these writers to life through their intimate exchanges and distinct voices brings fresh interest and complexity to their writing. Their books are still in print and remain important, relevant stories about women in complicated, often oppressive relationships at a time when independence was hard won.

The editors of ‘Hazzard and Harrower’, Brigitta Olubas (left) and Susan Wyndham (right). Picture: Supplied

Brigitta: This book grew out of the Shirley Hazzard biography I published in 2022. I had uncovered Harrower’s letters to Hazzard among the large volume of Hazzard’s papers in the basement of her Manhattan apartment after her death in 2014.

Harrower was probably Hazzard’s most prolific correspondent, and I could see from a quick read through how intimate the letters were. Back in Sydney I spoke to Harrower who had placed Hazzard’s letters to her among her papers at the National Library of Australia, but embargoed until both had died. I suggested that a book of their correspondence would be of great interest to Australian readers, but Harrower replied that she didn’t think I should include Hazzard’s letters, just hers. When her letters were returned to Australia, to the State Library of NSW, under the terms of Hazzard’s will, Harrower put an embargo on them too.

After Harrower’s death in 2020 I had access to the letters of both, and I asked Susan, a literary journalist who had known both writers and was planning a biography of Harrower, to work with me on editing and publishing the correspondence.

Susan: I had been interested in Hazzard and Harrower for many years when Brigitta asked me to co-edit the letters. We worked for more than a year on the book, which was more work than you might think. Brigitta transcribed Shirley’s letters, I transcribed Elizabeth’s, about 400,000 words in total. We then sat together making cuts and more cuts, over many months, aiming to create a compelling narrative that flowed and represented their lives and interests.

The letters sometimes alluded to people and events they didn’t explain, so I spent weeks at the National Library in Canberra looking for answers – it was fascinating detective work.

I also continued my research for my planned biography of Harrower, including interviews with many people who knew her. All this, and Brigitta’s earlier research for her biography, informed our editing and contributed to our introduction.

Brigitta: We edited down that huge word count to a little over a quarter of that, first individually, then in long editing sessions that stretched over two or three days at a time through 2023, in one or other of our living rooms.

We agreed and disagreed, then agreed again over what to include, which details were needed, which could be cut. We laughed at almost everything Hazzard’s mother said and did, and at the cruel barbs lobbed by Patrick White at Hazzard (all dutifully passed along by Elizabeth). It was a strangely sociable experience, almost as if we were becoming acquainted with the writers themselves. It was a long and wearying process, but an extraordinary privilege.

Cover: Hazzard and Harrower: The letters

Brigitta: My interest was through my academic work in Australian Literature and my research on women writers who have been neglected or undervalued. I did my Masters on Shirley Hazzard, and over the years have written, edited and published books on both writers.

I visited Hazzard several times in New York to interview her and sort through her papers, and I organised a symposium on her writing which she attended not long before she became frail with age and dementia.

Harrower, too, was helpful with my Hazzard biography. She also came to the launch of a book of essays on her own work that I edited with my colleague Elizabeth McMahon. She was very pleased, even though she was quite deaf and didn’t hear much of what we said.

Susan: I had interviewed both writers as a journalist and became friendly with them without ever knowing about their relationship. I wrote a profile of Shirley Hazzard in New York in 1994, after spending an afternoon with her and her husband, the American writer Francis Steegmuller. Years later my husband and I travelled to Italy with her, a wonderful trip from Rome to Naples and Capri enhanced by her gracious and erudite hosting.

My first knowledge of Elizabeth Harrower came in 1996 when she won the Patrick White Award and I interviewed her by phone. The next time I interviewed her was when her four novels from the 1950s were reissued as Text Classics, and Text published the last novel she had written but put away in 1971. We got on so well that I often went for afternoon tea at her apartment above Sydney Harbour.

Hazzard and Harrower were women of my mother’s age, which interested me. It took great determination for women of that generation to self-educate and become internationally recognised writers against the odds of being female, Australian and from unhappy families. Hazzard did not have children, Harrower was unmarried and childless in her determination to be independent. Both created themselves and hid what they did not want known, all circumstances that are reflected in their fiction. We owe them the respect to keep reading their brilliant books.

Susan and Brigitta: It was a great pleasure to read these beautifully written and typed letters, both as insights into history and as physical artefacts. What good fortune that they kept them for decades and put them with their papers. Libraries are important places. Such collections will be rare or nonexistent in future as people use email and more ephemeral forms of communication.

The post Across continents: Hazzard and Harrower’s intimate correspondence appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.