This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on The Grayzone and was authored by The Grayzone.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

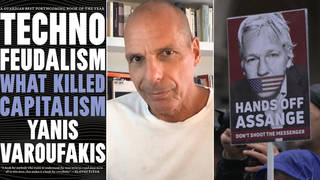

Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, one of the most vocal supporters of Julian Assange, says the United States must drop its espionage case against the jailed WikiLeaks founder. He faults the Australian government for pushing for a plea deal that would allow Assange to walk free from Belmarsh Prison in London in exchange for an admission of guilt. “Julian is never going to plead guilty as if journalism is a crime,” says Varoufakis. He also discusses his new book Technofeudalism, which argues that platforms like Amazon have destroyed the idea of buyers and sellers operating in an open market. “Capitalism was killed by capital,” he says.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

BroadAgenda is featuring a short series of profiles on amazing women and LGBTIQ + folks. You’re about to meet Distinguished Professor of Creative Practice at the University of Canberra, Jen Webb.

I’m very interested in people, and particularly in communities of people, and what provides meaning and connection in their lives. And because I am a creative practitioner myself (I’m a poet), my work over the past decades has focused particularly on how artists – by which I mean anyone who does creative ‘stuff’, anyone who thinks of themselves, at some level, as a creative person who does creative things – how such people fit into society, and how society fits them to itself.

One example of that is what I did for my PhD. I was living in Rockhampton, in Central Queensland, which at least in the 1990s was not a centre for creative excellence. But I knew there were plenty of artists tucked away here and there in the communities up and down the Western line (Yeppoon to Winton). So I set out to talk to local artists, get a sense of their life, of their work and what they make, who they know and what they do in their community, how they make their living, and how they publish their work (exhibition, performance, book or journal publishing etc.).

In between such conversations, I talked to members of local governments, schoolteachers, representatives of community organisations etc., and read the local newspaper if there was one, and visited the local museum where there was one. All this provides a sense of how a community is organised and structured, how its members see themselves, and what they think of their artists and the art things they make and do.

At the end of this research I crafted a narrative about that community that showed what sort of art practices are valued and in what contexts they are valued; Oh, and I wrote a book of short stories about it all, too.

I’m particularly excited about the work I’ve been doing with my colleagues over the past almost-decade on the impact of creative practices on people suffering from trauma or other stress and distress.

We have been conducting biannual month-long workshops with returned service personnel who are wounded, injured or ill, and teaching them skills in creative writing, or visual art, or music-making; and the effects are both positive, and sustained; five years after completing a workshop, they’re still doing very well.

We extended this into similar, but much shorter, workshops with rural and regional communities who have suffered from environmental catastrophe (fires, drought, flood) and seen how writing and talking and drawing et al. can help both the individuals and the community as a whole to recover and rebuild.

Distinguished Professor, Creative Practice at UC, Jen Webb. Picture: Ginger Gorman

I grew up in apartheid South Africa, surrounded by examples of injustice and trauma, and with parents who instilled in my siblings and in me a deep sense of responsibility to try to make the world a better, fairer, kinder, more just place. And for me this has meant writing / art / learning. I was a standard girlie-swot as a kid; I loved learning languages and grammar and history, loved writing stories and poems.

My parents and my school took me to theatres, art galleries and concerts very often; and my parents also took me into places of terrible poverty to deliver blankets and medicines and food. So, I guess my small-child mind drew lines of connection between the worlds of learning and of art, and the obligation to do somethingin society. Later, as an adult, this process of distributing largesse smacks far too much of white saviour behaviour, so I would not now do that. But the principle of paying attention to others, to their lives and aspirations, to their expressed needs; and the importance of knowing more, knowing better – this hasn’t changed. It is just that I don’t unquestioningly assume that I know what others need. At least, I hope I don’t!

I gain immensely from working in research and creative practice with others. When it comes to the arts and health projects, I am one of a group of people doing this work, and my role has been far more in theorising and analysing than in getting out there and conducting workshops.

This work in the arts&health area has had measurable impact: significantly reduced suicide rates, for instance; participants telling us that they are continuing to write, or draw, or drum years after their workshop; and the top rating of ‘high impact’ for creative arts research, in the Australian Research Council’s 2018 Engagement and Impact Outcomes. That the work is having a positive impact fills me with delight, and also with energy to keep learning more about what creative interventions such as these can offer.

Absolutely! I’m a feminist researcher, and a feminist poet, because I’m a feminist person. I don’t think it should be considered a feminist act to work toward a kinder and better-informed society – this is everyone’s task. But until ‘everyone’ has access and equity, it does seem to me important to keep attention on women’s issues and women’s work. One tiny way I try to do this is to foreground women in my research – ensure that when I write articles, and quote from the work of others, at least 50% of those others are women scholars and artists. My colleagues and I used to play a pretend drinking game when listening to lectures from important (usually) international professors of poetry – drinking an imaginary shot each time they mentioned a woman poet.

Usually, after the lecture, we’d agree that if there had in fact been any alcohol involved, we would be stone-cold sober. (And often one of us would ask the Important Speaker about the paucity of women in their talk, and watch the defensive response.) If we don’t talk about women, they are, or seem, invisible. We need to support each other, and each other’s work.

If I consider what might have enchanted me, probably the greatest enchantment has been experiencing and researching the remarkable benefits of creative collaboration.

Poets tend to be solitary creatures, but when they work together, a lot of the anxiety seems to fall away, and greater leaps of creativity can emerge.. I have been part of several interconnected poetry collaborations over the last decade and found it literally enchanted – I am cast under the spell of working in this way. At the heart of it is a 10-year-old collaboration we call the Prose Poetry, where a shifting group of poets email off-the-cuff poems – fast writing, barely edited – to everyone in the group, and these spark new poems in response. All sorts of creative and scholarly works have Catherine-wheeled off this Project over the years. This is enchanting – it keeps me writing, and thinking, and playing, and feeling part of something I care about.

The academic world gets a bad rap, so often. We’re called elitist, eggheads, Ivory Tower dwellers; or we bemoan our sense of being overworked and underpaid, tied up in red tape, writing articles no one will ever read. The poetry world is no better: poetry operates outside the economy; and who reads poems, except other poets (and excepting at weddings and funerals, of course)? However – there has to be a however – both are also fields of extraordinary richness, measuring wealth in ideas, creative thinking and practice, opportunities to connect with others, and to pursue the something you are passionate about.

Poetry and the academy: both are tough gigs, but for me they have been life-making, life-affirming. And they’re enchanting – I’m still here, captivated by the power of their magic.

The post Inspiring women: Jen Webb appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg says NATO allies are committed to doing more to ensure that Ukraine “prevails” in its battle to repel invading Russian forces, with the alliance having “significantly changed” its stance on providing more advanced weapons to Kyiv.

Speaking in an interview with RFE/RL to mark the second anniversary of Russia launching its full-scale invasion of its neighbor, the NATO chief said solidarity with Ukraine was not only correct, it’s also “in our own security interests.”

“We can expect that the NATO allies will do more to ensure that Ukraine prevails, because this has been so clearly stated by NATO allies,” Stoltenberg said.

RFE/RL’s Live Briefing gives you all of the latest developments on Russia’s full-scale invasion, Kyiv’s counteroffensive, Western military aid, global reaction, and the plight of civilians. For all of RFE/RL’s coverage of the war in Ukraine, click here.

“I always stress that this is not charity. This is an investment in our own security and and that our support makes a difference on the battlefield every day,” he added.

Ukraine is in desperate need of financial and military assistance amid signs of political fatigue in the West as the war kicked off by Russia’s unprovoked invasion nears the two-year mark on February 24.

In excerpts from the interview released earlier in the week, Stoltenberg said the death of Russian opposition leader Aleksei Navalny and the first Russian gains on the battlefield in months should help focus the attention of NATO and its allies on the urgent need to support Ukraine.

The death of Navalny in an Arctic prison on February 16 under suspicious circumstances — authorities say it will be another two weeks before the body may be released to the family — adds to the need to ensure Russian President Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian rule does not go unchecked.

“I strongly believe that the best way to honor the memory of Aleksei Navalny is to ensure that President Putin doesn’t win on the battlefield, but that Ukraine prevails,” Stoltenberg said.

Stoltenberg said the withdrawal of Ukrainian forces from the city of Avdiyivka last week after months of intense fighting demonstrated the need for more military aid, “to ensure that Russia doesn’t make further gains.”

“We don’t believe that the fact that the Ukrainian forces have withdrawn from Avdiyivka in in itself will significantly change the strategic situation,” he said.

“But it reminds us of that Russia is willing to sacrifice a lot of soldiers. It also just makes minor territorial gains and also that Russia has received significant military support supplies from Iran, from North Korea and have been able to ramp up their own production.”

Ukraine’s allies have been focused on a $61 billion U.S. military aid package, but while that remains stalled in the House of Representatives, other countries, including Sweden, Canada, and Japan, have stepped up their aid.

“Of course, we are focused on the United States, but we also see how other allies are really stepping up and delivering significant support to Ukraine,” Stoltenberg said in the interview.

On the question of when Ukraine will be able to deploy F-16 fighter jets, Stoltenberg said it was not possible to say. He reiterated that Ukraine’s allies all want them to be there as early as possible but said the effect of the F-16s will be stronger if pilots are well trained and maintenance crews and other support personnel are well-prepared.

“So, I think we have to listen to the military experts exactly when we will be ready to or when allies will be ready to start sending and to delivering the F-16s,” he said. “The sooner the better.”

Ukraine has actively sought U.S.-made F-16 fighter jets to help it counter Russian air superiority. The United States in August approved sending F-16s to Ukraine from Denmark and the Netherlands as soon as pilot training is completed.

It will be up to each ally to decide whether to deliver F-16s to Ukraine, and allies have different policies, Stoltenberg said. But at the same time the war in Ukraine is a war of aggression, and Ukraine has the right to self-defense, including striking legitimate Russian military targets outside Ukraine.

Asked about the prospect of former President Donald Trump returning to the White House, Stoltenberg said that regardless of the outcome of the U.S. elections this year, the United States will remain a committed NATO ally because it is in the security interest of the United States.

Trump, the current front-runner in the race to become the Republican Party’s presidential nominee, drew sharp rebukes from President Joe Biden, European leaders, and NATO after suggesting at a campaign rally on February 10 that the United States might not defend alliance members from a potential Russian invasion if they don’t pay enough toward their own defense.

Stoltenberg said the United States was safer and stronger together with more than 30 allies — something that neither China nor Russia has.

The criticism of NATO has been aimed at allies underspending on defense, he said.

But Stoltenberg said new data shows that more and more NATO allies are meeting the target of spending 2 percent of GDP on defense, and this demonstrates that the alliance has come a long way since it pledged in 2014 to meet the target.

At that time three members of NATO spent 2 percent of GDP on defense. Now it’s 18, he said.

“If you add together what all European allies do and compare that to the GDP in total in Europe, it’s actually 2 percent today,” he said. “That’s good, but it’s not enough because we want [each NATO member] to spend 2 percent. And we also make sure that 2 percent is a minimum.”

This content originally appeared on News – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty and was authored by News – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Chicago is the economic core of the vast hinterland that spans the United States Midwest called the Rustbelt. Unlike other major Rustbelt cities like Baltimore and Detroit, on the surface Chicago seems to have weathered the industrial decline that gave the region its nickname. Yet a closer look at the city reveals an uneven pattern of capitalist development: decades of state and private investment…

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

Updated October 19, 2023, 5:38 p.m. ET

Authorities in China have banned a book about the last Ming dynasty emperor Chongzhen after online comments said its analysis could apply to current Communist Party leader Xi Jinping.

“Chongzhen: The hard-working emperor who brought down a dynasty” by late Ming dynasty expert Chen Wutong recently disappeared from online bookstores, including the website of state-run Xinhua Books, with multiple searches for the book yielding no results on major book-selling platforms this week.

Meanwhile, keyword searches for the book and its author on the social media platform Weibo yielded no results on Thursday.

Current affairs commentators said the book has likely been removed from public view after online comments drew parallels between its analysis of the fall of the 1368-1644 Ming dynasty and China’s current situation under ruling Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping.

Many online comments picked up on a particular line in Chen’s book: “With one bad move following another, the harder he worked, the faster he brought the country to ruin.”

“From the Ming Dynasty all the way to the present day,” chuckled a post on the “Stupid Stuff from China” Facebook page dated Oct. 17.

“It’s obvious what it’s hinting at,” commented one reader.

Another reader likened Xi to several emperors who were the last of their dynasties.

“Chongzhen, Daoguang, Pu Yi, Winnie [the Pooh], so many like this,” the reader said, using Xi’s nickname Winnie the Pooh, whom he is said to resemble.

Current affairs commentator Wang Jian said the book’s ban was likely down to that sentence, which resonates in people’s minds.

“The book wouldn’t have much of an effect on [Xi], except that it reflects what everyone is thinking,” Wang said. “Xi Jinping has been going against common sense and the will of the people in recent years — everyone has reached a consensus about that.”

“[The book shows that] if someone tries to abuse their power, misfortune will befall them, so it has become a sensitive topic,” he said. “It would never have been banned if it didn’t speak to that social consensus and public feeling.”

Former Hong Kong bookseller Lam Wing-kei, who now runs a bookshop on the democratic island of Taiwan, said any book in China that carries a potentially political message can be banned at any time.

“The top priority for the [Chinese Communist Party] regime is to maintain its grip on power,” Lam, who was detained for months by state security police for selling political books to customers in mainland China, said.

“As soon as they find a book with ideological implications for the regime or its hold on power, they will list them as banned books,” Lam said, citing the banning of the “Sheep Village” series of children’s picture books in Hong Kong.

“The people in power make the decisions, and also determine the criteria for banning a book, which can’t be rationally understood,” he said.

Current affairs commentator Fang Yuan said it’s common in China, where people can’t express their opinions freely, for public dissatisfaction with the government to emerge indirectly, through historical references.

He said people have seemingly responded to the ban by selling used copies of the book at hugely inflated prices on second-hand book-trading platforms, which are less stringently regulated.

One copy of the book was even listed on the Confucius online second-hand bookstore for 1,280 yuan (US$175), 27 times the listed price for a new copy.

“When there’s no hope of playing hard-ball, the public and civil society expresses its anger by playing a softer game, as a way to curse out the government,” Fang said.

“[This book ban] shows that the situation is very sensitive and has reached a stage where everything is tense and everyone is on guard.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Eugene Whong.

Update changes the image to the most recent edition of the book.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Chen Zifei for RFA Mandarin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

I’m a white-passing Mohawk woman whose paternal family is from Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Canada. I write and edit. I love horror and professional wrestling, which have more in common than you’d think.

This book originally started as a short story about the experience of being a new mother. I had my son when I was 18, and I felt in some ways tricked about what being a new mom actually looked and felt like – not just emotionally, but also physically, in my body.

It seemed like there was some big conspiracy to keep us from knowing the full, often ugly truth of what it takes to care for a newborn infant.

The story never seemed finished, though, so I put it away, taking it out from time to time to tinker with it. It was only when I started reflecting on my own love of genre-bending work, and considering that the protagonist of another short story that I couldn’t figure out was actually the same protagonist for this story, that I realized these were the missing pieces that would slide the entire thing into focus. And so it became a novel!

Rather surprisingly, after I decided that Alice would be struggling with psychosis, I ended up having a full manic episode with psychosis myself. It took a while to come down from that and be able to look back and assess the situation clearly. When I did, though, it illuminated the experience of psychosis for me. I knew that everything I assumed about the experience was totally wrong – and I knew intimately what stereotypes were levied against people in the thrall of psychosis, and the devastating pain it produced. All of this helped me shape the novel into what it is now.

The cover of “And Then She Fell.” Image: Supplied

Alice is funny, caring, and insightful, with a deep sense of duty – too deep, in fact. Since she was young, Alice has had to carry far more responsibility than many other kids her age, putting her in a position where she’s become used to putting everyone else’s needs, desires and expectations first.

This has, unfortunately, developed into a belief that you show others you love them by forcing yourself to become whatever they want or need you to be, even if it hurts you. It’s very hard for Alice to understand who she is separate from those she loves and cares for, or for her to value herself apart from what she’s able to do for those around her.

Having lived on the Six Nations reserve her whole life, Alice is acutely aware of what reserves were actually designed for: to isolate her people and push them into ruin, ideally forcing them to move into cities and give up their identity, language and culture, so that Canada no longer had to uphold any historical treaties made with them. Which means she’s also just as aware of the unintended side effect of reserves: that our people were all together, and therefore could keep our language and culture alive – at least, as much as was possible, considering the laws Canadian politicians were continually passing forbidding us to do so.

White people, who society has ensured do not have to face these histories every day, can therefore easily relegate all of it to some distant past. Or worse: they can altogether ignore it.

For Alice and her family, on the other hand, this history of dispossession, intergenerational trauma, and cultural and linguistic genocide lives in their every action and possibility, in their very genes.

They couldn’t ignore it if they tried. In fact, the more Alice tries to ignore this and pretend that everything is fine to assuage her white husband and neighbours, who are uncomfortable and passive aggressive whenever “race” is even mentioned, the more this history rears its head and forces her, and them, to acknowledge it.

After my own experience with psychosis and mania, it occurred to me how much I’d previously thought I knew and understood about them were not just wrong, but offensively wrong, contributing to stereotypes and injustice being levied against other mad folks. I wanted to use this text as a way to speak back to those assumptions.

Alicia Elliott. Picture: Alex Jacobs-Blum

As for the levity, I think that those who have experienced great despair are more likely to appreciate the power of humour, to understand the way it acts as a sort of nightlight, helping people to see, and hope, in the dark. Indigenous people are some of the funniest people I know, and so are other mad folks, so it felt important to incorporate that humour into the book.

As I sort of hinted at above, I think there’s a lot of effort put into giving new parents the (false) impression that everything from pregnancy to childbirth to raising a child are pure and uncomplicated joys. While that does play into it, too, I found that there was also a lot of grief, guilt, despair and loneliness. The more I spoke to other parents about it in private, the more I realized that this complicated duality was the actual experience of parenthood – not the sort of joyous fairy tale we’ve all been lead to believe.

I think the more we normalize this experience of parenthood, the more we temper the expectations of new parents, the more we give new parents room to voice and then deal with their own difficulties. It’s important we look at these sorts of things realistically, not idealistically, because we live in the real world, not some imaginary ideal one. We all need to know we’re not alone.

I’m a big fan of voice-driven fiction. If you develop a compelling enough voice, it doesn’t matter what you have the character doing, you’re going to make the reader want to stay with them through it. I wanted Alice’s voice to be that sort of compelling vehicle, especially since she was navigating early motherhood, which is generally—and in my opinion, unfairly—considered to be very boring to all who aren’t parents.

Obviously, I’m far too long-winded to be given this sort of question, but I’m also self-aware, so I’ll say no.

The post “It illuminated the experience of psychosis for me” appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

The post Blak friends in a ‘friendship recession’ appeared first on IndigenousX.

This post was originally published on IndigenousX.

Menstruation is something half the world does for a week at a time, for months and years on end, yet it remains largely misunderstood. Scientists once thought of an individual’s period as useless, and some doctors still believe it’s unsafe for a menstruating person to swim in the ocean wearing a tampon.

A new book called “Period” by Kate Clancy counters the false theories that have long defined the study of the uterus, exposing the eugenic history of gynecology while providing an intersectional feminist perspective on menstruation science.

I’ve been studying menstrual cycles and periods for over twenty years. What first drew me to them in college was the idea that you really could do research on something that you personally find interesting. I didn’t know anyone in academia or research – I didn’t know you really could study just about anything. And up to this point my exposure to periods was what I learned from my doctor and from sex ed in grade school.

The scholarly study of periods opened up a whole different way of understanding the body – we can look to the historical study of the body, we can look to different ways of measuring things, we can understand variation not just pathology. It was the beginning of my love of biological anthropology and human biology more broadly.

I wanted to write about periods for the same reason – I want more people to know what I know, that menstrual cycles are variable, responsive to environment, not inherently gross, and actually kind of weirdly cool.

Some of the misunderstanding is wilful and some is not. I think when people make jokes about “blood coming out of her eyes or wherever” (Trump) or giving a cis man a tampon as a way of saying he is weak (Tiger Woods) – two things that have happened in recent years among famous men in the US at least – then yes, it’s wilful.

Equating menstruation with weakness or emotional instability is such a tiresome, tired way of conceptualizing the uterus. I mean, if you’re going to be sexist, at least try to be clever about it.

Another wilful misconception, to my mind, is in evolutionary psychology, where they seem to want to make everything about fertility detection. Humans are often said to be “concealed ovulators,” which isn’t exactly accurate but means we don’t have really obvious changes in behavior, or sexual swellings, or other ways of indicating our fertile period. Bros who want to know exactly when menstruating people are most fertile are obsessed with “detecting fertile periods” and with knowing our sexual preferences at different phases of the menstrual cycle to avoid getting cuckolded (the venn diagram of incels and certain fields in evolutionary psychology is a near circle).

They are convinced there is some sort of intentional strategy that women and other menstruating people participate in that they can game to increase their own chances of getting a girlfriend, or something.

The cover of “Period: The Real Story of Menstruation”. Picture: Supplied

But I have also encountered so very many people who fundamentally misunderstand what a period is, why we have them, and what is going on in their or their loved ones’ bodies. When I was a kid I remember a friend’s boyfriend who thought menstrual blood came out of the belly button. More recently, I interviewed a high school biology teacher who has had students who thought periods were more like bowel movements, where you could hold them until you went to the toilet.

Almost every man who has learned I study menstrual periods (and many women) have asked me if they synchronize among people who spend a lot of time together (they don’t). And something I’ve heard from many people as they’ve been reading my book is that they had no idea how much variation in menstrual cycles and periods was in fact quite normal – adaptive even, as we are supposed to be responsive to environment. It’s been a relief to them to know they are not “irregular” but in fact typical menstruating people.

I say it has a eugenic history because it has a eugenic history. Gynaecology was founded on a number of things:

1) Pushing out midwives with massive experiential knowledge, most of whom were Black and brown, criminalizing their work, and shaming them out of the profession – maternal mortality increased when they did this.

2) Many of the procedures and practices we have today came from the unanesthetized and nonconsensual experimentation on enslaved people

3) Gynaecology is founded on the idea that we need to preserve the fertility of white women while limiting the fertility of “undesirables” – people of color, disabled people, incarcerated people. As late as 2010 we were still sterilizing incarcerated people (mostly people of color) after pressuring them repeatedly to consent.

Racism is central to the conversation on the history of gynaecology and the ethics of the discipline and its practitioners because the race of the patient is so often central to the type of care they receive.

Because the idea that there can be one “normal” menstrual cycle is just bad science. Research shows that ovarian hormones are incredibly variable, even among ovulatory cycles that are fecundable (meaning, that person is likely able to get pregnant that cycle if they try). And we’ve known this for at least forty years. My lab shows it’s not just that the overall quantities are variable, but that the pattern of expression through the cycle is variable.

So that picture you saw when you were learning about what a menstrual cycle is in grade school is really not accurate. In fact, in our samples we see that pattern in less than a third of ovulatory cycles.

What this means is that when we think we are weird, or not normal, or there is something wrong with our cycles… a lot of the time that isn’t true. Of course if a person is experiencing pain, infertility, or other symptoms it is crucial they get seen by a doctor. It is also important, though, to recognize that some amount of variability we experience just means our systems are functioning as they should.

Picture: Vulvani Gallery: Free stock photos around menstruation

Medical betrayal is a subset of a larger concept developed by Dr. Jennifer Freyd and others called “institutional betrayal.” Freyd defines institutional betrayal as “wrongdoings perpetrated by an institution upon individuals dependent on that institution, including failure to prevent or respond supportively to wrongdoings by individuals (e.g. sexual assault) committed within the context of the institution.”

Medical betrayal is the kind of betrayal experienced by medical institutions: both at the provider-level and system-level. When people are not believed, when they have to advocate for themselves for a decade or more to receive a diagnosis, when their ailments are understudied, when dealing with insurance is a full time job – that’s medical betrayal.

People with uteruses have a lot of betraying experiences in the medical system, and over time that can lead to a real loss of trust in science and in medicine. Sometimes this leads them towards treatments or methods that end up helping them a lot, other times they end up in the arms of charlatans. While I think there are limitations to Western medicine, it has many incredible uses and I find it really sad not only that the limitations are so centered around gonadal health, autoimmune and chronic diseases, and stigmatizing of fat people, but that this means that times when people with uteruses could really use health care, they may stop trying to get it.

Periods are a fascinating case study for biology: instead of relegating the menstrual cycle to a short mention in sex ed it really should be featured in high school biology classes. I mean, you have tissue remodeling, you have immune regulation, you have the uterus itself which is basically the original 3D printer! Why don’t we study why and how humans menstruate, and how the uterus works, at this time?

I think if we bring back some of the wonder and curiosity it works better to reduce stigma than some efforts I’ve seen to normalize period blood (some of which, in my opinion, backfires because all it does is stimulate a disgust reaction in all the people who are already in the stigma camp). Whenever I talk to doctor friends I am appalled at how little they learn about the typical menstrual cycle or how or why periods do what they do (or, though this is a topic for another time, how they learn next to nothing about perimenopause and menopause). If the people who treat menstruating bodies don’t themselves know anything about periods I don’t know how we can get to a point where they are less stigmatized.

When I was a very junior scholar, I expressed interest in studying endocrine disrupting chemicals and how they might affect menstrual cycles. I was immediately told by someone very senior that “they don’t do anything” and that I should look elsewhere in my research.

Well, now we know that EDCs are everywhere, they are intensely harmful, and they do directly influence menstrual cycles, egg development, possibly even period pain or endometriosis. There are EDCs in tampons, pads, period underwear – but also in our drinking water, our food, and the air we breathe. A lot of this is due to fossil fuel extraction, plastic production, and exposure to plastics themselves.

These data were surprising to me not just because they contradicted what an expert once said to me, but because I couldn’t figure out why this wasn’t a bigger deal. Plastics, disinfecting our water, particulate matter in the air – as we completely destroy our planet we are destroying human health. I cannot imagine a more important thing to sound the alarm on, and there are decades of incredible work showing in every way we can imagine that human damage to our planet is also damage to humans themselves – damage we can’t individual-solution our way out of. We need to fundamentally rethink the way we engage with the world and the obligations we have to each other and the planet.

While I only put a little of this in the book, I ended up writing a separate article on this for American Scientist and have continued to follow this research both in collaborations in my lab as well as my next writing project.

I hope talking about periods opens up bigger conversations for them around disability justice and what it means to create a true public where all humans can participate. Right now we have publics that are not fully accessible to children, caregivers, disabled people, immune compromised people, people of color, and menstruating people…to name just a few, and of course, these identities all can intersect.

It’s not safe to be a Black person driving on the highway; it’s not safe to go to a crowded indoor space as an immune compromised person; it’s not safe to breathe the air some days as a pregnant person.To participate in public life, too many people have to take risks for their physical and mental and emotional health – risks that we could reduce through reduction of fossil fuels, slowing of climate change, better ventilation and filtration of indoor air, an end to racist policing as well as abolition from the perceived need for policing at all.

I also want people to feel hopeful at the end of the book. The future is not inevitable, it’s not already set in stone. The future is up to us: what we imagine, what we work for, what we fight for.

Maybe the piece I imagine is about having better ways of having periods in public, and being able to suppress periods as needed with fewer side effects.

But maybe this gets you started imagining better air in your workplace, or an end to natural gas use in your home – and from there you dream bigger and bigger and bigger, working with coalitions of interested groups towards something brighter and ever more exciting.

I think that’s it! Thank you for the chance to talk about my book – I do hope people buy it, and read it, and use it to enjoy cool science and dream of a better world.

Period: The Real Story of Menstruation, out now

Picture at top is from Vulvani Gallery: Free stock photos around menstruation

The post Periods are “actually kind of weirdly cool” appeared first on BroadAgenda.

Endometriosis is a painful, chronic, incurable illness that affects one in nine people who menstruate. Gynaecologist and author Dr Susan Evans defines it as “a condition where bits of tissue like the lining of the uterus are found in places outside the uterus where they shouldn’t be”. Endometriosis symptoms can include, but are not limited to: debilitating pain during periods, abdominal bloating, nausea, fatigue, low mood and depression, anxiety, pain with sex, adhesions, painful bowel movements and/or urination, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.

Patients can have some, none or all of those symptoms. There are four stages of endometriosis with one being the least endometriosis lesions and four being the most, but there is no correlation between stages of endo and levels of pain.

You could have stage one endo and severe pain or stage four endo and no pain. We still have tons to do in terms of research and awareness to work out why and how that is so.

I was born and raised in Canberra and moved to Adelaide at 14 years old. Just when we were about to move, I had a sudden attack of abdominal pain and I fainted on our icy cold Canberra bathroom tiles. My mum suggested it was probably period pain because she suffered similar and was a fainter as well. Later that day, I got my first period. Figuring it was normal and just the way period pain worked, I got on with my life, and we moved to Adelaide where I endured these painful, dizzy and nauseating episodes every month.

When I was 19, I had a working holiday in Cairns where a friend told me she’d been diagnosed with ‘endometriosis’ and described her symptoms to me. They matched my own, so I took myself off a doctor and he sent me away with a diagnosis of ‘partying too hard’ after chastising me for diagnosing myself (where did you get your medical degree? he asked).

At 22, I was back on the east side, living in Jindabyne and working at Blue Cow Mountain. I woke early one morning in severe pain, staggered to my local GP and promptly collapsed on the waiting room floor. I was whisked off in an ambulance to Cooma and my appendix was whipped out.

My surgeon visited me after the procedure and said he’d removed a healthy appendix. I asked, what’s wrong with me, then? And he said, You’ve probably just got your knickers in a twist over something.

Back in Adelaide for many years, I visited doctors complaining of pain, only to be told it was all in my head, until I was 35 and pregnant with a much-wanted baby that turned out to be a cornual ectopic pregnancy (a rare and dangerous condition where implantation occurs on the outside corner or in the cavity of the ‘horn’ of the uterus). This was the first of 11 pregnancy losses and no surviving pregnancies.

After having the ectopic removed via caesarean surgery, I was in more pain than ever, so I kept going back to my specialist asking for help and he kept saying I was fine, just grieving and/or stressed (eg, all in my head). After 12 months of dismissal, he reluctantly agreed to do a diagnostic laparoscopy but assured me there was nothing wrong with me. That surgery revealed stage four endometriosis. Finally, I had answers. Finally, it wasn’t all in my head. Finally, I could start healing. Because, when you spend 22 years trying to fix a head that isn’t sick, your head gets a little sick. So, I had a lot of work to do to forgive myself.

The cover “Endo Days.”

Endo Days is a journalistic memoir that’s part narrative, part instruction manual and part comedy routine. It threads my story through interviews with a diverse range of ‘endo friendos’ across Australia, including the experiences of trans, queer, neurodivergent, younger, older, First Nations, metropolitan and rural Australians. The book offers tips and tricks for living well with chronic illness and takes the reader through my journey from misdiagnosis to treatment, through medical gaslighting, pregnancy losses, raising step-kids and a foster son, and working towards educating others.

When I was first diagnosed, I was angry and confused. I was sent home with this word, ‘endometriosis’ but no further information. I googled and was even more confused. I am a teacher by trade, so I immediately wanted to get some resources out there for people like me who were diagnosed late and feeling lost in the void.

But I also wanted to educate 14-year-old me (and her mum) that pain like that isn’t normal and there are better ways we can advocate for ourselves.

So when Wakefield Press approached me to write the book I knew I wanted to write the resource that would have helped me when I was first trying to navigate this illness.

Someone once said to me, ‘there’s nothing funny about chronic illness’ and that felt like a challenge!

In my family, we have always used humour to diffuse tragic, difficult or awkward situations and my journey through endometriosis has been all of those things. But I also learn best through laughing. My husband Matt and I wrote our comedy cabaret (also called Endo Days) about our experiences with endo together.

In the show, we sing and joke about things like pain, the partner experience, medical gaslighting, fertility issues, being excluded from the ‘Mum Club’ because I didn’t birth my three children, unsolicited advice (have you tried yoga?) and there’s even a rap about suppositories. The show is great fun and a well-earned laugh for people with pain and their supporters.

It’s therapeutic for me as well, but the best bit is giving people who feel like there’s no hope and nothing out there for them an hour of comedy and song that is entirely relatable and allows them to feel validated and important, which they deserve.

Libby Trainor Parker is also a comedian. Picture Supplied/Craig Egan

It took two decades for me to be diagnosed with endometriosis. I went to so many doctors complaining of pain, moods, fertility issues, bloating, nausea, bladder and bowel pain. And every time, I was told it was stress and anxiety, tiredness or a mystery virus. I was never referred to a gynaecologist until an ectopic pregnancy accidentally took me to a specialist who also said it was in my head, but who finally diagnosed me.

Endometriosis, in addition to many illnesses that affect women and people assigned female at birth, is still underfunded, under-researched and lacking awareness. Many of us are sent away with a prescription of ‘paracetamol and a lie down’ or ‘get some exercise and take up a hobby’ or ‘deal with it, it’s a women’s lot’. One woman told me a story that she was instructed by a GP to, ‘have an affair because then you’ll lose weight and feel better about yourself and your pain will go away’.

But it’s hard for doctors as well, especially GPs, because they are expected to be experts on everything from coldsores to cancer, so they need us to know our bodies better so we can go to see them armed with more information and the confidence to describe our symptoms better.

And I think things are changing. We are talking more. There is more information out there and, what was once a taboo topic is becoming more acceptable to discuss.

I see a generation of younger people coming through who are gutsier and more informed than I ever was and it gives me hope that endometriosis will be easily diagnosed and treated in the near future.

Patients are often told pregnancy or hysterectomy will cure endometriosis, but there is not yet a cure for endo. People are also often told endo causes infertility, but that is also not always the case. There is so much that is unknown about endometriosis, but telling someone to get pregnant or have a hysterectomy before they’re ready to is extreme and dangerous!

I want people with endometriosis to feel seen, heard, understood and validated, and I want them to know they are not alone. There are people fighting for them every day and working hard to get this illness better recognised so we can fix it. I want them to know there is change on the horizon and there is hope. I want partners, parents, supporters and health practitioners to feel acknowledged and that we are grateful to them.

Living with chronic illness is so hard and we’re all doing our best. We can’t be warriors every day. Some days, I’m too tired to fight and I go back to bed and try again tomorrow. And that’s okay. I want people with endo to know that they’re enough, what they’re doing is enough and I’m proud of them for surviving.

I am hoping to bring my show and book to Canberra, so please come and see me so I can be the Homecoming Queen.

The post Endometriosis isn’t funny. Libby doesn’t agree. appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

Chinese authorities have banned a book on the history of the Mongols, citing “historical nihilism” – a term indicating a version of history not in keeping with the official party line – in what appeared to be a concerted attack by Beijing on ethnic Mongolians’ identity.

Orders have been sent out to remove “A General History of the Mongols” by scholars in the Mongolian Studies department of the Inner Mongolia Institute of Education should be removed from shelves, the pro-Beijing Sing Tao Daily newspaper reported.

It cited an Aug. 25 directive from the Inner Mongolian branch of the government-backed Books and Periodicals Distribution Association.

The move comes after President Xi Jinping called for renewed efforts to boost a sense of Chinese national identity in a visit to the northwestern region of Xinjiang.

Xi vowed to double down on China’s hardline policies toward the 11 million mostly Muslim Uyghurs who live in the region, warning that “hard-won social stability” would remain the top priority, along with making everyone speak Mandarin rather than their own languages.

And his warnings seemed to apply to other regions, too.

“Forging a strong sense of community for the Chinese nation is a focus of .. all work in areas with large ethnic minority populations,” Xi said in comments paraphrased by state media reports.

“Education on standard spoken and written Chinese must be resolutely carried out to enhance people’s consciousness and ability to use it,” he said.

Ethnic Mongolians, who make up almost 20 percent of Inner Mongolia’s population of 23 million, increasingly complain of widespread environmental destruction and unfair development policies in the region, as well as ongoing attempts to target their traditional culture.

Clashes between Chinese state-backed mining or forestry companies and herding communities are common in the region, which borders the independent country of Mongolia, with those who complain about the loss of their grazing lands frequently targeted for harassment, beatings, and detention by the authorities.

Historical narrative

The banned book, published in 2004, was previously lauded for its work in “connecting the history of Mongolia from ancient times to the medieval period, making the history of Mongolia more complete,” according to a Baidupedia entry still available on Friday.

“Systematizing, organizing, and using a scientific approach can help the world better understand China’s five thousand years of glorious history, strengthen the unity of the Chinese nation, and make Chinese culture and history more prosperous,” said the entry, which must have once been approved by government censors.

Analysts said the book is already fairly nationalistic in tone, and describes the Mongols as part of the Chinese nation.

But the ban comes as the authorities are increasingly concerned about a growing sense of Mongolian identity among ethnic Mongolians living in China.

“A lot of Mongolian scholars and Mongolians in general don’t like this book because it describes the Mongols as a people of China,” Yang Haiying, a professor at Shizuoka University in Japan, told Radio Free Asia. “The Mongols have never considered themselves to be a Chinese people.”

Nonetheless, the book is now considered to contribute to a pan-Mongolian identity because it didn’t go far enough in making the Mongols appear to be historically part of the Chinese nation, Yang said.

A pro-government comment on the social media platform Weibo hit out at the book for “historical nihilism.”

“Criticizing the pan-Mongolian nationalist trend is conducive to #cultivating the consciousness of the Chinese national community, conducive to #ethnic exchanges, exchanges, and integration#, and conducive to #forging a strong sense of the Chinese nation’s community !,” user @XiMay1 wrote on Aug. 29.

Ending Mongolian instruction

At the start of the academic year in 2020, China announced it would end Mongolian-medium instruction in schools, prompting angry protests and a wide-ranging crackdown across the region.

Taiwan-based strategic analyst Shih Chien-yu said the banning of the book sends a more general message to China’s ethnic Mongolians.

“There are still a lot of Mongolian cadres in the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party of China, a lot of Mongolian intellectuals and officials, while most of the ethnic minority intellectuals in the various central nationalities colleges and university-level schools are Mongolian,” he said.

“The main reason for banning the book is to warn them that they should believe they still have any clout within the regime,” Shih said. “Don’t put up any resistance behind our backs, because we can take away your power at any time.”

In 2018, Chinese authorities detained Lhamjab A. Borjigin, a prominent ethnic Mongolian historian who gathered testimony of a historical genocide campaign by the ruling Chinese Communist Party, prosecuting him on charges of separatism.

He was handed a one-year suspended jail term for “separatism” and “sabotaging national unity,” then released under ongoing surveillance.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The following article is a condensed version of a research paper delivered at the ANU Gender Institute symposium on ‘Understanding Coercive Control’ that explored coercive control from multiple inter-disciplinary perspectives.

The issue of coercive control – what is it, how do we recognise it, should it be criminalised – has been subjected to significant media and public attention in the last few years. This, in conjunction with the fact that the term ‘coercive control’ was only coined in 2007 by sociologist Evan Stark, contributes to the assumption that coercive control is a new phenomenon.

However, the patterns of behaviours designed to intimate, control, and isolate an individual that Stark classifies as coercive control have been a feature of intimate partnerships since at least the nineteenth century.

Notably, it was as early as the 1880s that these behaviours were beginning to be criticised and recognised as unacceptable masculine marital behaviours, or as abuses of patriarchal authority. Through law and literature, wives and women were claiming that a husband’s unquestioned control over all aspects of his wife’s life was an unacceptable abuse of patriarchal power – with some divorce court judges supporting this assertion.

The 1886 novel of Rosa Praed, The Right Honourable, is an enlightening example of how colonial women used literature to critique domestic violence in all its forms, including the non-physical and especially patterns of behaviour that would now be termed coercive control. Despite Praed being Australia’s most popular and well-known female author during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, renowned for her damning portrayals and critiques of marriage, few of her books have been reprinted since their original publication.

The Right Honourable is no exception to this – despite being reprinted multiple times throughout the 1880s and 1890s, it has been out of print for a century.

Zoe Smith believes the 1886 novel of Rosa Praed, The Right Honourable, is an enlightening example of how colonial women used literature to critique domestic violence in all its forms. Picture: Supplied

In The Right Honourable, Crichton Kenway is introduced as a man ‘who seemed fairly fitted to be a hero of romance of the conventional order. He was tall, upright, good-looking, well dressed, and had an air of breeding’. A politician who moves in all the right social circles, he and his Australian wife Koorali seemingly have the perfect relationship. However, Crichton’s marital behaviour means that the marriage between himself and Koorali is clearly no ‘romance of the conventional order’.

The marriage is characterised by psychological and verbal abuse directed towards Koorali, with Crichton’s behaviour comprehensible to the modern reader as behaviour we would now term ‘coercive control’ and ‘gaslighting’.

Crichton tells Koorali how to dress, he regulates her behaviour at balls to ensure she is constantly working to his advantage in using her feminine wiles to charm his superiors, he reads her letters over her shoulder, he criticises and monitors her expenditure. All this occurs in conjuction with his verbal abuse designed to belittle and demean her, ‘crude, hard things in a way that hurt her like a blow’.

As Praed describes, ‘Crichton, though never absolutely rude or rough, had a rasping, overbearing manner at home – a way of harking upon mean detail, of fault-finding, and of attributing the lowest motive to every action, which often caused Koorali to wince, destroying her spontaneity and self-confidence, and making her timid and reserved, and less and less a thing of flesh and blood’. Resultantly, Koorali ‘began to believe that she was really stupid and wanting in common sense, as Crichton so often told her, and that he had reasonable cause for complaint’.

Notably, these behaviours are the most prominent form of domestic violence depicted by Praed in the novel, and are judged by Praed and other characters in the text, both male and female, to be behaviours beyond reasonable patriarchal authority. It is insinuated that this form of abuse is inherently linked to other forms of domestic violence – later in the text when Koorali states that she will leave Crichton as a result of his controlling behaviour, he threatens her with legally sanctioned marital rape which is coupled with the first explicit hinting of an act of physical violence – ‘he made a gesture as if he would have fell upon her and throttled her there and then’.

The acts of verbal and psychological abuse, and what we would consider coercive control, are the key feature Praed sought to emphasise in her critique of masculine marital behaviour – her fiction, situated in the romance and domestic realist genres, generally sought to highlight the myriad forms of abuse faced by wives in colonial marriages.

These patterns of behaviours were not a new form of unacceptable marital masculine behaviour for colonial female authors such as Praed to criticise. From 1880, Ada Cambridge, a popular writer of serial fiction in Australian newspapers, detailed the systematic regime of control and abuse wives could suffer at the hands of husbands in her fiction. In Cambridge’s ‘Dinah’, serialised in The Australasian from 1879-1880, Dinah’s husband subjects her to a regime of humiliation, economic control, and psychological abuse that would be recognised today as coercive control: ‘he watched over her expenditure with a suspicious watchfulness that pounced upon every sixpence wasted; and if she tore her dress, or knocked over a wineglass, he made her life a burden to her for hours afterwards’.

As the narrator describes of Dinah’s experiences: ‘the humiliations to which she was subjected were petty, indeed, from an outside point of view – hints and slights and sneers that made no noise or scandal but they were nonetheless the cruellest that the ingenuity of an aggrieved husband, who was at once bully and coward, could devise’.

In a similar state of marital relations to Koorali and Crichton, the psychological abuse and controlling behaviour perpetrated by Dinah’s husband is the only instance of domestic violence that Cambridge explicitly details, aside from hinting at an occasion of marital rape.

By the mid 1880s then, there was certainly a growing awareness and criticism of the myriad of forms that domestic violence could take in marriages. The question of what to call this spectrum of behaviours was a difficult one – whilst ‘wife-beating’ was still the most popular term, connoting images of working class men perpetrating physical violence, courts and newspapers focused more broadly on what they termed ‘cruelty’, a legal term subjective to the discretion of individual judges. Acts that we would now consider to be economic violence, psychological abuse, and coercive control were either constructed as ‘mental cruelty’ or as constituting a broader ‘system of tyranny’ that a husband could subject his wife to.

By 1890, the New South Wales case of Hume v Hume, presided over by Justice Windeyer, court cemented ‘mental cruelty’ and a husband’s ‘system of tyranny’ as a form of domestic violence cruel enough to warrant a wife a divorce without also declaring physical violence. Edward Hume had ‘cut his wife Ellen off from the intercourse of her friends; refused to speak to her for days and weeks, except in orders’ coupled with oaths and abuse, and refused to let her leave their property’.

Yet, coercive control alone or accompanied by the ‘occasional’ blow was not enough to break the sacred bonds of marriage across the whole of Australia – Windeyer was the exception amongst his fellow judges in Victoria and Queensland. Dismissing a 1912 case in Queensland in which William Tredea had isolated his wife Laura on a rural pastoral station and controlled the amount of time she spent with her children, Justice Shand declared he had to be ‘careful not to go beyond the limits of legal cruelty’ and to not overly restrict a husband’s understood household authority.

A husband’s ‘system of tyranny’ could therefore and still was tolerated and upheld, despite growing awareness and criticism, and it wouldn’t be until the 1970s that this broader pattern of abusive behaviours would again be brought to public attention by feminists criticising domestic violence more broadly. The establishment of women’s refuges such as Elsie in 1974, alongside the testimonies of wives to the Royal Commission on Human Relationships published in 1977, put a spotlight on domestic violence, with acts of coercive control given renewed public and feminist attention. See Michelle Arrow’s The Seventies for more on this.

Yet, it has taken until 2007 for the pattern of behaviours to be given an official name and definition, and it is only in the last few years, in the wake of cases such as the murder of Hannah Clarke and the subsequent relevant of the nature of her husband’s abusive and controlling behaviour.

Why? That I can’t answer, but it is high time that we acknowledge that coercive control in Australia has been the subject of feminist and legal attention for 150 years.

As for what historians like myself can contribute to current discussions by historicising coercive control, openly acknowledging the cultural discourses and acceptability around contemporary forms of violence, and judging historical violence by current standards, allows for a revitalised and more complex understanding of domestic violence in the past – an understanding that is vital in thinking about domestic violence and coercive control in Australia and Australian society more broadly if we ever going to deal with our ‘national problem’.

The post Coercive control is not a new phenomenon appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

In her new novel, Untethered, debut author Ayesha Inoon, who is now based in Canberra, shares with readers an incredibly intimate portrait of a young Sri Lankan woman who immigrates with her husband to Australia. Here, Ayesha speaks with BroadAgenda writer, Jesse Blakers, about the book.

Untethered is a story about the complex experience of immigration but it’s also about a young woman who faces and overcomes great obstacles to find a stronger, freer version of herself. The protagonist Zia has a very sheltered and comfortable life in Sri Lanka, however she is restricted from pursuing her dreams of travel and higher education. She agrees to an arranged marriage as she knows that is what is expected of her.

In Australia she faces homesickness, isolation and poverty, however she also discovers there’s a certain freedom in being in a new country away from the cultural boundaries she’s always known.

The novel follows Zia’s journey of self-discovery, the grief of her losses and the joy of her newfound hopes and dreams.

It wasn’t so much a blending, as of drawing on my emotional experiences of immigration and navigating life in a new country to create the fictional stories of Zia and Rashid. In some ways it was easy, because I had my knowledge and experience of living in Sri Lanka, of Sri Lankan Muslim culture and life as a new immigrant in Australia.

This sometimes meant it was difficult to have distance from my characters. The initial draft was written in first person. Rewriting in third person helped give me some distance and perspective.

The pitching process was long, and sometimes disheartening. I tried to be objective about it and not take it personally when I received a rejection. There are so many factors that influence whether a book gets picked up or not, and I realised I could do little to control that beyond making sure my novel was in its best possible shape, and my submissions were well presented.

Needless to say I was thrilled to win the ASA/HQ prize and the journey from there to publication has been a dream. The team at HQ/HarperCollins have been amazingly supportive and I’ve loved working with them to launch my book into the world.

I didn’t expect the enormous amount of work that goes into producing a book – from the editing and proofreading to the cover design and marketing, there is so much that goes on behind the scenes to get books onto shelves!

I wanted to explore how gendered expectations can limit individual freedom of choice and the ability to be true to yourself.

Zia is expected to be submissive, to accept the choices of her parents in terms of what would be best for her life and to then be a ‘good wife’ to Rashid by supporting his choices. Rashid is expected to be the breadwinner and to know what is best for both himself and Zia.

We see both of them rebel against these expectations at various stages of the novel – Zia in wanting to study or work and Rashid in struggling with the fact that all the responsibility for their lives lie on him. And yet they are so confined by societal rules that they are unable to voice their true desires to each other or see how things could be different. I wanted to portray how difficult it can be to step away from such expectations and the strength it would take for someone like Zia to break free of them to follow her own path.

Cover of “Untethered.”

We all need the love and support of good friends to make it through difficult times, and I wanted Zia to have these relationships as she navigated life as a new wife and mother in Sri Lanka and then as an immigrant in Australia. In Sri Lanka, these friends are girls she grew up with and they find comfort in their shared experiences.

Her friendship with Jenny in Australia is especially poignant because although they have hardly anything in common, they enjoy each other’s company and build a strong friendship which becomes one of Zia’s foundations in Australia. Zia’s faith also evolves as she goes through her journey yet remains a constant source of comfort and strength.

It was challenging, because Zia, like many women, wanted very much to be a mother. I think there’s generations of women who were taught that this was their primary role in life and that all other ambitions were secondary, if at all. For Zia, this conditioning meant that she felt she couldn’t have more than one purpose.

Still, as you say, she never sees motherhood as a substitute because although it fulfils that desire, there are other deep needs which remain unmet, and she is left brimming with all this potential that she’s not able to express or pursue.

I would love for readers to see that Zia’s sense of purpose and her freedom, eventually came from within herself. At the beginning of the novel, she complies with all that is expected of her, believing the love and approval of her family and Rashid to be her reward, despite her secret yearnings for more out of life.

As the story progresses, Zia finds the courage to break free of her constraints and reach for independence. Although that comes at the cost of irrevocable losses, that is part of her journey, building her resilience and giving her a greater capacity to hold both the sorrows and joys of her new life.

The post Womanhood, immigration, and finding freedom appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

Pride month ended last week, and I cannot tell you how many social media posts I’ve seen reminding us in the queer community to take care of ourselves, especially in these times. As a queer person, it feels like my heart is forever sinking in my chest because another book has been banned in the US.

We may be in Australia, but we’re not as separate from America as we like to think; many of our cultural cues are imported from the US, and as I’ll explain, Australia has its share of book bans too.

Over the last two and a half years, a constant stream of new laws across the US have targeted the queer community, in particular transgender people, including access to healthcare, drag shows, and education within schools. A specific example of these sorts of attacks is book banning, which is the removal or restriction of access to certain books in schools and libraries.

While not a new phenomenon, school districts in the US have been experiencing alarmingly high rates of ‘challenges’ against a range of books, often depicting stories representing the LGBTQIA+ community, immigrants, and people of colour. The practice of ‘challenging’ a book results from an objection to the book’s content, and triggers a systematic review process to discern whether the book is deemed appropriate by librarians, teachers, and administrators.

Professor Mary Lou Rasmussen, an expert in gender, sexuality, and education from the Australian National University, believes that they can at times be politically motivated towards a certain cause. “I think that cause often involves children…and [is] about evoking children as a figure that needs to be saved.”

Professor Mary Lou Rasmussen. Picture: supplied

Many of the challenges to books have been from a minority, sometimes even a single person, lodging a complaint directly to school boards and administrators. For instance, the Florida Citizens Alliance has lodged many of the complaints in their state responsible for book bans.

Yet, their official Facebook page is followed by approximately 1.3% of Florida’s total population (3 thousand out of 22 million). Other conservative groups, such as Moms for Liberty and the Concerned Parents of the Ozarks, are no different.

Despite those small numbers, lack of access to any queer books can still affect the LGBTQIA+ community. “Books are powerful. They can teach empathy, but they can also teach self-awareness,” says queer writer and author Karis Rogerson. “I might have realised who I was sooner if I’d read a broader selection of books as a teen.” Karis isn’t the only person who struggled with a lack of diversity in books.

Trans and queer writer Robin Gow, founder and director of Transcendent Connections, released a novel in 2022 exploring the story of two transgender teens and their relationship. “With my verse novel, A Million Quiet Revolutions, I wanted to write a story I would have wanted to gift myself as a young person grappling with my gender who was without the language or resources to explain my experience.”

Just like Karis, Robin, and many other queer people, discovering queer stories changed my understanding of who I was as a teenager.

Between July and December of last year, the state of Texas banned 438 books, a 28% increase from the previous six months. This huge number of bans is partially due to books being immediately removed once challenged, despite the American Library Association and National Coalition Against Censorship recommending that challenged books should remain accessible during review. In some instances, school boards have been overwhelmed with a high number of challenges submitted together, dragging out the review processes.

We’ve seen this in Australia too. Throughout the 20th century, many literary classics, such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, were banned or restricted in Australia, often vaguely citing “obscene content” as the cause. As recently as March this year, Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer (which is also currently the book with the highest number of bans in the US) was removed from a Queensland public library after a complaint from a member of the public. Progressives have used book bans as well; two years ago, several Dr Seuss books were permanently pulled from publication due to racist stereotyping.

What makes the current book bans in the US so frustratingly painful are the type of books being banned and why.

Many of the books being challenged are accused of containing sexual content. While some do include implicit sex scenes, plenty do not. First published in 2001, Susan Meyers’ Everywhere Babies was included in the 2021 “Objectionable Materials” report (written by the Florida Citizens Alliance and often known by its inflammatory name, the “Porn in Schools” report), which listed 58 books as sexually inappropriate.

Each book in the report has a link to an individual review, requiring the reader to actively open them – and the Everywhere Babies review states that there is no ‘objectionable content’. It is listed as an LGBTQIA+ book, due to some images that show two same-sex people looking after a baby. The complete absence of sexual content in the book makes it clear that LGBTQIA+ themes have been sexualised and deemed ‘age-inappropriate’ in the report (to see a video read-through of Everywhere Babies, click here).

The popular Heartstopper books, written and illustrated by Alice Oseman, have also been challenged and banned in several school districts. The series primarily follows Nick and Charlie, two young teens navigating their feelings for each other, and later, their blossoming relationship. Having personally read these books, I can attest to the distinct lack of sexual content throughout the entire series.

I only recently reread the series, and I wholeheartedly agreed with journalist Gary Nunn when he told me that it “particularly stings” that Heartstopper has been part of the book bans. Even more so when considering that Oseman actively counteracts narratives of hypersexuality throughout the series, focusing on other aspects of Nick and Charlie’s relationship.

Nick and Charlie in the upcoming second season of Heartstopper. Picture: Netflix

“It’s rare to have such an innocent depiction of same-sex romantic affection,” continued Gary. In a previous article discussing the ambiguous grief Heartstopper stirred in him, Gary stated that Heartstopper depicts “an innocence that a whole generation of gay men like me were denied.”

So, why are we seeing books such as Heartstopper and Everywhere Babies being banned for non-existent sexual content?

PEN America’s 2023 banned books report found that of the 874 book titles banned in various US school districts between July and December last year, 26% (roughly 227) contained queer characters or themes. People of colour were also being targeted, with 30% (approximately 262) containing characters of colour or themes of race and racism.

The 2021 “Objectionable Materials” report specifically attacks same-sex parents and couples by insisting that novels portraying same-sex parents “undermine Florida Constitution that marriage is between [a] man and a woman” (Florida’s Constitution has not had its marriage section removed, first adopted in 2008, despite the legalisation of same-sex marriage back in 2015).

While some intentions behind the book bans might not be political or biased, homophobia and transphobia are, regardless, playing a large role. We all know that our teenage years can be a time of figuring out our identity, and books can be an important tool in discovering ourselves as individuals. Reading has always been a source of comfort and guidance in my life, and to think that others will not always have this opportunity is both frustrating and devastating.

“The stories we consume matter,” says author Melissa Blair. “The first way we learn is through story, and therefore the stories we read, even fictional ones, impact how we see our world.” What is just as important is the books we don’t read.

Banning and removing books that represent real people tells us that we will not be accepted as who we are, if who we are is outside of a white, heteronormative and cisnormative identity.

Professor Rasmussen, who we heard from earlier, worked in the US during the 1990’s as a queer activist. She dealt with book bans at the time. “In some ways, I think that the symbolism of the bans is more pronounced now that it was then,” Professor Rasmussen said. “LGBTQIA+ people already often feel like they’re not welcome, and these cement that.”

When discussing the impact on health and wellbeing, Professor Rasmussen voiced her concern that these book bans would “do nothing” for the mental, social, and economic wellbeing of the LGBTQIA+ community, especially young people with limited independence and choice in where they go to school. “The issues on them are compounded because of a lack of autonomy associated with the bans, which makes them all the more onerous.”

Working as a bookseller myself in a part-time job, I have witnessed the moments of joy and pride that teens especially experience when they see books that represent themselves. As a reader myself, I have come to value the experience of not only critically engaging with books, but expanding my worldview through reading. Inclusive and hopeful books such as Heartstopper are especially critical – as Gary argued, “it ought to be compulsory reading for all schools to tackle homophobia, promote equality and nourish empathy via the imagination.”

Access to a range of books, especially those reflecting our diversity, is joyful and essential. Removing that representation takes away a chance to see ourselves be understood and truly embraced, even if it’s just through fictional characters.

If you’d like a powerful reminder of why books like Heartstopper mean so much to queer viewers, Jesse Blakers wrote this piece last year.

The post Book banning: What it means for queer people appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

Who designs cities? And who are they made for? In her book, ‘Trophy Cities:’A feminist perspective on new capitals,’ Associate Professor Dorina Pojani from the University of Queensland offers a fresh perspective on socio-cultural and physical production of planned capital cities through the theoretical lens of feminism.

She evaluates the historical, spatial and symbolic manifestations of new capital cities, as well as the everyday experiences of those living there, to shed light on planning processes, outcomes and contemporary planning issues. BroadAgenda editor Ginger Gorman asked Dorina. a few quesitons.

This book evaluates the planning processes and outcomes of seven new capital cities, spread across time and cultures: Canberra, Australia; Chandigarh, India; Brasília, Brazil; Abuja, Nigeria; Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan; Naypyidaw, Myanmar; and Sejong, South Korea. I have approached my research from a feminist perspective, considering the role of gender in these cities. I am a hard critic of these dystopian megaprojects. I argue that they have been, for the most part, great planning disasters.