Early voting is underway in the primary election for two seats on the Georgia Public Service Commission, the powerful panel of regulators with final say over the rates and energy plans of the state’s largest electric utility, Georgia Power — a subsidiary of one of the largest utilities in the country.

This year’s PSC election comes with added scrutiny because it’s been nearly five years since the last one, and in that time Georgia Power bills have increased repeatedly with the current commission’s approval. It’s also the only statewide race on Georgia’s ballot this year.

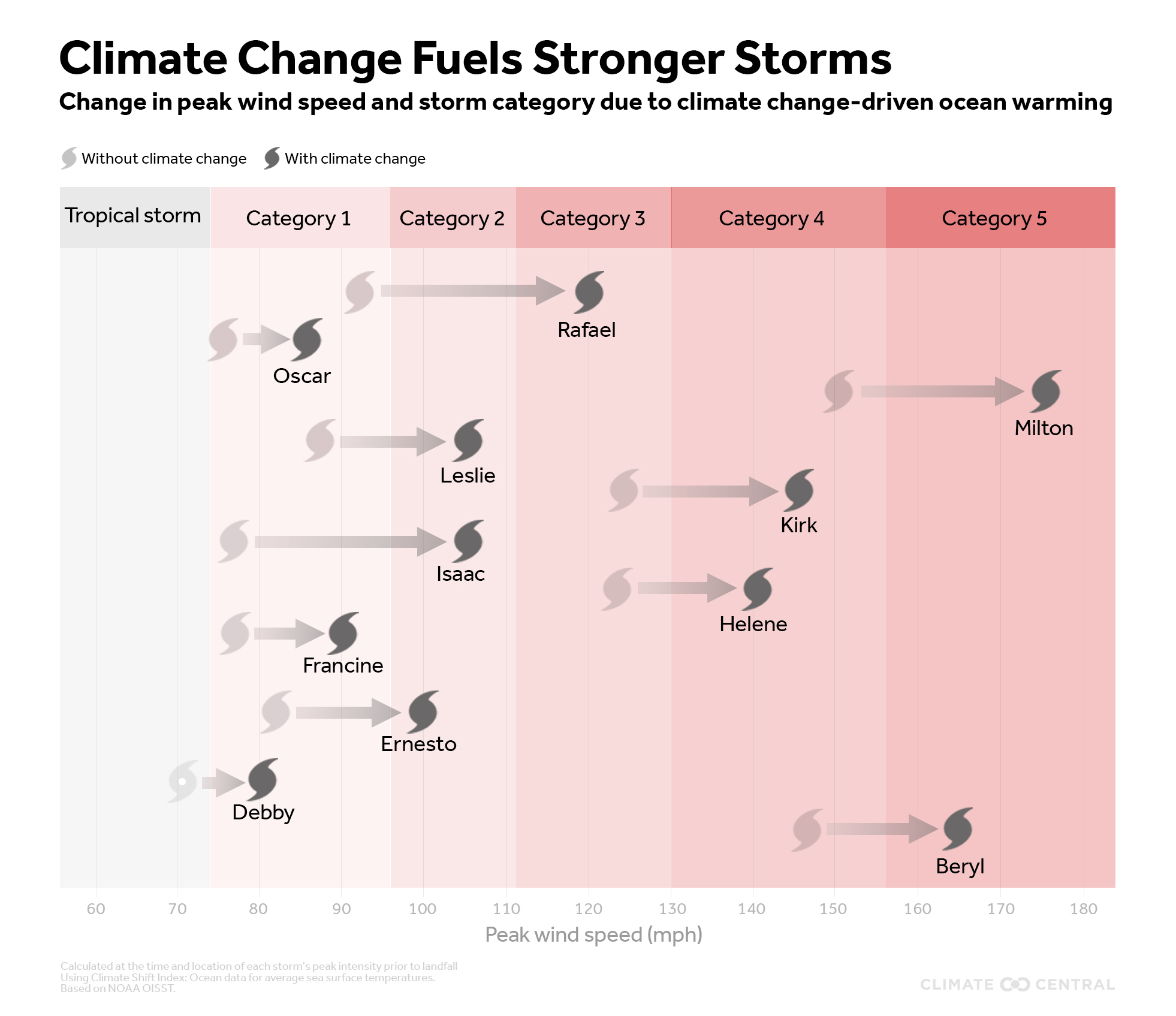

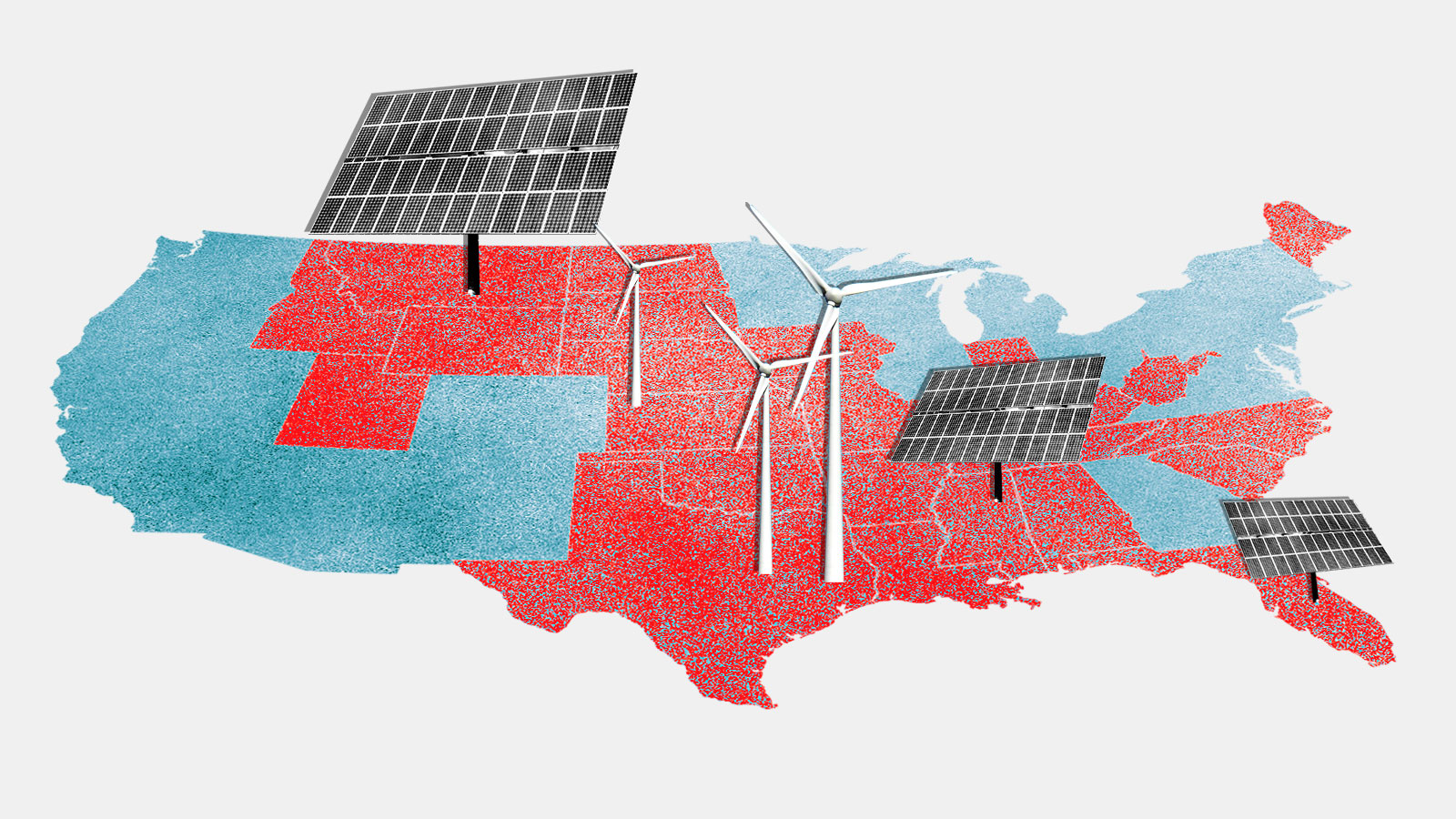

State utility commissioners across the country have a substantial impact on climate action because they oversee electric utilities and have final say over how those utilities generate energy — one of the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. In states like Georgia where monopoly utilities dominate, the commissioners’ power is magnified.

Elections for the Georgia Public Service Commission have been canceled for the last two cycles because of a voting rights lawsuit challenging the way the elections are conducted, meaning three commissioners have continued to serve and vote on key issues without facing voters as originally scheduled. Two of those commissioners, Republicans Tim Echols and Fitz Johnson, are on the ballot this year.

Candidates for the commission have to live in designated districts. This election is for district two, covering a swath of East Georgia including Augusta and Savannah, and district three, covering the three metro Atlanta counties of Clayton, Dekalb and Fulton. But all Georgia voters elect the commissioners, meaning any registered voter in Georgia can vote for both seats on the ballot, regardless of where they live.

While the incumbents running to keep their seats have touted their work on reliable energy, the new nuclear reactors at Plant Vogtle and affordable power bills, their opponents have been sharply critical of repeated rate hikes and a commission they argue doesn’t listen to the concerns of Georgians.

The candidates below are on the ballot in the June 17 primary. The winners of that election and any runoffs will then compete in the general election on November 4.

District 2

Democrats:

Alicia Johnson is running unopposed for the Democratic nomination in district two, meaning she will face the winner of the Republican primary in November. With a background in advocacy, human services and healthcare, Johnson said her chief concern is high costs for Georgians living in poverty.

“Seniors, children, single moms and working families in our communities all across 159 counties in Georgia are having to make tough decisions like whether or not they buy prescriptions or pay their electricity bills,” she said, criticizing the repeated rate hikes and Georgia Power profits approved by the current commission.

Johnson said the commission should push the utility to invest more in clean energy, including what’s known as distributed energy – rooftop solar panels and community solar – as well as battery storage and microgrids to power new industries like data centers.

She also weighed in on a proposal before the commission to temporarily freeze base power rates, which she called “a strategic move because of the special election.”

“We’re already paying some of the highest energy bills in the country,” Johnson said. “And so I see this as too little too late. We needed this kind of protection before.”

Republicans:

District two incumbent Tim Echols is perhaps the most prominent current member of the commission, known for his radio show and public appearances across the state as well as his work at the PSC. Echols cited that as one reason voters should choose him.

“Folks have come to know me as that accessible commissioner, the commissioner doing all these educational events,” he said. “So if you want me to continue with my enthusiasm and all that I put into this job in creating this great environment that we have in Georgia that attracts so much business, that’s why you should keep me.”

He also cited his work to advance solar energy in Georgia and ensure the new nuclear reactors at Plant Vogtle were completed. The state has made enormous strides on utility-scale solar energy, ranking seventh in the nation, but lags behind on battery storage, something Echols wants to change. He also said the state needs more nuclear energy, to replace closing fossil fuel plants.

Echols also touted the proposed rate freeze, which he called a “win for consumers,” though the commission has not actually adopted it yet. But he had no doubt it would.

“It will pass,” Echols said. “I can guarantee you the five Republicans will freeze rates. That is going to happen.”

Republican challenger Lee Muns took aim at Echols’s high profile in an interview with WABE.

“Well-known is a double edged sword,” he said. “Well-known means that you get judged based upon what you’ve done. And when people look at those things, what I’m hearing from a lot of them is the quality of service that they have gotten from my opponent is not what they were looking for.”

With a background in power plant construction, Muns is a strong supporter of nuclear energy. But he’s also sharply critical of how the commission handled the new reactors at Plant Vogtle, a project that came in years behind schedule and far over its original budget. Commissioners should have done more to protect Georgia Power customers from those costs, he said.

“I’m all about schedules, I’m about cost controls, I’m all about quality, I am all about safety,” Muns said. “And I want to bring all that expertise to the table.”

Because nuclear energy takes time to build, Muns said he favors natural gas and solar energy in the short term and supports phasing out coal because of the environmental risks.

District 3

Democrats:

Former Environmental Protection Agency official Daniel Blackman has run for the commission before, losing a runoff for the district four seat in January 2021 — the last time a PSC race made it past the primary.

His switch to district three this time has prompted an eligibility challenge that’s played out in court even as early voting continues. At a hearing on Tuesday, a judge said Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger was correct to disqualify Blackman from the race. Blackman could still appeal, but as it stands now, votes for him won’t count.

While he said his chief concern is high energy bills, Blackman said he would also bring critical expertise from his years working for the EPA.

“I think uniquely what is missing at the commission is a very strong and keen understanding of the energy industry,” he said. “But I’ve actually had to negotiate these deals.”

Like other candidates, Blackman was critical of the proposed rate freeze, which he said he would like to see extended for a longer period of time. He also said that Georgia Power is currently at risk of “overcommitment” to fossil fuel resources like gas and coal and should focus instead on renewables, batteries and modernizing the grid. And he said he’d like to get the public involved in utility planning.

“I’d like to work on making sure that we do community town halls around the state of Georgia to bring more ratepayers into the conversation to determine how these rates impact them on a daily basis,” Blackman said.

As the founder of Georgia Center for Energy Solutions, Peter Hubbard has intervened in PSC proceedings since 2019 and said he’s now ready to bring that expertise to a seat on the commission. His focus, he said, is on lowering energy bills and pursuing different ways of meeting Georgia’s energy needs, including solar and batteries, programs that reduce demand, rooftop solar and sharing energy capacity with neighboring utilities.

“The current commissioners accept that face value, the plan that’s provided to them by Georgia Power Company,” Hubbard said. “I have criticisms of those plans.”

Hubbard said he’d prefer to be proactive as a commissioner, seeking out possible solutions and new programs, rather than reactive to the plans put forward by Georgia Power. He also said he’s frustrated by what he sees as a lack of response from the current commissioners to constituents’ concerns about affordability and climate change.

“I see a lack of accountability among the folks at the Public Service Commission towards those residential electricity ratepayers or customers, those hardworking Georgians,” Hubbard said. “I want them to allow them to have better representation.”

Former utility analyst Robert Jones said the commission is using outdated “rules and tools” in its oversight.

“The commission has, in my opinion, been overly generous and favorable toward Georgia Power,” he said.

The current model for planning and building power resources, which passes many costs on to the utility’s customers, is a holdover from a period of slower growth, Jones said. He thinks the utility should instead have to fund its growth on the capital marketplace like other businesses.

“What the commission has been doing is really using ratepayers and small businesses as what I call interest-free subprime lenders to the utility company that is a monopoly-oriented business, profit-oriented business that’s generating excessive profits,” he said. “That’s just out of whack with the market reality of what a competitor would face.”

Jones said he also has experience working with data centers, the main driver of the current increase in energy demand, as a former executive for Microsoft. And data centers, he said, want clean energy – which he called “inconsistent” with Georgia Power’s use of fossil fuels.

Former state lawmaker and Atlanta City Council member Keisha Sean Waites declined to be interviewed for this story but answered questions via email. She said her previous experience in state and local government sets her apart because she knows “how to navigate government, write policy, and deliver results.”

As a commissioner, Waites said she would push for renewable energy and stronger benchmarks for reducing Georgia Power’s reliance on coal and natural gas. She also supports a policy called performance-based regulation, which ties a utility’s profits to performance metrics so they “only profit when they meet the needs of their customers, not just when they build expensive infrastructure,” she wrote.

“Georgians deserve a fighter at the table, someone who understands the impact rising utility bills have on everyday families,” Waites wrote. “I’m running to…bring transparency, fairness, and accountability to an agency that touches every household in this state.”

Republicans:

District three incumbent Fitz Johnson declined to be interviewed for this story. He was appointed to fill a vacancy on the commission in 2021, and the subsequent election for the remainder of his predecessor’s term was called off due to the voting rights lawsuit in 2022.

When he qualified for the race earlier this year, Johnson told WABE that the commission was “doing great work with the utilities across the state of Georgia” and called taking care of ratepayers his number one goal. He touted the new contract terms for large customers that the commission passed earlier this year as one example. Those terms are designed to protect ordinary residential and small business customers from the high costs of serving new data centers and other large power users, though some critics have questioned whether the provisions offer enough protection.

In addition to serving on the Georgia PSC, Johnson chairs a committee on natural gas planning for the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline There’s only one statewide ballot this year in Georgia — and it’s important. on Jun 12, 2025.

This post was originally published on Grist.