This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

At least 10 people have died in the devastating Los Angeles wildfires as firefighters continue to battle multiple infernos in the area. Thousands of homes and other structures have been destroyed, and some 180,000 people are under evacuation orders. Multiple neighborhoods have been completely burned down, including in the town of Altadena, where our guest, climate scientist and activist Peter Kalmus, lived until two years ago, when increasing heat and dryness pushed Kalmus to leave the Los Angeles area in fear of his safety. “I couldn’t stay there,” he says. “It’s not a new normal. … It’s a staircase to a hotter, more hellish Earth.” Kalmus discusses an op-ed he recently published in The New York Times about the decision, which he says was toned down by the paper’s editors when he attempted to explain that fossil fuel companies’ investment in climate change denial and normalization has only accelerated the pace of unprecedented large-scale climate disasters. “This is going to get worse,” he warns, “Everything has changed.”

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between BPR and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization.

After spending more than two years drafting a plan to manage and protect the nation’s old-growth forests as they endure the ravages of climate change, the Biden administration has abruptly abandoned the effort.

That decision by the U.S. Forest Service to shelve the National Old Growth Amendment ends, for now, any goal of creating a cohesive federal approach to managing the oldest trees on the 193 million acres of land it manages nationwide. Such steps will instead be taken at the local level, agency chief Randy Moore said.

“There is strong support for, and an expectation of us, to continue to conserve these forests based on the best available scientific information,” he wrote in a letter sent Tuesday to regional foresters and forest directors announcing the move. “There was also feedback that there are important place-based differences that we will need to understand in order to conserve old growth forests so they are resilient and can persist into the future, using key place-based best available scientific information based on ecological conditions on the ground.”

President Biden launched a wide-ranging effort to bolster climate resilience in the nation’s forests in an executive order he issued on Earth Day in April, 2022. In complying with the order, the Forest Service sought to bring consistency to the protection of mature and old-growth trees in the 154 forests, 20 grasslands, and other lands it manages. Such a change was warranted because the agency defines “old growth” differently in each region of the country depending on the characteristics of the local forest, but generally speaking they are at least 100 years old.

Much of the nation’s remaining ancient forests are found in places like Alaska, where some of the trees in the Tongass National Forest are more than 800 years old, and California. In the East, much old-growth is concentrated in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina. All told, old-growth forests cover about 24 million acres of the land the Forest Service manages, while mature forests cover about 67 million.

The plan would have limited logging in old-growth forests with some exceptions allowed to reduce fire risk. The Forest Service spent months gathering public comment for the proposal, which the Associated Press said was to be finalized any day now. Many scientists and advocates worried the amendment would have codified loopholes that allow logging in old-growth forests. On the other side, Republican legislators, who according to the AP introduced legislation to block any rule, and timber industry representatives argued that logging is critical to many state economies and they deserved more input into, and control over, forest management. Such criticism contributed to the decision to scuttle the plan, the AP reported.

Ron Daines, the Republican senator from Montana, issued a statement calling the Forest Service decision “a victory for commonsense local management of our forests” and said “Montana’s old growth forests are already protected by each individual forest plan, so this proposal would have simply delayed work to protect them from wildfire, which is the number one threat facing our old growth forests.”

Political disagreements over old growth conservation are not new. Jim Furnish, a former deputy director of the Forest Service who retired in 2002, said that the Forest Service has become more responsive to calls for old growth protection over the years. In the 1950s and ’60s, “they typically looked at old growth for us as the place to get the maximum quantity of wood for the highest value,” Furnish said. The debate over conservation of the spotted owl, and the 2001 Roadless Rule, helped paved the way for more dedicated protection of virgin forest, and the creation of “new” old growth through the conservation of mature second-growth forests.

Ultimately, Furnish said, the Forest Service’s failure to move quickly after Biden issued his executive order doomed the amendment. Under the Congressional Review Act, which allows lawmakers to review and potentially overturn regulations issued by federal agencies, the new Republican-controlled Congress could have killed any new regulation within 60 days, precluding any future efforts to adopt such an amendment.

Will Harlan, the Southeast director of the Center for Biological Diversity, said the plan’s death may be for the best, as old-growth protection can continue at the local level under current regulations while leaving room for future protections.

“Probably for the next few years it’s going to be a project-by-project fight, wherever the Forest Service chooses a logging project,” he said. “Advocates and conservation groups are going to be looking closely at any old growth that might be in those projects and fighting to protect them.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Biden administration axes controversial climate plan for old growth forests on Jan 9, 2025.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Katie Myers.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Raging wildfires continue to scorch communities across the Los Angeles area, killing at least five people, displacing about 100,000 more and destroying thousands of structures. With firefighters unable to contain much of the blaze, the toll is expected to rise. The wildfires that started Tuesday caught much of the city by surprise, quickly growing into one of the worst fire disasters in Los Angeles history. Mayor Karen Bass and the City Council have come under criticism for cutting the fire department’s budget by around 2% last year while the police department saw a funding increase. Nearly 400 incarcerated firefighters are among those who have been deployed to battle the fires. Journalist Sonali Kolhatkar, who evacuated her home to flee the destruction, says it has been “frustrating” to watch the corporate media’s coverage of the fires. “No one is talking about climate change in the media,” she says. We also speak with journalist John Vaillant, author of Fire Weather: On the Front Lines of a Burning World, who says the L.A. wildfires should be a wake-up call. “This blind — frankly, suicidal — loyalty to the status quo of keeping fossil fuels preeminent in our energy system is creating an increasingly difficult situation and unlivable situation,” says Vaillant.

This content originally appeared on Democracy Now! and was authored by Democracy Now!.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Harel Dor and Finn O’Brien were just finishing up dinner at a restaurant in Pasadena, California on Tuesday evening, when a friend texted them about an evacuation warning. A severe windstorm had spread what became the Eaton fire to the hills behind their home.

“Driving back up the house it was already feeling apocalyptic, with downed trees and visibility getting worse,” Dor said. As the couple returned to the house to evacuate their two cats, they could see the flames in the distance. Dor, who works nearby at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says while some coworkers have lost their homes, they don’t know if their apartment has survived the blaze.

“The emotions haven’t arrived yet,” Dor said. “A lot of it is just numbness and shock at the events unfolding.”

The hills around Los Angeles have become an inferno. Days after forecasters warned of dangerous fire weather conditions, twin blazes — driven by 100 mile per hour winds — began raging across some of Southern California’s most expensive neighborhoods, sending thousands of residents fleeing and threatening historic sites. Within five hours on Wednesday morning, both the Palisades Fire east of Santa Monica and the Eaton Fire across Pasadena exploded from 2,000 acres to over 10,000. So far, two people have been confirmed dead and more than 1,000 structures have burned, potentially making the Palisades Fire one of the country’s most destructive.

“I do expect it is plausible that the Palisades Fire in particular will become the costliest on record, period,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, during a livestream on Wednesday morning. That’s partly due to “the fact that some of those structures are some of the most expensive homes and buildings in the world.”

The fires have both immediate and underlying causes. The first ingredient for making such monstrous wildfires is the fuel. In the previous two years, some parts of coastal Southern California experienced their two wettest winters on record, spurring the growth of grass and brush. But now the region has had its driest start of winter on record, which parched that vegetation. The chaparral landscape turned into abundant tinder just waiting to burn.

“Under conditions of climate change, we will have wetter wet periods, very wet wet periods, and very dry dry periods,” said Stephanie Pincetl, director of the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA. “The climatic conditions that Southern California has experienced over centuries are simply going to be exacerbated.”

The second ingredient is the spark. It will take some time for investigators to determine what set off all these blazes, but where humans tread, wildfires start. It could be a wayward firework, or a chain dragging off the back of a truck on the highway, or arson. California also has a major problem with its electric equipment jostling in the wind, showering sparks into the vegetation below. As winds kicked up on Tuesday, utilities like Southern California Edison shut off power to areas of the city in an effort to prevent just such an event.

The third ingredient was high winds. This is Southern California’s prime season for Santa Ana winds, which form in the interior of the western United States. As that warm, dry air moves toward the sea, it drops down mountains, picking up speed. Scientists don’t expect climate change to boost the speed of these Santa Ana winds, though they may get drier and hotter. “They can dry vegetation even more,” said Alexander Gershunov, a research meteorologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “The same slopes that get a lot of precipitation from atmospheric rivers also get the strong Santa Ana winds.”

So there’s more fuel in those places, and unfortunately more of the wind that drives catastrophic fires. Once there’s a spark, the winds shove the fire forward with oftentimes inescapable speed. That’s how the Camp Fire killed 85 people in 2018, as the flames raced through the town of Paradise, trapping people in homes and cars. And that’s why authorities are fearing for the worst for these new, fast-moving Los Angeles fires.

“The spread has been quite dramatic. The Eaton fire especially,” said Devin Black, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service. Because the winds are moving erratically, he said, the public should be cautious when driving around the flames. “They can move very quickly, and you might get trapped,” he said.

Wind-driven wildfires are also notoriously difficult to fight, and not just because they move so fast. Those Santa Ana winds are blowing embers ahead of the main wall of the fire, lighting new fires perhaps a mile ahead. So a large, intense fire can spawn smaller blazes that themselves burn out of control, as crews are already stretched thin across the landscape. In Los Angeles county on Wednesday afternoon, four separate fires were taxing the firefighting response, with some fire hydrants running dry. None of them were contained, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Part of the problem is that winds grounded the aircraft used to drop water.

The immediate emergency is containing the blazes and getting people to safety. The longer-term challenge is better adapting Los Angeles, and the rest of California, to a future of ever-worsening droughts and wildfires. “People talk about adapting to the climate,” Pincetl said. “We haven’t adapted to the climate we have, let alone the climate that’s coming.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why Los Angeles is burning in January on Jan 8, 2025.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Navigating the shared challenges of climate change, geostrategic tensions, political upheaval, disaster recovery and decolonisation plus a 50th birthday party, reports a BenarNews contributor’s analysis.

COMMENTARY: By Tess Newton Cain

Vanuatu’s devastating earthquake and dramatic political developments in Tonga and New Caledonia at the end of 2024 set the tone for the coming year in the Pacific.

The incoming Trump administration adds another level of uncertainty, ranging from the geostrategic competition with China and the region’s resulting militarisation through to the U.S. response to climate change.

And decolonisation for a number of territories in the Pacific will remain in focus as the region’s largest country celebrates its 50th anniversary of independence.

The deadly 7.3 earthquake that struck Port Vila on December 17 has left Vanuatu reeling. As the country moves from response to recovery, the full impacts of the damage will come to light.

The economic hit will be significant, with some businesses announcing that they will not open until well into the New Year or later.

Amid the physical carnage there’s Vanuatu’s political turmoil, with a snap general election triggered in November before the disaster struck to go ahead on January 16.

On Christmas Eve a new prime minister was elected in Tonga. ‘Aisake Valu Eke is a veteran politician, who has previously served as Minister of Finance. He succeeded Siaosi Sovaleni who resigned suddenly after a prolonged period of tension between his office and the Tongan royal family.

Eke takes the reins as Tonga heads towards national elections, due before the end of November. He will likely want to keep things stable and low key between now and then.

Fall of New Caledonia government

In Kanaky New Caledonia, the resignation of the Calédonie Ensemble party — also on Christmas Eve — led to the fall of the French territory’s government.

After last year’s violence and civil disorder – that crippled the economy but stopped a controversial electoral reform — the political turmoil jeopardises about US$77 million (75 million euro) of a US$237 million recovery funding package from France.

In addition, and given the fall of the Barnier government in Paris, attempts to reach a workable political settlement in New Caledonia are likely to be severely hampered, including any further movement to secure independence.

In France’s other Pacific territory, the government of French Polynesia is expected to step up its campaign for decolonisation from the European power.

Possibly the biggest party in the Pacific in 2025 will be the 50th anniversary of Papua New Guinea’s independence from Australia, accompanied hopefully by some reflection and action about the country’s future.

Eagerly awaited also will be the data from the country’s flawed census last year, due for release on the same day — September 16. But the celebrations will also serve as a reminder of unfinished self-determination business, with its Autonomous Region of Bougainville preparing for their independence declaration in the next two years.

The shadow of geopolitics looms large in the Pacific islands region. There is no reason to think that will change this year.

Trump administration unkowns

A significant unknown is how the incoming Trump administration will alter policy and funding settings, if at all. The current (re)engagement by the US in the region started with Trump during his first incumbency. His 2019 meeting with the then leaders of the compact states — Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, Republic of Marshall Islands — at the White House was a pivotal moment.

Under Biden, billions of dollars have been committed to “securitise” the region in response to China. This year, we expect to see US marines start to transfer in numbers from Okinawa to Guam.

However, given Trump’s history and rhetoric when it comes to climate change, there is some concern about how reliable an ally the US will be when it comes to this vital security challenge for the region.

The last time Trump entered the White House, he withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement and he is widely expected to do the same again this time around.

In addition to polls in Tonga and Vanuatu, elections will be held in the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, New Caledonia and for the Autonomous Bougainville Government.

There will also be a federal election in Australia, the biggest aid donor in the Pacific, and a change in government will almost certainly have impacts in the region.

Given the sway that the national security community has on both sides of Australian politics, the centrality of Pacific engagement to foreign policy, particularly in response to China, is unlikely to change.

Likely climate policy change

How that manifests could look quite different under a conservative Liberal/National party government. The most likely change is in climate policy, including an avowed commitment to invest in nuclear power.

A refusal to shift away from fossil fuels or commit to enhanced finance for adaptation by a new administration could reignite tensions within the Pacific Islands Forum that have, to some extent, been quietened under Labor’s Albanese government.

Who is in government could also impact on the bid to host COP31 in 2026, with a decision between candidates Turkey and Australia not due until June, after the poll.

Pacific leaders and advocates face a systemic challenge regarding climate change. With the rise in conflict and geopolitical competition, the global focus on the climate crisis has weakened. The prevailing sense of disappointment over COP29 last year is likely to continue as partners’ engagement becomes increasingly securitised.

A major global event for this year is the Oceans Summit which will be held in Nice, France, in June. This is a critical forum for Pacific countries to take their climate diplomacy to a new level and attack the problem at its core.

In 2023, the G20 countries were responsible for 76 percent of global emissions. By capitalising on the geopolitical moment, the Pacific could nudge the key players to greater ambition.

Several G20 countries are seeking to expand and deepen their influence in the region alongside the five largest emitters — China, US, India, Russia, and Japan — all of which have strategic interests in the Pacific.

Given the increasingly transactional nature of Pacific engagement, 2025 should present an opportunity for Pacific governments to leverage their geostrategic capital in ways that will address human security for their peoples.

Dr Tess Newton Cain is a principal consultant at Sustineo P/L and adjunct associate professor at the Griffith Asia Institute. She is a former lecturer at the University of the South Pacific and has over 25 years of experience working in the Pacific islands region. The views expressed here are hers, not those of BenarNews/RFA. Republished from BenarNews with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

COMMENTARY: By David Robie, editor of Asia Pacific Report

With the door now shut on 2024, many will heave a sigh of relief and hope for better things this year.

Decolonisation issues involving the future of Kanaky New Caledonia and West Papua – and also in the Middle East with controversial United Nations votes by some Pacific nations in the middle of a livestreamed genocide — figured high on the agenda in the past year along with the global climate crisis and inadequate funding rescue packages.

Asia Pacific Report looks at some of the issues and developments during the year that were regarded by critics as betrayals:

1. Fiji and PNG ‘betrayal’ UN votes over Palestine

Just two weeks before Christmas, the UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to demand an immediate ceasefire in the Gaza Strip under attack from Israel — but three of the isolated nine countries that voted against were Pacific island states, including Papua New Guinea.

The assembly passed a resolution on December 11 demanding an immediate, unconditional and permanent ceasefire in Gaza, which was adopted with 158 votes in favour from the 193-member assembly and nine votes against with 13 abstentions.

Of the nine countries voting against, the three Pacific nations that sided with Israel and its relentless backer United States were Nauru, Papua New Guinea and Tonga.

The other countries that voted against were Argentina, Czech Republic, Hungary and Paraguay.

Thirteen abstentions included Fiji, which had previously controversially voted with Israel, Micronesia, and Palau. Supporters of the resolution in the Pacific region included Australia, New Zealand, and Timor-Leste.

Ironically, it was announced a day before the UNGA vote that the United States will spend more than US$864 million (3.5 billion kina) on infrastructure and military training in Papua New Guinea over 10 years under a defence deal signed between the two nations in 2023, according to PNG’s Foreign Minister Justin Tkatchenko.

Any connection? Your guess is as good as mine. Certainly it is very revealing how realpolitik is playing out in the region with an “Indo-Pacific buffer” against China.

However, the deal actually originated almost two years earlier, in May 2023, with the size of the package reflecting a growing US security engagement with Pacific island nations as it seeks to counter China’s inroads in the vast ocean region.

Noted BenarNews, a US soft power news service in the region, the planned investment is part of a defence cooperation agreement granting the US military “unimpeded access” to develop and deploy forces from six ports and airports, including Lombrum Naval Base.

Two months before PNG’s vote, the UNGA overwhelmingly passed a resolution demanding that the Israeli government end its occupation of Palestinian territories within 12 months — but half of the 14 countries that voted against were from the Pacific.

Affirming an International Court of Justice (ICJ) opinion requested by the UN that deemed the decades-long occupation unlawful, the opposition from seven Pacific nations further marginalised the island region from world opinion against Israel.

Several UN experts and officials warned against Israel becoming a global “pariah” state over its 15 month genocidal war on Gaza.

The final vote tally was 124 member states in favour and 14 against, with 43 nations abstaining. The Pacific countries that voted with Israel and its main ally and arms-supplier United States against the Palestinian resolution were Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Palau, Tonga and Tuvalu.

In February, Fiji faced widespread condemnation after it joined the US as one of the only two countries — branded as the “outliers” — to support Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territory in an UNGA vote over an International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion over Israel’s policies in the occupied territories.

Condemning the US and Fiji, Palestinian Foreign Minister Riyad al-Maliki declared: “Ending Israel’s impunity is a moral, political and legal imperative.”

Fiji’s envoy at the UN, retired Colonel Filipo Tarakinikini, defended the country’s stance, saying the court “fails to take account of the complexity of this dispute, and misrepresents the legal, historical, and political context”.

However, Fiji NGOs condemned the Fiji vote as supporting “settler colonialism” and long-standing Fijian diplomats such as Kaliopate Tavola and Robin Nair said Fiji had crossed the line by breaking with its established foreign policy of “friends-to-all-and-enemies-to-none”.

2. West Papuan self-determination left in limbo

For the past decade, Pacific Island Forum countries have been trying to get a fact-finding human mission deployed to West Papua. But they have encountered zero progress with continuous roadblocks being placed by Jakarta.

This year was no different in spite of the appointment of Fiji and Papua New Guinea’s prime ministers to negotiate such a visit.

Pacific leaders have asked for the UN’s involvement over reported abuses as the Indonesian military continues its battles with West Papuan independence fighters.

A highly critical UN Human Right Committee report on Indonesia released in May highlighted “systematic reports about the use of torture” and “extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances of Indigenous Papuan people”.

But the situation is worse now since President Prabowo Subianto, the former general who has a cloud of human rights violations hanging over his head, took office in October.

Fiji’s Sitiveni Rabuka and Papua New Guinea’s James Marape were appointed by the Melanesian Spearhead Group in 2023 as special envoys to push for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ visit directly with Indonesia’s president.

Prabowo taking up the top job in Jakarta has filled West Papuan advocates and activists with dread as this is seen as marking a return of “the ghost of Suharto” because of his history of alleged atrocities in West Papua, and also in Timor-Leste before independence.

Already Prabowo’s acts since becoming president with restoring the controversial transmigration policies, reinforcing and intensifying the military occupation, fuelling an aggressive “anti-environment” development strategy, have heralded a new “regime of brutality”.

And Marape and Rabuka, who pledged to exiled indigenous leader Benny Wenda in Suva in February 2023 that he would support the Papuans “because they are Melanesians”, have been accused of failing the West Papuan cause.

3. France rolls back almost four decades of decolonisation progress

When pro-independence protests erupted into violent rioting in Kanaky New Caledonia on May 13, creating havoc and destruction in the capital of Nouméa and across the French Pacific territory with 14 people dead, intransigent French policies were blamed for having betrayed Kanak aspirations for independence.

I was quoted at the time by The New Zealand Herald and RNZ Pacific of blaming France for having “lost the plot” since 2020.

While acknowledging the goodwill and progress that had been made since the 1988 Matignon accords and the Nouméa pact a decade later following the bloody 1980s insurrection, the French government lost the self-determination trajectory after two narrowly defeated independence referendums and a third vote boycotted by Kanaks because of the covid pandemic.

This third vote with less than half the electorate taking part had no credibility, but Paris insisted on bulldozing constitutional electoral changes that would have severely disenfranchised the indigenous vote. More than 36 years of constructive progress had been wiped out.

“It’s really three decades of hard work by a lot of people to build, sort of like a future for Kanaky New Caledonia, which is part of the Pacific rather than part of France,” I was quoted as saying.

France had had three prime ministers since 2020 and none of them seemed to have any “real affinity” for indigenous issues, particularly in the South Pacific, in contrast to some previous leaders.

In the wake of a snap general election in mainland France, when President Emmanuel Macron lost his centrist mandate and is now squeezed between the polarised far right National Rally and the left coalition New Popular Front, the controversial electoral reform was quietly scrapped.

New French Overseas Minister Manual Valls has heralded a new era of negotiation over self-determination. In November, he criticised Macron’s “stubbornness’ in an interview with the French national daily Le Parisien, blaming him for “ruining 36 years of dialogue, of progress”.

But New Caledonia is not the only headache for France while pushing for its own version of an “Indo-Pacific” strategy. Pro-independence French Polynesian President Moetai Brotherson and civil society leaders have called on the UN to bring Paris to negotiations over a timetable for decolonisation.

Kanaks and the Pacific’s pro-decolonisation activists had hoped that an intervention by the Pacific Islands Forum in support of the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS) would enhance their self-determination stocks.

However, they were disappointed. And their own internal political divisions have not made things any easier.

On the eve of the three-day fact-finding delegation to the territory in October, Fiji’s Rabuka was already warning the local government (led by pro-independence Louis Mapou to “be reasonable” in its demands from Paris.

In other words, back off on the independence demands. Rabuka was quoted by RNZ Pacific reporter Lydia Lewis as saying, “look, don’t slap the hand that has fed you”.

Rabuka and Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown and then Tongan counterpart Hu’akavameiliku Siaosi Sovaleni visited the French territory not to “interfere” but to “lower the temperature”.

But an Australian proposal for a peacekeeping force under the Australian-backed Pacific Policing Initiative (PPI) fell flat, and the mission was generally considered a failure for Kanak indigenous aspirations.

5. Climate crisis — the real issue and geopolitics

In spite of the geopolitical pressures from countries, such as the US, Australia and France, in the region in the face of growing Chinese influence, the real issue for the Pacific remains climate crisis and what to do about it.

Controversy marked an A$140 million aid pact signed between Australia and Nauru last month in what was being touted as a key example of the geopolitical tightrope being forced on vulnerable Pacific countries.

This agreement offers Nauru direct budgetary support, banking services and assistance with policing and security. The strings attached? Australia has been granted the right to veto any agreement with a third country such as China.

Critics have compared this power of veto to another agreement signed between Australia and Tuvalu in 2023 which provided Australian residency opportunities and support for climate mitigation. However, in return Australia was handed guarantees over security.

The previous month, November, was another disappointment for the Pacific when it was “once again ignored” at the UN COP29 climate summit in the capital Baku of oil and natural gas-rich Azerbaijan.

The Suva-based Pacific Islands Climate Action Network (PICAN) condemned the outcomes as another betrayal, saying that the “richest nations turned their backs on their legal and moral obligations” at what had been billed as the “finance COP”.

The new climate finance pledge of a US$300 billion annual target by 2035 for the global fight against climate change was well short of the requested US$1 trillion in aid.

Climate campaigners and activist groups branded it as a “shameful failure of leadership” that forced Pacific nations to accept the “token pledge” to prevent the negotiations from collapsing.

Much depends on a climate justice breakthrough with Vanuatu’s landmark case before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) arguing that those harming the climate are breaking international law.

The case seeks an advisory opinion from the court on the legal responsibilities of countries over the climate crisis, and many nations in support of Vanuatu made oral submissions last month and are now awaiting adjudication.

Given the primacy of climate crisis and vital need for funding for adaptation, mitigation and loss and damage faced by vulnerable Pacific countries, former Pacific Islands Forum Secretary-General Meg Taylor delivered a warning:

“Pacific leaders are being side-lined in major geopolitical decisions affecting their region and they need to start raising their voices for the sake of their citizens.”

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

At any given moment, crude oil is being pumped up from the depths of the planet. Some of that sludge gets sent to a refinery and processed into plastic, then it becomes the phone in your hand, the shades on your window, the ornaments hanging from your Christmas tree.

Although scientists know how much carbon dioxide is emitted to make these products (a new iPhone is akin to driving more than 200 miles), there’s little research into how much gets stashed away in them. A study published on Friday in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability estimates that billions of tons of carbon from fossil fuels — coal, oil, and gas — was stored in gadgets, building materials, and other long-lasting human-made items over a recent 25 year period, tucked away in what the researchers call the “technosphere.”

According to the study by researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, 400 million tons of carbon gets added to the technosphere’s stockpile every year, growing at a slightly faster rate than fossil fuel emissions. But in many cases, the technosphere doesn’t keep that carbon permanently; if objects get thrown away and incinerated, they wind up warming the atmosphere, too. In 2011, 9 percent of all extracted fossil carbon was sunk into items and infrastructure in the technosphere, an amount that would almost equal that year’s emissions from the European Union if it were burned.

“It’s like a ticking time bomb,” said Klaus Hubacek, an ecological economist at the University of Groningen and senior author of the paper. “We draw lots of fossil resources out of the ground and put them in the technosphere and then leave them sitting around. But what happens after an object’s lifetime?”

The word “technosphere” got its start in 1960, when a science writer named Wil Lepkowski wrote that “modern man has become a goalless, lonely prisoner of his technosphere,” in an article for the journal Science. Since then, the term, a play on “biosphere,” has been used by ecologists and geologists to grapple with the amount of stuff humankind has smothered the planet in.

“The problem is that we have been incredibly wasteful as we’ve been making and building things.” said Jan Zalasiewicz, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the University of Groningen study.

In 2016, Zalasiewicz and his colleagues published a paper that estimated the technosphere had grown to approximately 30 trillion tonnes, an amount 100,000 times greater than the mass of all humans piled on top of each other. The paper also found that the number of “technofossils” — unique kinds of manmade objects — outnumbered the number of unique species of life on the planet. In 2020, a separate group of researchers found that the technosphere doubles in volume roughly every 20 years and now likely outweighs all living things.

“The question is, how does the technosphere impinge upon the biosphere?” Zalasiewicz said. Plastic bags and fishing nets, for example, can choke the animals that encounter them. And unlike natural ecosystems, like forests and oceans that can absorb carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, humans are “not very good at recycling,” Zalasiewicz said.

Managing the disposal of all this stuff in a more climate-friendly way is precisely the problem that the researchers from University of Groningen want to draw attention to. Their research looked at the 8.4 billion tons of fossil carbon in human-made objects that were in use for at least a year between 1995 and 2019. Nearly 30 percent of this carbon was trapped in rubber and plastic, much of it in household appliances, and another quarter was stashed in bitumen, a byproduct of crude oil used in construction.

“Once you discard these things, the question is, how do you treat that carbon?” said Kaan Hidiroglu, one of the study’s authors and an energy and environmental studies PhD student at the University of Groningen. “If you put it into incinerators and burn it, you immediately release more carbon emissions into the atmosphere, which is something we really do not want to do.”

Each year, the paper estimates, roughly a third of these fossil-products in the technosphere get incinerated. Another third end up in landfills, which can act as a kind of long-term carbon sink. But unfortunately, the authors acknowledge, these sites often leach chemicals, burp out methane, or shed microplastics into the environment. A little less than a third is recycled — a solution that comes with its own problems — and a small amount is littered.

“There’s so many different aspects to the problem and treating it properly,” Hubacek said. Nevertheless, he said, landfills are a good starting point if managed well. According to the study, the bulk of fossil carbon that’s put into landfills decays slowly and stays put over 50 years. Designing products in a way that allows them to be recycled and last a long time can help keep the carbon trapped for longer.

Ultimately, Hubacek said, the real solution starts with people questioning if they really need so much stuff. “Reduce consumption and avoid making it in the first place. But once you have it, that’s when we need to think about what to do next.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Your gadgets are actually carbon sinks — for now on Dec 20, 2024.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

With just a month left in office, the Biden administration is setting a bold new target for U.S. climate action. On Thursday, the White House announced a national goal that would see the country’s greenhouse gas emissions drop 61 to 66 percent below 2005 levels by 2035. That would keep the United States on a “straight line” trajectory toward Biden’s ultimate goal of hitting net zero emissions by 2050, officials said. If that happens, it would mean the country is only emitting as much carbon as it’s simultaneously sequestering through techniques like restoring forests and wetlands — in other words, that it’s no longer playing any part in warming the planet.

The announcement is the latest in a series of climate-related actions Biden is taking during his final months in office. In the last week alone, his administration pushed for an international deal to limit global fossil fuel finance and published a study that cautioned against new export infrastructure for liquefied natural gas. These actions are designed to shore up environmental action ahead of president-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration in January.

Just as he did during his first term, Trump is promising to boost fossil fuels when he takes office next year. He’s also pledged to claw back funding from Biden’s landmark climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, which provides billions of dollars in subsidies and tax breaks to supercharge renewable energy adoption, and to once again pull the United States out of the landmark Paris climate agreement, the 2015 United Nations accord intended to limit global warming to under 2 degrees Celsius compared to preindustrial levels. (That withdrawal process took years when Trump first tried it, but it will likely move much faster this time.)

“The Biden-Harris administration may be about to leave office, but we’re confident in America’s ability to rally around this new climate program,” said John Podesta, the administration’s senior climate advisor, on a call with reporters. “While the United States federal government under President Trump may put climate action on the back burner, the work to contain climate change is going to continue in the United States with commitment and passion and belief.”

Podesta maintained that the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, and other federal policies have created enough momentum that emissions will continue to decline without further federal encouragement. He noted that the private sector has announced $450 billion in investments in clean energy projects over the past four years, much of which was stimulated by the IRA, and more investment is likely to follow even under Trump’s tenure. A study from Princeton University found that the law will be enough to reduce U.S. emissions by as much as 48 percent by 2035 — a good portion of the way toward the new goal, but not all the way there.

Much of the work will fall on states, who regulate their own utilities and can promote the switch to renewable energy sources. Cities run their own public transportation systems and set energy-efficiency building codes. Governors and mayors have long collaborated on more ambitious goals than the federal government, even under Democratic administrations.

“Across the country,” White House National Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi said in the press call Wednesday, “we see decarbonization efforts to reduce our emissions in many ways achieving escape velocity, an inexorable path, a place from which we will not turn back.”

A wide coalition of governors, mayors, tribes, and companies has pledged to continue climate progress over the next four years under Trump, and more than 200 of these entities have laid out their own climate plans. They can attempt their own decarbonization efforts, as New York state plans to do through its new congesting pricing policy in Manhattan, or by litigating against Trump’s emissions-boosting policies, as California Governor Gavin Newsom has said he plans to do.

Fundamental market forces are also at work. The prices of renewables like solar panels and wind turbines, plus the batteries to store that energy, have been plummeting. That’s partly why Texas — not exactly a bastion of climate action — now generates more renewable energy than any other state. And heat pumps — which move heat into a home using electricity instead of fossil fuels — now outsell gas furnaces in the U.S.

“Pioneering offshore wind farms are delivering clean power,” Zaidi said. “Retired nuclear plants are coming back online. America is racing forward on solar and batteries. Not just the deployment, but also the means to stamp those products ‘Made in America.’”

The new plan places particular emphasis on efforts to reduce emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that warms the earth around 80 times as fast as carbon dioxide but lingers in the atmosphere for a shorter time period. Biden has rolled out regulations designed to penalize the huge share of methane emissions that come from the oil and gas sector, a move that even ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods has asked Trump not to repeal. Last month, at the United Nations’ international climate meeting, COP29, the U.S. announced a partnership with China to track methane leakage from oil infrastructure and develop technologies to mitigate it. The administration said it expects methane emissions to fall by 35 percent over the next decade if the nation meets its broader climate target.

The United States is submitting its new target as part of its requirements under the Paris Agreement. The treaty calls on every country to outline its climate ambitions every five years in documents known as “nationally determined contributions,” or NDCs. When he took office in 2021, Biden set a national pledge to reduce the country’s greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. The new 61-66 percent target for 2035 puts the U.S. in the middle of the pack when it comes to this round of Paris climate plans, which are due from all countries in February. The United Kingdom announced a much more ambitious 81 percent reduction target at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, last month, while the United Arab Emirates has only committed to a 47 percent reduction over the same period. Brazil, which is hosting COP30 next year, has a goal that is similar to Biden’s.

Some advocacy organizations chastised Biden for not setting an even more ambitious target, one in line with that of the United Kingdom.

“With a climate denier about to enter the White House, the Biden administration’s new national climate plan represents the bare minimum floor for climate action,” said Ashfaq Khalfan, the climate justice director at Oxfam America, the U.S. chapter of the global anti-poverty advocacy organization. “It falls far short of the U.S.’s fair share of emissions reduction as the world’s largest historical polluter.”

But others praised Biden for trying to ratchet up climate ambition despite the dark short-term outlook. Rachel Cleetus, the climate policy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said other nations would appreciate that the outgoing government had set a realistic target for the nation’s climate ambition.

“I think the international community will welcome the U.S. showing it understands the importance of doing its part to meet global climate goals,” she said. “There will be challenges, for sure, but what’s not reasonable is letting political winds dictate the future of the planet and the safety of people now and for generations to come.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Biden just set a big new climate goal. Can the U.S. achieve it? on Dec 19, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

ANALYSIS: By Sione Tekiteki, Auckland University of Technology

The A$140 million aid agreement between Australia and Nauru signed last week is a prime example of the geopolitical tightrope vulnerable Pacific nations are walking in the 21st century.

The deal provides Nauru with direct budgetary support, stable banking services, and policing and security resources. In return, Australia will have the right to veto any pact Nauru might make with other countries — namely China.

The veto terms are similar to the “Falepili Union” between Australia and Tuvalu signed late last year, which granted Tuvaluans access to Australian residency and climate mitigation support, in exchange for security guarantees.

And just last week, more details emerged about a defence deal between the United States and Papua New Guinea, now revealed to be worth US$864 million.

In exchange for investment in military infrastructure development, training and equipment, the US gains unrestricted access to six ports and airports.

Also last week, PNG signed a 10-year, A$600 million deal to fund its own team in Australia’s NRL competition. In return, “PNG will not sign a security deal that could allow Chinese police or military forces to be based in the Pacific nation”.

These arrangements are all emblematic of the geopolitical tussle playing out in the Pacific between China and the US and its allies.

This strategic competition is often framed in mainstream media and political commentary as an extension of “the great game” played by rival powers. From a traditional security perspective, Pacific nations can be depicted as seeking advantage to leverage their own development priorities.

But this assumption that Pacific governments are “diplomatic price setters”, able to play China and the US off against each other, overlooks the very real power imbalances involved.

The risk, as the authors of one recent study argued, is that the “China threat” narrative becomes the justification for “greater Western militarisation and economic dominance”. In other words, Pacific nations become diplomatic price takers.

Defence diplomacy

Pacific nations are vulnerable on several fronts: most have a low economic base and many are facing a debt crisis. At the same time, they are on the front line of climate change and rising sea levels.

The costs of recovering from more frequent extreme weather events create a vicious cycle of more debt and greater vulnerability. As was reported at this year’s United Nations COP29 summit, climate financing in the Pacific is mostly in the form of concessional loans.

The Pacific is already one of the world’s most aid-reliant regions. But considerable doubt has been expressed about the effectiveness of that aid when recipient countries still struggle to meet development goals.

At the country level, government systems often lack the capacity to manage increasing aid packages, and struggle with the diplomatic engagement and other obligations demanded by the new geopolitical conditions.

In August, Kiribati even closed its borders to diplomats until 2025 to allow the new government “breathing space” to attend to domestic affairs.

In the past, Australia championed governance and institutional support as part of its financial aid. But a lot of development assistance is now skewed towards policing and defence.

Australia recently committed A$400 million to the Pacific Policing Initiative, on top of a host of other security-related initiatives. This is all part of an overall rise in so-called “defence diplomacy”, leading some observers to criticise the politicisation of aid at the expense of the Pacific’s most vulnerable people.

Lack of good faith

At the same time, many political parties in Pacific nations operate quite informally and lack comprehensive policy manifestos. Most governments lack a parliamentary subcommittee that scrutinises foreign policy.

The upshot is that foreign policy and security arrangements can be driven by personalities rather than policy priorities, with little scrutiny. Pacific nations are also susceptible to corruption, as highlighted in Transparency International’s 2024 Annual Corruption Report.

Writing about the consequences of the geopolitical rivalry in the Solomon Islands, Transparency Solomon Islands executive director Ruth Liloqula wrote:

Since 2019, my country has become a hotbed for diplomatic tensions and foreign interference, and undue influence.

Similarly, Pacific affairs expert Distinguished Professor Steven Ratuva has argued the Australia–Tuvalu agreement was one-sided and showed a “lack of good faith”.

Behind these developments, of course, lies the evolving AUKUS security pact between Australia, the US and United Kingdom, a response to growing Chinese presence and influence in the “Indo-Pacific” region.

The response from Pacific nations has been diplomatic, perhaps from a sense they cannot “rock the submarine” too much, given their ties to the big powers involved. But former Pacific Islands Forum Secretary-General Meg Taylor has warned:

Pacific leaders were being sidelined in major geopolitical decisions affecting their region and they need to start raising their voices for the sake of their citizens.

While there are obvious advantages that come with strategic alliances, the tangible impacts for Pacific nations remain negligible. As the UN’s Asia and the Pacific progress report on sustainable development goals states, not a single goal is on track to be achieved by 2030.

Unless these partnerships are grounded in good faith and genuine sustainable development, the grassroots consequences of geopolitics-as-usual will not change.![]()

Dr Sione Tekiteki, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Auckland University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

On October 29, the Spanish town of Paiporta, Valencia, was swept by more rain in four hours than it had received in the past three years. The resulting torrent gutted the entire community, killing over 200 residents. While Valencians have banded together to survive and rebuild, their solidarity of necessity is accompanied by a simmering fury at the government’s failures. The Real News reports from Valencia, Spain.

Producers: Belal Awad, Leo Erhardt

Videography: Mario Capetillo Torres

Video Editor: Leo Erhardt

David – Paiporta resident:

When the water rose all the way up there, that’s when the cell phone warnings came through. By then, my dog had already drowned here on the ground floor, that’s when the alarms went off, the warnings started coming in: “Peep peep! Watch out, the ravines are overflowing.” What happened here is unacceptable. It’s unacceptable.

Narrator:

On October 29th, 2024, the small Spanish town of Paiporta became a flashpoint in an unprecedented natural disaster. A rare weather event caused by the meeting of warm and cold fronts unleashed huge amounts of rainfall on the Spanish region of Valencia. More rain in 4 hours than the previous 3 years combined. The storm – referred to by the abbreviation DANA – claimed the lives of 220 people, with tens of people still missing. Today, the town’s residents are angry, they accuse the regional and central government of a slow and negligent response. But where the authorities have failed, volunteers have stepped in.

Goyo – Volunteer:

Well, it looks like some heads might roll. Watching the news, you get the impression they didn’t issue a very effective warning for people to take the necessary precautions, knowing that such a massive flood was on its way.

But groups like ours are really essential because, right now, we don’t see any military presence distributing food. It’s only the volunteer organizations and NGOs providing support to those in need.

Volunteer:

– Would you like some slices of melon?

– Yeah, we’ve got a Tupperware.

– Of course.

David – Paiporta resident:

They left us abandoned for the first 24 hours. We were alone for the first 48 hours. We were entering supermarkets, grabbing food trying to survive as if there were no government. It wasn’t until the third or fourth day that we finally started seeing some presence from the army and others. We felt completely alone and forsaken. In a country where we pay taxes, this should not be happening. And then, just last night, they pulled six more bodies out from under the mud along the tracks. Does it make sense that after ten days, they still haven’t sent enough personnel to find all the missing, or at least most of them? It’s unacceptable, completely unacceptable.

Paiporta resident:

But as I’m saying, this could happen to any Spaniard. The flood has impacted Valencia. But all of Spain, our leaders have abandoned us. Tomorrow, this could happen somewhere else in Spain. We’ll help, but bear in mind, our leaders won’t. What do we even need those leaders for? I don’t want them; I’ll govern myself, damn it.

Narrator:

It was here in Paiporta, that the King and Queen of Spain, the Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez and the regional leader of Valencia, Carlos Mazon came to visit after DANA. And it was here where they were all greeted with mud and dirt thrown at them by angry locals. Whilst the King and Queen stayed to talk to locals, Prime Minister Sanchez and regional head Mazon, both made a hasty retreat.

David – Paiporta resident:

It’s a huge outrage, and the anger running through the town is impressive. There are a lot of inconsistencies; the numbers they’re giving about the missing don’t add up. They’re still finding people. There are garages they haven’t even been able to check because the walls have collapsed. So they can’t tell the truth. Three homeless people who lived there are nowhere to be found. They’re not listed as missing. In Picaña, there were three or four homeless people in a park who are also unaccounted for. They could write this off as other causes of death. We’re furious, indignant, and feeling a deep-seated rage that’s indescribable.

Chantings:

Where’s your mud? Where’s your mud?

Murderers! Murderers! Murderers!

You’re defending a murderer!

Narrator:

Over 130,000 protesters took to the streets to not only demand the resignation of regional leader Carlos Mazón, but to demand answers. Answers to questions like, why did Valencian residents only receive warning text messages 14 hours after the regional government had received a series of red weather alerts? For many the text messages came all too late.

Chantings:

Resign! Resign!

Where were you when you were needed? Where? You’re all dogs! You, you, and you are worthless!

Protester:

Mazón was completely absent. Here, the people are saving the people. That’s what’s happening here today in the Town Hall square, in this November 9 protest, demanding Mazón’s resignation.

Protester:

We’ve had to coordinate ourselves. We’re doing everything by ourselves. And now they try to paint us as heroes, we don’t have to take care of this, they have to take care of everything. And next week, now that the people are more or less safe, what has to happen is that instead of asking for forgiveness, they resign! Out of pure shame of what they’ve done.

Paul – Valencia resident:

My view is that the management by the Valencian government bordered on criminal negligence, by not warning people, downplaying the tragedy beforehand, and trying to hide their incompetence. The Spanish central government, too, treats us like a colony, more worried about getting the AVE train to Valencia and making sure tourists can still come to the beach. And companies prioritize their interests over the safety of their workers, both on the day of the disaster and in the days afterward.

Lucia – Valencia resident:

I believe it’s our duty as citizens to present our complaints against the entire political mismanagement of this DANA, which led to the loss of countless lives that could have been saved. And the chaos that followed the DANA has been even worse than the DANA itself.

Chantings:

Long live Valencia!

Volunteer:

Sandwiches! Go forward if you want one.

I’m making it with whatever little we have so they can enjoy a little taste of home. We need all of this to go into storage.

Carlota – Volunteer:

We’re all in this together. Nobody is anyone’s enemy. It would be easy for us to have a little disagreement and say you’re on one side, and I’m on the other. But right now, we all need to be together and find a solution. I have my opinions, but I’ll keep them to myself because, right now, the priority is for us all to be here, helping however we can with the resources we have.

Maria del Pilar – Volunteer & victim:

I’m personally very grateful to the youth, to the people of Valencia who came to the towns to help us, to help us clear everything out and clean our homes. I’m so grateful that, if I could, I’d thank every one of these people personally.

Jesus – Paiporta resident:

So many different people have come here — people from all over, from outside, from Valencia. Even people from abroad. It’s been remarkable. We can be proud of everyone who’s come to lend a hand. The people will save the people.

This post was originally published on The Real News Network.

This content originally appeared on Just Stop Oil and was authored by Just Stop Oil.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Just Stop Oil and was authored by Just Stop Oil.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Shortly after he was elected, Donald Trump announced an economic gambit that was aggressive even by his standards. He vowed that, on the first day of his second term, he would slap 25 percent tariffs on imports from Canada and Mexico, and boost those already placed on Chinese products by another 10 percent.

The move set off a frenzy of pushback. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau even flew to the president-elect’s Florida resort to make his case. Economists say the potential levies threaten to upend global trade — including on green technologies, many of which are manufactured in China. The moves would cause price spikes for everything from electric vehicles and heat pumps to solar panels.

“Typically, with tariffs, we’ve seen [companies] pass them along to the consumer,” said Corey Cantor, electric vehicles analyst at Bloomberg NEF. Ansgar Baums, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan foreign policy think-tank Stimson Center, said retaliatory moves from the three targeted countries would only make things worse. “It will drive up consumer costs and hurt those who cannot afford it.”

Trump acknowledges that possibility. But he has argued that tariffs are necessary to force Canada and Mexico to crack down on drugs, particularly fentanyl, and migrants crossing the border into the U.S.

It’s not the first time Trump has turned to tariffs as a foreign policy tool. In 2018 and 2019, he imposed them on a litany of goods, from steel and aluminum to photovoltaic solar panels and washing machines. While the Biden administration eased some of those duties, it kept many in place, especially those targeting China, and recently raised tariffs on Chinese items including electric vehicles, solar cells, and electrical vehicle batteries. Experts say these efforts have done little more than raise prices.

“The consensus on the first round of Trump tariffs is that [they] generally did not improve American productivity,” said Alex Muresianu, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning think tank. The nonprofit calculated that, in the long run, Trump’s first round of tariffs will hurt gross domestic product and cost the United States some 142,000 jobs. Baums was even more blunt about their impact: “They were a big failure. They didn’t achieve much.”

The recently threatened tariffs would ratchet prices even higher on things like solar panels, but are also much more far reaching because of their broad application to North American trading partners. One sweeping impact would be on gasoline prices because, although the U.S. is world’s largest oil producer, older domestic refineries can only process the type of heavier crude that comes from Canada. GasBuddy projects that tariffs could add 35 to 75 cents to a gallon of gas.

Automakers will also be hard hit, as $97 billion in parts and some four million vehicles come from Canada and, especially, Mexico. That’s where some of the more affordable electric vehicles, such as Ford’s Mustang Mach-E and the Chevrolet Equinox, are manufactured. Wolfe Research said that “given the magnitude, we’d expect most investors to assume Trump ultimately does not follow through with these threats” but that, if they were put in place, tariffs would add $3,000 to the price of the average car, regardless of whether it’s powered by gasoline or a battery.

Cantor, at Bloomberg NEF, says adding even a few thousand dollars to the price can drastically expand or contract the potential market of buyers for a vehicle. For example, about 70 percent of consumers consider a $35,000 car, a number that jumps to about 87 percent when a car is $30,000.

“People adjust their behavior,” he said. That could further harm an EV sector that will also likely be reeling from Trump’s rollback of federal tax-credits for electrified vehicles.

Baums doesn’t believe that more tariffs will meaningfully shift industries to the US and the Trump administration “underestimates” how complicated that process would be. Others say some relocation could occur. Michelle Davis, director and head of global solar for research firm Wood Mackenzie, wrote that the levies “would undoubtedly increase domestic manufacturing activity to meet market needs.” But even then, she adds, that “this would result in a more expensive market for domestic buyers.”

In addition to prices, Muresianu also worries that the type of protectionism that Trump favors could stymie innovation. He points to the U.S. shipbuilding industry as an example: it once supplied most of the world’s ships but, in large part due to policies meant to shield domestic shipyards from competition, American vessels have since become drastically more expensive than those made overseas and now account for less than 1 percent of the global total. Tariffs could impose similar stagnancy on other U.S. industries, Muresianu says.

Baums’ concerns are more existential. Trump, he says, is geo-politicizing issues like climate change in ways that will ultimately make it more difficult to share technology, lower costs, and combat greenhouse gas emissions. He would like countries to instead come together and agree that some industries — including cleantech — are too important to put at the center of a trade war.

“The planet is burning,” said Baums. “If there’s anything we should try to cooperate on, it’s stuff that makes a clean transition happen.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The climate cost of Trump’s tariffs on Dec 12, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

By Apenisa Waqairadovu in Suva

Fiji’s coalition government has come under scrutiny over allegations of human rights violations.

Speaking at the commemoration of International Human Rights Day in Suva on Tuesday, the chair of the Coalition of NGOs, Shamima Ali, claimed that — like the previous FijiFirst administration — the coalition government has demonstrated a “lack of commitment to human rights”.

Addressing more than 400 activists at the event, the Minister for Women, Children, and Social Protection Lynda Tabuya acknowledged the concerns raised by civil society organisations, assuring them that Sitiveni Rabuka’s government was committed to listening and addressing these issues.

Ali criticises Fiji government over human rights Video: FBC News

Shamima Ali claimed that freedom of expression was still being suppressed and the coalition had failed to address this.

“We are also concerned that there continue to be government restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly through the arbitrary application of the Public Order Amendment Act, which should have been changed by now — two years into the new government that we all looked forward to,” she said.

Ali alleged that serious decisions in government were made unfairly, and women in leadership continued to be “undermined”.

“Nepotism and cronyism remain rife with each successive government, with party supporters being given positions with no regard for merit, diversity, and representation,” she said.

“Misogyny against certain women leaders is rampant, with wild sexism and online bullying.”

Responding, Minister Tabuya acknowledged the concerns raised and called for dialogue to bring about the change needed.

“I can sit here and be told everything that we are doing wrong in government,” Tabuya said.

“I can take it, but I cannot assure that others in government will take it the same way as well. So I encourage you, with the kind of partnerships, to begin with dialogue and to build together because government cannot do it alone.”

The minister stressed that to address the many human rights violation concerns that had been raised, the government needed support from civil society organisations, traditional leaders, faith-based leaders, and a cross-sector approach to face these issues.

Republished from FBC News with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

By Anita Roberts in Port Vila

Vanuatu has reaffirmed its global leadership in climate action as the first country to launch a technical assistance programme under the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage.

This historical achievement has been announced by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS), according to a statement from the Department of Climate Change (DoCC) and the National Advisory Board (NAB) on Climate Change.

“Vanuatu will benefit from US$330,000 from the new Santiago Network to design a loss and damage country programme as a first step towards getting money directly into the hands of people who are suffering climate harm and communities taking action to address the unavoidable and irreversible impacts on agriculture, fisheries, biodiversity infrastructure, water supply, tourism, and other critical livelihood activities. With such a L&D programme,” the statement said.

“Vanuatu aims to be first in line to receive a large grant from the new UN Fund for responding to Loss and Damage holding US$700 million which has yet to be used.

“Loss and damage is a consequence of the worsening climate impacts being felt across Vanuatu’s islands, and driven by increases in Greenhouse Gas (GHG) concentrations which are caused primarily by fossil fuels and industry.

“Vanuatu is not responsible for climate change, and has contributed less than 0.0016 percent of global historical greenhouse gas emissions.

“Vanuatu’s climate vulnerability is one of the highest in the world.

“Despite best efforts by domestic communities, civil society, the private sector and government, Vanuatu’s climate vulnerability stems from insufficient global mitigation efforts, its direct exposure to a range of climate and non-climate risks, as well as inadequate levels of action and support for adaptation provided to Vanuatu as an unfulfilled obligation of rich developed countries under the UN Climate Treaty.”

The Santiago Network was recently set up under the Warsaw International Mechanism for loss and damage (WIM) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) to enable technical assistance to avert, minimise and address loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change at the local, national and regional level.

The technical assistance is intended for developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.

The statement said that because Vanuatu’s negotiators were instrumental in the establishment of the Santiago Network, the DoCC had worked quickly to ensure direct benefits begin to flow to communities who are suffering climate loss and damage now.

“Now that an official call for proposals to support Vanuatu has been published on the Santiago Network website www.santiago-network.org, there is an opportunity for Vanuatu’s local Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), private sector, academic institutions, community associations, churches and even individuals to put in a bid to respond to the request,” the statement said.

“The only requirement for local entities to submit a bid is to become a member of the Santiago Network, with membership open to a huge range of Organisations, Bodies, Networks and Experts (OBNEs).

“Specifically defined, organisations are independent legal entities. Bodies are groups that are not necessarily independent legal entities. Networks ate interconnected groups of organisations or individuals that collaborate, share resources, or coordinate activities to achieve common goals.

“These networks can vary in structure, purpose, and scope but do not necessarily have legally established arrangements such as consortiums. Experts – individuals who are recognised specialists in a specific field.”

According to the statement, to become a member, a potential OBNE has to complete a simple form outlining their expertise, experience and commitment to the principles of the Santiago Network.

“The membership submissions are reviewed on a rolling basis, and once approved, OBNEs can make a formal bid to develop Vanuatu’s Loss and Damage programme for the UN Fund for responding to L&D,” the joint DoCC and NAB statement said.

“Vanuatu’s Ministry of Climate Change prefers that Pacific based OBNEs apply to provide this TA because they have deep cultural understanding and strong community ties, enabling them to design and implement context-specific, culturally appropriate solutions. Additionally, local and regional OBNEs have been shown to invest in strengthening national skills and knowledge, leaving behind lasting capacities that contribute to long-term resilience, and build strong local ownership and sustainability.”

The deadline for OBNEs to submit their bids is 5 January 2025.

There will be an open and transparent selection process taken by the UN to determine the best service provider to help Vanuatu and its people most effectively address growing climate losses and damages.

In addition to Vanuatu’s historic engagement with the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage, Vanuatu will also hold a board seat on the new Fund for Responding to L&D, as well as leading climate loss and damage initiatives at the International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice, advocating for a new Fossil Fuel Non Proliferation Treaty, developing a national Loss and Damage Policy Framework, undertaking community-led Loss and Damage Policy Labs and establishing a national Climate Change Fund to provide loss and damage finance to vulnerable people across the country.

Republished from the Vanuatu Daily Post with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

Florida keeps trying to kill Betsy Riley.

Riley says it as a joke, a way to make light of surviving three weather-related scares over the past three years. The first time was in 2022, a year after Riley and their partner moved to Alachua County in the northern part of the Sunshine State. On the June day that they brought their then-newborn baby home, a record-setting heat wave overwhelmed the air conditioner until it broke. The next summer, extreme heat struck again, leading to the explosion of a lawn mower’s battery close to where the family’s two dogs were sleeping. Then, this past September, Hurricane Helene sent an oak tree smashing through the roof of their home, bringing a ceiling rafter down on Riley’s partner. Though the branches missed their second child — then 4 months old — by about 5 feet, the infant was showered with insulation foam.

“When I talk about it, I have to keep from crying,” they said. “But you know, nothing stops when you’re a hurricane survivor. You still have to go to work.”

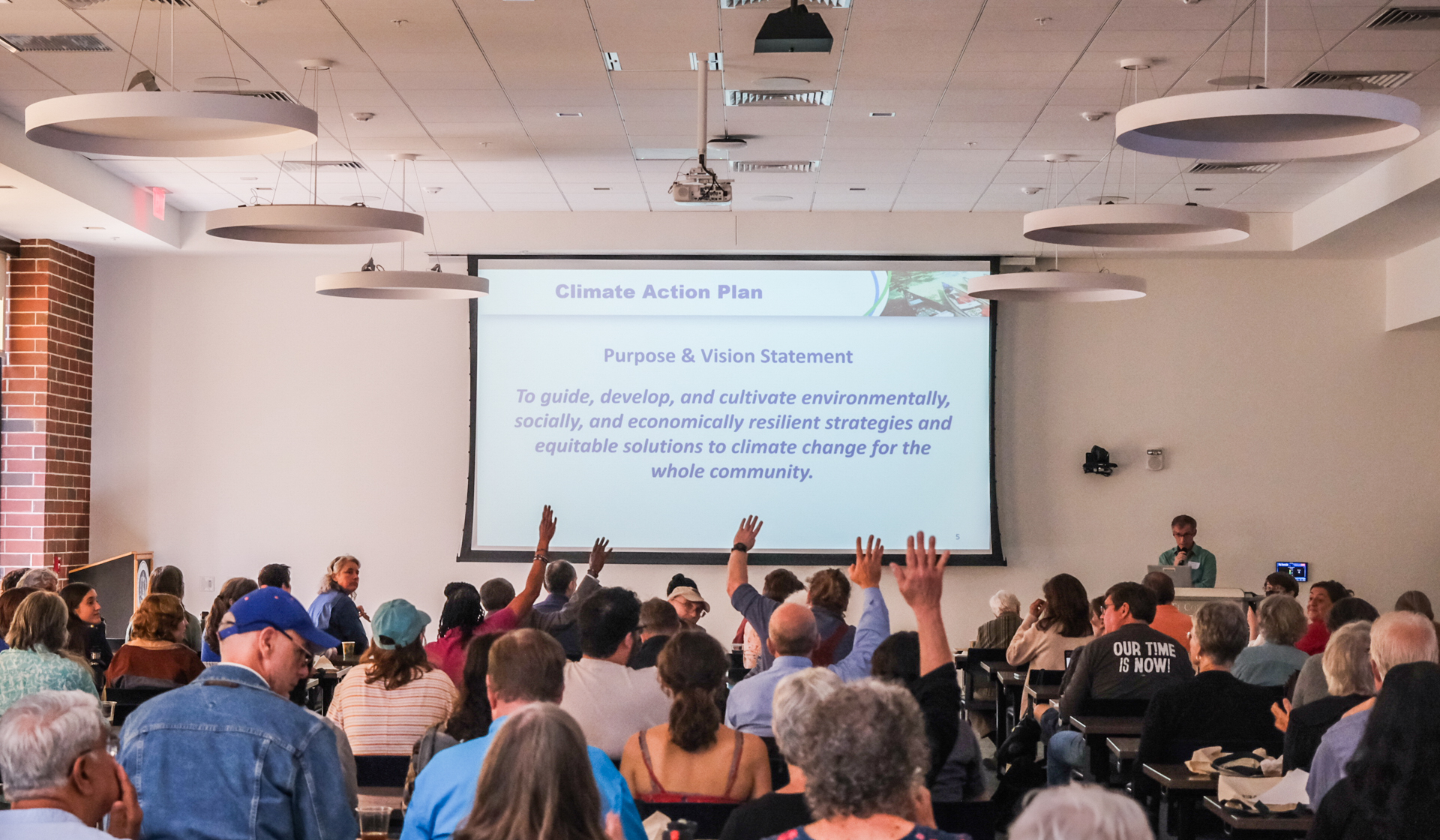

About two months after the hurricane, Riley found themself in like-minded company. As Alachua County’s sustainability manager, the 35-year-old spent a recent Saturday helping lead the inaugural Alachua County Climate Action Summit in Gainesville. Facing a crowd of residents, local leaders, activists, and scientists, one presenter asked, “Who has lived through a hurricane when the power went out?” Hands flew into the air.

The daylong program was intended to tell the community about climate impacts in store for Alachua County, and to get feedback on an official climate action plan, which organizers hope to finalize and begin executing early next year. Within the conference center’s rooms, the atmosphere hummed with urgency, and it was hard to believe that preparing for climate change was at all controversial. For decades, Alachua County has remained a haven for liberals, a blue dot in a deeply red state: Democrats hold most local offices and Democratic candidates for president have garnered landslide majorities since the county backed President Bill Clinton in 1992.

But in Republican-dominated Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis has scrubbed several mentions of “climate change” from the state’s laws, Alachua County’s ambition looks like an easily popped bubble. Even though a large majority of Floridians say they want action on climate change, the state has become increasingly hostile toward many such policies. Recent headwinds, like state laws written to override local ones, precarious federal funding, and a battle over a local utility, threaten to derail the county’s efforts. “To be a Floridian and to be an Alachua County citizen is to hold profoundly different realities,” said Cynthia Barnett, an environmental journalist, in a speech at the summit.

Alachua County sits squarely in North Central Florida, with several hours of interstate buffering residents from coastlines and the nearest big cities, Orlando and Jacksonville. On the day of the summit, downtown Gainesville — the city at the county’s center — bustled with weekend traffic. The city is home to the University of Florida, and some of its 60,000 students were biking to brunch, while others joined throngs of orange-and-blue clad tailgaters in front of the football stadium.

The university is the county’s largest employer, and its progressive influence radiates throughout Gainesville and its 150,000 residents. Leave the city, and the bohemian coffee shops and pride flags vanish, replaced by boiled peanut stands, billboards advertising fireworks, and “Make America Great Again” lawn signs. A little further, and the Spanish moss-draped canopies of live oak trees give way to farmland and pine forests grown for timber. In this perimeter lie the county’s eight other towns, with populations ranging from less than 1,000 to nearly 10,000.