Orientation

One of the main problems with Western media (other than their non-stop anti-Russian propaganda), is the narrow and parochial manner in which they conceive world events. Like realists and liberals of international relations theory, they analyze world events two countries at a time, for example, the U.S. vs Russia. They appear to have little conception of interdependence, like Russia, China, and Iran as a single block. Or the U.S., England, and Israel as another block. No state can make any moves without considering the causes and consequences of their actions for their interdependent states. Secondly, these talking heads fail miserably in understanding that conflicts between states are inseparable from the evolution of global capitalism which, in many respects, is stronger than any state. Thirdly, their “analysis” fails to consider that the world capitalist system has evolved over the last 500 years, as I will soon present. We will see that what is going on in Ukraine is part of a much larger tectonic struggle between Eastern China, Russia, and Iran to create a multipolar world while being desperately opposed by a declining West, headed by the United States and its minions.

A Brief History of Modern Capitalism

According to world systems theory, the global capitalist system has gone through four phases. In each phase, there was a dominant hegemon. First, there was the merchant capital of Italy that lasted from 1450-1640. This was followed by the great Dutch seafaring age from 1610-1740. Next, there was the British industrial system from 1776 to World War I. Lastly, the Yankee system which lasted from 1870 to 1970. Note that over these 500 years the pace of change quickened. In the Italian phase, the city states of Venice and Genoa rose and fell over 220 years. By the time we get to the United States, the time of rise and decline is 100 years. All this has been laid out by Giovanni Arrighi in The Long 20th century. In Adam Smith in Beijing, Arrighi also lays out the reasons he is convinced that China will be the leading hegemon in the next phase of capitalism.

Five Types of Capitalism

Historically there have been five types of capitalism. The first is merchant capital in which profits are made by trade, selling cheap and buying dear. This is what Venice and Genoa did, as did Dutch seafarers on a grander scale. Next, is agricultural capitalism, including the slave system of the United States, Britain, and parts of the Caribbean, South America, and Africa. Then, the British invented the industrial capitalism system in which profit was made by investing the infrastructure of society: railroads, factories, and surplus labor from the wage labor system. Lastly, especially in the 20th century, we have two other forms of capitalism. In addition to being an industrial power after World War II, the United States used its industrial power to invest in the military arms industry and relied on finance capital (stocks and bonds).

Destructive Forms of Capitalism

In the later stage of all four systems, making money from commodities or technologies becomes problematic because it becomes unpredictable what people will buy. For example, after the Depression from 1929-1941, the United States got out of the depression by investing in the military. This was so successful that after World War II, capitalists began investing in the military even during peacetime (Melman, After Capitalism). It provided a much more predictable profit as long as countries continued to go to war. This encourages arming your own country or supplying the whole world, which is what the United States does today. There is also finance capital, where banks invest in stocks, bonds and financial instruments rather than infrastructure (as industrial capitalists did). For the past 50 years military and finance capital are primarily where the ruling class in Yankeedom has made its profits.

In the early phases of capitalism, in all four cycles, commodities were produced which required money as mediation, but the purpose was to produce more commodities and technologies. In the decaying part of the cycle, capitalists would rather invest in finance capital than industrial capital because of the quick turn-around in profits. Investing in building bridges, repairing roads, or building schools will surely benefit capitalists in the long run. Smooth supply chains for capitalist profit and a sound education in high school and college would ensure that workers not only know how to do their jobs but that they would be creative-thinkers and innovators. Capitalists these days don’t want to invest in these things, and this is why the infrastructure in Yankeedom is falling apart and the Yankee population cannot compete with students from other countries with better educational systems.

What is World Systems Theory?

World systems theory is a macro-sociological theory of long-term social change which includes economic theory and world history. It is provocative in at least three ways. One, its basic unit of analysis is the entire world-system of capitalism rather than nation-states. Second, it argues that the so-called socialist societies were not really socialist, but rather state-capitalist. Third, global capitalism organizes itself into a transnational division of labor which ignores the boundaries of nation-states. World-systems theory has been used by historians, international relations theorists, and international political economists to explain the rise and fall of nation-states, the increase and decrease in stratification patterns, as well as rise and decline of imperialism. Christopher Chase-Dunn and Terry Boswell have specialized in understanding social movements and the timing and placing of revolutions from a world-systems perspective.

Economic Zones Within the World-system

Overview of the core, periphery

World-systems are divided into three zones: the core, the semi-peripheral, and the peripheral countries. Economically and politically, core countries dominate other countries without being dominated. Semi-periphery countries are dominated by the core, and, in turn, dominate the periphery. The periphery are dominated by both. Part of the wealth of core countries comes from their exploitation of the peripheral countries’ land and labor through colonization.

Core and periphery

The core countries control most of the wealth in the world capitalist system. Workers are highly specialized, high technology is used. It has an industrial-electronic base. They extract raw materials from the peripheral countries and sell peripheral countries finished products. Core countries have the most highly specialized workers and a relatively small agricultural base, whereas peripheral countries have strong agricultural or horticultural bases and have a semi-skilled urban working class. The peripheral countries have relatively unspecialized labor whose work is labor-intensive with low wages. Much of the work done in peripheral countries is commercial agriculture—the production of coffee, sugar, and cotton.

The core countries are the home of the transnational corporations who control the world. Additionally, the core countries control the major banking institutions that provide international loans, such as the IMF and the World Bank. Finally, the core countries have the most powerful militaries. Paradoxically, when core countries are at their peak, their militaries are not very active. They only become more active as a core country goes into decline, as in the United States. Core countries typically have the most highly trained workers. In their heyday, core countries have strong centralized states that provide for pensions, unemployment, and road construction. In their weak stage, states withdraw these benefits and invest in their military to protect their assets abroad as their own territory falls apart. Core countries have large tax bases and, at their best, support infrastructural development.

The periphery nations own very little of the world’s means of production. In the case of African states or tribes, they have great amounts of natural resources, including diamonds and minerals, but these are extracted by the core countries. Furthermore, core states are usually able to purchase raw materials and cheap labor from non-core states at low prices and yet demand higher prices for their exports to non-core states. Core states have access to cheap skilled professional labor through migration (brain drain) from semi-peripheral states . Peripheral countries don’t have a solid tax base because their states have to contend with rival ethnic and tribal forces who are hardly convinced that taxes are good for them and their sub-national identities.

Peripheral countries often do not have a diversified economic base and are forced by the world market to produce one product. A good example of this is Venezuela and its oil. Peripheral countries have relatively steeper stratification patterns because there are no middle classes for the wealth to spread across. A tiny landed elite at the top sells off most of the land to transnational corporations. The state tends to be both weak and strong. States in the periphery have difficulty forming and sustaining their own national economic policy because foreign corporations want to come and go as they please. On the other hand, if a nationalist or a socialist rise to power, the state will be very strong and dictatorial. This is because they are constantly at war with transnational corporations who seek to overthrow them. Since transnational corporations often do this through oppositional parties, those in power are extremely suspicious of oppositional parties. Hence their label as “authoritarian”. In contemporary world systems, peripheries are found in parts of Latin America and in the most extreme form in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Semi-periphery

The semi-periphery contains countries that as a result of national liberation movements and class struggles have risen out of the periphery and have some characteristics of the core. They can also be composed of formerly core countries that have declined. For example, Spain and Portugal were once core countries in Early Modern Europe. Semi-peripheral countries often take over industries the core no longer wants such as second-generation computers, appliances, or transportation systems. Semi-peripheral states enter the world systems with some degree of autonomy rather than simply a subordinate country. These industries are not strong enough to compete with core countries in “free trade”. Therefore, they tend to apply protectionist policies towards their industry. They tend to export more to peripheral states and import more from core states in trade. In the 21st century, states like Brazil, Argentina, Russia, India, Israel, China, South Korea and South Africa (BRICS) are usually considered semi peripheral.

As I said above, the world capitalist system has changed four times in the last 500 years and each time not only have the configurations of the core countries changed but so have the semi peripheral countries in the world systems. For at least half of capitalist world systems, there were some countries that were outside the periphery, including the United States. Semi-peripheral countries are not fully industrialized countries, but they have scientists and engineers which can lead to some wealth.

Which countries are in the core periphery and semi periphery countries today?

The core countries in the world today are the United States, Germany, Japan, and the Scandinavian social democratic countries of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. Minor core countries are England, France, Italy, and Spain. Eastern European countries are in the semi-periphery. South of the border, there are four semi-periphery countries: Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. More powerful up and coming semi-peripheral states include Saudi Arabia, Israel, Russia, China, and India. Most of Africa is in the periphery of the world systems with the exception of South Africa (semi-periphery).

Where did world systems theory come from?

Immanuel Wallerstein was a sociologist who specialized in African studies, so he had first-hand knowledge of the reality of exploitation by colonists. He was influenced by the work of Ferdinand Braudel who wrote a great three-volume history of capitalism. Wallerstein was also influenced by Marx and Engels, but he thought their history of capitalism was too Eurocentric. He emphasized that the core countries did not just exploit their own workers, but they have made great profits through the systematic exploitation of the peripheral countries for hundreds of years.

Modernization theory

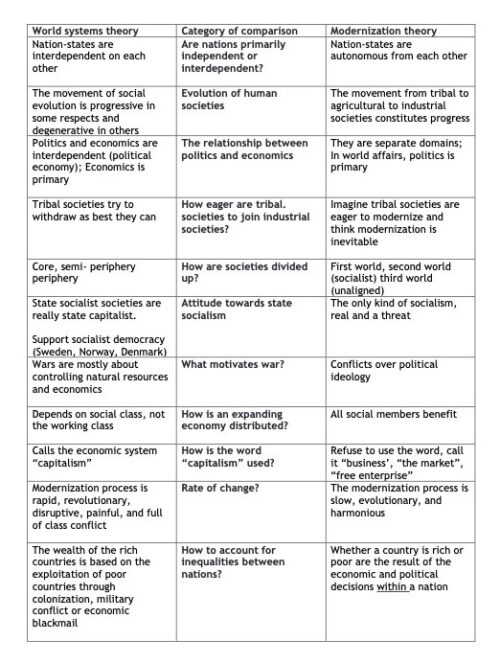

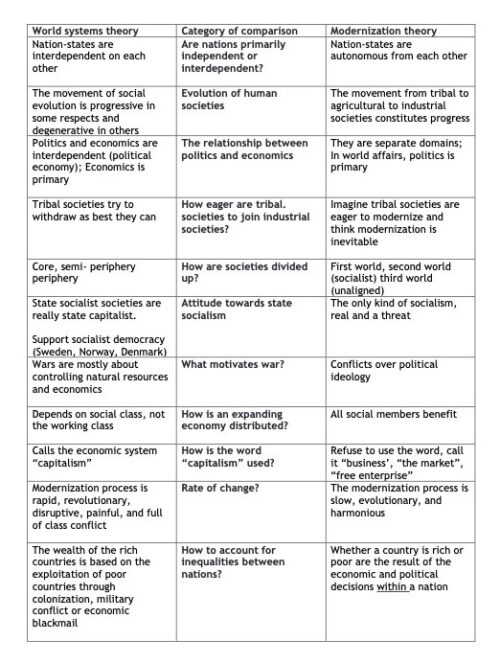

World systems theory was in part a reaction against the anti-communist, modernization theory of international politics that prevailed after World War II into the 1960’s. Please see the table below which compares world systems theory to modernization theory.

Dependency theory of Andre Gunder Frank

Dependency theory of Andre Gunder Frank

Around the same time as world systems theory developed, Andre Gunder Frank developed what came to be called “dependency theory”. This theory also challenged modernization theory’s assumption that countries that were called “traditional societies” were improved by contact with the core countries. He claimed that they were systematically exploited by the core countries, made worse than they were before they had any contact with them. As long ago as 1998, Gunder Frank predicted the rise of China. See his book ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age.

Karl Polyani

Other influences on the world-systems theory come from a scholar of comparative economic systems, Karl Polyani. His major contribution is to show that there was no capitalism in tribal or agricultural civilizations and that the “self-subsisting” economy of capitalism was a relatively recent development. Wallerstein reframed this in world systems terms, with the tribal as “mini-systems”, agricultural civilization as “empires” and the capitalist system as “world economies”. Nikolai Kondratiev introduced patterns he saw in the capitalist world economy that centered around cycles of crisis and wars within very specific time periods.

Interstate System

As I said earlier, in international relations theory, realist and neo-conservative theory and neoliberal theories of the state treat each state as if they were separate units. Applied to today, that would formulate world conflict as a battle between, say, the United States and Russia. Neo-conservative and neoliberal theory treat any alliance between states as secondary epiphenomenon that can be dissolved without too much trouble. Secondly, both these theories operate as if interstate politics are relatively autonomous from economics. To the extent to which these theories mention capitalism, it is the domestic economy of nation-states. Each tries to hide the international nature of capitalism and the extent to which transnational corporations can, and do, override national interests. The ideology of the interstate system is sovereign equality, but this is practically overridden as states are treated as neither sovereign nor equal, especially in Africa.

World systems theory sees states differently. For one thing, nation-states are not like Hobbes atoms which crash against each other in a war of all against all. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, fresh after the Thirty Years’ War, was an attempt to move beyond dynastic empires to nation-states. In core capitalist countries there were never single nation states. The Treaty created a system of nation-states which had rules of engagement, treaties, do’s and don’ts.

Today, between the core, periphery, and semi-periphery countries lies a system of interconnected state relationships. This interstate system arose either as a concomitant process or as a consequence of the development of the capitalist world-system over the course of the “long” 16th century as states began to recognize each other’s sovereignty.

Between these economic zones there were no enforceable rules about how nation-states should act, outside of not impeding the flow of capital between zones. Political domestic elites, international elites, and corporations competed and cooperated with each other, the results of which no one intended. Unsuccessful attempts have been made by the League of Nations and later the United Nations to create an international state. However, nation-states have been unwilling to give up their weapons. Therefore, the international anarchy of capitalist production is still unchecked. The function of the state is to regulate the flow of capital, labor, and commodities across borders and to enforce the structure of market rates. Not only do strong states impose their will on weak states. Strong states also impose limitations on other strong states, as we are seeing with US sanctions against Russia.

Who Will Be the Next World-Economy Hegemon?

Situation in Ukraine

Everything about Ukraine needs to be understood as the desperate clawing of a Yankee empire terrified of being left behind. The U.S. has so far convinced Europe to stay away from Russia and China, but it has nothing to offer. As Gary Olsen said, the Europeans may slowly make deals with Russia and China because they have some sense of where the future lies. So, Western hydra-headed totalitarian media all speak with the same voice: RUSSIA, RUSSIA, EVIL RUSSIA. EVIL PUTIN. Putin certainly had nerve wanting a national economy with its own economic policy. God forbid! But the time is up for Yankeedom and no terrorist police, no military drones, no Republicrats, and no stock exchange jingling with the trappings of divine honor can stop it.

The weakness of Europe

So, if Yankeedom is in decline (and even Brzezinski admitted this) who are the new contenders? Up until maybe five years ago, I thought Germany might be, with its industrial base and its strong working class. But in the last five years German standards of living have declined. It seems that the EU is in the midst of cracking up. There is no leadership with the departure of Angela Merkel. Macron is on the way out in France. All the other countries in Europe, including Italy, are under water with debt. England is the puppy dog of the United States and hasn’t been a global power in over 100 years. Germany, Spain, Italy, and Greece could be helped enormously by allaying themselves with Russia and China, but at this point most Europeans have been bullied and complicit in myopically siding with a collapsing United States. There is a good chance the US will drag most of Europe down with them.

Collapse of the core zones?

As we have seen, according to world systems theory, the history of capitalism has had three zones: core, periphery, and semi-periphery. The countries that have inhabited the three zones have changed along with the dominant hegemon over the last 500 years, and we are now in unprecedented territory. There is a good chance that the entire batch of formerly core states, the United States, Britain, France, and the west will collapse and that the core capitalist system will be without a hegemon (with the possible exception of the Scandinavian countries). China seems to be about ten years away from assuming that position.

2022-2030 the reign of the semi-periphery?

So, is it fair to say there is a huge tectonic shift where most of the core countries will collapse and the world system will have no core for maybe 20 years? It seems clear that the new hegemon is going to be China. Arrighi and Gunder Frank both thought this. But China is still a semi-periphery country and it might take 10-15 years to enter the core. Meanwhile its allies, Russia and Iran, are also semi-periphery countries. In South America, Argentina had the foresight to sign on the Chinese Belt Road Initiative. Brazil and Chile are still uncommitted to China and occupy a semi-peripheral status. The big country in Asia is India. It is very important to the Yankees not to lose control of India, and they have all the reason in the world to beat war drums in an attempt to demonize China. If a right winger such as Modi can refuse to side against Russia in the current events in Ukraine, will a more moderate or social democratic president of India have the vision to see the future lies in aligning with China? I wouldn’t count on it given the behavior of green-social democrat leadership in Germany.

The only European countries who seem to have made their way through 40 years of Neoliberal austerity, the collapse of Yugoslavia, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the rise of fascist parties in Europe are the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. There is no reason why they could not maintain core status, though China would be the leading power.

The new hegemon China and the world-system in 2030

I can imagine the world-system in 2030 could consist of China and the Scandinavian countries in the core, with Russia, Iran, and maybe Brazil, Argentina and Chile on the semi-periphery along with possibly India. I don’t know where to place the US and Europe. Since they are drunk with finance capital, it is unfair to put them in the semi-periphery, which is usually involved in productive scientific endeavors. Yet they are more productive than the peripheral countries. Africa could be the last battleground between the decadent Yankee and European imperialists who live on as neo-colonial crypto-imperialists attempting to either sell arms to Africans or directly set up regimes and enslave Africans to work the mines.

If China is able to develop African productive forces with the Belt Road Initiative, it might be an incentive to calm down the ethnic warfare there. It would be a wonderful thing if the African states could finally control the enormous wealth of their country. We cannot expect too much from China. The best they could do would be to invest in cultivating scientists and engineers to build up Africa as a fully industrialized continent. To me, what matters about China is not arguing whether or not it is really socialist, but that it is doing what Marx liked best about capitalism: developing the productive forces.

The prospects for a world state?

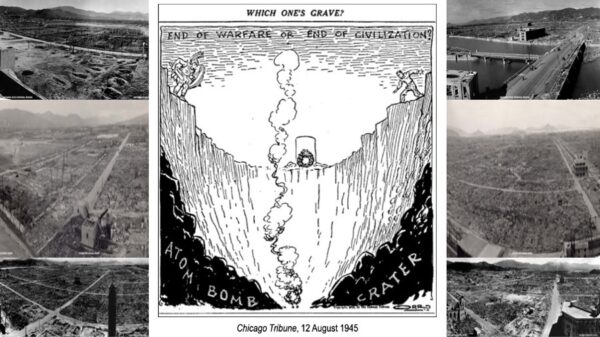

We cannot expect the Yankee state to decline peacefully and not start World War III. Is it possible to have a global capitalist realignment without starting World War III? As Chris Chase-Dunn has advocated for decades, we need a world state that has the capability to enforce a ban on interstate warfare. That is not likely now. The only attempts at this: the League of Nations and the United Nations happened after the misery of two world wars. Both attempts at world state have failed because nation-states would not agree to give up their weapons.

What about world ecology?

But as world systems theorist Chris Chase Dunn points out, a Chinese-centered world still inherits the increasing ecological destruction that has been an inherent part of the world system since the industrial revolution and now the global pandemic. This includes extreme weather (hot and cold), pollution of land and oceans with plastics and the products of industrialization like carbon, flooding from global warming, and desertification of lands due to droughts and monocropping.

What about Marx’s dream of shrinking the ratio between freedom and necessity in the light of ecological disaster?

For Marx and Engels, the dream of socialism was based on abundance. Unfortunately, because socialism first took place in what Wallerstein would call peripheral or semi-peripheral countries, socialism has come to be associated with poverty. An implication that could be drawn under socialism is that people should expect to be poor and share the poverty equally. That is the opposite of how Marx and Engels saw things. They hoped that socialism would first break out in the west in an industrialized country, with an organized working-class party taking the lead. They hoped that the revolution of overthrowing capitalism would preserve its material abundance, technology, and scientific achievements, not tear them to the ground. They wanted to develop the forces of production that capitalism unleashed while abolishing the political economy of private property over means of production. As socialism developed, the collective creativity of workers would shrink the ratio between necessary work and freedom. What does this mean?

This meant that workers would either:

- a) work less and produce the same amount

- b) work the same amount but produce more

- c) work more and produce much more

In other words, workers would have an increase in the number of choices of what to do with their free time because of an increase in the technology and collective creativity to produce more with less. My question is, given the irreversible ecological situation we are in, is it still realistic to expect socialism will continue to be based on abundance? I can imagine that the way China is going, in that part of the world it may still be possible. I also suspect that in the Scandinavian countries it might be possible. The problem is that global pandemics, extreme weather, flooding, desertification, and pollution cannot easily, if at all, be contained within countries that are capitalist or socialist.

How Reliable is World-systems Theory?

I will limit criticisms of world systems theory to those of a political and economic nature. One common criticism is the struggle to do empirical research with a unit of analysis being the entire world system. This is not to say world systems theorists do not do empirical work, because they do. It is more a matter of how to derive meaningful relationships between variables at such a complex level of abstraction. Statistics for individual nation states are easier to manage, although nation-states are not autonomous actors.

Another criticism is that the successes of existing socialist states are in danger of being given the short shrift. Like many in the West, the first line of criticism by world systems theorists of socialist countries is that they are one-party dictatorships. While this may be true, there is good reason why communist parties in power are nervous about the prospect of oppositional parties being used by foreign capitalists to overthrow them. In addition, socialist countries have better records than capitalist countries on the periphery in the fields of literacy (reading and writing), low-cost housing, healthcare, and free education. Please see Michael Parenti, Black Shirts and Reds for more on this.

The third major criticism comes from orthodox Marxist, Robert Brenner. Brenner claims that the emphasis by world systems theorists on the relationship between economic zones comes at a cost to understanding the class structure within and between nation-states. I think world systems theorists are well aware of class relationships, but they choose to focus on the capitalist relationships between states. Lastly, Theda Skocpol argues that world systems theory understates the power of the state in international affairs. The state is not just the creature of transnational capital. States engage in military competition which long s capitalism. State structures compete with each other.

On a positive note, as I said earlier, Christopher Chase-Dunn has done some creative work with Terry Boswell in tracking the timing and location of rebellions and revolutions in the 500 years of the world systems in Spirals of Capitalism and Socialism. In addition, he wrote a very groundbreaking book with Tom Hall Rise and Demise, which challenges Wallerstein by suggesting that there were precapitalist world systems that go all the way back to hunter-gatherers. Also see my book with him, Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present.

• First published in Socialist Planning Beyond Socialism

The post

Tectonic Shifts in the World Economy: A World Systems Perspective first appeared on

Dissident Voice.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

![]()