This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by Radio Free Asia.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Top Vietnamese and foreign officials gathered in Hanoi on Thursday for the funeral of Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong who died last Friday at the age of 80.

Trong, who state media said died of “of old age and serious illness,” served for 13 years as the most powerful leader in the Southeast Asian country’s one-party political system, and spearheaded a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that some critics say has been used to settle factional scores.

President To Lam, who took over Trong’s duties the day before his death was announced, led mourners at the National Funeral Hall in the Vietnamese capital, alongside Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh.

Trong’s coffin was bedecked with his medals and a portrait as his family greeted mourners, who were asked not to bring flowers or envelopes of cash, media reported.

Flags flew at half mast across Vietnam, with somber services also held in Ho Chi Minh City and Trong’s home village of Lai Da in Hanoi’s Dong Anh district.

RELATED STORIES

Facebookers fined, warned about posting information about Nguyen Phu Trong

Nguyen Phu Trong left Vietnam’s Communist Party ripe for strongman rule

The state funeral will last for two days, ending with Trong’s burial at the Mai Dich cemetery, where he will be laid to rest alongside many of the country’s old leaders, on Friday afternoon.

Cambodia’s Senate president and former prime minister Hun Sen and South Korean Prime Minister Han Duk-soo were among the foreign officials attending but many countries sent lower-ranking representatives rather than their top leaders.

“The general secretary had strengthened the enduring brotherly friendship with Cambodia and persistently strived over the years to enhance close cooperation not only between the Cambodian People’s Party and the Communist Party of Vietnam but also between our two governments and peoples,” Hun Sen said in a statement.

Trong was the main architect of Vietnam’s “blazing furnace” anti-corruption drive. The campaign has netted scores of suspects including several senior Communist Party officials and business leaders.

But it has also raised concern about political stability, unnerving some foreign investors, while also fueling complaints that some leaders have used accusations of corruption to settle scores and improve their standing.

“People remember Nguyen Phu Trong through his ‘blazing furnace’ campaigns, but it was this fight against corruption that helped expose the nature of a one-party dictatorship,” said Viet Tan, a pro-democracy group with members inside Vietnam and abroad, which says it aims to aid a transition to democracy.

“Too many communist officials sought to exploit public resources and plunder the people’s property. Not surprisingly, the burning furnace campaigns failed. After many years of rule, the Communist Party of Vietnam has made corruption endemic.”

Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Updated July 19, 2024, 11:28 a.m. ET

Vietnam’s Communist Party chief Nguyen Phu Trong died on Friday at the age of 80, domestic media reported, after serving for 13 years as the most powerful leader in the Southeast Asian country’s one-party political system.

Party Secretary General Trong, who spearheaded a sweeping anti-corruption campaign known as the “Blazing Furnace,” had been sick for some time and had stepped back from his official duties.

“Party Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong has passed away following a period of illness, despite the care and treatment by the Party, the state, doctors and leading health experts,” VNExpress reported.

Trong had been at the helm of the party since 2011 but had hardly been seen in public since January when he attended an extraordinary session of the National Assembly.

State media reported on Thursday that newly appointed president, To Lam, 67, had assumed Nguyen’s duties as Communist Party chief.

Lam was named president in May. As acting general secretary, he is now Vietnam’s top leader and will oversee the work of the Party Central Committee, the Politburo and the Secretariat, according to the Vietnam News Agency.

RELATED STORIES

To Lam: The man with the golden steak is now leading Vietnam

Putin visits Vietnam, aiming to renew Cold War ties

To Lam takes office as Vietnam’s president

Vietnam leadership battle heats up after serial sackings narrow the field

Trong was the main architect of the anti-graft drive that has netted senior party officials and business leaders but also raised new concerns about political stability in what is considered Southeast Asia’s manufacturing hub, and is heavily dependent on foreign investment and trade.

Foreign policy ‘pragmatist’

Carlyle Thayer, a Vietnam expert at the University of New South Wales, said Trong would be remembered as a staunch adherent to the Vietnamese tenets of Marxism-Leninism and socialism, and a proponent of party-building and one-party rule by the Communist Party.

“He will also be viewed as a pragmatist in foreign policy but a stern opponent of peaceful evolution and a ‘color revolution,’” Thayer said

“Particularly in his first term, Trong reined in the sprawling complex of state-owned corporations, general corporations and state banks that flourished as a result of high GDP growth rates and aggressively prosecuted corrupt officials and their networks,” he added.

Trong was born in Hanoi in 1944. He earned a bachelor’s degree in literature from Vietnam National University and was a professor and PhD holder in political science, according to the Nhan Dan newspaper.

He worked as an editor at the Communist Review. In 1996, he was named deputy secretary of the Hanoi Party Committee and afterward ascended through the party ranks.

U.S. Ambassador Marc Knapper noted in a statement that Trong became the first Vietnamese leader to visit the United States when he traveled to Washington to meet with then-President Barack Obama in 2015.

Vietnam and the United States upgraded their relationship to “comprehensive strategic partners” during President Joe Biden’s 2023 visit to Hanoi, Biden said in a statement on Friday.

“The people of Vietnam and the United States – and people across the Indo-Pacific region – enjoy greater security and opportunity today because of the friendship between our two countries,” Biden said in the statement. “That is thanks to him.”

Edited by Mike Firn and Matt Reed.

This story has been updated to add details from Trong’s early career and statements from the U.S ambassador and President Biden.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Staff.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

The Communist Party of Vietnam has expelled National Assembly delegate Le Thanh Van, a member of parliament’s Finance and Budget Committee known for speaking out on various issues, the party said.

The party’s Central Inspection Commission announced on Tuesday that Van had “degenerated in political ideology, morality, lifestyle, self-evolution and self-transformation.”

Police detained Van on July 10 in Thai Binh province and investigated him for “taking advantage of position and power to influence others for personal gain.”

The Thai Binh Police Investigation Agency said his detention was part of an expanded investigation into former National Assembly delegate Luu Binh Nhuong, who was detained for alleged “extortion of property and taking advantage of position and power to influence others for personal gain.”

Both Van and Nhuong had spoken out strongly about national issues in Vietnam’s parliament.

A Vietnamese lawyer, who requested anonymity for security reasons, said the Central Inspection Commission was within its rights to express the party’s view on members but it must also give them the opportunity to defend themselves.

“The party believes that he has ‘evolved and transformed’ himself, so where and how has he evolved and transformed himself?” the lawyer said, using an expression to describe what authorities regard as the right course of action for those seen as critical.

“It must be clear and cannot be made in a press release.”

The lawyer added that the information about Le Thanh Van’s arrest was vague and one-sided, making it impossible for the public to know exactly what had really happened.

“With such little information, it is difficult for outsiders to assess Van’s role and responsibility in this case,” he said. “However, in Vietnam, it can be seen that it is extremely easy to attribute or accuse someone of any criminal act.”

RELATED STORIES

To Lam takes over from Nguyen Phu Trong as Vietnam’s top leader

The deepening ‘securitization’ of Vietnamese politics

Vietnam’s National Assembly approves removal of its leader

The expulsion comes in the midst of an anti-corruption drive known as the “Blazing Furnace” launched by Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, in which dozens of officials and business partners of politicians have been caught up.

The high-profile purges have roiled financial markets and foreign investor confidence and critics say the campaign has been used to target factional rivals.

Speaking out

Van is well-known for speaking out against state agencies and organizations.

In May 2020, he asked the chairman of the National Assembly to consider implementing parliament’s supreme supervision over court operations, through the case of death row prisoner Ho Duy Hai. He said that the Supreme Court’s verdict on Hai’s appeal was unconvincing as there were many unclear issues that concerned the public.

In November 2022, Van said National Assembly delegates needed to discuss and debate more, not just read aloud.

In November 2023, Van spoke about the Dai Ninh hydroelectric plant project in Lam Dong province.

A number of government inspectors had been prosecuted for accepting bribes in connection with the project, and he said a government working group had changed its conclusion from saying in 2020 that it was illegal and should be withdrawn, to amending the project and granting an extension to investors. Van called this “completely illegal.”

Van spoke to parliament In June 2023 about officials “not daring to act and being afraid of taking responsibility,” saying civil servants who did nothing were breaking the law because legal behavior includes action and inaction, and not taking action meant not performing the duties and obligations assigned by the state, which must be handled.

Nguyen Tien Trung, a Vietnamese political observer based in Germany, told RFA he did not believe the charges against Van and Nhuong were justified.

“These are two National Assembly representatives who have made many thorny and controversial statements in the National Assembly,” he said.

“Based on the recent situation of suppressing the Vietnamese democracy movement and arresting many people, I see this as part of a general trend, a general tendency of the Ministry of Public Security to suppress all opposing voices, including opposing voices loyal to the Communist Party, such as Communist Party members like Le Thanh Van.”

Translated by RFA Vietnamese. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Vietnamese.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

Top members of the ruling Communist Party of China will gather Monday to discuss ways to lift the world’s second-biggest economy out of its post-COVID slump and reduce dependence on technology from its geopolitical rival, the United States.

The four-day, closed-door meeting, chaired by President Xi Jinping, is expected to unveil tax system revisions and other debt-reduction measures, steps to deal with a massive property crisis, and policies to boost domestic consumption, policy advisers have said.

Previous third plenum sessions of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee – more than 300 full and alternate members – have unveiled policy initiatives for the next five to 10 years. Some have announced significant shifts.

The 1978 plenum launched Deng Xiaoping’s historic economic reform and opening policies, while the 1984 event confirmed the reform direction in the face of resistance. The 1993 gathering pledged a recommitment to market economic reforms after the clampdown following the Tiananmen massacre.

The 12 years of the Xi Jinping era have put the brakes on market reforms as Xi consolidated power in the party, analysts said.

Xi’s third plenum 2013 “laid out a series of economic reforms, most of which have not succeeded, most of which have not been carried through,” said Barry Naughton, the So Kwan Lok Chair of Chinese International Affairs at the University of California San Diego.

“So everyone is very curious and puzzled to see what this new third plenum is going to bring,” he told Radio Free Asia Mandarin.

The previous plenum, 2018, saw Xi further consolidate power with the scrapping of presidential term limits.

Interventionist policies

This plenum, normally held once every five years, was expected last autumn but delayed without explanation until this month.

Yu Jie, a senior research fellow on China at Chatham House, a British think tank, said the plans to be unveiled in coming days “are unlikely to be policies eagerly waited and favored by private enterprises and global investors.”

Instead of stimulus measures to boost growth, expect “further government intervention to channel economic resources into the strategic and innovation sectors and to guarantee minimum social welfare to the poor,” she wrote on the Chatham House website.

RELATED STORIES

Chinese police target dissidents, petitioners ahead of plenum

China’s jobless struggle amid economic slump

China to hold long-delayed plenary meeting to boost embattled economy

The Communist Party will introduce two economic slogans during the plenum: “New quality productive force” describing making the Chinese economy a leader in technological innovation, and “new national system” of stronger centralized control allocating capital and resources to sectors with strategic significance,” Yu wrote.

“The underlying emphasis here is not on the economy but on geopolitics,” she added.

Chinese state media have tried to create an upbeat mood for the secretive gathering Jingxi Hotel in Beijing.

“Entering July, Chinese people’s expectations will be running high,” according to a June 30 commentary in the Global Times newspaper, predicting “a holistic package of new reform plans” that is expected from the meeting.

“After more than 40 years’ reform and opening-up, Chinese policymakers are becoming both astute and experienced in managing a giant economy like China’s,” it said.

Tech war over consumption

Naughton said, however, Chinese firms and people are not very bullish.

“It’s quite clear that the expectations and household understandings of the economy have deteriorated dramatically since 2022. People have a hard time getting jobs. People’s income growth is slower and they feel much less confident about it,” he told RFA.

The International Monetary Fund has said China’s economy is set to grow 5% this year, after a “strong” first quarter, but other economists warned the recovery has been imbalanced in favor manufacturing and exports over consumption.

“Xi Jinping clearly wanted the majority of the state’s resources and the majority of the state’s attention to be focused on this technological war with the United States, to wean China off the dependence on technology that has been dominated by Americans,” Naughton said.

“He doesn’t care about the rate of growth of consumption of the Chinese people,” he added.

Ahead of the conclave, China is ramping up its “stability maintenance” system, which kicks into high gear targeting those the authorities see as potential troublemakers ahead of top-level meetings and politically sensitive dates in the calendar.

Authorities across China are targeting dissidents and petitioners ahead of next week’s key meeting of the ruling Communist Party, placing them under house arrest or escorting them out of town on enforced “vacations,” Radio Free Asia reported this week.

Several high-profile activists including political journalist Gao Yu, rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and political commentator Zha Jianguo have been targeted for security measures ahead of the third plenary session of the party’s Central Committee, a person in Beijing familiar with the situation who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals said.

Reporting by Ting I Tsai. Editing by Paul Eckert.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By RFA Mandarin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

China’s ruling Communist Party on Thursday expelled ex-Defense Minister Li Shangfu and his predecessor over corruption charges, state media said, in the latest move in a purge that has toppled more than a dozen senior military officers and defense industry figures.

Li’s removal from the party came 10 months after he disappeared from public view, and was reported to be under investigation in connection with the procurement of military equipment. He was sacked without a replacement in October, amid a series of sudden firings and disappearances.

“Li seriously violated political and organizational discipline,” the official Xinhua news agency reported.

“He sought improper benefits in personnel arrangements for himself and others, took advantage of his posts to seek benefits for others, and accepted a huge amount of money and valuables in return,” the agency said in a report also carried by state broadcaster CCTV.

“Li’s violations are extremely serious in nature, with a highly detrimental impact and tremendous harm, according to the investigation findings,” the Xinhua report added.

The official agency used almost identical language for the case of Wei Fenghe, Li’s predecessor as defense minister from 2018 to 2023.

“Wei lost his faith and loyalty,” it said.

Wei’s alleged misdeeds “severely contaminated the political environment of the military, bringing enormous damage to the Party’s cause, the development of national defense and the armed forces, as well as the image of senior officials,” the agency added.

The two generals were stripped of their military ranks, and their cases have been handed to the military procuratorate for prosecution, Xinhua said.

The expulsion of Li and Wei came almost a year after Communist Party chief Xi Jinping fired two top generals of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, which controls the country’s nuclear missiles. Xi also heads the powerful Central Military Commission (CMC).

In the dozen years since Xi Jinping came to power, his wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign has targeted party, state and PLA officials. Nine senior officers and at least four defense industry executives have been sacked.

In 2014, Xu Caihou, a former CMC vice chairman, was expelled from the party and the PLA for corruption. A month later, another vice chairman of the Commission, Guo Boxiong, was ousted from the party, and later given a life prison sentence.

“The signal sent to other PLA leaders is very obvious.” said Ye Yaoyuan, a professor of international studies at the University of St. Thomas.

“For Xi Jinping, he hopes to set a more authoritative example before the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Communist Party Central Committee,” he told Radio Free Asia, referring to a key party meeting in mid-July.

“That is, ‘if something happens to the PLA leaders, I am really willing to take action, and my means of handling it are definitely not a simple transfer or other simple ways to end it.’” Ye said.

Thursday’s report, the first official confirmation that graft was the reason for the sudden and secretive removal of Li and Wei, made no mention of another mystery high-level purge: that of former Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang.

Qin has been absent from public view since he met with the foreign ministers of Sri Lanka and Vietnam in Beijing on June 25, 2023. His disappearance came amid widespread and unconfirmed rumors that he was under investigation for having an affair, and possibly a child, with Phoenix TV reporter Fu Xiaotian.

Edited by Paul Eckert.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Jing Wei for RFA Mandarin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This report contains references to suicide that may be disturbing to readers.

Nearly five years after democratic Taiwan legalized same-sex marriage, LGBTQ+ activism is all but extinct across the Taiwan Strait, where the ruling Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping has cracked down on anyone displaying the rainbow flag in public, members of China’s LGBTQ+ community told Radio Free Asia in recent interviews.

On May 17, 2019, Taiwan passed historic legislation confirming a constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry, making the democratic island the first jurisdiction in the Asia region to do so and prompting a wave of weddings amid a congratulatory tweet from democratically elected president Tsai Ing-wen.

But Chinese propaganda officials warned media organizations there not to make a big deal of the story.

While major Chinese cities once had a thriving LGBTQ+ scene, a gay millennial man born in China who gave only the nickname Haohao said he has noticed a sharp decline in support or respect for the rights of sexual minorities in China, compared with just a few years ago.

“It’s become pretty clear in the past few years that they don’t want us to say or do anything,” Haohao said, adding that gay bars and nightspots have been shutting down, while the rainbow Pride flag is basically banned in public.

“Back in the day when a lot of singers, like A-Mei or Jolin Tsai [from Taiwan] would tour China, there would always be groups of fans waving rainbow flags or wearing rainbow accessories,” he said. “But that’s no longer allowed — they’re not even allowed inside the venue .”

In August 2023, Chinese officials removed an LGBTQ+ anthem titled “Rainbow” by Taiwanese pop star A-Mei from her setlist from a concert earlier this month in Beijing, while security guards forced fans turning up for the gig to remove clothing and other paraphernalia bearing the rainbow symbol before going in, according to media reports.

Sherry Zhang, who goes by the stage name A-Mei, wrote the song for all of her lesbian, gay, bisexual, transexual and questioning friends, and it is frequently heard at Pride events in Taiwan. Her fans among the LGBTQ+ community often turn up and wave rainbow flags or wear rainbow clothing in a show of solidarity, confident that the song will make an appearance.

‘Very strict’ atmosphere

A month after that crackdown, authorities in the central Chinese city of Changsha removed the song “Womxnly” – which commemorates a Taiwanese teenager who was found dead in a school toilet after being bullied by classmates for his “feminine” appearance – from the setlist of Taiwanese pop star Jolin Tsai, after it became an anthem for the island’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transexual and questioning community.

“Things are very strict,” Haohao said, adding that police have started harassing openly gay, bi or transgender people in public on the pretext that they are doing something illegal.

“They may not even have broken the law, but they will still be placed under coercive measures,” he said.

Liu Zhaoyang, a Gen Z gay man currently studying outside China, agreed, citing the case of a volunteer at the Beijing Gay and Lesbian Center who was detained by police on their way to attend a queer event at the embassy of a European country in Beijing, and forced to sign a document agreeing to move away from the capital.

A friend of Liu’s who knew the man now fears that he’ll be next, as he is a known associate, Liu said.

Another non-binary friend is now in prison, after their friends tried to break him out of a “corrective school” for transgender children and young people, he said.

“They were discovered by another parent, who called the police to report them for an illegal gathering and ‘fornication’,” Liu said. “He has been in jail for the past couple of years — I think he got a five-year sentence.”

While homosexuality was decriminalized in China in 1997, and removed from official psychiatric diagnostic manuals in 2001, Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has ushered in a far more conservative attitude to sexuality than his predecessors, with organizers of the annual Shanghai Pride parade announcing it would end in 2020.

Activists have said the crackdown stems in part from the government’s fear of civil organizations as a threat to party rule.

In July 2021, the social media platform WeChat deleted dozens of accounts belonging to LGBTQ+ groups at universities, while two lesbian students at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, identified by pseudonyms Huang and Li, were disciplined in May 2022 for leaving some rainbow flags on a table in the campus supermarket with the hashtag #PRIDE. The women later filed an administrative lawsuit to complain about their treatment.

‘Ridiculous’ ruling

A friend of the women who gave only the pseudonym Su Wei said the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court had contacted the women in May 2023 and told them they wouldn’t be accepting their case.

“He said the reason was an interpretation from the Supreme Court, one that … [contains a clause] relating to national security,” Su said. “The other clauses weren’t applicable. It seems ridiculous.”

The Beijing High People’s Court also refused to accept their administrative lawsuit in June, she said.

Huang has been unable to go overseas as previously planned because of the incident, while the women have since been harassed by police for attending a memorial for a transgender friend who took their own life, Su said.

Huang has since chosen to marry a sympathetic male friend in the hope that there will be someone in her corner if she runs into further legal trouble, she said.

“If you are married, for example, your partner can hire a lawyer for you. There will be someone to help you,” Su said, adding that the rainbow flag case had “made everyone realize how bad this environment is, how they’re going backwards.”

Wu Wei-ting, director of the Institute of Gender Research at Taiwan’s Shih Hsin University, said Xi likely views LGBTQ+ issues as being the result of “Western” or “foreign” ideologies.

“The crackdown includes the party-state machinery taking the lead in attacking or discriminating against gender diversity,” Wu told RFA. “So I would say it’s a pretty comprehensive one.”

“The whole gender diversity movement in China is finding it increasingly difficult to survive,” she said.

Making life intolerable

She cited guidelines from the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television in 2021, which banned “sissy” characters from TV shows, while the authorities also banned the online sale of gender reassignment hormones in 2022, making life intolerable for trans people in China.

“Last year, there were actually several cases of transgender people choosing to commit suicide because they couldn’t get hormones,” Wei said.

Haohao believes that part of the backlash against queer and transgender identities has to do with the Xi administration’s obsession with falling birth rates.

“Young people in China aren’t really having kids nowadays,” he said. “The fertility rate has dropped off a cliff, and the population is falling.”

“They are trying everything to try to get people to give birth … that’s why they are suppressing [us],” he said.

Marriage rates in China are continuing to fall in spite of policies from the ruling Chinese Communist Party aimed at encouraging people to have more children amid a shrinking population, suggesting that the next generation of young people in China has other things on its mind.

Liu Zhaoyang said the crackdown seems to be focused on banning any public expression of sexual minority identities.

“They want to ban all assemblies and parades, whether they’re pride parades or some form of protest against the government,” Liu said. “The space we once had is getting slowly smaller, like boiling a frog in water that’s still only warm.”

For Haohao, the legalization of same-sex marriage by democratic Taiwan five years ago is still a distant dream.

“We can only pray that they will turn a blind eye and not interfere with us too much,” he said. “That would make us very happy. We would be at peace.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Asia and was authored by By Stacy Hsu for RFA Mandarin.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This post was originally published on Real Progressives.

This content originally appeared on The Real News Network and was authored by The Real News Network.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

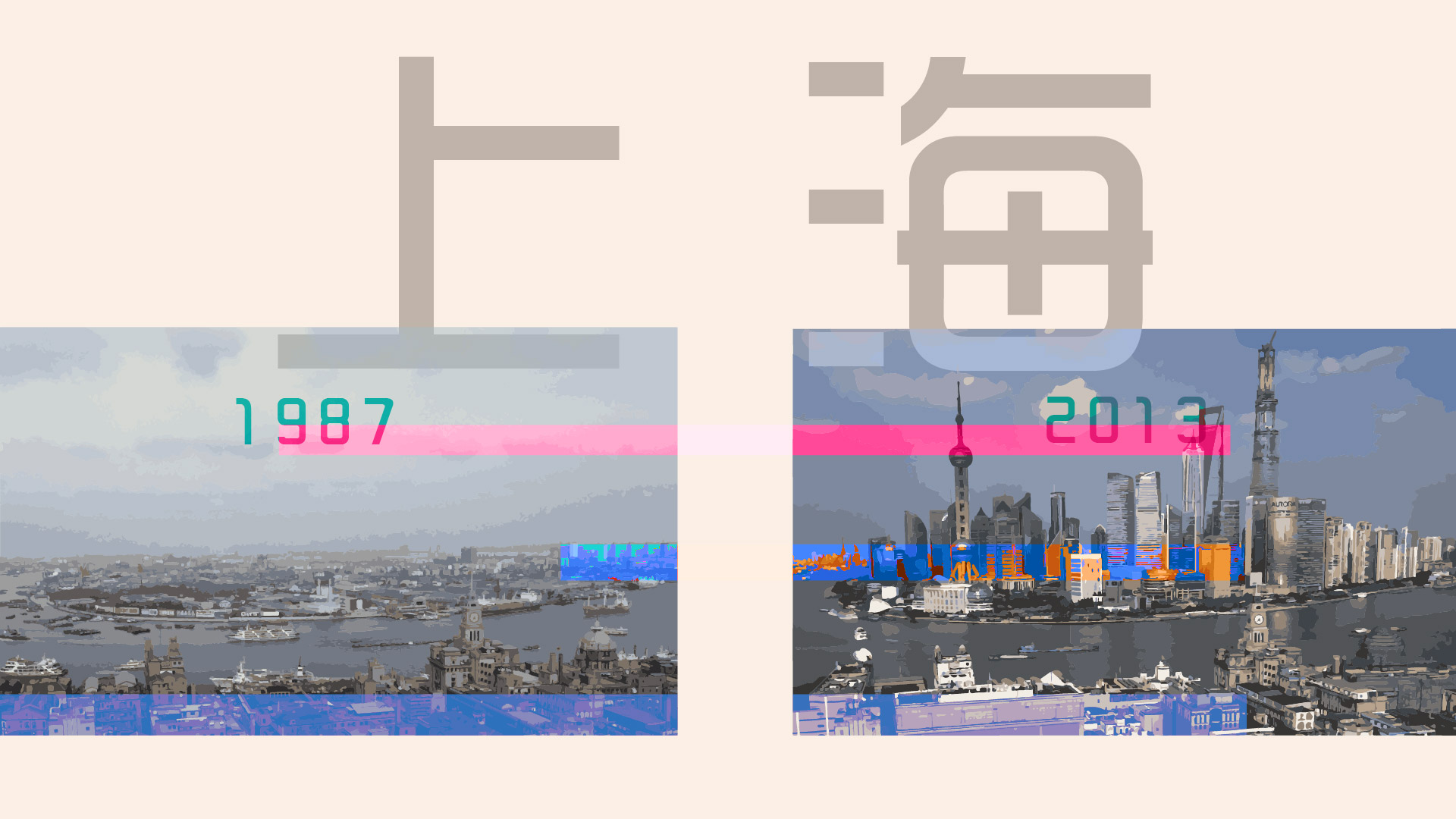

With over 20 million inhabitants each, Shanghai and Beijing are among the “hypercities” of the Global South, including Delhi, São Paulo, Dhaka, Cairo, and Mexico City, far surpassing the “megacities” of the Global North like London, Paris, or New York.1 Walking the streets in China’s cities, you will however, quickly notice one marked difference – the absence of large slums or pervasive homelessness that is so common to most of the rest of the world.

Slums were not uncommon in Chinese cities a few decades ago, from the precarious working class districts of 1930s Shanghai to the shanty towns of British-occupied Hong Kong in the 1950s onwards. How did China manage to develop in a way that decreased mass housing precarity? What are the structural reasons behind it?

This issue of Dongsheng Explains looks into how the Chinese government deals with homelessness, how this issue relates to socialist construction, and how China confronts the challenges posed by rapid economic development, urbanization, and the migration of recent decades.

Why did mass urbanization not create large slums in China?

When reform and opening up began in the late 1970s, 83 percent of China’s population lived in the countryside. By 2021, the proportion of the rural population had fallen to 36 percent. During this period of mass urbanization, over 600 million people migrated from rural areas to cities.

Today, there are 296 million internal “migrant workers” (农民工, nóngmín gōng), comprising over 70 percent of the country’s total workforce.2 Migrant workers became the economic engine of China’s rapid growth, which created the world’s largest middle class of 400 million people.

This historic migration came with many challenges, including the emergence of “urban villages” that had poor living conditions and inadequate infrastructure. Although basic amenities – such as running water, electricity, gas, and communications – were provided, sanitation, public services, fire safety, and other such amenities resembled that of rural villages. Due to lower rents and the lack of other affordable housing, urban villages are largely inhabited by migrant workers.

With the acceleration of urbanization in the 2000s, the Chinese government began to promote large-scale transformation of the old areas of the cities, focusing on renovation of historically deteriorated neighborhoods and the removal of dangerous housing. Between 2008 and 2012, 12.6 million households in urban villages were rebuilt nationwide.Migrant workers are workers whose household registration is still in rural areas and who are engaged in non-agricultural industries or leave their hometowns for work in another part of the country for at least six months of the year.3 At the same time, efforts were made to construct public rental or low-rent housing. For instance, in Shanghai today, families of three or more people with a monthly income of less than 4,200 yuan per person can apply for low-rent housing, with the monthly rent being just a few hundred yuan (or five percent of monthly household income). In 2022, the central government announced the construction of 6.5 million units of low-cost rental housing in 40 cities, representing 26 percent of the total new housing supply in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).4

Indeed the explosion of rural-to-urban migration in recent decades is not a phenomenon unique to China. While understanding that there are different definitions of “slums” used by countries and international organizations, they all point to the same tendency: since the 1970s, slum growth outpaced urbanization rates across the Global South. China’s efforts to upgrade existing precarious housing or build new affordable housing does not, however, explain why China did not develop slums like in so many other countries. Urbanization in China, therefore, must be understood within the context of socialist construction.

What is the “hukou” system and what does it have to do with socialism?

One unique characteristic of China’s urbanization process is that, although policies encouraged migration to cities for industrial and service jobs, rural residents never lost their access to land in the countryside. In the 1950s, the Communist Party of China (CPC) led a nationwide land reform process, abolishing private land ownership and transforming it into collective ownership. During the economic reform period, beginning in 1978, a “Household Responsibility System” (家庭联产承包责任制 jiātíng lián chǎn chéngbāo zérèn zhì) was created, which reallocated rural agricultural land into the hands of individual households. Though agricultural production was deeply impacted, collective land ownership remained and land was never privatized.

Today, China has one of the highest homeownership rates in the world, surpassing 90 percent, and this includes the millions of migrant workers who rent homes in other cities. This means that when encountering economic troubles, such as unemployment, urban migrant workers can return to their hometowns, where they own a home, can engage in agricultural production, and search for work locally. This structural buffer plays a critical role in absorbing the impacts of major economic and social crises. For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, China’s export-oriented economy, especially of manufactured goods, was severely hit, causing about 30 million migrant workers to lose their jobs. Similarly, during the Covid-19 pandemic, when service and manufacturing jobs were seriously impacted, many migrant workers returned to their homes and land in the countryside.

Beyond land reform, a system was created to manage the mass migration of people from the countryside to the cities, to ensure that the movement of people aligned with the national planning needs of such a populous country. Though China has had some form of migration restriction for over 2,000 years, in the late 1950s, the country established a new “household registration system” (户口 or hùkǒu) to regulate rural-to-urban migration. Every Chinese person has an assigned urban or rural hukou status that grants them access to social welfare benefits (subsidized public housing, education, health care, pension, and unemployment insurance, etc.) in their hometown, but which are restricted in the cities they move to for work. While reformation of the hukou system is ongoing, the lack of urban hukou status forces many migrant parents to spend long periods away from their families and they must leave their children in their grandparents’ care in their hometowns, referred to as “left-behind children” (留守儿童 liúshǒu értóng). Though the number has been decreasing over the years, there are still an estimated seven million children in this situation. Today, 65.22 percent of China’s population lives in cities, but only 45.4 percent have urban hukou. Although this system deterred the creation of large urban slums, it also reinforced serious inequities of social welfare between urban and rural areas, and between residents within a city based on their hukou status.

How does the Chinese government deal with homelessness?

In the early 2000s, the issues of residential status, rights of migrant workers, and treatment of urban homeless people became a national matter. In 2003, the State Council – the highest executive organ of state power – issued the “Measures for the Rescue and Management of Itinerant and Homeless in Urban Areas.”5 The new regulation created urban relief stations providing food rations and temporary shelters, abolished the mandatory detention system of people without hukou status or housing, and placed the responsibility on the local authorities for finding housing for homeless people in their hometowns.

Under these measures, cities like Shanghai have set up relief stations for homeless people. When public security – the local police – and urban management officials encounter homeless people, they must assist them in accessing nearby relief stations. All costs are covered by the city’s fiscal budget. For example, the relief management station in Putuo District (with the fourth lowest per capita GDP of Shanghai’s 16 districts and a resident population of 1.24 million), provided shelter and relief to an average of 24.3 homeless people a month from June 2022 to April 2023, which could include repeated cases.6

Relief stations provide homeless people with food and basic accommodations, help those who are seriously ill access healthcare, assist them to return to the locations of their household registration by contacting their relatives or the local government, and arrange free transportation home when needed.

Upon returning home, the local county-level government is responsible to help the homeless people, including contacting relatives for care and finding local employment. For a very small number of people who are elderly, have disabilities, or do not have relatives nor the ability to work, the local township people’s government, or the Party-run street office, will provide national support for them in accordance with the “method of providing for extremely impoverished persons”, which is stipulated in the 2014 “Interim Measures for Social Assistance”. The content of the support includes providing basic living conditions, giving care to impoverished individuals who cannot take care of themselves, providing treatment for diseases, and handling funeral affairs, etc.

This series of relief management measures ensure that administrative law enforcement personnel in the city do not simply expel homeless people from the city, but must guarantee that they receive proper assistance, in terms of housing, work, and support systems.

What are the current challenges of urbanization, migration, and inequality?

While creating relief centers is an important advancement, it is clear that shelters are not a structural solution and they alone cannot meet the needs of a metropolis like Shanghai of 25 million people, let alone the country’s 921 million urban residents. The government has been implementing many structural reforms to address inequality, and to make the cities and the countryside more liveable.

In his report to the 20th National Congress of the CPC, President Xi Jinping said: “We have identified the principal contradiction facing Chinese society as that between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life, and we have made it clear that closing this gap should be the focus of all our initiatives.”7 The unbalanced and inadequate development points to the gap between the countryside and cities, between underdeveloped and industrialized regions, and between the rich and poor.

On a broader scale, the anti-poverty campaigns – highlighted by the eradication of extreme poverty in 2020 – and the rural revitalization strategy have helped alleviate the pressure of migrant workers moving to the cities. The government has invested substantial funds and resources, using diversified ways to alleviate poverty beyond income-transfer schemes, including developing rural industry, education, health care, and infrastructure.8 These measures fundamentally improved the living and employment environment in rural areas and created more opportunities so that people have the option to stay and work in the countryside. For example, every year, more migrants are returning from cities back to their hometowns, which increased from 2.4 million (2015) to 8.5 million people (2019).

Over the last decade, China has implemented reforms to balance the easing of hukou residency requirements and to improve the social welfare of migrant workers, while ensuring that urbanization and population distribution responds to the country’s needs. Since 2010, major cities have gradually relaxed the household registration restrictions for school admission, allowing children of migrant workers to attend public schools like children with local hukou. Furthermore, according to the 2019 Urbanization Plan, cities with populations below three million people are required to remove all hukou restrictions, while bigger cities (under five million) can begin to relax restrictions. The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and the country’s economic strategy until 2035 focus on redistributing income through tax reform, reducing the gap between the rich and poor, and removing the barriers that prevent millions of migrant workers from enjoying the full benefits of urban life. In 2021, the government invested US$5.3 billion to relax the hukou residency rules, and to also boost urban migrants’ spending power as part of the country’s “dual circulation” policy.9

These efforts to tackle the “three mountains” of the high cost of housing, education, and health care faced by all Chinese people, including migrants, is at the center of the government’s vision and policy reforms towards “common prosperity” for all its citizens and the building of a modern socialist society.

ENDNOTES

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Dongsheng News.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.