Caricature of the Third Estate carrying the First Estate (clergy) and the Second Estate (nobility) on its back. “You should hope that this game will be over soon.”

Caricature of the Third Estate carrying the First Estate (clergy) and the Second Estate (nobility) on its back. “You should hope that this game will be over soon.”

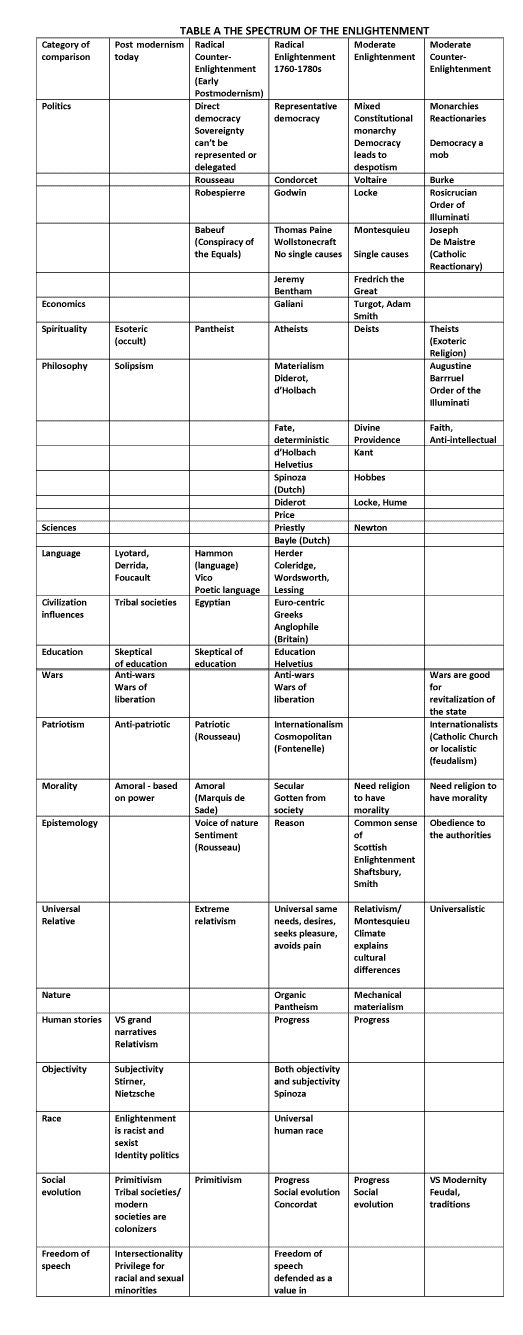

The Counter-Enlightenment is the name given to the oppositional forces that formed during the Enlightenment that fought against the philosophes‘ writings on democracy, republicanism and toleration. These forces were known as the anti-philosophes and sought to maintain the dominance of the monarchy and the church.

The philosophes (French for ‘philosophers’) were eighteenth century intellectuals who “applied reason to the study of many areas of learning, including philosophy, history, science, politics, economics and social issues.” Most importantly, they believed in progress and tolerance and in many different ways sought to highlight injustice and seek ways of changing society for the better.

The anti-philosophes rose up to defend ‘throne and altar’ and over time many of the ideals of the anti-philosophes were taken over by Romanticism in the nineteenth century, and the conservative politics of the twentieth century; for example, in Western culture, “depending on the particular nation, conservatives seek to promote a range of social institutions such as the nuclear family, organized religion, the military, property rights, and monarchy.”

The origins of right-wing politics in Europe are often attributed to Edmund Burke (1729–1797), the Irish philosopher, who is seen as the philosophical father of modern conservatism. His book, Reflections on the Revolution in France, is a criticism of the French Revolution, which itself was partly fueled by the writings of the philosophes, thus setting up the dividing lines between the supporters of radical republicanism and revolution, in opposition to the supporters of the older monarchy and church of the ancien régime.

The idea of the Counter-Enlightenment is itself controversial as some academics argue that an organised force against the Enlightenment was non-existent, or at the very least, a complex debate. For example, Jeremy L. Caradonna (There Was No Counter-Enlightenment) and Robert E. Norton (The Myth of the Counter-Enlightenment) both look at contradictory aspects of the individuals called anti-philosophes. As has been noted the thinkers of the Counter-Enlightenment “did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of society.”

It was Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997), the Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas who popularised the term in his essay ‘The Counter-Enlightenment’. Berlin was critical of the irrationalism of the early conservative figures from the 1700s such as Joseph de Maistre, Giambattista Vico, and J. G. Hamann. He also examined the German reaction to the French Enlightenment and Revolution as the main source of reaction to the Enlightenment in general and which eventually led to the Romanticist movement. Berlin noted that:

Such influential writers such as Voltaire, d’Alembert and Condorcet believed that the development of the arts and sciences was the most powerful human weapon in attaining these ends [e.g. satisfaction of basic physical and biological needs, peace, happiness, justice etc] and the sharpest weapon in the fight against ignorance, superstition, fanaticism, oppression and barbarism, which crippled human effort and frustrated man’s search for truth and self-direction. 1

Writers like Darrin M. McMahon have looked at the early opponents of the Enlightenment in pre-Revolutionary France, while Graeme Garrard has shown in detail the conservative counter-Enlightenment ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a very different perspective on one of the heroes of the French Revolution.

In this essay I will look at the individuals and groups who took a stand against the philosophes through their movements, books, and journals in support of the church and monarchy.

Early opposition to the Enlightenment

Opposition to the philosophes of the Enlightenment did not start with the French Revolution. According to McMahon in his book Enemies of the Enlightenment:

Only recently have scholars begun to acknowledge that conservative salons existed in the eighteenth century in which the philosophes‘ ideas were regarded with horror… 2

Many writers in France mocked the progressive ideas of the philosophes in “a host of satirical plays, libels, and novels published in the late 1750s, 1760s and early 1770s”. 3 McMahon comments that: “It stands to reason that the reaction to the Enlightenment should also have occurred first in the place of its birth and been spearheaded by the very institution – the Catholic Church – charged with maintaining the faith and morals of the realm”. 4

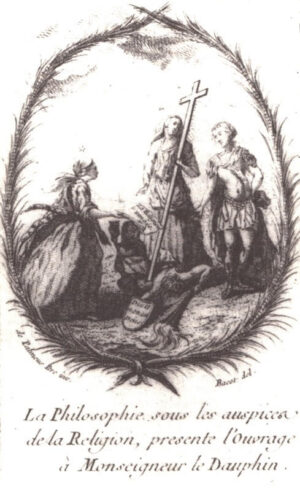

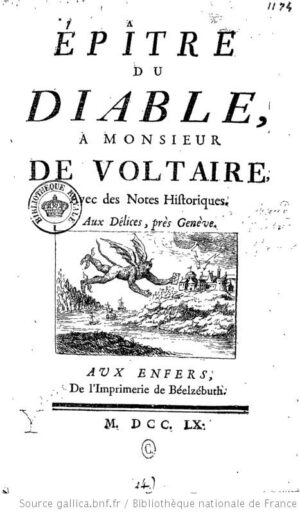

This can be seen, for example, in the Frontispiece to the physician Claude-Marie Giraud’s Epistle from the Devil to M. Voltaire which chronicled Voltaire’s ‘traffic with Satan’, and was republished over thirty times between 1760 and the outbreak of the Revolution.

“Frontispiece to the physician Claude-Marie Giraud’s Epistle from the Devil to M. Voltaire. This brief work, chronicling Voltaire’s traffic with Satan, was republished over thirty times between 1760 and the outbreak of the Revolution.” 5

“Frontispiece to the physician Claude-Marie Giraud’s Epistle from the Devil to M. Voltaire. This brief work, chronicling Voltaire’s traffic with Satan, was republished over thirty times between 1760 and the outbreak of the Revolution.” 5

The adverse reaction to the ideas of the philosophes was evident in the hundreds of books, pamphlets, sermons, essays, and poems written against them, as well as becoming the raison d’être of journals such as the Anée littéraire, the Journal historique et littéraire, and the Journal ecclésiastique. 6 McMahon writes about how the enemies of ‘throne and altar’ and their ‘treasonous’ activities were perceived by the anti-philosophes:

The anti-philosophes saw the philosophes as ‘enemies of the state’, ‘evil citizens’, ‘declared adversaries of throne and altar’, and unpatriotic subjects guilty of human and divine treason. […] Thus, the anti-philosophes frequently accused their opponents of spreading “republican” and “democratic” ideas. The philosophes, they claimed, preached the sovereignty of the people, advocated “perfect equality,” and spoke endlessly of “social contracts.” They lauded the political institutions of the United Kingdom, spreading a contagious “Anglomania” that held up Parliament and the limitations placed on the powers of the English crown as models to be emulated in France. And they talked ad nauseum of “liberty and equality,” natural rights and the “rights of the people” without ever mentioning duties and obligations.” 7

They even appealed to the new dauphin [The distinctive title (originally Dauphin of Viennois) of the eldest son of the king of France, from 1349 until the revolution of 1830] to be wary of the new anti-religious attitude that was being spread by the philosophes: “From this anarchy of the physical and moral universe results, necessarily, the overthrow of thrones, the extinction of sovereigns, and the dissolution of all societies. Oh Kings! Oh Sovereigns! Will you be strong enough to stay on your thrones if this principle ever prevails?” 8

The 1757 frontispiece to the first volume of Jean Soret and Jean-Nicolas-Hubert Hayer’s anti-philosophe journal, La Religion vengée, ou Réfutation des auteurs impies. True philosophy, in possession of the keys to the church, presents a copy of the work to the dauphin, Louis Ferdinand, who looks on approvingly as religion and wisdom trample false philosophy under foot. The latter bears a sign which reads in Latin, “He said that there is no God.” 9

The power of the philosophes‘ ideas could be seen in their influence on the French Revolution of 1789 and in particular on the human civil rights document, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l’Homme et du citoyen de 1789) which was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly during the French Revolution.

Ultra-Royalist reaction

However, the Ultra-Royalist reaction, the nobility of high society who strongly supported Roman Catholicism as the state and only legal religion of France, as well as the Bourbon monarchy, initiated what became known as the Second White Terror, a counter-revolution against the French Revolution.

It provided an opportunity for the counter-Enlightenment conservatives to get their revenge on the revolutionaries, taking the form of militant struggle that resulted in bloody consequences. For example:

The Ultra-Royalist assembly returned after the upheaval of the Hundred Days, this conservative revolution set out to cleanse France of the men and spirits of 1789. Throughout the country, exceptional courts and special jurisdictions tried and punished revolutionary criminals. In the civil service and royal administration as many as fifty thousand to eighty thousand former officials were stripped of their positions, and in the church, the army, and the universities, similar purges were encouraged, although on a smaller scale. In the provinces, particularly in the Midi, marauding gangs took matters into their own hands, hunting down revolutionary collaborators and settling old scores in a great bloodletting known as the White Terror. 10

However, the Terror worried even the king himself as in 1816 Louis XVIII dissolved the chambre introuvable, to the great horror of the Catholic Right: “Louis feared its intransigent refusal to compromise with any vestige of the Revolution, its exaggerated religiosity, and its resolute efforts to exact retribution from the “criminals” who had sullied France.” Thus the conservative pro-monarchy forces had become even more royalist than the king himself. 11

The Chambre introuvable (French for “Unobtainable Chamber”) was the first “Chamber of Deputies elected after the Second Bourbon Restoration in 1815. It was dominated by Ultra-royalists who completely refused to accept the results of the French Revolution.”

The conservative ideas of the Ultras, for example, “the weight of history, the primacy of the social whole, the centrality of the family, the necessity of religion, and the dangers of tolerance” found their way into many right-wing and conservative ideologies of Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.12

Rousseau’s turn against reason and science

Similarly, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s conservative turn laid the groundwork for the future irrationalist Romanticist movement. Despite Rousseau’s popularity as a philosopher of the French Revolution, Rousseau ultimately went against the rationalism and intellectualism of the eighteenth century and moved towards a philosophy based on emotion, imagination and religion.

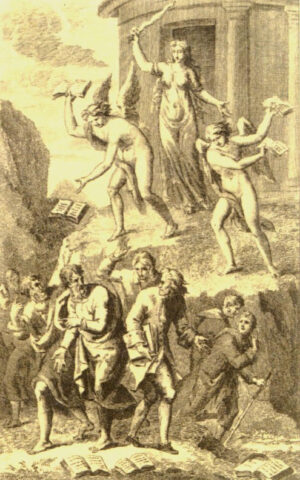

“Flee, vile imposters, no longer sully this temple”, the frontispiece to Pierre-Victor-Jean Berthre de Bourniseaux, Le Charlatanisme dans tous les âges dévoilé (Paris, 1807). Angels of the Lord banish the philosophes from the Temple of Truth. In the foreground, Voltaire, Rousseau, La Mettrie, Plato,and other philosophes flee in despair. 13

“Flee, vile imposters, no longer sully this temple”, the frontispiece to Pierre-Victor-Jean Berthre de Bourniseaux, Le Charlatanisme dans tous les âges dévoilé (Paris, 1807). Angels of the Lord banish the philosophes from the Temple of Truth. In the foreground, Voltaire, Rousseau, La Mettrie, Plato,and other philosophes flee in despair. 13

According to Graham Garrard in Rousseau’s Counter-Enlightenment:

Rousseau’s “unequivocal preference was for the “happy ignorance” of Sparta over Athens, that “fatherland of the Sciences and the Arts” the philosophes so much admired. He regarded virtue as much more important than knowledge or cognitive ability; a good heart is worth inestimable more than the possession of knowledge or a cultivated intellect, he thought” and concludes that “relying on reason – as philosophers do – “far from delivering me from my useless doubts, would only cause those which tormented me to multiply and would resolve none of them. Therefore, I took another guide, and I said to myself, ‘Let us consult the inner light’”. 14

Rousseau’s inward looking attitude and distrust of reason resulted in a very different kind of politics than the philosophes had imagined, as Garrard writes:

Unlike the foundation of political society envisaged by Hobbes and Locke, [Rousseau] stresses the need for a legislator who relies principally on religion and myth rather than reason, self interest, or fear to “bind the citizens to the fatherland and to one another.” […] For Rousseau, religion substitutes for reason as the cement of society and the means of inducing respect for the laws. […] Rousseau’s legislator is a prophet and (perhaps) a poet, whose “magic” produces a nation, rather than a philosopher who appeals to reason. 15

For Rousseau the spread of knowledge was to be controlled and funnelled into localist communities and beliefs, away from modern conceptions of the nation state:

Rousseau was opposed to the popularization of knowledge, not to knowledge per se. In his final reply to critics of his first Discourse, he clarifies position by stressing this distinction between knowledge and its dissemination. “[I]t is good for there to be Philosophers,”he writes, “provided that the People doesn’t get mixed up in being Philosophers”. 16

Leo Strauss’s sentiments exactly! Knowledge as a set of myths that would keep the masses happy but not the kind of universalist knowledge that might lead them to revolt:

The key to Rousseau’s patriotic program is what he referred to as a “truly national education.” Unlike the “party of humanity,” he called for education to be put entirely in the service of particular national communities in order to prevent the corrosive spread of universal ideas and beliefs. He rejected the view put forth by the philosophes that the universal arts and sciences are an adequate basis for political community. 17

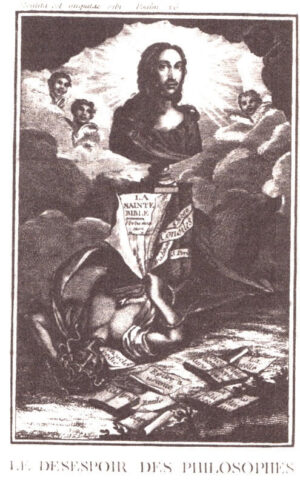

The Despair of the philosophes. Frontispiece to the 1817 edition of the prolific anti-philosophe Élie Harel’s Voltaire: Particularités curieuses de sa vie et de sa mort, new ed. (Paris, 1817). Christ reigns supreme over a fallen medusa, who vomits up the Encyclopédie, Rousseau’s Émile, Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique, and other key Enlightenment texts.” 18

The Despair of the philosophes. Frontispiece to the 1817 edition of the prolific anti-philosophe Élie Harel’s Voltaire: Particularités curieuses de sa vie et de sa mort, new ed. (Paris, 1817). Christ reigns supreme over a fallen medusa, who vomits up the Encyclopédie, Rousseau’s Émile, Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique, and other key Enlightenment texts.” 18

Moreover, Rousseau advocated the use of catharsis and ‘bread and circuses’ to maintain loyalty to the patriotic fatherland (and thereby stymieing any type of burgeoning class consciousness):

Rousseau also advised would-be legislators to establish “exclusive and national” religious ceremonies; games which “[keep] the Citizen frequently assembled;” exercises that increase their national “pride and self esteem;” and spectacles which, by reminding citizens of their glorious past, “stirred their hearts, fired them with a lively spirit of emulation, and strongly attached them to the fatherland with which they were being kept constantly occupied. 19

Rousseau opens one of his most famous books, The Social Contract, with the words ‘Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains’ yet this was a far cry from Marx’s ‘You have nothing to lose but your chains’, as Rousseau refers to rising up against a tyrant, not rising up against one’s own slavery. Especially not the ‘respectable rights’ of ‘masters over their servants’:

The Protestant, republican Rousseau bristled with indignation at the thought of his hardy, virtuous Genevans watching the cynical comedies of Moliere who, “for the sake of multiplying his jokes, shakes the whole order of society; how scandalously he overturns all the most sacred relations on which it is founded; how ridiculous he makes the respectable rights of fathers over their children, of husbands over their wives, of masters over their servants! 20

Rousseau’s move away from enlightened humanism to authoritarianism can be seen in his attitude towards the state whereby any “attempt to liberate a prisoner, even if unjustly arrested, amounts to rebellion, which the state has a right to punish.” 21

If we compare this to Voltaire’s involvement in L’affair Calas we see a very different attitude, as Voltaire fought in defence of a Huguenot merchant who was broken on the wheel for a crime that he had not committed.

Furthermore, Rousseau believed that “The taste for letters, philosophy, and the fine arts softens bodies and souls. Work in the study renders men delicate, weakens their temperament, and the soul retains its vigour with difficulty when the body has lost its vigour. Study uses up the machine, consumes spirits, destroys strength, enervates courage. … Study corrupts his morals, impairs his health, destroys his temperament, and often spoils his reason.” 22

The Enlightenment philosophes thought the opposite: “The less men reason, the more wicked they are,” wrote the Baron d’Holbach. “Savages, princes, nobles and the dregs of the people, are commonly the worst of men, because they reason the least.” 23

The Counter-Enlightenment and Romanticist ideas today

The Enlightenment seems to get blamed for everything these days. In an article titled ‘Enlightenment rationality is not enough: we need a new Romanticism’, the author Jim Kozubek writes:

From the use of GMO seeds and aquaculture to assert control over the food chain to military strategies for gene-engineering bioweapons, power is asserted through patents and financial control over basic aspects of life. The French philosopher Michel Foucault in The Will to Knowledge (1976) referred to such advancements as ‘techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations’.

Foucault does at least remark on a basic aspect of the problem: subjugation and control.

Kozubek comments that “science is exploited into dystopian realities – such fraught areas as neo-eugenics through gene engineering and unequal access to drugs and medical care” but notes that “The biggest tug-of-war is not between science and religious institutional power, but rather between the primal connection to nature and scientific institutional power.”

Historically, the Enlightenment was a battle between the church and the new scientific approaches to knowledge in the 18th century. The philosophes wrote against the power of the church and the monarchies and developed progressive ideas about democracy and republicanism, torture and the death penalty, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.

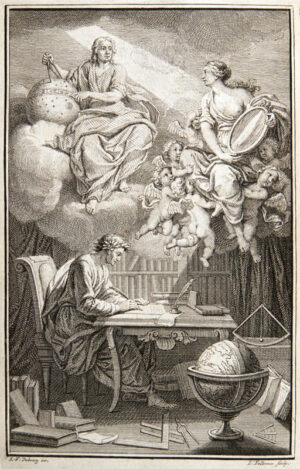

In the frontispiece to Voltaire’s book on Newton’s philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire’s muse, reflecting Newton’s heavenly insights down to Voltaire.

In the frontispiece to Voltaire’s book on Newton’s philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire’s muse, reflecting Newton’s heavenly insights down to Voltaire.

However, this universalising philosophy and writing against injustice of the Enlightenment philosophes is missing from modern analyses of Romanticism, that by the 19th century those battles had developed into the Romanticist ‘primal connection to nature’ versus capitalist technocracy. Yet, what the Romanticists and the technocrats did have in common was that neither questioned slavery: whether it be the slavery of feudalism (which the Romanticists liked to hark back to), or the wage slavery of modern capitalism (which the technocrats prefer to ignore).

In fact, the Romanticists and the technocrats helped each other in a reactionary symbiotic relationship that perpetuated the status quo: the Romanticists had always used technology (to indulge their fantasies, for example, train technology brought them to gaze in awe at the ‘mystical’ Alps), while the technocrats used Romanticism to create diversion and escapism for the masses (thereby avoiding mass uprisings and revolution). This can be seen in the almost wholly Romanticist culture of fantasy, terror, horror, superheroes etc. that dominates global modern culture today in the era of global monopoly capitalism.

The Enlightenment and its opposing counter-Enlightenment, represented the main ideological battles of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, but as people became less and less religious over the ensuing century, Romanticism took over from the irrationalism of the church as the main counter-progressive force in society.

This can be seen also in the ‘suspicion of reason’ contained in the definitions of the post-Romanticist ideologies of Modernism and Postmodernism, and the outright return to Romanticism of Metamodernism. Once the bourgeois revolutions of ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité‘ had been carried through, the universalist ideas of the philosophes were quietly dropped and the anti- (wage) slavery torch passed on to the revolutionary socialists.

It seems that the role of Romanticist movements (including Modernism, Postmodernism, and Metamodernism) is to react to any burgeoning progressive movement, to suck the life blood out of it and while not necessarily killing it, to at least leave it extremely weakened and non-threatening.

Meanwhile, any obvious lack of consistency in Romanticist movements merely points to, and demonstrates, its reactive nature. For example, Romanticist neo-Gothic is full of decoration, yet Romanticist (Modernist) Minimalism, in the form of Bauhaus, for example, is completely devoid of decoration.

McMahons description of the anti-philosophes confirms that reactive view:

If the philosophes assailed religion, then the anti-philosophes must protect it. If the philosophes attacked the king, then his authority must be upheld. If the philosophes vaunted the individual, then the social whole must be defended. If the philosophes corrupted the family, then its importance must be reaffirmed. And if the philosophes advocated change, then the anti-philosophes must prevent it. 24

While the Right may not be able to get away with arguments for the re-establishment of monarchies these days, their ideology is still rooted in organized religion and the social teachings of the church, (combined with the military, and property rights).

The philosophes were progressive thinkers who struggled for radical changes against the injustices of their time. Their universalist writings on liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state are just as important in the world today as they have ever been, especially in an era of increasing globalised poverty where one billion people worldwide live in slums (and yet this figure is projected to grow to 2 billion by 2030) and which is exacerbated by rising inflation and the impacts of war. It is time now for new thinking that is not dominated by the selfish political and war agendas of the billionaire media machine.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.