This is the ninth part in a series about riding night trains across Europe and the Near East to Armenia — to spend some time in worlds beyond the pathological obsessions of President-elect Donald Trump. (This week Trump has been wagging the dog over the annexation of Greenland and busy filling up his cabinet’s clown car with what MAD Magazine would call “the usual gang of idiots.”)

Gara du Nord, the main passenger station in Bucharest. Photo by Matthew Stevenson.

In the late afternoon, when I was back from Bánffy Castle and had inspected a 1990s memorial dedicated to those killed in the anti-Communist movement (many East European cities have one), I retreated to my empty hostel to pass time before dinner.

I had thought of riding out to the Ethnographic Park Romulus Vuia, a collection of old Transylvanian wooden houses (many with thatched roofs that would have thrilled my wife), but by the time I was ready to head there, it had begun to rain and the cobblestones were even more treacherous than before.

Instead, I read my Kindle until I could go to dinner. The best time to visit Cluj-Napoca is in the summer, as the city is full of outdoor restaurants and terraces, but still I found a good place to eat indoors, even though the waitress wasn’t thrilled to see me lugging my folded bicycle to the table. (I try to avoid locking it outside.)

Unlike Western Europe, Eastern Europe—and especially Romania—remains a bargain, and dinner out or a berth on an overnight train can be found for less than $100 (unlike Amtrak, which charges about $600 for many overnight compartments, some of them the size of coffins).

Politically, much of Eastern Europe has never been integrated into the West. Yes, many countries, including Romania, are members of the European Union and NATO, but on the ground they remain a world apart, and the big hole in the donut is former Yugoslavia; few of those republics are EU members, and all are outsiders, as would be Ukraine if admitted into the EU.

+++

The sleeper to Bucharest did not leave until 22:15. A few minutes before departing, the long train pulled into the Cluj-Napoca station. There was no indication on the platform where each numbered car would be stopping.

On the advice of a station officer, I lined up at one end of the platform, only to discover that my sleeping car was at the other end of the arriving train. With only two minutes to get aboard and not wanting to lug the folded bicycle the length of the fourteen-car train, I unfolded it, mounted my bags, and pedaled the length of the train in less than a minute.

I am sure I violated a few rules of Romanian station etiquette, but no sooner had I loaded my bicycle and bags onto the vestibule than the engine whistled and the train rolled into the night.

+++

My first visit to Romania, also on a night train, was in spring 1975, when my father and sister visited me—a student in Vienna—and together we traveled to Budapest and Bucharest. (Actually we went all the way to Constanza, a workers’ paradise of high-rise summer apartments on the Black Sea.)

On the overnight train from Budapest to Bucharest, we made up a bed for my sister (then thirteen) on the floor of the compartment rather than let her sleep alone in her assigned compartment.

That night train left Budapest around 10 p.m., and while waiting for it to back into Keleti station my father taught my sister and me the rudiments of boarding a moving train (we practiced on a few slow-moving locals backing along platforms).

A child of the American Depression, my father had acquired the skill in college, when he got around the United States by “riding the blind,” a perch behind the coal tender of steam engines and in front of the “blind” baggage car at the front of the train.

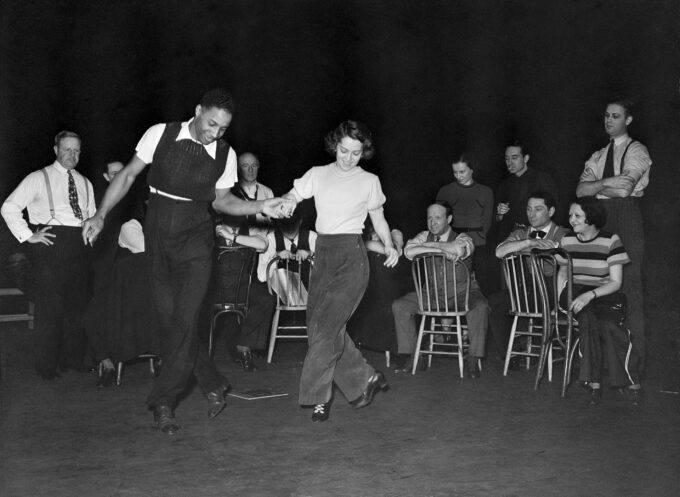

“Riding the blind” (sometimes also called “riding the blinds”) was a step up from hopping freights, which to bindlestiffs and other itinerants in the 1930s were known as “side-door Pullmans”.

After graduating from Columbia in 1940, my father and his close friend Bob Lubar (later managing editor of Fortune and my godfather) rode “the blind” from New York to Los Angeles for $40.

+++

As I had eaten dinner, there was little for me to do on board the night train other than to lock the door and go to sleep. The porter explained that we would arrive in Bucharest around 6:30 a.m., provided the train was on time, and that he would bring breakfast at 6:00 a.m.

On most night trains in Europe—even on some of the newer Austrian trains—breakfast is yogurt, a prepackaged croissant, and lukewarm coffee, which is what I was served at dawn’s early light.

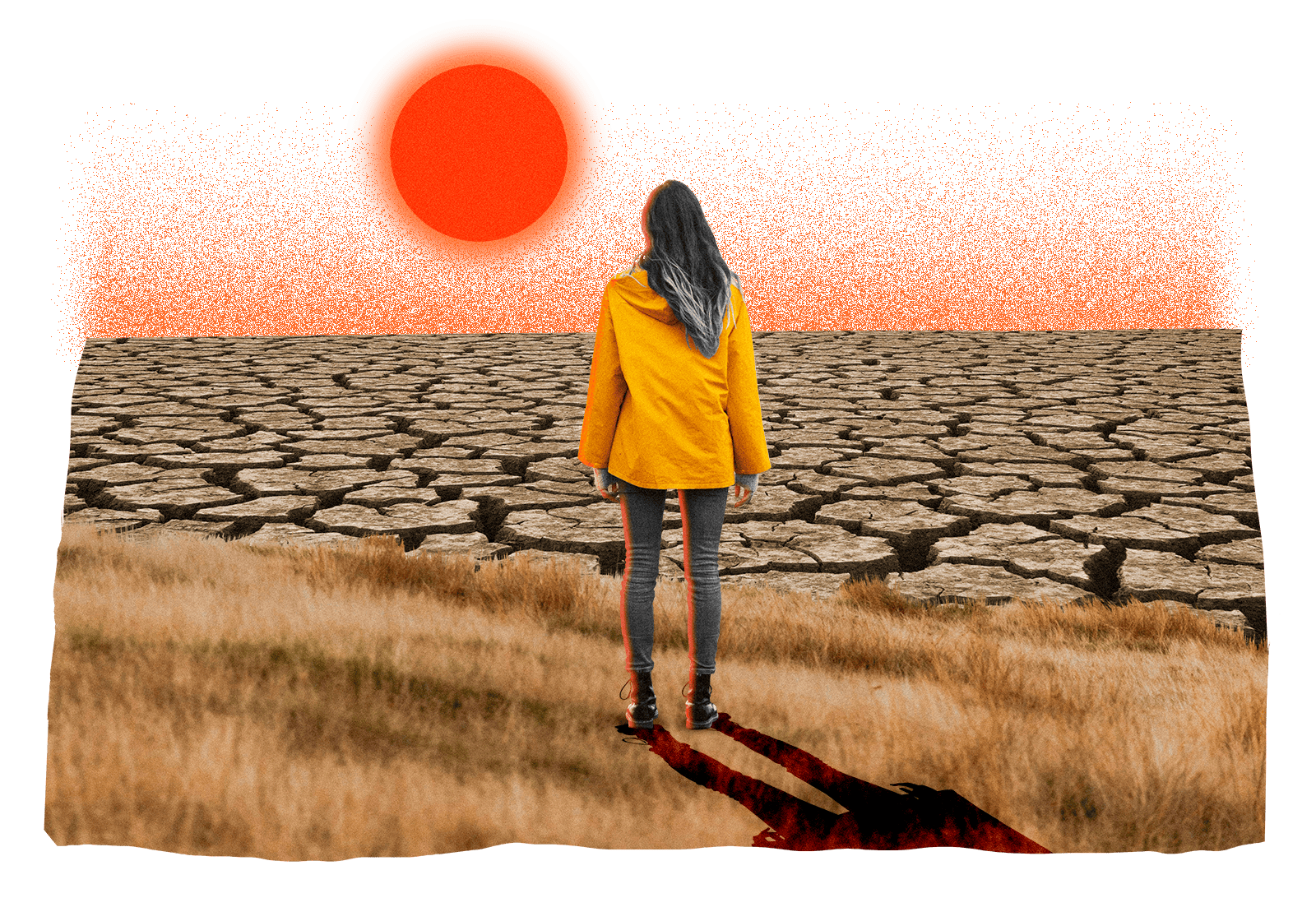

Then, perfectly on time, the train pulled into Bucharest’s Gara du Nord, which both in name and spirit echoes a terminal from Paris in the 1930s.

On only one of my trips to Romania have I come by air. All the others have begun at this station, which has a stately exterior but inside exhibits the jumbled air of a flea-market with trains running out the back.

+++

Rather than spend the night in Bucharest, I had decided to fly later that day directly to Ankara, Turkey.

To be faithful to my plan of taking night trains all the way from Geneva to Armenia, I originally thought of catching a sleeper from Bucharest to Istanbul, and then the high-speed Turkish train to Ankara.

But when I gamed out the connection from Bucharest to Istanbul, I discovered that it would involve three changes at small intermediate stations in Romania and Bulgaria, as the through service—once a mainstay of the historic Orient Express—was no more.

In summer, the train schedule might have been more forgiving with a direct couchette, but in autumn, I was looking at twenty hours on Balkan day coaches and there was no guarantee that I would make all of my connections. So reluctantly I decided to fly.

+++

With the morning free in Bucharest, I assembled the bicycle and went for a city ride. I only had about an hour before I needed to catch a train to the airport, but I decided it would be enough time to make a loop through the downtown.

I began at the Palace of Parliament, by some reckoning one of the largest buildings in the world, conceived as a monument to its spiritual architect, President Nicolae Ceaușescu, whose ego would have been the only thing that might have filled all 365,000 square meters.

The president, however, was tried and executed in 1989, eight years before the building was finished. Twenty-five years later, it remains an endless ballroom in search of dancers.

Nominally, the Romanian parliament meets there, but there are still acres of empty marble rooms sufficient to display 480 chandeliers, not to mention the 1,409 ceiling lights and mirrors that found homes there, thanks to the labors of 700 architects.

Think of Versailles but without all the modesty. Perhaps its best use came in 1992 when the pop singer Michael Jackson put on a concert with the facade as a backdrop. On stage, Michael greeted the audience by shouting: “Hello Budapest, I’m so glad to be here.”

+++

From the Palace of Parliament, I weaved through traffic (it was rush hour on the larger boulevards, but fine to ride on some of the back streets) to the Athénée Palace Hotel, which is located in the city center on Revolution Square.

Down the road were various ministerial offices, which explained why, in the 1989 revolution, protesters tore apart the square and some of the hotel facade as symbols of repression.

I liked riding by the hotel (now part of the InterContinental chain), as that’s where we stayed in March 1975, when I was in Bucharest with my father and younger sister.

While at the hotel, we were joined by a close family friend and my sister’s godmother, whom we called Aunt Marge. She was then in her sixties and had spent a productive life as a social worker, with much of her career spent abroad in places like China and Japan.

She had warmed to the idea of a family trip behind the Iron Curtain to Romania, and had booked herself to London and Bucharest on various airlines. But something went awry when the airport taxi stopped in front of the hotel (then the best in town but still a little shabby).

I was waiting by the front door to greet her, but when the taxi arrived she flew out the rear car door, shouting at the driver and leaving her luggage untouched.

In waiting to get paid, the driver (who spoke no English) had used some gesture, which she interpreted to mean than he would accept payment in a more emotional currency, and she wanted nothing to do with such means of production.

I think part of the problem, lost in transaction, is that in those days the Romanian currency was called the lei.

+++

On this occasion, I ended my bike ride around Bucharest in front of the Museum of the History of the Romanian Jewish Community, which is located in the former United Holy Temple. It was only open between 10:00 and 15:00, but I didn’t need to go inside as I had been there on a recent visit and the display cases (of a vanished Romanian civilization caught in the vice of World War II) were fresh in my mind.

Later, in wanting to know more of this Holocaust story, I downloaded to my Kindle Paul Kenyon’s excellent Children of the Night: The Strange and Epic Story of Modern Romania.

Kenyon is a celebrated broadcast and magazine foreign correspondent who has covered conflicts around the world, and he married into a Romanian family, which is the reason he wrote this history of Romania in the 20th century (the book ends with Ceaușescu and his wife Elena up against the wall of a firing squad in the city of Targoviste).

Of the internal war waged against the Jews Kenyon writes:

It was only in the months and years that followed that the full enormity of Romania’s Holocaust emerged. More Jews were killed by Romania than any other Axis state, aside from Germany itself. According to the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania, the number of Romanian and Ukrainian Jews who perished in territories under Romanian control was between 280,000 and 380,000. Between 120,000 and 180,000 of them died as a result of deportation to Transnistria.

Part of the reason that the fascist leader of Romania, Ion Antonescu, threw in his lot with Hitler’s Nazis is because he hoped that such an alliance might bring back to Romania in a postwar settlement the lost paradise of Transylvania.

+++

Romania joined the Tripartite Alliance with Germany, Italy, and Japan in November 1940 (foreign correspondent Derek Patmore tells the the story of this treachery in his memoir, Balkan Correspondent, which I recommend to anyone who wants to wallow, as I often do, in the politics of betrayal).

Kenyon describes how in the early 20th century nativist anti-Semitism—plus fears of Jews emigrating from Russia and the nearby Pale of Settlement in what is now Ukraine and Moldova—produced toxic nationalism in Romania, no matter whether the leader was a king, a fascist, or a republican.

Of the late 1930s, Kenyon writes: “Jews were barred from marrying Christians and, no matter how long their family had lived in the country, could never acquire the status ‘Romanian by blood’, a term that was written on the official papers of all non-Jews. The policies of hate and discrimination were designed to flatter Hitler into keeping Hungarian hands off Transylvania.”

It all came to naught, however, when Hitler awarded Northern Transylvania (including Cluj) to Hungary in August 1940. After that, Romania could only prove its bona fides to Hitler by being more ruthless against the Jews than even some Germans.

It is not lost in modern European politics that in 1941 Romanian troops spearheaded the Nazi invasions of southern Ukraine, notably Odessa, where atrocities followed them.

The post Romania’s Darkness at Dawn appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.