View of the ceiling paintings in the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci, partially by Paolo Veronese, 1554-1556 (Palazzo Ducale, Venice).

Sometimes one’s best ideas are simple. At the end of the twentieth century, I spent the academic year in residence as a Getty Scholar in Los Angeles, writing about the art museum. I read in the vast literature the memoirs of curators and directors, the histories of various institutions, and also the theory-heavy accounts of academics. And I had the privilege of walking every working day through the Getty Museum, and so I got to know the collection. With so much right at hand to read and see, it’s no wonder that it took me a while to orient myself.

The histories explain that the European art museums were created by moving artistic masterpieces from their original sites, churches, into these public sites. Hence the link of this institution with modernism and the French Revolution, 1789, which turned the king’s palace into a public art museum. (That, at any rate is a useful generalization.) And this movement also led to the birth of art history, which orders and interprets the collections of the public museums. (That is another useful generalization.) When an altarpiece is moved from a church to the gallery, that same object is viewed differently. Viewers no longer come to pray. Now they study the artwork, setting it in art’s history. And so the very same object is understood very differently. What may seem obvious is that so long as the physical object is preserved, so that the same artifact that was in the church is put in the museum, that the artwork has been preserved. However, starting in the late eighteenth-century and continuing more recently a great many ‘museum skeptics’ have denied that conclusion. The object, they allow, is preserved, but the sacred altarpiece is not. In arguing that we cannot understand artworks without taking into account their settings, these theorists thus are skeptical about the survival of art in this move. To put their claim in a phrase: In the museum, the altarpiece has become a work of art, a subject for art historical study.

In my reading, I discovered that there were many museum skeptics. And I was surprised that there was no systematic critical analysis of this position. Some museum skeptics were leftist critics of the art market, while others were conservative critics of secular modernism. The name ‘museum skepticism’, which was my invention, was meant to underline the philosophical implications of this analysis. As epistemological skepticism questions our claims to have knowledge, and moral skepticism the grounds of our morality, so museum skepticism denies that art is preserved in these institutions. Philosophers have a great deal to say about skepticism. And so, when I worked out this analysis, what most surprised me was that no one had developed such a discussion. My Museum Skepticism: A History of the Display of Art in Public Galleries (2006) fully develops an analysis. At that stage, I was only interested in the very general effect of art museum settings. Then I realized that I needed to say more about the various diverse settings of artworks. I needed, first, to consider the unusual setting of the historic center of Naples. (See my In Caravaggio’s Shadow: Naples as a Work of Art (2025). And still more recently, I have discussed Venice as a site for old master art.

Many commentators note that you cannot understand Venetian art, without talking into account its highly distinctive setting. In 1971 in his survey of sixteenth century Italian painting S. J. Freedberg said:

Nature combined with the work of man to enhance the fascination of the sensuous world. The atmosphere of the sea-borne city heightens the existence of seen things. Color is deepened on the damp-saturated air and sharpened by the sea-reflected light, which also may make complicating interactions among colors. The air has an apparent texture which it lends to surfaces perceived through it, and the atmosphere accentuates the sensuous skin of substance.

The situation of painting of this period in land-locked Florence and Rome was very different.

In his more recent account, similarly, developing that idea in more detail, Paul Hills writes:

To the Venetian patrician, the lapping of water at the walls of his palace placed his domicile in touch with the keel’s way, and reminded him of the sea-borne traffic that was carried to and fro over the horizon, moving between the visible and the out-of- sight.

In his account of Venetian painting, John Steer noted, the distinctive features of the art are presented in the very way it depicts its subjects:

The painters of Venice only rarely illustrated their city, and when they did they tended to seize on its permanent characteristics rather than its flux; but its unique visual qualities entered into their whole way of seeing and, fused with the decorative traditions inherited from Byzantium, determined the direction which Venetian painting took.

And Daniel Savoy, focusing on the entry into Venice, has observed:

the builders of medieval and early modern Venice devised a series of water-oriented urbanistic practices to shape the visual and metaphoric image of their city from the open waterway of the lagoon to the narrow canals of the island proper.

Although these scholars offer quite diverse perspectives, they do agree about the need to understand Venice’s site. Entering Florence or Rome is a very different experience. Anyone who visits Venice, even if only briefly, is aware of these essential features of its site.

I was (and am) interested in understanding museum skepticism for two different reasons. I thought it important to consider why the public art museum faces this inherent problem. Too often, critical discussion focuses on just sociological issues or the important political concerns. And I thought that this was an excellent way to link museum studies to more general philosophical concerns. Philosophy, as I understand it, is centrally concerned with skepticism: epistemology with Cartesian skepticism about knowledge; ethics with skepticism about reasoning for right actions; and so on. (I build upon ways of thinking associated with my teacher, the Columbia University philosopher Arthur Danto.) It’s highly worthwhile, I think, to understand what specifically philosophical problems art museums raise. And because the arguments about museum skepticism are structured like those other familiar skeptical questions, we can imagine in advance how debate should proceed.

Museum skepticism is a general analysis the significance of whose claims need still to be understood. Should we be skeptical about the powers of museums to preserve older artworks? The answer to that question is unclear. Descartes thought that his skeptical epistemology made knowledge more secure. But other philosophers disagree. Here, however, I want to turn discussion of the implications of museum skepticism in a different direction Without offering a general conclusion about the plausibility of museum skepticism, let’s consider what this focus on the original site of artworks tells us about the art of Venice. Founded in 826, the Venetian Republic survived (and prospered) until 1797, when it was destroyed by Napoleon. The goal of philosophical aesthetics, as I understand it, should be to understand the relation of Venetian painting to this setting. And so here I offer a very tentative sketch of such an analysis.

When art historians discuss French Impressionism, they are interested in how these painters depict their subject, contemporary urban and rural life. It’s important to observe what is literally left out of the picture. You need to discuss gender, politics and class struggle to understand these paintings. But none of our four writers are centrally interested in the ways that painters depicted the highly distinctive Venetian cityscape. Not until we get to the eighteenth-century masterworks of Canaletto and Guardi do major artists generally focus on that site. (There are some exceptions to this generalization: the narrative cityscapes of Giovanni Bellini and Carpaccio treat the city as a stage setting.) What does concern them, however, is how Venice did influence the ways of visual thinking found in painting produced there. The ever changing reflections created in the lagoons, the dematerialization of sold forms in the canal waters and the ripples produced by the constant boat traffic affect everyday experience. And as Jean-Paul Sartre notes in a marvelously mischievous essay, looking across the city baffles anyone accustomed to mainland reality,

Those princely houses opposite are rising out of the water, are they not? It’s impossible for them to be floating — houses don’t float — or for them to be resting on the lagoon: it would sink under their weight. Or for them to be weightless: you can see they are built of brick, stone and wood, .You cannot but feel them emerging.

Sartre’s “Venice from my window” describes how from an upper floor window, we normally expect to see the buildings in the distance, within obvious walking distance. But in Venice typically such expectations are foiled. To go across the Grand Canal, for example, we need to walk to one of the three bridges, or take a boat across. And when looking at the water in the canals, we see the buildings dematerialized, transfigured into mirrored surfaces, broken by the ripples in the canals. Venice, in short, is an extended exercise in perceptual defamiliarization. Looking around is like experiencing an exotic pictorial space—it is like seeing an artwork as has of course so often been said.

In different, not incompatible ways all of these four scholars indicate how the very special site of the art on the lagoon heavily influences experience. Venetian painting is made in that special visual setting, where it was intended to be displayed. And that means, following our account of museum skepticism, that we need to ask how that specific setting enters into understanding these pictures. But that’s the subject for another, future essay, in which I will take up some accounts of that important concern.

Note:

Museum Skepticism: A History of the Display of Art in Public Galleries. S,J, Freedberg, Painting in Italy, 1500-1600; Paul Hills, Venetian Colour; John Steer, Venetian Painting: A Concise History; and Daniel Savoy, Venice from the Water: Architecture and Myth in an Early Modern City. And Jean-Paul Sartre, Venice and Rome.

The post Museum Skepticism Revisited: the Lessons of Venice appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

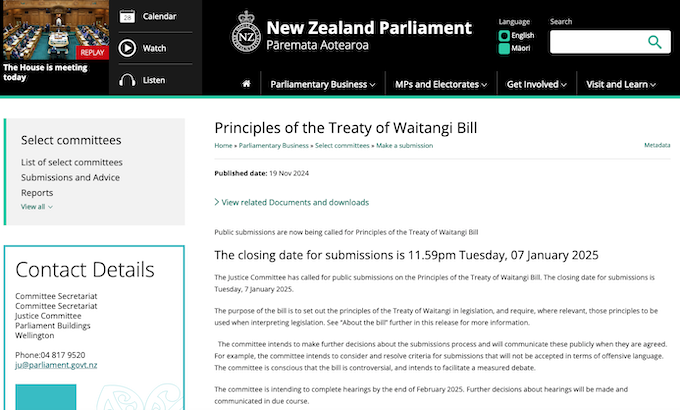

New Zealand MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke performed a haka in a powerful speech during her first appearance in parliament.

New Zealand MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke performed a haka in a powerful speech during her first appearance in parliament.