By Jodesz Gavilan in Manila

Paolo* was just 15 years old when he witnessed the Philippine National Police (PNP) mercilessly kill his father in 2016.

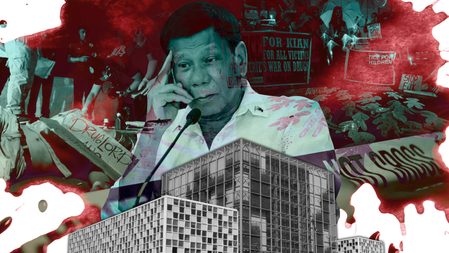

Nearly nine years later, the scales are shifting as Rodrigo Duterte, the man who unleashed death upon his family and thousands of others, now faces the weight of justice before the International Criminal Court (ICC).

“Finally, naaresto din, [pero] dapat isama si [Senator Ronald dela Rosa], dapat silang panagutin sa dami ng pamilyang inulila nila. (Finally, he’s arrested but Dela Rosa should’ve been with him, they should be held accountable for how many families they left in mourning),” he said.

- READ MORE: Special Rappler coverage: The arrest of Rodrigo Duterte

- PHOTOESSAY: Buried in debt only to have their loved ones get a burial — Pacific Journalism Review

- Other Rodrigo Duterte reports

Paolo, then a minor, was also accosted and tortured by Caloocan police — from the same city police who would kill 17-year-old Kian delos Santos less than a year later.

He was threatened not to do anything else or else end up like his father. Paolo carried the threats and the fear over the years, even as he hoped for justice.

This hanging on for hope in the face of devastation was not for nothing.

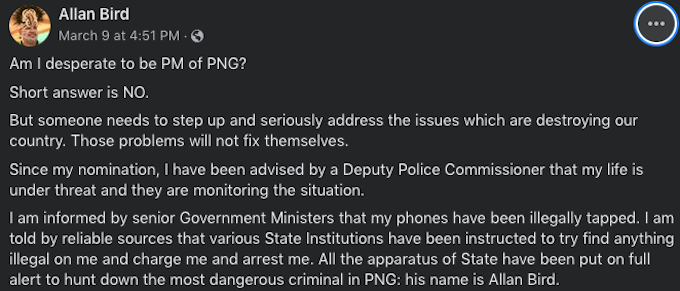

Duterte was arrested today by Philippine authorities following the issue of a warrant by the ICC in relation to crimes against humanity committed during his violent war on drugs.

The ICC has been investigating the killings under Duterte’s flagship campaign, which led to at least 6252 deaths in police operations alone by May 2022. The number reached between 27,000 to 30,000, including those killed vigilante-style.

The Presidential Communications Office said that the government received from the Interpol an official copy of a warrant of arrest.

Duterte was presented by the Philippine government’s Prosecutor-General with the ICC notification of an arrest over crimes against humanity upon his arrival from Hong Kong on this morning.

Slow but sure step to justice

Paolo is not the only one rejoicing over Duterte’s arrest. Many families, including those from drug war hot spot Caloocan City, see this as the long-awaited step toward the justice they have been denied for years.

When the news broke, Ana* was overcome with joy and thanked God for giving families the strength and unwavering faith to keep fighting for justice. She knew the weight of loss all too well.

In 2017, police stormed into their home in Caloocan City and brutally killed her husband and father-in-law in a single night.

Ana, who was five months pregnant at that time, was caught in the violence and was hit by a stray bullet. She and other victims have since been supported by the In Defence of Human Rights and Dignity Movement.

“Sa wakas, unti-unti nang nakakamit ang hustisya para sa lahat ng biktima (At last, justice is slowly being achieved for all the victims),” she recalled thinking when she read that Duterte had been arrested.

But Ana is wishing for more than just imprisonment for Duterte, even as she welcomed the long-awaited accountability from the former president and his allies.

“Sana din ay aminin niya lahat ng kamalian at humingi siya ng kapatawaran sa lahat ng tao na biktima para matahimik din ang mga kaluluwa ng mga namatay (I hope he also admits to all his wrongdoings and asks for forgiveness from every victim, so that the souls of those who were killed may finally find peace),” she said.

Brutality they endured

For the families, the ICC’s move and the government’s action are an acknowledgment of the brutality they endured. The latest development is also a validation of their grief and provides a glimmer of hope that accountability is finally within reach. After years of being silenced and dismissed, they see this moment as the start of a reckoning they feared would never come.

Celina, whose husband was shot dead in a drug war operation, feels overwhelming joy but is wary that the arrest is just part of a long process at the ICC.

“Ang sabi nga po, mahaba-habang laban ito kaya hindi po sa pag-aresto natatapos ito, bagkus ito ay simula pa lamang ng aming mga laban [at] naniniwala kami at aasa sa kakayahan at suporta na ibinibigay sa amin ng ICC [na] sa huli, mananagot ang dapat managot, maparusahan ang may mga sala,” she said.

(As they say, this is a long battle, so it does not end with the arrest. Rather, this is only the beginning of our fight. We believe in and will rely on the ICC’s capability and support, knowing that in the end, those who must be held accountable will face justice, and the guilty will be punished.)

‘Duterte should feel our pain’

The wounds left behind by the drug war killings remain deep. The families’ losses are irreversible, yes, but they see this arrest as a long-awaited step toward the justice they have fought for years to achieve.

It is a stark contrast to the reality they have lived following the deaths of their loved ones. They were constantly under threat from the police who pulled the trigger. Many families had to flee to faraway places, leaving behind their own communities and source of livelihood.

“Nakakaiyak ako, hindi ko alam ang dapat kong maramdaman na sa ilang taon naming ipinaglalaban ay nakamit din namin ang hustisyang aming minimithi (I’m in tears — I don’t know what to feel. After years of fighting, we have finally achieved the justice we have long been yearning for),“ said Betty, whose 44-year-old son and 22-year-old grandson were killed under Duterte’s drug war.

For Jane Lee, the arrest only underscores the glaring disparity between the powerful and the powerless.

“Mabuti pa siya, inaresto ng mga kapulisan. Ang aming mga kaanak, pinatay agad,” she said. “Napakalaki ng pagkakaiba sa pagitan ng makapangyarihan at ordinaryong taong tulad namin.”

(At least he was arrested by the police. Our loved ones were killed on the spot. The difference between the powerful and ordinary people like us is enormous.)

Lee’s husband, Michael, was gunned down by unidentified men in May 2017, leaving her to raise their three children alone. Since then, she has volunteered for Rise Up for Life and for Rights, a group composed mostly of widows and mothers who remain steadfast in demanding justice for drug war victims.

Collective rage

Families from Rise Up in Cebu also voiced their collective rage against Duterte who ordered killings from the presidential pulpit for six years. They hope that Duterte will feel the same pain they felt when their loved ones were forcibly taken away from them.

This afternoon, Duterte condemned the alleged violation of due process following his arrest. His allies are also echoing this messaging, calling the arrest unlawful.

His longtime aide, Senator Bong Go, Go, tried to access Duterte in Villamor Air Base, asking the guards to let him deliver pizza since they hadn’t eaten yet.

“Katiting lang iyan sa ginawa mo sa amin na sinira mo ang aming buhay at hanapbuhay dahil sa iyong pekeng war on drugs,” the families of drug war victims in Cebu said. “Wala kang karapatan na kumuha ng buhay ng iba [kasi] Diyos lang may karapatan kaya sa ginawa mo, maniningil ang taumbayan lalo na kaming mga pamilya ng mga naging biktima.”

(That is nothing compared to what you did to us. You destroyed our lives and livelihood because of your fake war on drugs. You have no right to take another person’s life; only God has that right. Because of what you have done, the people will demand justice, especially we, the families of the victims.)

There is still no clear information on what comes next, whether Duterte will be immediately transferred to the International Criminal Court headquarters in The Hague, Netherlands, or if legal battles will delay the process.

But Mila*, whose 17-year-old nephew was killed by police in Quezon City in 2018, hopes for one thing if the former president finds himself in a detention cell soon: “Sana huwag na siya lumaya (I hope he is never set free).”

Republished from Rappler with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.