COMMENTARY: By Refaat Ibrahim

Palestinians have always been passionate about learning. During the Ottoman era, Palestinian students travelled to Istanbul, Cairo, and Beirut to pursue higher education.

During the British Mandate, in the face of colonial policies aimed at keeping the local population ignorant, Palestinian farmers pooled their resources and established schools of their own in rural areas.

Then came the Nakba, and the occupation and displacement brought new pain that elevated the Palestinian pursuit of education to an entirely different level.

Education became a space where Palestinians could feel their presence, a space that enabled them to claim some of their rights and dream of a better future. Education became hope.

In Gaza, instruction was one of the first social services established in refugee camps. Students would sit on the sand in front of a blackboard to learn.

Communities did everything they could to ensure that all children had access to education, regardless of their level of destitution. The first institution of higher education in Gaza — the Islamic University — held its first lectures in tents; its founders did not wait for a building to be erected.

I remember how, as a child, I would see the alleys of our neighbourhood every morning crowded with children heading to school. All families sent their children to school.

When I reached university age, I saw the same scene: Crowds of students commuting together to their universities and colleges, dreaming of a bright future.

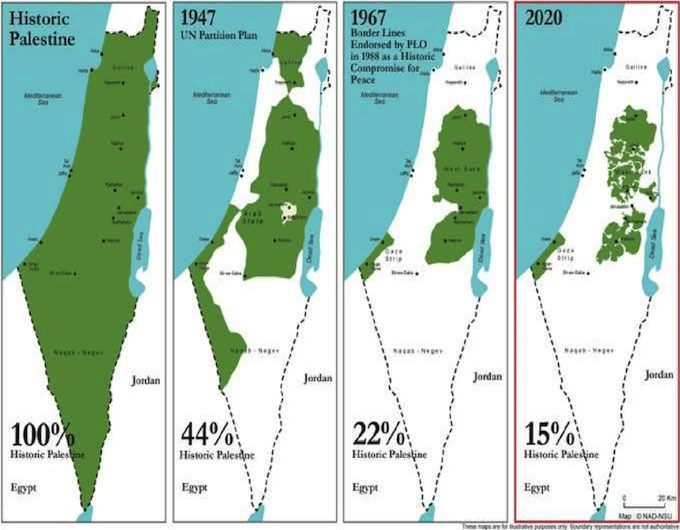

This relentless pursuit of education, for decades, suddenly came to a halt in October 2023. The Israeli army did not just bomb schools and universities and burn books. It destroyed one of the most vital pillars of Palestinian education: Educational justice.

Making education accessible to all

Before the genocide, the education sector in Gaza was thriving. Despite the occupation and blockade, we had one of the highest literacy rates in the world, reaching 97 percent.

The enrolment rate in secondary education was 90 percent, and the enrolment in higher education was 45 percent.

One of the main reasons for this success was that education in Gaza was completely free in the primary and secondary stages. Government and UNRWA-run schools were open to all Palestinian children, ensuring equal opportunities for everyone.

Textbooks were distributed for free, and families received support to buy bags, notebooks, pens, and school uniforms.

There were also many programmes sponsored by the Ministry of Education, UNRWA, and other institutions to support talented students in various fields, regardless of their economic status. Reading competitions, sports events, and technology programmes were organised regularly.

At the university level, significant efforts were made to make higher education accessible. There was one government university which charged symbolic fees, seven private universities with moderate to high fees (depending on the college and major), and five university colleges with moderate fees.

There was also a vocational college affiliated with UNRWA in Gaza that offered fully free education.

The universities provided generous scholarships to outstanding and disadvantaged students.

The Ministry of Education also offered internal and external scholarships in cooperation with several countries and international universities. There was a higher education loan fund to help cover tuition fees.

Simply put, before the genocide in Gaza, education was accessible to all.

The cost of education amid genocide

Since October 2023, the Zionist war machine has systematically targeted schools, universities, and educational infrastructure. According to UN statistics, 496 out of 564 schools — nearly 88 percent — have been damaged or destroyed.

In addition, all universities and colleges in Gaza have been destroyed. More than 645,000 students have been deprived of classrooms, and 90,000 university students have had their education disrupted.

As the genocide continued, the Ministry of Education and universities tried to resume the educational process, with in-person classes for schoolchildren and online courses for university students.

In displacement camps, tent schools were established, where young volunteers taught children for free. University professors used online teaching tools like Google Classroom, Zoom, WhatsApp groups, and Telegram channels.

Despite these efforts, the absence of regular education created a significant gap in the educational process. The incessant bombardment and forced displacement orders issued by the Israeli occupation made attendance challenging.

The lack of resources also meant that tent schools could not provide proper instruction.

As a result, paid educational centres emerged, offering private lessons and individual attention to students. On average, a centre charges between $25 to $30 per subject per month, and with eight subjects, the monthly cost reaches $240 — an amount most families in Gaza cannot afford.

In the higher education sector, cost also became prohibitive. After the first online semester, which was free, universities started requiring students to pay portions of their tuition fees to continue distance learning.

Online education also requires a tablet or a computer, stable internet access, and electricity. Most students who lost their devices due to bombing or displacement cannot buy new ones because of the high prices. Access to stable internet and electricity at private “workspaces” can cost as much as $5 an hour.

All of this has led many students to drop out due to their inability to pay. I, myself, could not complete the last semester of my degree.

The collapse of educational justice

A year and a half of genocide was enough to destroy what took decades to build in Gaza: Educational justice. Previously, social class was not a barrier for students to continue their education, but today, the poor have been left behind.

Very few families can continue educating all their children. Some families are forced to make difficult decisions: Sending older children to work to help fund the education of the younger ones, or giving the opportunity only to the most outstanding child to continue studying, and depriving the others.

Then there are the extremely poor, who cannot send any of their children to school. For them, survival is the priority. During the genocide, this group has come to represent a large portion of society.

The catastrophic economic situation has forced countless school-aged children to work instead of going to school, especially in families that lost their breadwinners. I see this painful reality every time I step out of my tent and walk around.

The streets are full of children selling various goods; many are exploited by war profiteers to sell things like cigarettes for a meagre wage.

Little children are forced to beg, chasing passersby and asking them for anything they can give.

I feel unbearable pain when I see children, who just a year and a half ago were running to their schools, laughing and playing, now stand under the sun or in the cold selling or begging just to earn a few shekels to help their families get an inadequate meal.

About optimism and courage

For Gaza’s students, education was never just about getting an academic certificate or an official paper. It was about optimism and courage, it was a form of resistance against the Israeli occupation, and a chance to lift their families out of poverty and improve their circumstances.

Education was life and hope.

Today, that hope has been killed and buried under the rubble by Israeli bombs.

We now find ourselves in a dangerous situation, where the gap between the well-to-do and the poor is widening, where an entire generation’s ability to learn and think is being diminished, and where Palestinian society is at risk of losing its identity and its capacity to continue its struggle.

What is happening in Gaza is not just a temporary educational crisis, but a deliberate campaign to destroy opportunities for equality and create an unbalanced society deprived of justice.

We have reached a point where the architects of the ongoing genocide are confident in the success of their strategy of “voluntary transfer” — pushing Palestinians to such depths of despair that they choose to leave their land voluntarily.

But the Palestinian people still refuse to let go of their land. They are persevering. Even the children, the most vulnerable, are not giving up.

I often think of the words I overheard from a conversation between two child vendors during the last Eid. One said: “There is no joy in Eid.” The other one responded: “This is the best Eid. It’s enough that we’re in Gaza and we didn’t leave it as Netanyahu wanted.”

Indeed, we are still in Gaza, we did not leave as Israel wants us to, and we will rebuild just as our ancestors and elders have.

Refaat Ibrahim is a Palestinian writer from Gaza. He writes about humanitarian, social, economic and political issues related to Palestine. This article was first published by Al Jazeera and is republished under Creative Commons.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.