The Interior Department has documented the deaths of more than 500 Indigenous children at Indian boarding schools run or supported by the federal government in the United States which operated from 1819 to 1969. The actual death toll is believed to be far higher, and the report located 53 burial sites at former schools. The report was ordered by the first Indigenous cabinet member, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, whose grandparents were forced to attend boarding school at the age of 8. “It’s kind of a misnomer to actually call these educational institutions or schools themselves when you didn’t have very many people graduating, let alone surviving the dire conditions of those schools,” says Nick Estes, historian and co-founder of The Red Nation. Estes says the institutions were part of a “genocidal process” of “dispossession and theft of Indigenous people’s lands and resources.”

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: A new report by the Interior Department has documented the deaths of 500 Indigenous children at Indian boarding schools run or supported by the federal government in the United States, but the actual death toll is believed to be far higher. The report also located 53 burial sites at former schools, which were run for over a century. The report marks the first time the Department of Interior has documented some of the horrific history at the schools, known for their brutal assimilation practices forcing students to change their clothing, language and culture.

The report was ordered by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo. Her grandparents were forced to attend boarding school at the age of 8. She spoke on Wednesday.

INTERIOR SECRETARY DEB HAALAND: For more than a century, tens of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their communities and forced into boarding schools run by the U.S. government, specifically the Department of the Interior, and religious institutions. …

When my maternal grandparents were only 8 years old, they were stolen from their parents’ culture and communities and forced to live in boarding schools until the age of 13. Many children like them never made it back to their homes. …

The federal policies that attempted to wipe out Native identity, language and culture continue to manifest in the pain tribal communities face today, including cycles of violence and abuse, disappearance of Indigenous people, premature deaths, poverty and loss of wealth, mental health disorders and substance abuse. Recognizing the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning. We must also chart a path forward to deal with these legacy issues. …

The fact that I am standing here today as the first Indigenous cabinet secretary is testament to the strength and determination of Native people. I am here because my ancestors persevered. I stand on the shoulders of my grandmother and my mother. And the work we will do with the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative will have a transformational impact on the generations who follow.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. On Thursday, Matthew War Bonnet, who was brought to a boarding school on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota at the age of 6, testified about his experience before the House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples.

MATTHEW WAR BONNET: My boarding school experience is very painful and traumatic. I remember when I first got to school. The priests took us to this big room which had six or eight bathtubs in it. The priest took all us little guys and put us in one tub, and he scrubbed us hard with a big brush. The brush made our skins and our backsides all raw. And we had to have our hair cut. The school then put all the little guys in the same dormitory. We were together, the first through fourth grades. At nighttime you could hear all the children crying.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about the history of Indian boarding schools run or supported by the U.S. government, we’re joined by Nick Estes in Minneapolis, writer, historian, author of the book Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. He’s co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

Nick, welcome back to Democracy Now! Talk about the significance of this new Interior Department report.

NICK ESTES: Thanks so much for having me, Amy.

And as you could hear in the voices of the people, Secretary Haaland, this is a very emotional experience for a lot of Indigenous people in this country. And it should be an emotional experience for non-Indigenous people in this country. This is quite a historic moment in time. Although it’s not new news to Indigenous people, it might be new news to those who are hearing this horrific genocidal process that has taken place.

I think, you know, there’s a reason why the forcibly transferring of children from one group to another group is an international legal definition of genocide. That’s what we’re talking about, because taking children, or the process of Indian child removal, has been one strategy for terrorizing Native families for centuries, from the mass removal of Native children from their communities into boarding schools, as this new report lays out, from their communities into their widespread adoption and fostering out to mostly white families, which happened primarily in the 20th century.

This is a historic report in that regard, because it documents, I think for the first time, the federal government admitting to this genocidal process. Of course they don’t use that language in this report, but many of the researchers, most of whom were Indigenous, who did the legwork on this first volume — I think it’s going to be the first volume of several volumes — to say that this is a widespread — this was a widespread, systematic destruction, not just of our culture but of our nations, as well as an open, you know, theft of land.

And I think that’s important to talk about here, that settler colonialism isn’t just about targeting Native people because they hate our culture, our language or our religion, but this boarding school system came at a time when the United States government, at the turn of the 19th century to the 20th century, was looking to consolidate its western frontier through the Dawes Allotment Act, which resulted in hundreds of millions of acres of Indian territory being opened up for white settlement and using Indian children as hostages. And that’s the language of the policy reformers at the time. That’s the language that they were using. They were saying, “We are going to use these children as hostages” for the, quote-unquote, “good behavior” of their people.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, you have visited and reported on one particular Indian boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that was opened in 1879. Can you talk about that as an example of what took place around this country?

NICK ESTES: Carlisle really became the archetype of off-reservation Indian boarding schools. And in fact, the Carlisle Indian School, the first classes that entered were from Lakota people, my nation, from specifically the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies, because we had put up a historic resistance against the Dawes Allotment Act, and it was a way to essentially break the tribal bonds of our people.

And so, that first class that went, it’s documented in Luther Standing Bear’s two autobiographies that he wrote. He’s from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. And he talks about these schools as not being so much schools, but as prisoner of war camps, where they learned — they didn’t learn, you know, the ABCs or language and mathematics, the things that you would expect to learn at schools. Instead, they learned military discipline, because General Pratt, or Colonel Pratt, he was a military man. And this was a strange arrangement between the U.S. military and the Department of Interior to run this off-reservation boarding school, but the militarized discipline became instilled in many of the off-reservation boarding schools, as well as the inculcation of U.S. patriotism, flag worship and religious obedience.

And so, the first classes that went to the Carlisle Indian School, according to the testimony of Luther Standing Bear, who was part of that first incoming class, half of them didn’t even return home. Many of them died at that school. So, it’s kind of a misnomer to actually call these educational institutions or schools themselves when you didn’t have very many people graduating, let alone surviving the dire conditions of those schools.

And in this report, they document the forced labor. The unpaid labor of Native children was used to essentially subsidize the lack of resources that the federal government was not providing to Indian education at this time, too. So it was a horrific experience for those who didn’t make it out, but it was also a horrific experience for those who did make it out.

And to this day, at the entrance of the Carlisle Indian School, there is a cemetery of hundreds of gravestones. And many tribal nations, including the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, have been working on returning their ancestors. Some of them have been successful. But it’s also important to point out that some of the children that died there are from tribal nations that don’t — you know, that have protocols around not disturbing their ancestors when they’re interred into the earth. And so this is a very delicate situation. It’s not just the problem of the federal government; it’s also the problem of the U.S. military.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let me ask —

NICK ESTES: Because this is an active — it’s an active military base. I think that’s important to point out, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Nick Estes, research by Preston McBride at Dartmouth, Dartmouth College, has suggested as many as 40,000 Native American children died at government-run boarding schools around the U.S. This report is saying 500. Can you talk more about this discrepancy?

NICK ESTES: Yeah, I think in the press briefing by the Department of Interior yesterday, it was pointed out by Deb Haaland, as well as Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland, that this was a preliminary report and that they’ve identified over 53 marked or unmarked gravesites at these various off-reservation boarding schools and on-reservation boarding schools. And I think it’s a really delicate matter, because, for example, the Rapid City Indian School, which is in Rapid City, South Dakota, the burial sites are actually within the community itself. There have been housing projects that had been built over the burial sites. And a lot of people are reluctant to identify them publicly because of the history of grave robbing at a lot of these sites. And so, I think what Preston is saying is very true, that this is an undercount, because it’s an initial survey of these specific gravesites. But I think as this investigation goes underway and more documents become available for the public, we’re going to see those numbers continue to rise. And it’s very tragic.

I think it’s important to point out that this initiative began last June, when several hundred Native children’s graves were found in Canada. But where are the headlines now about all the surveys that a lot of these First Nations are doing at these sites? And the numbers are in the thousands right now, but it’s not making headlines, you know? And so I think it’s important to pay attention to this as it unfolds and to really listen to a lot of the Native elders, as well as the Native researchers who have been doing this historically. This isn’t new news to us, you know. We don’t have a definitive number. All we have is the common experience of the boarding school system, as it has affected every single American Indian in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you have reservations about the report? In fact, it’s true the Interior Department report said they expect to find thousands, if not tens of thousands, of deaths. But you’re talking about a report that was released by the Interior Department and worked on by the Bureau of Indian Affairs within that, which actually ran the whole boarding school system. But the new development, of course, is Deb Haaland is in charge, the first Native American cabinet member in U.S. history.

NICK ESTES: Yeah, I think it’s important to point out that Deb Haaland is — you know, I think she’s been in this position for just over a year now. And one year, you know, in the face of a century and a half of genocidal Indian policy, isn’t that much, when we think about how history unfolds.

But also I think it’s important to point out that the perpetrator of this crime against humanity is now going to be the adjudicator of justice, so to speak. And there were questions of Deb Haaland’s office yesterday about what reparations will look like on behalf of tribes. They’re modeling their truth and reconciliation process off of the Canadian model. But it’s important to point out that the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission only came about because of a class-action lawsuit on behalf of residential school survivors. And I would say that the Department of Interior has a poor track record in terms of adjudicating an accounting for its own crimes.

You know, we can look at the Cobell settlement, which happened in 2011. You know, the — excuse me — the banker, Elouise Cobell, she was from the Blackfoot Nation. She did a forensic audit of the United States and found that the federal government had mismanaged $176 billion of individual Indian moneys, and the Department of Interior awarded itself, because we’re still considered wards of the government, $3.5 billion. That’s almost pennies on the dollar of what she had accounted for in terms of damages that we were awarded.

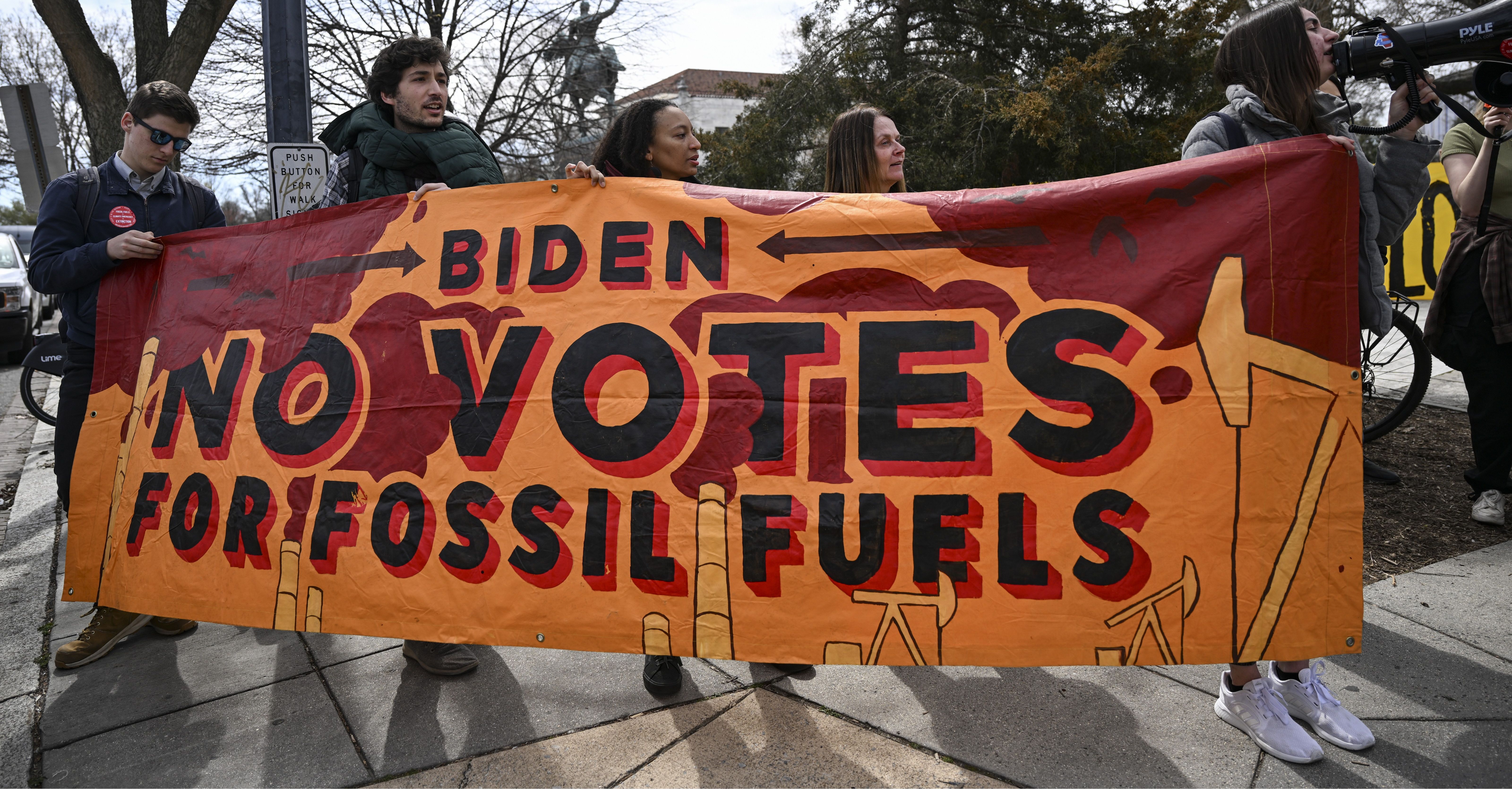

And so, it’s no coincidence that Indian people are in the same department that manages wildlife and federal lands. You know, we have — I heard earlier in the broadcast that the Department of Interior is kind of going back on this overt federal leasing program. But it’s not just the question of Indian boarding schools, you know, because Indian boarding schools were one facet of a larger process of dispossession and theft of Indigenous people’s lands and resources, because the Indian boarding school system was actually using treaty annuities and federal funds that was meant for Indian education for this genocidal process. And this money was gained through the selling of our land to white settlers. It was also gained through the dispossession of those lands by the federal government itself. And so there’s a lot of accounting to be done here.

And the report itself identifies 39,000 boxes of materials that the federal government has. I think it’s about 9 — over 9 million pages of documents that need to be reviewed. And so, allocating just $7 million to this investigative process over a century and a half of genocidal policies is kind of a drop in the bucket in what needs to happen. But it is important to point out that there is — Representative Sharice Davids, who’s a Democrat from Kansas and also from an Indigenous nation herself, has a bill that’s going through Congress right now that will open up, I think, more federal money for an investigative process that will look not only into the federal Indian boarding school system but also look into the role of faith groups, specifically the Catholic Church and its role in these genocidal educational policies.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we will certainly continue to follow all of this.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.

(@sunrisemvmt)

(@sunrisemvmt)