America’s federal public lands are truly unique, part of our birthright as citizens. No other country in the world has such a system.

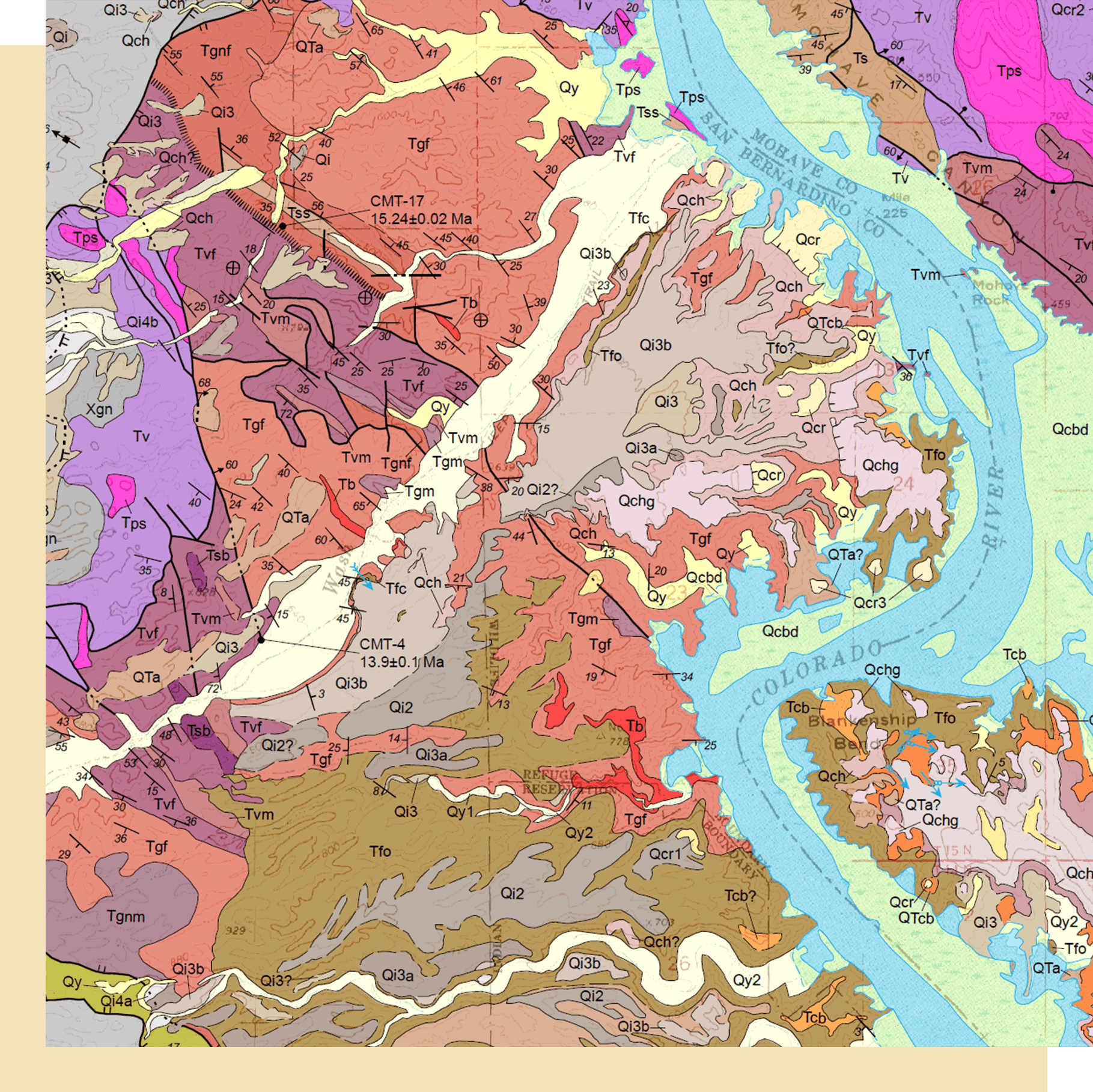

More than 640 million acres, including national parks, forests and wildlife refuges, as well as lands open to drilling, mining, logging and a variety of other uses, are managed by the federal government — but owned collectively by all American citizens. Together, these parcels make up more than a quarter of all land in the nation.

Congressman John Garamendi, a Democrat representing California, has called them “one of the greatest benefits of being an American.”

“Even if you don’t own a house or the latest computer on the market, you own Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and many other natural treasures,” he wrote in 2011.

Despite broad, bipartisan public support for protecting public lands, these shared landscapes have come under relentless attack during the first 100 days of President Donald Trump’s second term. The administration and its allies in Congress are working feverishly to tilt the scale away from natural resource protection and toward extraction, threatening a pillar of the nation’s identity and tradition of democratic governance.

“There’s no larger concentration of unappropriated wealth on this globe than exists in this country on our public lands,” said Jesse Duebel, executive director of the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, a conservation nonprofit. “The fact that there are interests that would like to monetize that, they’d like to liquidate it and turn it into cash money, is no surprise.”

Landscape protections and bedrock conservation laws are on the chopping block, as Trump and his team look to boost and fast-track drilling, mining, and logging across the federal estate. The administration and the GOP-controlled Congress are eyeing selling off federal lands, both for housing development and to help offset Trump’s tax and spending cuts. And the newly formed Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, led by billionaire Elon Musk, is wreaking havoc within federal land management agencies, pushing out thousands of civil servants. That purge will leave America’s natural heritage more vulnerable to the myriad threats they already face, including growing visitor numbers, climate change, wildfires, and invasive species.

The Republican campaign to undermine land management agencies and wrest control of public lands from the federal government is nothing new, dating back to the Sagebrush Rebellion movement of the 1970s and 80s, when support for privatizing or transferring federal lands to state control exploded across the West. But the speed and scope of the current attack, along with its disregard for the public’s support for safeguarding public lands, makes it more worrisome than previous iterations, several public land advocates and legal experts told Grist.

This is “probably the most significant moment since the Reagan administration in terms of privatization,” said Steven Davis, a political science professor at Edgewood College and the author of the 2018 book In Defense of Public Lands: The Case Against Privatization and Transfer. President Ronald Reagan was a self-proclaimed sagebrush rebel.

Duebel said the conservation community knew Trump’s return would trigger another drawn out fight for the future of public lands, but nothing could have prepared him for this level of chaos, particularly the effort to rid agencies of thousands of staffers.

The country is “in a much more pro-public lands position than we’ve been before,” Duebel said. “But I think we’re at greater risk than we’ve ever been before — not because the time is right in the eyes of the American people, but because we have an administration who could give two shits about what the American people want. That’s what’s got me scared.”

The Interior Department and the White House did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment.

In an article posted to the White House website on Earth Day, the Trump administration touted several “key actions” it has taken on the environment, including “protecting public lands” by opening more acres to energy development, “protecting wildlife” by pausing wind energy projects, and safeguarding forests by expanding logging. The accomplishment list received widespread condemnation from environmental, climate, and public land advocacy groups.

That same day, a leaked draft strategic plan revealed the Interior Department’s four-year vision for opening new federal lands to drilling and other extractive development, reducing the amount of federal land it manages by selling some for housing development and transferring other acres to state control, rolling back the boundaries of protected national monuments, and weakening bedrock environmental laws like the Endangered Species Act.

Meanwhile, Trump’s DOGE is in the process of cutting thousands of scientists and other staff from the various agencies that manage and protect public lands, including the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM. Nearly every Republican senator recently went on the record this month in support of selling off federal lands to reduce the federal deficit, voting down a measure that would have blocked such sales. And Utah has promised to continue its legal fight aimed at stripping more than 18 million acres of BLM lands within the state’s border from the federal government. Utah’s lawsuit, which the Supreme Court declined to hear in January, had the support of numerous Republican-led states, including North Dakota while current Interior Secretary Doug Burgum was still governor.

To advance its agenda, the Trump administration is citing a series of “emergencies” that close observers say are at best exaggerated, and at worst manufactured.

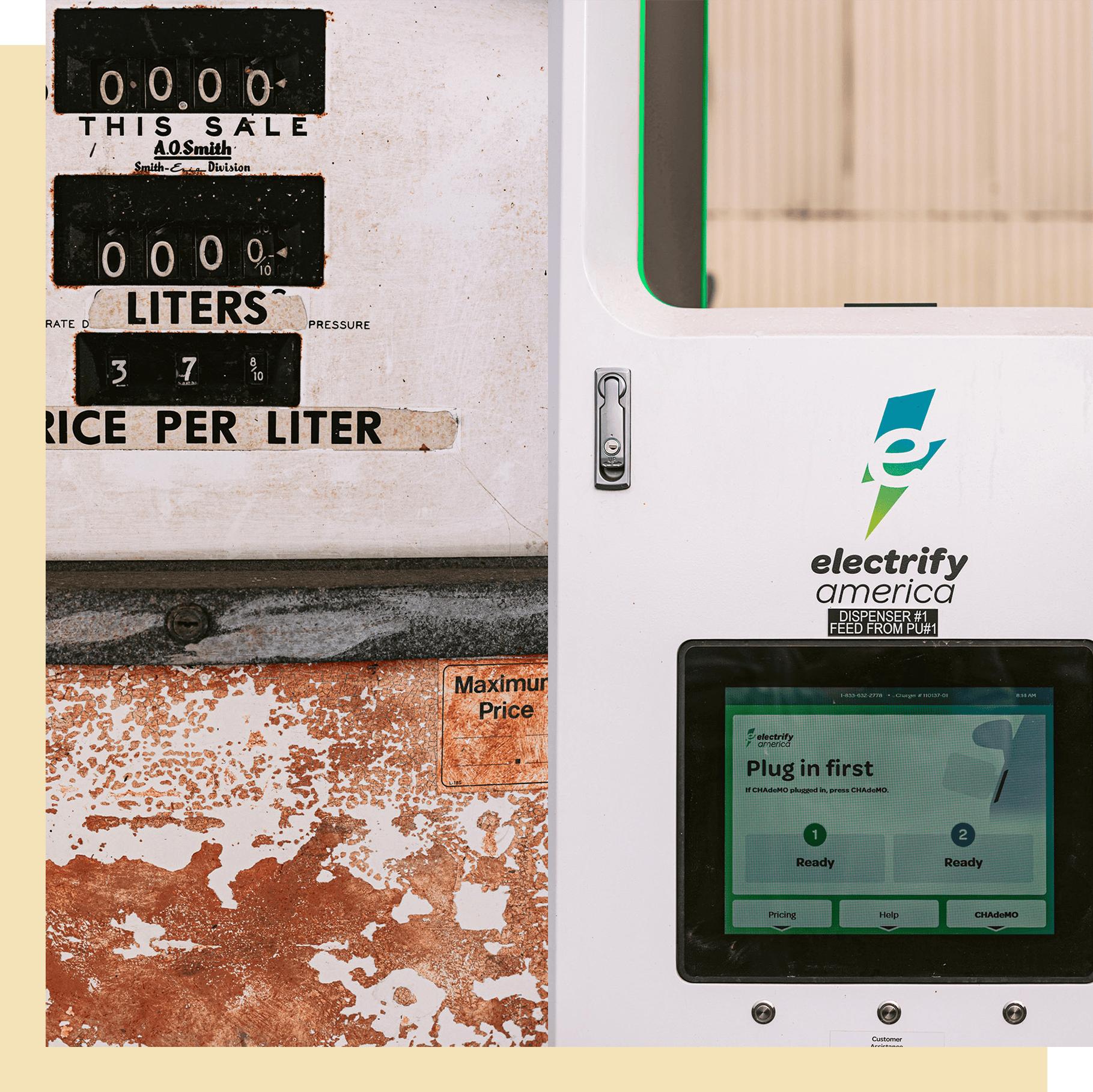

A purported “energy emergency,” which Trump declared in an executive order just hours after being inaugurated, has been the impetus for the administration attempting to throw longstanding federal permitting processes, public comment periods, and environmental safeguards to the wind. The action aims to boost fossil fuel extraction across federal lands and waters — despite domestic oil and gas production being at record highs — while simultaneously working to thwart renewable energy projects. Trump relied on that same “emergency” earlier this month when he ordered federal agencies to prop up America’s dwindling, polluting coal industry, which the president and his cabinet have insisted is “beautiful” and “clean.” In reality, coal is among the most polluting forms of energy.

“This whole idea of an emergency is ridiculous,” said Mark Squillace, a professor of natural resources law at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “And now this push to reinvigorate the coal industry seems absolutely crazy to me. Why would you try to reinvigorate a moribund industry that has been declining for the last decade or more? Makes no sense, it’s not going to happen.”

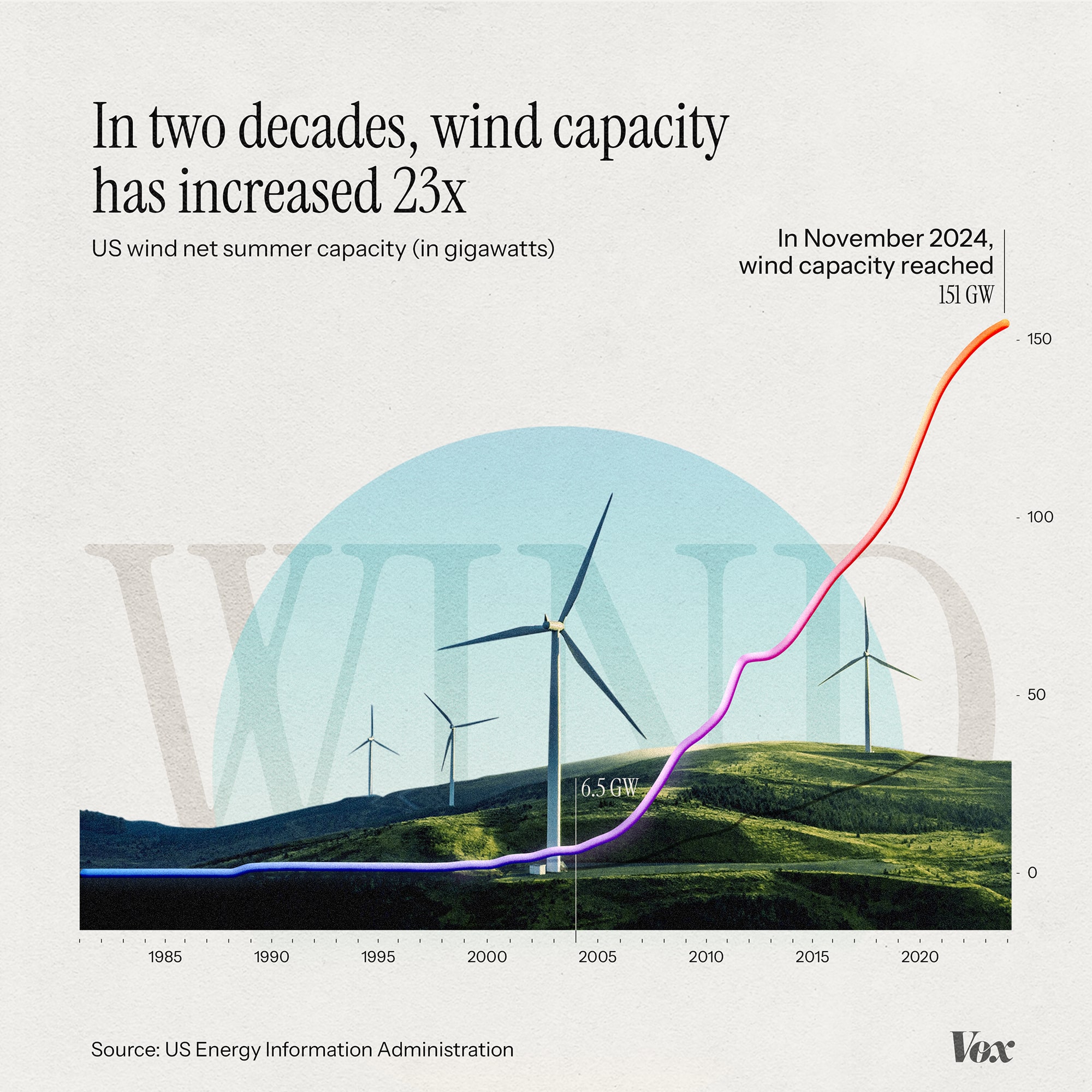

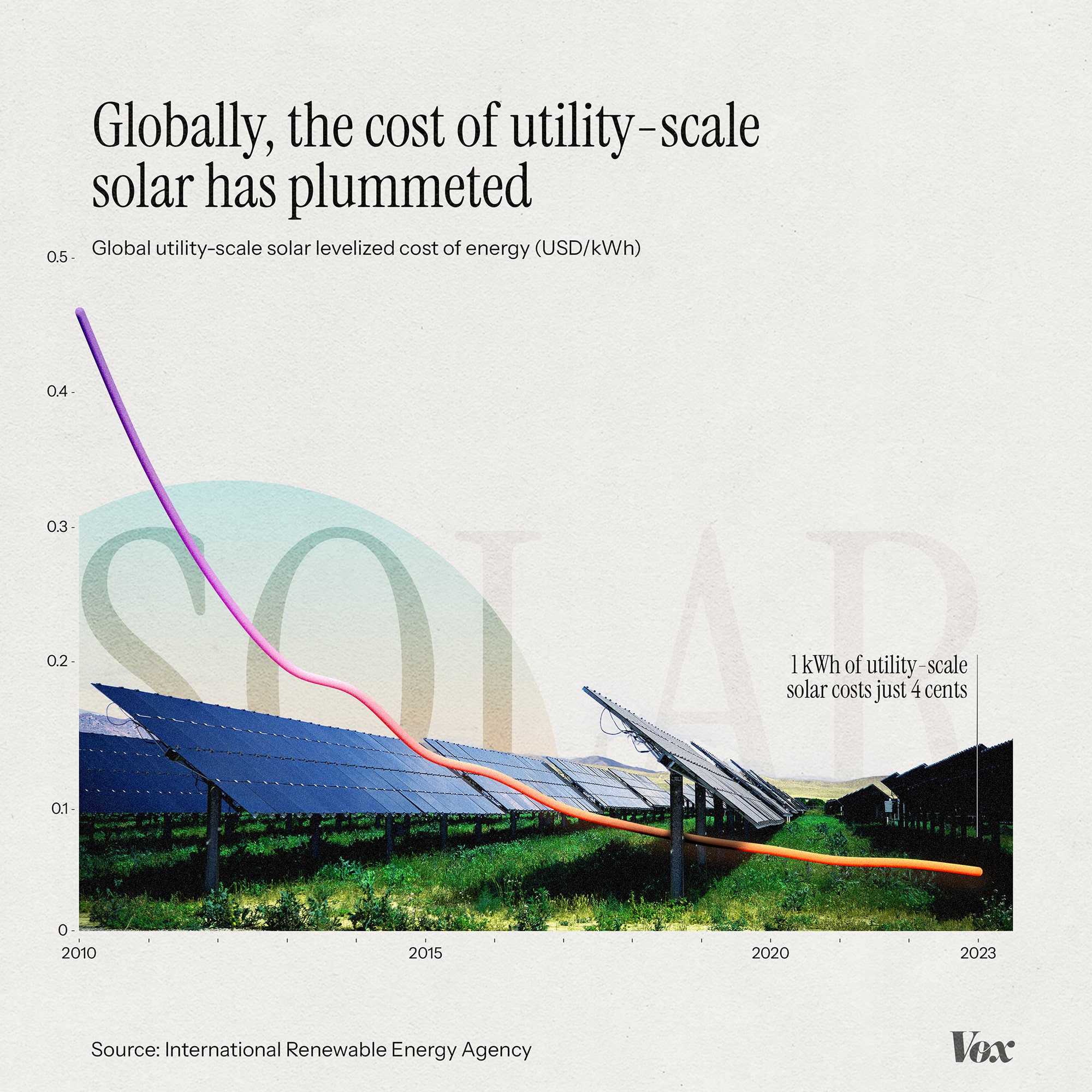

Coal consumption in the U.S. has declined more than 50 percent since peaking in 2005, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, largely due market forces, including the availability of cheaper natural gas and America’s growing renewable energy sector. Meanwhile, Trump’s tariff war threatens to undermine his own push to expand mining and fossil fuel drilling.

The threat of extreme wildfire — an actual crisis driven by a complex set of factors, including climate change, its role in intensifying droughts and pest outbreaks, and decades of fire suppression — is being cited to justify slashing environmental reviews to ramp up logging on public lands. Following up on a Trump executive order to increase domestic timber production, Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins signed a memo declaring a forest health “emergency” that would open nearly 60 percent of national forest lands, more than 110 million acres, to aggressive logging.

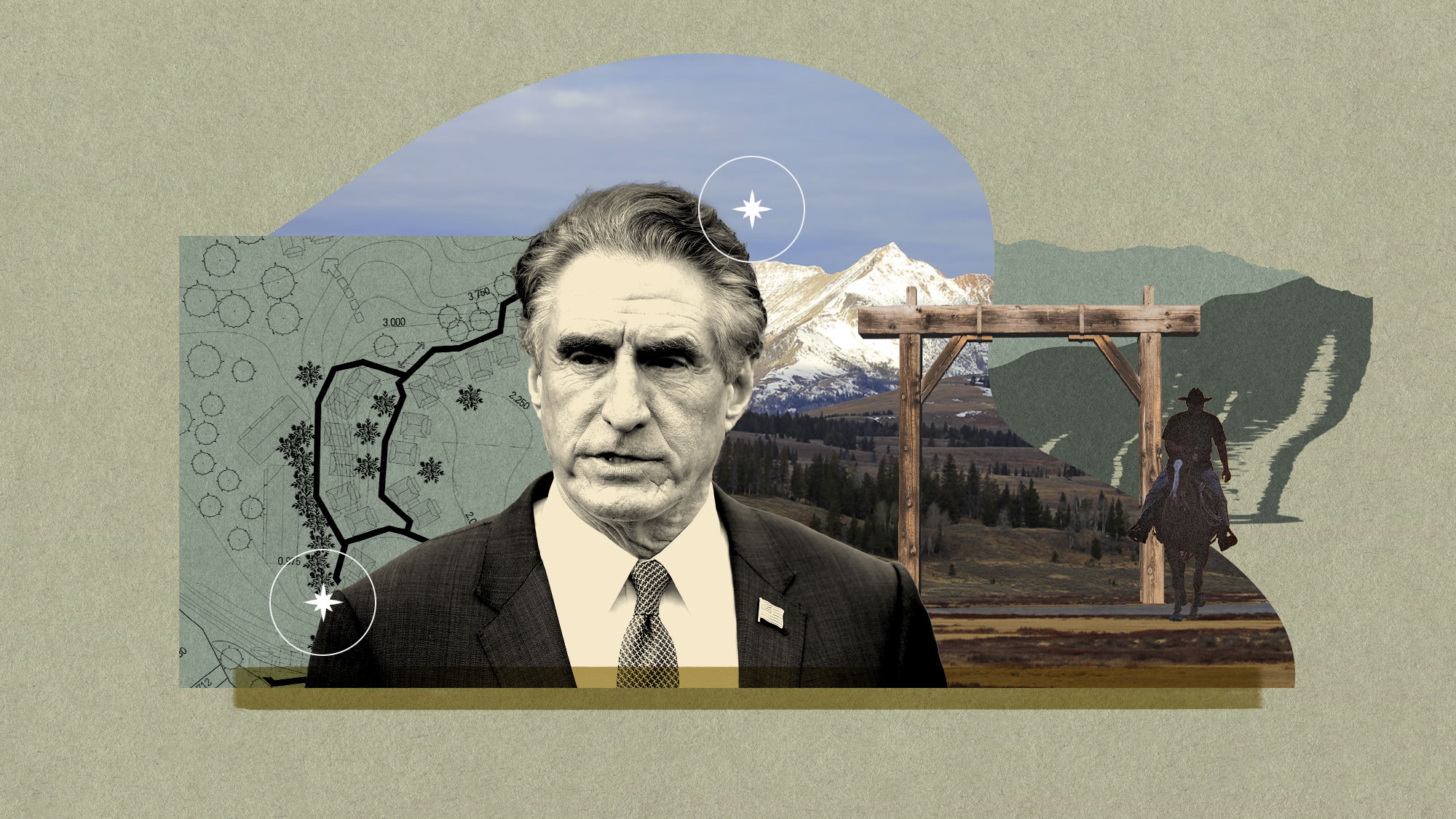

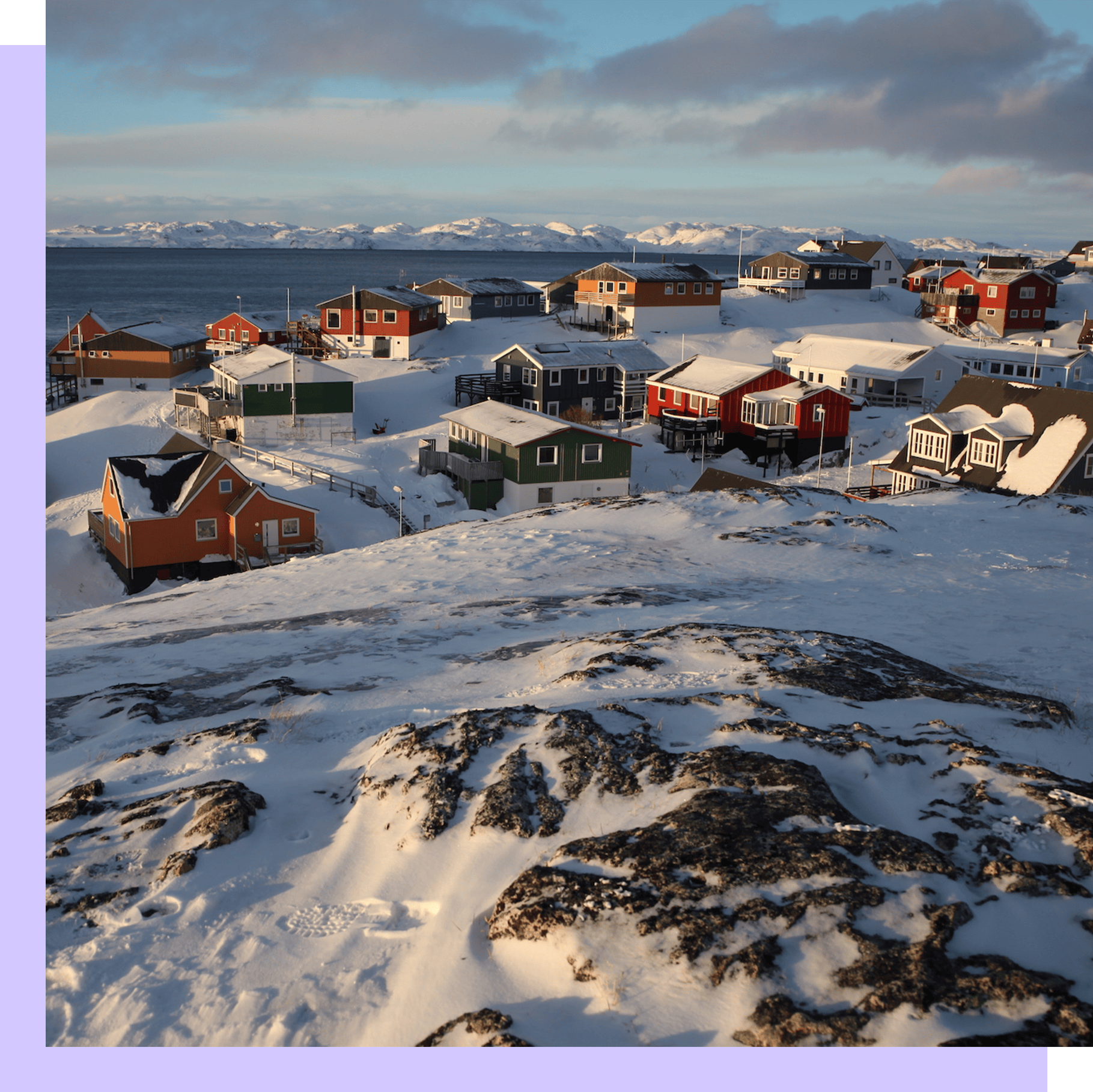

Then there’s America’s “housing affordability crisis,” which the Trump administration, dozens of Republicans, and even a handful of Democrats are pointing to in a growing push to open federal lands to housing development, either by selling land to private interests or transferring control to states. The Trump administration recently established a task force to identify what it calls “underutilized lands.” In an op-ed announcing that effort, Burgum and Scott Turner, secretary of Housing and Urban Development, wrote that “much of” the 500 million acres Interior oversees is “suitable for residential use.” Some of the most high-profile members of the anti-public lands movement, including William Perry Pendley, who served as acting director of the Bureau of Land Management during Trump’s first term, are championing the idea.

Without guardrails, critics argue the sale of public lands to build housing will lead to sprawl in remote, sensitive landscapes and do little, if anything, to address home affordability, as the issue is driven by several factors, including migration trends, stagnant wages, and higher construction costs. Notably, Trump’s tariff policies are expected to raise the average price of a new home by nearly $11,000.

Chris Hill, CEO of the Conservation Lands Foundation, a Colorado-based nonprofit working to protect BLM-managed lands, said the lack of affordable housing is a serious issue, but “we shouldn’t be fooled that the idea to sell off public lands is a solution.”

“The vast majority of public lands are just not suitable for any sort of housing development due to their remote locations, lack of access, and necessary infrastructure,” she said.

David Hayes, who served as deputy Interior secretary during the administrations of Barack Obama and Bill Clinton and as a senior climate adviser to President Joe Biden, told Grist that Trump’s broad use of executive power sets the current privatization push apart from previous efforts.

“Not only do you have the rhetoric and the intentionality around managing public lands in an aggressive way, but you have to couple that with what you’re seeing,” he said. “This administration is going farther than any other ever has to push the limits of executive power.”

Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a Colorado-based conservation group, said Trump and his team are doing everything they can to circumvent normal environmental rules and safeguards in order to advance their agenda, with no regard for the law or public opinion.

“Everything is an imagined crisis,” Weiss said.

Oil, gas, and coal jobs. Mining jobs. Timber jobs. Farming and ranching. Gas-powered cars and kitchen appliances. Even the water pressure in your shower. Ask the White House and the Republican Party and they’ll tell you Biden waged a war against all of it, and that voters gave Trump a mandate to reverse course.

During Trump’s first term in office, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke repeatedly boasted that the administration’s conservation legacy would rival that of his personal hero and America’s conservationist president, Theodore Roosevelt — only to have the late president’s great-grandson, Theodore Roosevelt IV, and the conservation community bemoan his record at the helm of the massive federal agency.

Like Zinke, Burgum invoked Roosevelt in pitching himself for the job.

“In our time, President Donald Trump’s energy dominance agenda can be America’s big stick that will be leveraged to achieve historic prosperity and world peace,” Burgum said during his confirmation hearing in January, referencing a 1990 letter in which the 26th president said to “speak softly and carry a big stick.”

The Senate confirmed him to the post in January on a bipartisan 79-18 vote. Some public land advocates initially viewed Burgum, now the chief steward of the federal lands, waters, and wildlife we all own, as a palatable nominee in a sea of problematic potential picks. A billionaire software entrepreneur and former North Dakota governor, Burgum has talked at length about his fondness for Roosevelt’s conservation legacy and the outdoors.

Whatever honeymoon there was didn’t last long. One-hundred days in, Burgum and the rest of Trump’s team have taken not a stick, but a wrecking ball to America’s public lands, waters, and wildlife. Earlier this month, the new CEO of REI said the outdoor retailer made “a mistake” in endorsing Burgum for the job and that the administration’s actions on public lands “are completely at odds with the longstanding values of REI.”

At an April 9 all-hands meeting of Interior employees, Burgum showed off pictures of himself touring oil and gas facilities, celebrated “clean coal,” and condemned burdensome government regulation. Burgum has repeatedly described federal lands as “America’s balance sheet” — “assets” that he estimates could be worth $100 trillion but that he argues Americans are getting a “low return” on.

“On the world’s largest balance sheet last year, the revenue that we pulled in was about $18 billion,” he said at the staffwide meeting, referring to money the government brings from lease fees and royalties from grazing, drilling, and logging on federal lands, as well as national park entrance fees. “Eighteen billion might seem like a big number. It’s not a big number if we’re managing $100 trillion in assets.”

In focusing solely on revenues generated from energy and other resource extraction, Burgum disregards that public lands are the foundation of a $1 trillion outdoor recreation economy, nevermind the numerous climate, environmental, cultural, and public health benefits.

Davis, the author of In Defense of Public Lands: The Case Against Privatization and Transfer, dismissed Burgum’s “balance sheet” argument as “shriveled” and “wrong.”

“You have to willfully be ignorant and ignore everything of value about those lands except their marketable commodity value to come up with that conclusion,” he said. When you add all their myriad values together, public lands “are the biggest bargain you can possibly imagine.”

Davis likes to compare public lands to libraries, schools, or the Department of Defense.

“There are certain things we as a society decide are important and we pay for it,” he said. “We call that public goods.”

The last time conservatives ventured down the public land privatization path, it didn’t go well.

Shortly after Trump’s first inauguration in 2017, then-Congressman Jason Chaffetz, a Republican representing Utah, introduced legislation to sell off 3.3 million acres of public land in 10 Western states that he said had “been deemed to serve no purpose for taxpayers.”

Public backlash was fierce. Chaffetz pulled the bill just two weeks later, citing concerns from his constituents. The episode, while brief, largely forced the anti-federal land movement back into the shadows. The first Trump administration continued to weaken safeguards for 35 million acres of federal lands — more than any other administration in history — and offered up millions more for oil and gas development, but stopped short of trying sell off or transfer large areas of the public domain.

Yet as the last few months have shown, the anti-public lands movement is alive and well.

Public land advocates are hopeful that the current push will flounder. They expect courts to strike down many of Trump’s environmental rollbacks, as they did during his first term. In recent weeks, crowds have rallied at numerous national parks and state capitol buildings to support keeping public lands in public hands. Democratic Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico, who voted to confirm Burgum to his post and serves as the ranking Democrat on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, has taken to social media to warn about the growing Republican effort to undermine, transfer and sell off public lands.

“I continue to be encouraged that people are going to be loud. They already are,” Deubel said. “We’re mobilizing. We’ve got business and industries. We’ve got Republicans, we’ve got Democrats. We’ve got hunters and we’ve got non-hunters. We’ve got everybody speaking out about this.”

In a time of extreme polarization on seemingly every issue, public lands enjoy broad bipartisan support. The 15th annual “Conservation in the West” poll found that 72 percent of voters in eight Western states support public lands conservation over increased energy development — the highest level of support in the poll’s history; 65 percent oppose giving states control over federal public lands, up from 56 percent in 2017; and 89 percent oppose shrinking or removing protections for national monuments, up from 80 percent in 2017. Even in Utah, where leaders have spent millions of taxpayer dollars promoting the state’s anti-federal lands lawsuit, support for protecting public lands remains high.

“Even in all these made up crises, the American public doesn’t want this,” Hill said. “The American people want and love their public lands.”

At his recent staffwide meeting, Burgum said Roosevelt’s legacy should guide Interior staff in its mission to manage and protect federal public lands. Those two things, management and protection, “must be held in balance,” Burgum stressed.

Yet in social media posts and friendly interviews with conservative media, Burgum has left little doubt about where his priorities lie, repeatedly rolling out what Breitbart dubbed the “four babies” of Trump’s energy dominance agenda: “Drill, Baby, Drill! Map, Baby, Map! Mine, Baby, Mine! Build, Baby, Build!”

“Protect, baby, protect,” “conserve, baby, conserve,” and “steward, baby, steward” have yet to make it into Burgum’s lexicon.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The Trump administration’s push to privatize US public lands on Apr 29, 2025.

This post was originally published on Grist.