This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

This content originally appeared on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and was authored by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

It has been suggested that to reduce landfill greenhouse gas emissions, food wastes should be ground up and sent to the sewer. This is the worst possible attempt to reduce greenhouse gases, and will, in fact, increase the amount of greenhouse gases released to process those food wastes.

I have worked at a wastewater treatment plant for the last five years. These facilities are located in every small, medium and large city, with public sewer systems, across the world. They are designed to process human fecal waste, capture organic matter and metals, and release treated water back into the environment. They primarily process those wastes using a biological system of bacteria and microorganisms.

Heavy particles or debris that come in with the wastewater will be filtered or collected at the front of the plant and taken to a landfill. That filtration or collection requires energy. That energy is provided with electricity, often created by burning fossil fuels.

Any lighter particles that stay suspended in water or float on the surface will also be collected. Any carbon will be converted into methane by bacteria in an anaerobic digester or processed by bacteria into carbon dioxide in an aeration basin. Either solution also requires additional energy, either to heat the anaerobic digesters or to pump air into the water to add oxygen to it.

The amount of carbon coming into the treatment plant will exactly equal the amount going out as carbon dioxide, methane or as sewage sludge. Sewage sludge is the leftover solids, bacteria and organic matter that will need to be removed from the treatment plant. The sludge will either be land applied on farms as fertilizer, or sent to a landfill. As regulations tighten on land application across the world, landfills will be the ultimate destination of all sewage sludge in the near future.

The food waste you send down the drain, instead of throwing it into the garbage, will ultimately still end up at the landfill. The carbon in that food will still be released as methane or carbon dioxide. Except, instead of the two steps of collection and delivery to the landfill, it will compound the effects of that food waste by sending it through a wastewater treatment plant, increasing the energy costs of the treatment plant and increasing the amount of greenhouse gases released to process that food waste.

If you want to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases from your food waste, compost it or turn it into biochar by burning it in a low heat environment with a lack of oxygen. That is the only way to lock in the carbon for long term storage. Don’t send excess food wastes to a treatment plant, we have enough carbon to deal with, just with the feces.

The post Wasting Food first appeared on Dissident Voice.This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.

Some of the votes Americans cast on Tuesday that may have mattered most for the climate were quite a bit downballot from the presidential ticket: A handful of states held elections for the commissions that regulate utilities, and thereby exercise direct control over what sort of energy mix will fuel the coming years’ expected growth in electricity demand. In three closely watched races around the country — the utility commissions in Arizona, Montana, and Louisiana — Republican candidates either won or are in the lead. While they generally pitched themselves to voters as market-friendly, favoring an all-of-the-above approach to energy, clean energy advocates interviewed by Grist cast these candidates as deferential to the power companies they aspired to regulate.

Arizona is, in a word, sunny. Its geography makes it “the famously obvious place to build solar,” said Caroline Spears, executive director of Climate Cabinet, a nonprofit that works to get clean energy advocates elected. But its utilities have built just a sliver of the potential solar energy that there is room for in the state — and the Arizona Corporation Commission, which regulates the state’s investor-owned utilities, is partly to blame for that. That commission’s most recent goal for renewable energy, set in 2007, was an unambitious 15 percent to be reached by 2025. “Their goals are worse than where Texas currently is and where Iowa currently is on clean energy,” Spears said. What’s more, the current slate of commissioners is in the process of considering whether to ditch that goal altogether.

Those commissioners have held a 4-1 Republican majority on the commission since 2022, and in that time they’ve approved the construction of new gas plants, imposed new fees on rooftop solar, and raised electricity rates. Tuesday’s election, in which three of the commission’s five seats were on the ballot, gave voters a chance to reverse course. The race hasn’t yet been officially called, but three Republican candidates are in the lead, ahead of three Democratic candidates, two Green candidates, and a write-in independent. (The election is structured such that candidates don’t run for individual seats or in districts; rather, the seats go to the three top vote-getters.)

So far, the Republican candidate who’s gotten the most votes is Rachel Walden, a member of the Mesa school board who’s made a name for herself in Arizona politics with transphobic comments and a failed lawsuit against the Mesa school district over its policies on student bathroom usage. “She’s a candidate who doesn’t have a lot of specific energy experience but seems to be very diehard to the kind of MAGA movement more broadly,” said Stephanie Chase, a researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, a utility watchdog nonprofit.

In Montana, three seats were open on the Public Service Commission, but one in particular — District 4 — captured the attention of clean energy advocates, because it was the only one in which a non-Republican candidate was running. Elena Evans, an independent, began her campaign after learning that the incumbent commissioner in her district, Jennifer Fielder, was running unopposed. The race focused less on clean energy than affordability: Evans said in interviews she decided to run because of the 28 percent rate hike that the all-Republican commission had approved. In the closest of the commission’s three elections, Fielder beat Evans with 55 percent of the vote.

Like in Arizona, the Montana PSC has neglected to take advantage of its state’s untapped potential for renewable energy — wind. A Montana commissioner was captured on a hot mic in 2019 candidly acknowledging that the purpose of a rate cut for renewable energy providers was to kill solar development in the state.

While one independent on the commission wouldn’t have likely swayed the course of its decisions, Evans would have had the opportunity “to be a consumer voice,” in Chase’s words, as the commission deliberated not only over future decisions on renewable energy, but also the looming question of the future of a coal plant in eastern Montana. The Colstrip power plant has been co-owned by utilities in nearby states, which, in anticipation of those states’ renewable energy targets kicking in, are selling their shares of its energy to the Montana utility NorthWestern Energy. These deals could saddle ratepayers in Montana with new costs, both for the purchase and for compliance with environmental regulations.

In Louisiana, the largest utility regulated by the Public Service Commission is Entergy, which Daniel Tait, a researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, described as “one of the most reviled utilities in the country by its customers.” Louisiana’s utilities are legally permitted to donate directly to the campaign funds for commissioners who regulate them — and they do so in great volume.

The race to replace Louisiana Public Service Commissioner Craig Greene, who is retiring at the end of his term, commanded attention because, though a Republican representing a deep-red part of the state, Greene is considered the swing vote among the five commissioners, two of whom are Democrats. In his eight years in office, he’s become known for “his willingness to hold Entergy accountable,” according to Tait — voting with the progressive commissioner Davante Lewis on issues like energy efficiency programs and limiting utilities’ political spending.

On Tuesday, Greene’s seat was won by Jean-Paul Coussan, a state senator from Lafayette who accepted utility donations, supports an expansion of gas infrastructure, and has criticized renewables for “driv[ing] out oil and gas jobs.” Tait described Coussan as less hostile to clean energy than his Republican opponent in the race, Julie Quinn, but further right than the Democrat he defeated, Nick Laborde.

In an interview with the Louisiana Illuminator, Coussan cast his energy policies as based on free markets. “It’s critical that we look at the most affordable options. I think renewables are currently part of the matrix and will be in the future,” he said. “We also need to address the reality that we’ve got an abundant supply of natural gas.”

Coussan has also spoken of the needs of Louisianans who are suffering from repeated hurricanes and rising rates. “The things that he has said since being elected are contradictory in nature,” Tait said of Coussan. “He says he wants affordable and reliable energy, and that he cares about storm protection, because there are so many issues in Louisiana, but the very thing that’s creating these storms is climate change — which is being caused by carbon emissions.”

“You can’t make the problem worse and say you want to work hard to solve the problem,” Tait added.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline These downballot elections may slow the shift to clean energy on Nov 8, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Donald J. Trump will once again be president of the United States.

The Associated Press called the race for Trump early Wednesday morning, ending one of the costliest and most turbulent campaign cycles in the nation’s history. The results promise to upend U.S. climate policy: In addition to returning a climate denier to the White House, voters also gave Republicans control of the Senate, laying the groundwork for attacks on everything from electric vehicles to clean energy funding and bolstering support for the fossil fuel industry.

“We have more liquid gold than any country in the world,” Trump said during his victory speech, referring to domestic oil and gas potential. The CEO of the American Petroleum Institute issued a statement saying that “energy was on the ballot, and voters sent a clear signal that they want choices, not mandates.”

The election results rattled climate policy experts and environmental advocates. The president-elect has called climate change “a hoax” and during his most recent campaign vowed to expand fossil fuel production, roll back environmental regulations, and eliminate federal support for clean energy. He has also said he would scuttle the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which is the largest investment in climate action in U.S. history and a landmark legislative win for the Biden administration. Such steps would add billions of tons of additional greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and hasten the looming impacts of climate change.

“This is a dark day,” Ben Jealous, the executive director of the Sierra Club, said in a statement. “Donald Trump was a disaster for climate progress during his first term, and everything he’s said and done since suggests he’s eager to do even more damage this time.”

During his first stint in office, Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement, the 2016 international climate accord that guides the actions of more than 195 countries, rolled back 100-plus environmental rules, and opened the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. While President Joe Biden reversed many of those actions and made fighting climate change a centerpiece of his presidency, Trump has pledged to undo those efforts during his second term with potentially enormous implications — climate analysts at Carbon Brief predicted that another four years of Trump would lead to the nation emitting an additional 4 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide than it would under his opponent. That’s on par with the combined annual emissions of the European Union and Japan.

One of president-elect Trump’s primary targets will be rolling back the IRA, which is poised to direct more than a trillion dollars into climate-friendly initiatives. Two years into that decade-long effort, money is flowing into myriad initiatives, ranging from building out the nation’s electric vehicle charging network to helping people go solar and weatherize their homes. In 2023 alone, some 3.4 million Americans claimed more $8 billion in tax credits the law provides for home energy improvements. But Trump could stymie, freeze, or even eliminate much of the law.

“We will rescind all unspent funds,” Trump assured the audience in a September speech at the Economic Club of New York. Last month, he said it would be “an honor” to “immediately terminate” a law he called the “Green New Scam.”

Such a move would, however, require congressional support. While many House races remain too close to call, Republicans have taken control of the Senate. That said, any attempt to roll back the IRA may prove unpopular, however, because as much as $165 billion in the funding it provides is flowing to Republican districts.

Still, Trump can take unilateral steps to slow spending, and use federal regulatory powers to further hamper the rollout process. As Axios noted, “If Trump wants to shut off the IRA spigot, he’ll likely find ways to do it.” Looking beyond that seminal climate law, Trump has plenty of other levers he can also pull that will adversely affect the environment — efforts that will be easier with a conservative Supreme Court that has already undermined federal climate action.

Trump has also thrown his support behind expanded fossil fuel production. He has long pushed for the country to “drill, baby, drill” and, in April, offered industry executives tax and regulatory favors in exchange for $1 billion in campaign support. Though that astronomical sum never materialized, The New York Times found that oil and gas interests donated an estimated $75 million to Trump’s campaign, the Republican National Committee, and affiliated committees. Fossil fuels were already booming under Biden, with domestic oil production higher than ever before, and Vice President Kamala Harris said she would continue producing them if she won. But Trump could give the industry a considerable boost by, for instance, re-opening more of the Arctic to drilling.

Any climate chaos that Trump sows is sure to extend beyond the United States. The president-elect could attempt to once again abandon the Paris Agreement, undermining global efforts to address the crisis. His threat to use tariffs to protect U.S. companies and restore American manufacturing could upend energy markets. The vast majority of solar panels and electric vehicle batteries, for example, are made overseas and the prices of those imports, as well as other clean-energy technology, could soar. U.S. liquified natural gas producers worry that retaliatory tariffs could hamper their business.

The Trump administration could also take quieter steps to shape climate policy, from further divorcing federal research functions from their rulemaking capacities to guiding how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studies and responds to health concerns.

Trump is all but sure to wreak havoc on federal agencies central to understanding, and combatting, climate change. During his first term, his administration gutted funding for research, appointed climate skeptics and industry insiders, and eliminated several scientific advisory committees. It also censored scientific data on government websites and tried to undermine the findings of the National Climate Assessment, the government’s scientific report on the risks and impacts of climate change to the country. Project 2025, the sweeping blueprint developed by conservative groups and former Trump administration officials, advances a similar strategy, deprioritizing climate science and perhaps restructuring or eliminating federal agencies that advance it.

“The nation and world can expect the incoming Trump administration to take a wrecking ball to global climate diplomacy,” Rachel Cleetus, the policy director and lead economist for the Climate and Energy Program at the Union for Concerned Scientists, said in a statement. “The science on climate change is unforgiving, with every year of delay locking in more costs and more irreversible changes, and everyday people paying the steepest price.”

The president-elect’s supporters seem eager to begin their work.

Mandy Gunasekara, a former chief of staff of the Environmental Protection Agency during Trump’s first term, told CNN before the election that this second administration would be far more prepared to enact its agenda, and would act quickly. One likely early target will be Biden-era tailpipe emissions rules that Trump has derided as an electric vehicle “mandate.”

During his first term, Trump similarly tried to weaken Obama-era emissions regulations. But the auto industry made the point moot when it sidestepped the federal government and made a deal with states directly, a move that’s indicative of the approach that environmentalists might take during his second term. Even before the election, climate advocates had begun preparing for the possibility of a second Trump presidency and the nation’s abandoning the global diplomatic stage on this issue. Bloomberg reported that officials and former diplomats have been convening secret conversations, crisis simulations, and “political wargaming” aimed at maximizing climate progress under Trump — an effort that will surely start when COP29 kicks off next week in Baku, Azerbaijan.

“The result from this election will be seen as a major blow to global climate action,” Christiana Figueres, the United Nations climate chief from 2010 to 2016, in a statement. “[But] there is an antidote to doom and despair. It’s action on the ground, and it’s happening in all corners of the Earth“

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The massive consequences Trump’s re-election could have on climate change on Nov 6, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

The U.S. power grid is at a critical crossroads. Electricity generation, like every other industry, needs to rid itself of fossil fuels if the country is to play its role in combating the climate crisis — a transition that will have to happen even as energy providers scramble to meet what they claim is an unprecedented spike in electricity demand, attributed to the rise of AI.

Considered as a physical object, the North American grid is the world’s largest machine; in its political form in the United States, however, it’s a mess of overlapping jurisdictions. So whether the country meets this newly rising demand for electricity in a climate-friendly way or by prolonging the fossil fuel industry’s dominance will largely be up to the 200 or so regulators who sit on state utility commissions. No single person or body of government is in the driver’s seat — the humble, arcane, and largely out-of-sight utility commissions are in control of the grid and its future. Their mandate is to approve or deny the utility companies’ expenditures and the rates they collect from their customers to pay for them. This means federal policymakers can implement all the incentives they want for clean energy, but these efforts will amount to nothing if state-level regulators don’t require utilities to build it.

Every state has a regulatory panel known variously as a public utilities commission, public service commission, corporation commission, or even railroad commission. Most are appointed, typically by the governor. In 10 states, utility regulators are directly elected by voters. Eight of those states are holding elections for at least one seat on November 5.

Three seats on Arizona’s utility commission (known as the Arizona Corporation Commission) are up for grabs. In the short time that body has had a 4-1 Republican majority, it’s gone on a spree of approving the construction of new gas plants, alongside rate hikes and new fees for rooftop solar installations. In Louisiana, a Republican commissioner is retiring, and the choice of his replacement is pivotal because he has been the commission’s lone swing vote. And on the Montana Public Service Commission, which is currently entirely Republican, Tuesday’s election will prove a test of voters’ dissatisfaction with the 28 percent rate hike approved for customers of the state’s largest energy company last year. The results of these elections — and the makeup of commissions across the country, elected and appointed — will quite literally determine whether states add more fossil fuel capacity or transition to clean fuel sources over the next several years, driving how quickly the U.S. cuts emissions nationwide.

How did state utility commissions get so much power? And what can they do with it in this pivotal moment?

For decades after General Electric — the company at the leading edge of electrifying society — was founded in 1892, electricity remained a high-cost luxury. Most people who could afford electricity service, in urban centers like New York City and Boston, were customers of utilities owned by their local municipality. Samuel Insull, an enterprising Brit who started his career as Thomas Edison’s secretary, sought to change that by distributing electricity more widely and selling it more cheaply. In 1912, Insull founded the Middle West Utilities Company, a holding company based in Chicago; because Middle West owned and controlled smaller and more local subsidiaries throughout the region, it gave Insull the reach, and capital, to pioneer centralized power plants that operated nonstop.

In order to advance his own dominance, Insull was a forceful advocate for an agreement between the privately owned utility companies and state regulators that recognized the utilities’ “natural monopoly” over electricity. It doesn’t make sense, the argument went, for power companies to compete over who serves a given customer; it would be “wasteful duplication” for multiple transmission lines to power the same cities and try to outbid one another on rates. In exchange for legal protection of their monopoly, the companies would submit to the oversight of public utility commissions, or PUCs. It was a transference of the regulatory structure that had already been instituted in response to the construction of the railroad industry that accelerated the settlement of the West in the second half of the 19th century. (The public utilities commission in Texas is still called the Texas Railroad Commission, even though it’s been decades since it had anything to do with trains.) Insull’s vision came to dominate the regulatory landscape for electricity in the first two decades of the 20th century, and a handful of large holding companies took control over power generation and distribution nationwide.

In practice, the model was imperfect. The commissions were susceptible to corruption (the concept of “regulatory capture,” a phenomenon in which agencies become influenced by the industries they regulate, was first applied to utility regulation). In a series of Federal Trade Commission investigations beginning in the late 1920s, the electricity industry was revealed to be rife with financial fraud. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Public Utility Holding Company Act, a law restricting utility holding companies from exercising monopolies across multiple states and authorizing the Securities and Exchange Commission to break up utility monopolies as it saw fit. Middle West collapsed in the wake of greater government scrutiny and the Great Depression, and the political fortunes of the monopoly model waned.

Still, the structure of vertically integrated monopoly utilities generally persisted until liberalizing reforms in the 1990s prohibited one company from controlling the generation, transmission, and distribution of power, and created wholesale electricity markets where power is auctioned from power plants to customers. In areas with wholesale markets — called regional transmission organizations, known as RTOs, or independent system operators — economic forces and real-time price auctions combine with the priorities of utility commissions to influence both what types of power generation get built and how much energy costs for customers. The specifics of each market vary: Some areas allow consumers to choose their electricity operator from an array of options, for instance, while others allow utilities to maintain their territorial monopolies and participate in regional marketplaces with the energy they make. But utility commissions still play a critical role in approving those utilities’ rates, construction of power plants and transmission lines, and long-term plans. The commissions can also require the utilities in their jurisdiction to take critical steps toward improving equity or expanding renewable energy.

Such markets exist in almost all of the country, save the Southeast, where the makers and sellers of electricity operate with legally protected monopolies in their service territories. If you live in Georgia, Alabama, or Mississippi, for instance, your location within the state determines which power company is available to you, and the utility commission is the primary check on its rates and operations. Because of these utilities’ unique financial structure, with a fixed return on any capital investment guaranteed to their shareholders by the local utility commission, they are better incentivized to build large, capital-intensive energy infrastructure like nuclear plants and offshore wind turbines. That’s put these protected monopolies in the spotlight as they figure out how to respond to the demands of the moment: “The decisions that Southeastern PUC commissioners make over the next three years will make or break whether the U.S. meets the energy transition objectives and, by extension, the world,” said Charles Hua, founder of the organization PowerLines, which is seeking to modernize utility regulation in the U.S. But utility commissions are not only consequential in that region.

While people in those three states deal directly with their respective power company, some of the largest utilities in those states — Georgia Power, Alabama Power, and Mississippi Power — are actually owned by the same company, the Southern Company. In 2005, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, which repealed Roosevelt’s Public Utility Holding Company Act and, as the journalist Kate Aronoff has written, “helped to clear the way for the reemergence of the type of holding companies that inspired it in the first place, with entities like Southern Company having spawned new arms that exist in something of a regulatory gray area.”

Electricity generation is responsible for a quarter of America’s greenhouse gas emissions, and undergirds much of the rest; decarbonizing energy is an essential component of any serious climate plan. If the country’s grid is ever weaned off of fossil fuels, federal policy will no doubt play a crucial role. But the federal government’s ability to make that happen with the tools it is using — primarily, under the Biden administration, subsidies intended to make low-carbon electricity profitable — is limited. The decision to actually build renewable energy generation occurs at the state level.

“We need to make sure that we do this right,” said Hua, of the current moment in energy transition. “And by that, what we mean is to center the public interest so that the public and consumers come out of this transition better off.”

While utilities are typically the ones who put forward plans for their regulators to approve, deny, or amend, the commissioners often have substantial latitude to make changes — or even outright order utilities to pursue certain types of energy. In Georgia, for instance, individual commissioners have directed the state’s largest utility, Georgia Power, to add solar and biomass to its portfolio; the former has helped the state climb to seventh in the country for utility-scale solar, while the latter led to the controversial approval of a new biomass plant expected to increase customers’ bills. Minnesota’s commission issued an order directing utilities to maximize their use of benefits from the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark climate law that contains subsidies for utilities who add renewable energy.

Utility commissions have a substantial influence even on renewable energy that’s owned by individuals — that is, rooftop solar. It’s impossible for most homeowners or businesses to go fully off the grid, because those systems typically generate more power than the owner needs when it’s sunny, and the user still needs energy at night. Batteries can help, but rooftop solar users typically need to both buy and sell electricity — a contract with their utility that the state’s commission oversees. The terms of these deals have far-reaching implications for how much rooftop solar costs and, by extension, how many people use it. When California’s utility commission cut the rate utilities pay customers for their solar energy, rooftop installations plummeted.

An alternate model is in place in the areas served by the Tennessee Valley Authority, a federal agency created during the New Deal. The TVA provides power to customers in seven Southern states, including most of Tennessee, and is overseen by a board nominated by the U.S. president. Its lack of a profit motive has enabled it to respond somewhat differently to the recent growth in projected electricity demand spikes caused by new data centers.

Like its neighbors in the Southeast, the TVA is “building an insane amount of gas — but they’re spending more money on energy efficiency and demand response than any other utility” in the region, said Daniel Tait, a researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, a nonprofit utility watchdog. For the TVA, unlike utilities that primarily profit off of the construction of new infrastructure, “a kilowatt-hour from a gas plant versus from energy efficiency should be no different to them, because they make no money,” Tait said. Clean energy advocates have long been pushing for utility commissions to consider energy efficiency in the same way, with mixed results.

One point analysts agree on is that no regulatory structure is completely winning the energy transition — the grass, it seems, is often greener in someone else’s service territory. Advocates working with vertically integrated monopolies, for instance, argue the lack of a competitive market keeps newer technologies, especially renewables, from thriving because growth is limited to what the individual utility agrees to build.

Energy analysts working on RTOs worry that the more liberalized markets don’t do enough centralized, concerted planning, which can create reliability issues. Critics also contend that RTOs often face less public accountability than monopoly utilities, which are more fully subject to elected or appointed utility commissions that hold public meetings — provided, of course, that ratepayers and stakeholders hold their utilities and commissions accountable.

“If we could wave a magic wand and tomorrow everybody knew that three or five or seven people determine their energy bills, we think that would be a good thing,” Hua said.

How exactly to get people engaged with their utility commission in the absence of a magic wand is a persistent challenge for clean energy and consumer advocates. Mostly, they try to educate their supporters with blog posts and newsletters highlighting a commission’s actions or votes, or the group’s own advocacy work. Some states have even established advisory councils and launched public engagement initiatives. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, created an Office of Public Participation in 2021 to help educate the public and encourage engagement; while it’s focused on FERC proceedings, the office’s materials also provide basic information and terminology to understand the complicated world of energy regulation.

Beyond getting involved in the process, individuals can also influence the makeup of the commissions themselves. While that opportunity is most obvious in the states that directly elect their commissioners, elections and public pressure can drive change in states with appointed commissions too. In Massachusetts, Democratic Governor Maura Healy replaced commissioners on her state’s utility commission soon after she took office. The new commission has since opened a docket on low-income energy burdens, taken steps to improve equitable access to solar energy, and overseen utilities’ clean energy roadmaps required by a 2022 state law. And last year, in Maryland, a gas industry executive nominated by the governor withdrew his candidacy for the state’s public service commission after outcry from environmental groups.

Commissioners themselves also have some ability to reimagine their roles.

“In this time and moment we should be asking ourselves, ‘How can we be innovative?’ instead of doubling down and doing what we’ve done the last hundred years every time there’s load growth,” said Davante Lewis, a progressive utility commissioner in Louisiana who was elected in 2022.

Primarily, Lewis suggests that regulators take “environmental concerns and the ecosystem” into consideration. “Typically the regulatory compact has been solely decided based on whether or not a utility is justified in building something,” Lewis said. “We need a more comprehensive, holistic view: Not only was this the most prudent decision financially; is it the most prudent decision environmentally?”

Utility commissions often have enough latitude under state law to examine factors beyond price and reliability, according to a University of Michigan Law School analysis, but many are hesitant to do so. That’s where a state legislature can step in to expand the commission’s scope. Colorado, for instance, has broadened its utility commission’s authority to explicitly include equity, including minimizing the negative impacts of its decisions and addressing historic inequalities — a change the commission’s staff called a “new decision-making paradigm.” The staff’s report on how to implement the new rule recommends requiring utilities to develop equity plans and creating a new type of proceeding to consider the equity impact of electric and gas issues. Since a major critique of gas and coal plants is the negative effects of their pollution on the often-marginalized communities nearby, the process, if implemented, could significantly influence decisions about such power plants.

Other states have tried to even the playing field between electric utilities and the other stakeholders who weigh in on their plans before utility commissions. Large, investor-owned utilities employ large staffs of lawyers and experts who can testify on their behalf. Environmental and consumer advocates, meanwhile, are typically nonprofits with much smaller budgets, which can make it difficult for them to hire or contract with experts to make their case for renewable energy, lower rates, and other policies against a mountain of testimony and data from the utility.

“There can be an extreme imbalance between the different parties who might be participating in these proceedings,” said Oliver Tully, the director of utility innovation and reform for the Acadia Center, a nonprofit advocating for clean energy across New England.

So some states, including California, Idaho, and Michigan, have implemented programs to compensate individuals and nonprofits who take part in regulatory proceedings by cross-examining the utilities and bringing in experts to testify.

In Connecticut, one of the states where Tully works, it took a natural disaster to usher in change. Hurricane Isaias left some 750,000 people without power in August 2020, some for more than a week. The state’s utility commission, the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority, or PURA, ultimately issued millions of dollars in fines over utilities’ slow response or lack of preparation. The storm, Tully said, got state leaders thinking seriously about how those utilities are governed.

“That was the catalyst that got a lot of legislators talking about the need for change within the world of utility regulation,” he said.

Connecticut had already established an advisory council to help bring the needs of low-income residents before energy regulators. But in the wake of the storm, officials took reforms further. The governor, who appoints the three members to PURA, established an additional advisory board focused on equity and energy justice, which advocates said is helping their efforts to get more people and groups interested in clean energy and environmental justice involved with the complicated and difficult process of energy regulation. The Regulatory Authority has subsequently opened a proceeding focused on equity and stakeholder engagement.

The state legislature, meanwhile, passed laws directing PURA to implement two key changes: stakeholder compensation and performance-based regulation. The state’s stakeholder compensation program covers attorneys’ fees, expert witness fees, and other costs for intervening groups. Performance-based regulation lets the commission tie utilities’ profits to how they perform in certain areas, like keeping rates affordable or cutting emissions. Because investor-owned utilities receive a profit range set by their regulators and are allowed to pass costs like construction and fuel on to their customers, critics argue they don’t have much incentive to keep those costs low or pursue programs like rooftop solar and energy efficiency that might lower emissions but also cut into profits. This approach aims to flip those incentives around, pushing electric companies to change their practices.

It’s not a shift utilities are often fond of, and their powerful lobbying efforts can be a major obstacle. The resistance in Connecticut was so vehement, Tully said, that lawmakers in Maine abandoned a similar bill.

“This is a perennial risk of these kinds of proceedings,” he said. “It represents a threat to the status quo of how utilities have been operating for many, many years.”

Some utilities argue that changing their profit structure in this way could hurt their ability to finance major, necessary energy projects — one of the primary strengths of large utility companies. But that doesn’t seem to be the case in the long run. Although the increased uncertainty while regulators are hashing out the details can make creditors wary, in Hawaiʻi, the performance-based regulation framework actually improved utilities’ credit rating. Some consumer groups, meanwhile, have raised concerns about performance-based regulation because they argue that utilities could easily misrepresent their performance to regulators.

The Connecticut commission is still working on how it will implement performance-based regulation, and the other changes are relatively new as well, so their impact is still “to be determined,” Tully said. But he and his colleagues were encouraged that the advisory councils have pushed PURA to consider equity.

Getting utility commissions to run differently, advocates said, can be a steep uphill battle, especially in the face of strong resistance from utilities. But it can work. Other states have implemented policies like Connecticut’s, and taken other steps, sometimes at the behest of state legislatures and sometimes because commissioners decided to take action.

While a hurricane kickstarted change for Connecticut, it also took a lot of advocacy — both “up and out,” said Jayson Velazquez, one of Tully’s colleagues based in Hartford. The group and its allies lobby “up,” working to get lawmakers and commissioners on board with passing reforms. And they also work “out,” communicating their findings and the issues before the commission to the public and engaging environmental justice groups and community members.

“A lot of the work that we’re doing is bridging that gap between environmental justice groups and our regulators,” Velazquez said. “You kind of have to raise the collective consciousness of the groups before you can really get into effecting change.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The race for clean energy is local on Nov 4, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

It was 2:30 in the morning on November 6, 2014, when flames engulfed the New Orleans home of political consultant Mario Zervigon. Someone had lit his cars on fire, and the flames spread to his house. Zervigon and his family barely made it out of the three-unit building alive. Multiple cats didn’t.

Law enforcement deemed it arson and investigated whether the fire was related to Zerivigon’s campaign work. (The case would ultimately be closed without naming a suspect.) The night before the fire, Zervigon had celebrated the primary election victory of one of his clients for a seat on Louisiana’s Public Service Commission (PSC), a down-ballot position with vast power over the state’s oil, gas, and utility companies.

The candidate, Forest Bradley-Wright, was running as a Republican on a reform platform. He had rejected donations from companies the PSC oversees — a rarity in Louisiana. But the firebombing rattled his campaign. Zervigon took a leave of absence, Bradley-Wright’s fundraising flagged, and another candidate, who had received generous support from the companies in question, eked out a 1.6 percentage point win in the general election.

Bradley-Wright now says he believes the firebombing was an act of “political terrorism” meant “to intimidate or at least cripple my campaign.” He argues the incident is worth revisiting because it shows just how high the stakes can get in the election of regulators charged with making, in some cases, billion-dollar decisions and shaping a state’s energy policies.

“Public utility commissions — especially in the context of climate change — are really important institutions that most people aren’t even aware exist,” said Jared Heern, a Brown University researcher who studies the relationship between the commissions and the industries they regulate.

But fossil fuel companies and electric utilities, their lawyers and consultants, are well aware of their importance.

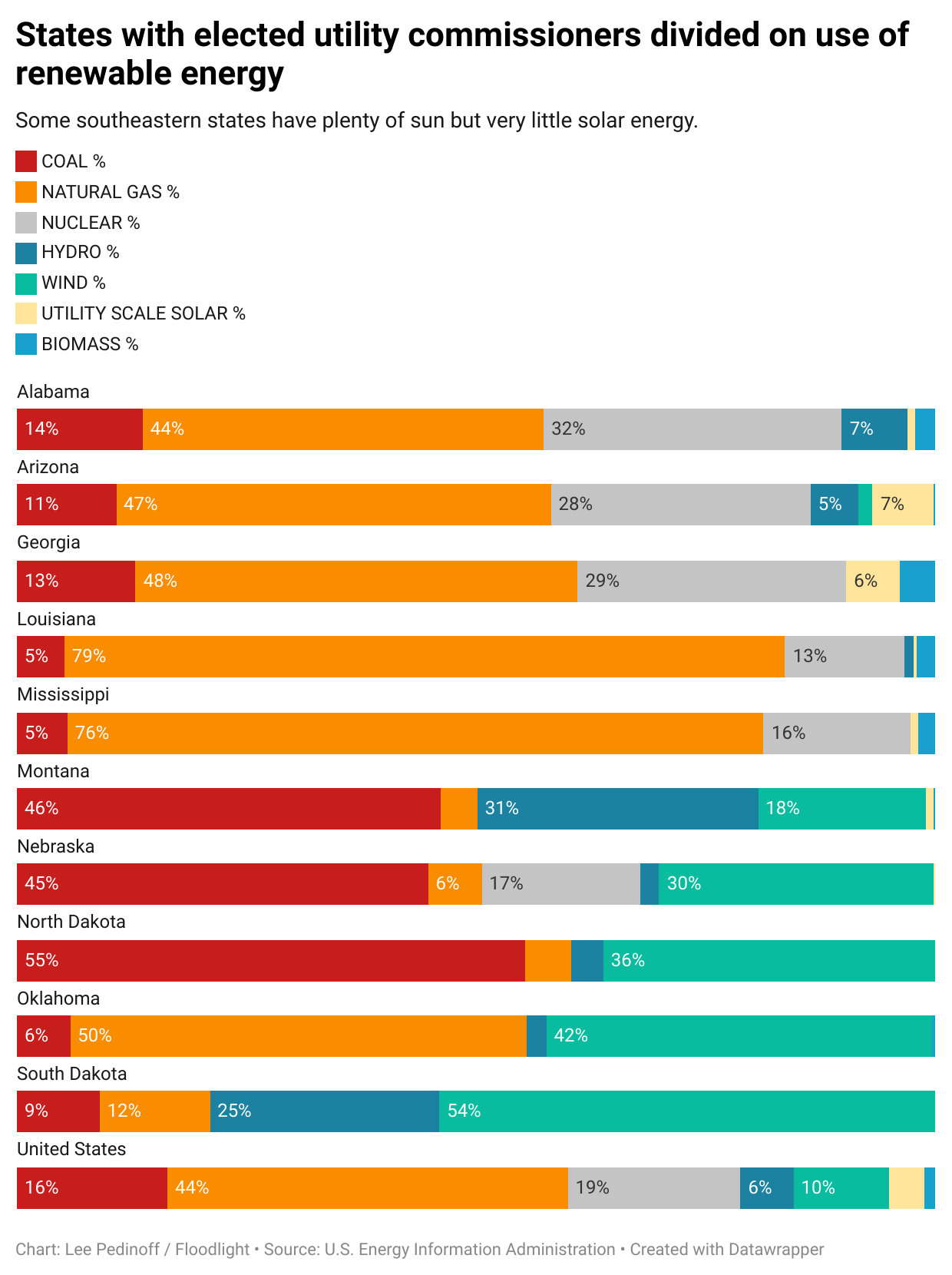

A new Floodlight analysis of campaign finance data in nine of the 10 states that elect their commissioners found that more than a third of their contributions of $250 and up are from fossil fuel and electric utility interests — more than $13.5 million in all.

The analysis covered contributions to the 54 commissioners elected in the 10 years ending on December 31, 2023. On Tuesday, voters will choose among 33 candidates vying for utility commission seats in eight of those states.

The states examined were Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. Nebraska, which elects its commissioners but has no private electric utilities, was excluded. In the remaining 40 states, utility regulators are appointed by governors and/or legislative leaders.

Topping the influence list is Alabama, where commissioners get almost 55 percent of their support from fossil fuel and utility interests. Louisiana is second, with nearly 43 percent. Overall, those interests contribute more than twice as much as the renewables industry does to elect commissioners they believe will be friendly to their interests.

The renewables donations accounted for only $5.1 million, or 13 percent, of the roughly $39 million analyzed.

The findings suggest that the electoral influence of fossil fuel and utility contributors may be interfering with some states’ ability to decarbonize, with consequences for consumers and the environment alike.

Indeed, a number of the states are located in the Sun Belt, making them ideal for solar energy development, yet their commissioners’ decisions have ensured that only a tiny fraction of their power mix comes from the sun. In some cases, commissioners appear openly hostile to the adoption of renewables, far more of which will be needed to limit the catastrophic effects of climate change.

This failure to adapt is a bad deal for homeowners and businesses. Residential energy bills in Alabama, for example, exceed the national average by $32 a month, and bills in Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi have increased faster than the national average over the past five years, according to data from Findenergy.com. This year in Arizona, power bills spiked amid the state’s hottest summer on record. In Oklahoma, commissioners approved so many fracking applications that the state briefly led the country in earthquakes.

“It's kind of ludicrous on its face,” said journalist David Roberts, who hosts an energy policy podcast called Volts, “that commercial entities directly regulated by these people are allowed to give these people money.”

In fact, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi prohibit regulated utilities from making direct campaign contributions to commissioners. But in all of those states, Floodlight’s analysis found, contractors, attorneys, and political action committees closely aligned with the utilities keep the money flowing.

“(When) the people regulating the utility are essentially propped up by the utility itself, it's problematic,” said Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law initiative at Harvard University. “I think everybody can recognize that as a conflict of interest.”

It also turns out that the commissioners who get a large share of their campaign cash from sources linked to fossil fuel firms and utilities tend to stay in office longer than their colleagues.

Nationwide, utility commissioners serve 5.9 years on average. In states where they are elected, these officials became more entrenched, serving 7.4 years — and a whopping 9.2 years in states where fossil fuel and utility interests account for at least 30 percent of their campaign contributions, according to Floodlight’s analysis of data provided by Heern.

Consider Alabama PSC member Jeremy Oden. During his 12 years in office, Oden, a Republican, received about $1.3 million, roughly 80 percent of his campaign funds, from sources with links to fossil fuel companies and utilities.

While Alabama commissioners cannot take money directly from the companies they oversee, our analysis and leaked records revealed that Oden’s top donors were political action committees operated by accountants with long-standing ties to consultants for Alabama Power, the state's largest utility.

Oden did not respond to requests for comment. Tim Whitt, a principal of the campaign committee to elect Oden, provided a written statement. “All of his campaign contributions have been received and reported in accordance with Alabama law,” it stated, adding: “Commissioner Oden has not received any campaign contributions from regulated utilities.”

The cash flowing into Oden’s campaign coffer has come in handy for tight races, like the first round of the Republican primary in May 2022. If he won the primary, Oden, already in office for a decade at the time, would be certain to win the general election in deep red Alabama.

The three Republicans running against him were calling for more renewable energy and cheaper bills. Alabama, a state with strong solar potential, generates less power from solar arrays than even low-potential states such as Maine and Michigan. It saddles utility ratepayers with some of the nation’s highest electric bills.

So what did Oden do? He took to the airwaves, appearing in TV ads dressed in hunting gear and wielding a shotgun. Calling himself “a Christian conservative pro-Trump Republican,” who “would always fight and defend our God-given Second Amendment rights,” the bald, bespectacled commissioner took aim, but not at his opponents.

“With your help, I’ll shoot down Biden’s Green New Deal and keep the left from jacking up our energy prices,” Oden narrated over footage of him downing clay pigeons.

Bolstered by his advertising budget, he won 34 percent of the vote in the four-candidate field, before going on to clinch the primary runoff, and later, the general election.

As a commissioner, Oden has taken aim at clean energy, imposing steep fees on families who install home solar panels, making it a bad investment choice even though those households would be using far less utility-generated power than before. And he voted for a series of rate increases that have led to Alabama having the Deep South’s second highest energy prices.

Oden and his fellow commissioners have also blocked utility-scale solar and battery storage projects, even some requested by Alabama Power. Such moves — raising the cost of electricity while preventing customers from generating their own — benefit the shareholders and top officials of the utilities Oden is charged with regulating.

“The influence of money in (utility commission) elections is very high because in a vacuum of information, whoever has the most money gets their message out the best,” said Joshua Basseches, an assistant professor at Tulane University who studies energy and climate policy. “In theory, the elected commissioners would be less susceptible to regulatory capture, because they would have to face the voters,” but "in practice, what happens is that these are very low-visibility elections.”

Voters, in other words, have little to go on.

Utility commissions are charged with overseeing the complex activities and fielding the demands of the massive energy conglomerates that the state has granted regional monopoly powers. Commissioners vet new projects, monitor utility financials, and evaluate rate hike requests. The companies, meanwhile, are ensured a guaranteed return on investment, which averages about 10 percent nationally.

Though each commission is different, their basic mission is the same: to ensure a safe and reliable grid and affordable energy for consumers. But sometimes the relationship between regulator and regulated gets a little too cozy, a phenomenon economists call “regulatory capture.”

“Investments in political candidates — and particularly for economic regulators like a utility commissioner — there's no better market return,” said Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization. “The amount of benefit that a utility can get, that a fossil fuel interest can get, from a friendly regulator, is better than anything that the stock market can provide.”

Regulatory capture can be costly to consumers. Since 2017, electricity bills in Georgia have increased by about $45 a month, more than double the national average, according to data from FindEnergy.com. Electricity rates, which constitute just a portion of the bill, have kept pace with the national average. Most of the increase is due to surcharges to pay for the $35 billion buildout of a nuclear generating station originally forecast to cost $14 billion.

Back in 2012, when the Nuclear Regulatory Commission gave Georgia Power permission to build two new reactors at Plant Vogtle, the state’s utility commissioners were receiving 70 percent of their campaign support from companies or people that stood to benefit financially, or not, from their decisions, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

Over the next decade, the five commissioners approved $3.2 billion in cost overruns. ”This nuclear expansion does not make sense. It’s way over budget, way behind schedule,” said Jennette Gayer, director of the nonprofit Environment Georgia.

Although Georgia law bars utilities themselves from donating in PSC elections, nearly one-third of those campaign contributions since 2014 have come from fossil fuel and utility-related interests. Among the donors are Georgia Power executives, regulatory attorneys who regularly have business before the commission, and construction companies that specialize in utility work.

Thanks to a series of legal battles, Georgia hasn’t held elections for its PSC since 2020, and sitting commissioners have not had to disclose their campaign contributions since 2021. “The commissioners follow all campaign finance laws,” said PSC spokesman Tom Krause. “This includes disclosure of all donors and donated amounts as required by state and federal law.”

Critics have similarly pointed to Oklahoma as another place where commissioners’ close relationships to the power companies they oversee might be harming residents. Members of the state’s Corporation Commission (commissions can go by various names) have taken in more than $1 million — nearly 35 percent of donations of $250 or more over the last decade — from sources linked to fossil fuel firms and utilities.

In 2022, the commission rapidly approved a plan for ratepayers to shoulder historic increases on their gas bills. The decision followed the 2021 Winter Storm Uri, which depleted the state’s gas reserves, forcing utilities to purchase gas at exorbitant prices. The $3 average cost for 1,000 cubic feet of gas skyrocketed to $1,200 for a brief time, saddling the utilities with $3 billion in extra costs.

The utilities wanted to pass that loss along to their ratepayers. After the Legislature passed a bill allowing utilities to issue bonds to finance the debt, the corporation commissioners gave the utilities exactly what they wanted. “We paid more for natural gas in three days than we do in a year,” said Nick Singer, a leader with VOICE Oklahoma, a civic engagement coalition. “And they just created a debt instrument to put it on the backs of ratepayers for the next 25 years. And they did it in a couple months.”

This spring, Oklahoma’s attorney general filed a pair of lawsuits against gas pipeline firms, alleging they helped bid up prices to historic highs during the storm.

Commissioner Bob Anthony was the only one of the three commissioners to vote against securitization. In a July op-ed in The Oklahoman, he called the commission’s vote “the largest fleecing of the Oklahoma ratepayer in the history of the state.”

Asked why his fellow commissioners voted the other way , Anthony, who is serving his final term, told Floodlight: “Follow the money, that’s the heart of it.”

“Correlation does not necessarily determine causation,” Trey Davis, a spokesman for the commission told Floodlight in an email. “And, while you might want to argue a majority decision is analogous to some form of quid-pro-quo, you do not appear to have provided any substance in support of what is tantamount to a spurious and seemingly subliminal allegation.”

Almost all of the states that elect their commissioners are led by Republicans — only Arizona has a Democratic governor. The Deep South states in particular stand out for their dearth of renewable energy.

The Great Plains states of Oklahoma and the Dakotas generate more than 40 percent of their electricity from wind, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Montana and Nebraska get almost one-fifth and one-third of their power from wind, respectively.

But the situation is markedly different in three Deep South states where commissioners are elected. Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi all derive less than 1 percent of their electricity from solar, despite ample solar potential in those states. (Utility-scale solar is the cheapest form of energy currently available.) That’s less than one-quarter of the national average.

In Mississippi, where PSC members got 12 percent of their campaign cash from fossil fuel interests, commissioners are openly dismissive of calls to improve the state’s 37th-place solar energy ranking. During an August “solar summit,” two commissioners abruptly cut off public discussion and ended the session early after pro-solar representatives stood up to speak.

“What’s the result of all this fossil fuel industry money in commission elections?” said Daniel Tait, research and communications director for the Energy and Policy Institute, a utility watchdog. “Very little renewable energy, and in some cases like Alabama and Mississippi, overt hostility.”

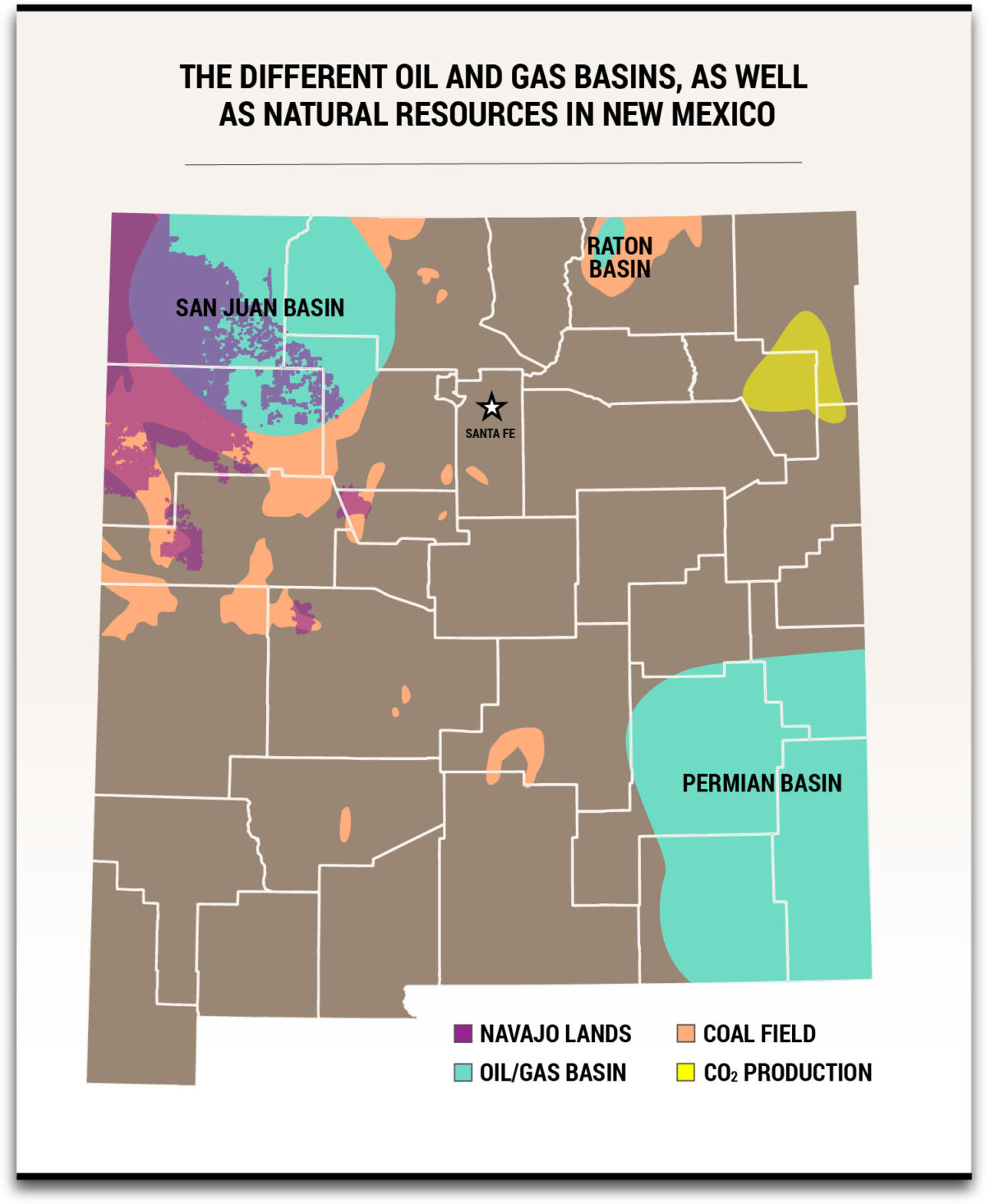

One state recently switched how it picks energy regulators. New Mexico, a Democratically controlled state with a powerful oil and gas industry, transitioned from electing commissioners to appointing them in 2023. The state law governing the transition also required commissioners to have degrees in fields related to energy.

Its fresh slate of appointed commissioners has since approved a rate increase for the state’s primary utility, the Public Service Company of New Mexico — but the amount was only about a quarter of what the utility requested. The commissioners also ordered PNM to return some $115 million in excess profits to its ratepayers. The utility has appealed the clawback to the state Supreme Court.

One energy activist now says she preferred the elected commissioners, because campaign finance data made utility influence easier to trace — and counteract.

“I think that the elected commission was more democratic, even though PNM spent hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to elect the commissioners they wanted,” said Mariel Nanasi, executive director of New Energy Economy, a renewable energy nonprofit. “That backfired for them, and their preferred candidates, at least in more recent times, lost because (the spending) was exposed.”

The patchwork nature of campaign finance record-keeping and disclosure laws in the United States makes it difficult to track all of the industry money flowing into state utility commission elections.

In Mississippi and South Dakota, for example, Floodlight journalists had to manually enter into a database thousands of campaign contributions from records that were handwritten or kept in unsearchable formats.

The money also can also come through supposedly independent groups — including political committees and so-called “dark money” 501(c)(4) nonprofit organizations — making it harder to trace. These groups are allowed to work to support (or oppose) particular candidates but are not legally allowed to coordinate with any candidate’s campaign.

Arizona is the only one of the nine states analyzed that makes tracking independent campaign spending easy. For example, the dominant utility, Arizona Public Service, donated nearly $4.2 million in 2016 to the Arizona Coalition for Reliable Electricity, a political action committee that then spent nearly that exact amount to support the company’s preferred commissioners. (Arizona also provides commission candidates with public financing, which was not included in our analysis.)

Over the past decade, several utilities in Arizona and Alabama have also been caught making large, unreported, and difficult-to-trace dark money contributions to support PSC candidates.

Clearly, utilities and fossil fuel interests are not donating to lawmakers and energy regulators out of the goodness of their hearts, but campaign donations, to be fair, don’t always predict how a legislator or regulator will act. Anthony, the Oklahoma commissioner, received 65 percent of his donations from utilities or fossil fuel-aligned sources. He has often been a lone dissenting voice on the commission against policies that he says put consumers on the hook for the utilities’ mistakes.

Bob Burns, an Arizona Corporation Commission member, got 41 percent of his donations from industry sources. But in 2016, he used his position to crusade for campaign finance transparency from the holding company that owns Arizona Public Service, which stood accused of using millions of dollars of dark money to support its preferred commissioner candidates. (Under pressure from the commission, the company eventually acknowledged its tactics.)

And at least one energy regulator told Floodlight he struggled over whether to take donations from the companies he oversees. “I went through the process of trying to figure out from whom do I accept a donation?” said Gary Hanson, who sits on the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission. His conclusion: “I’m either going to accept donations from everyone or from no one — you either accept from everyone or you don’t accept from anyone.”

He took the money.

Floodlight reporter Kristi E. Swartz contributed to this story. Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Utility regulators take millions from industries they oversee. What could go wrong? on Nov 3, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

In June, U.S. solar manufacturer Qcells became the second company in the world to register its solar panels with EPEAT, a labeling system that sets sustainability standards for electronics makers. By doing so, the company triggered an obscure regulation that requires federal agencies to purchase EPEAT-certified solar panels. If, say, NASA wants to build a solar farm to power a research facility, it must now purchase panels that meet EPEAT’s strict sustainability requirements — including a first-of-its-kind limit on the carbon emissions tied to solar manufacturing.

There’s just one problem: Although EPEAT launched its solar standards in 2019, as of today, there are only six EPEAT-registered solar panels on the global market. And there are currently no EPEAT-registered solar inverters, devices that convert the direct current electricity a solar panel produces to alternating current electricity, which the grid uses. That doesn’t leave a lot of choices for the federal government, or anyone else who wants to purchase sustainably-produced solar equipment.

That’s why, in October, the Department of Energy, or DOE, launched a new prize that offers up to $450,000 to U.S.-based solar panel and inverter manufacturers that achieve EPEAT certification for their products. As a new wave of domestic solar manufacturing kicks into high gear, the DOE hopes the prize will ensure that companies use efficient processes, sustainable materials, fair labor practices, and low-carbon energy.

“The fact of the matter is, not all solar [products] in their production are created equal,” said Patty Dillon, a vice president at the Global Electronics Council, the sustainable technology nonprofit that manages the EPEAT ecolabel.

Solar panels convert the sun’s rays into electricity in a process that emits no greenhouse gases, which makes them essential for fighting climate change. To achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, the International Energy Agency estimates that the world must add 630 gigawatts of new solar power annually by 2030 — up from the 135 gigawatts installed in 2020.

But some solar panels are more climate-friendly than others. Polysilicon, which is used to make the sunlight-harvesting cells inside silicon panels, is made using an energy-intensive process often powered by fossil fuels. The frames that hold solar panels together are made of aluminum, which is typically smelted in China using coal-powered electricity. The manufacturing processes that turn these materials into a solar panel also require energy, which can lead to more emissions. On a global level, the difference between solar panels manufactured using clean energy and those made with fossil fuels could amount to tens of billions of metric tons of carbon pollution by the middle of the 21st century.

To minimize those emissions, along with other environmental challenges like the use of toxic chemicals and the disposal of solar e-waste, companies must take a hard look at their supply chains and, in some cases, engage in difficult clean-up work. The DOE’s new prize, “Promoting Registration of Inverters and Modules with Ecolabel,” or PRIME, encourages companies to do so by going through the EPEAT registration process.

“EPEAT certification enables companies to show how they have been taking the steps to have more environmentally friendly supply chains and manufacturing processes,” Becca Jones-Albertus, who directs the DOE’s solar energy technologies office, told Grist.

Solar companies seeking EPEAT registration must meet a list of criteria that span four broad themes: climate change, sustainable resource use, hazardous chemicals, and responsible supply chains. Depending on how many standards a manufacturer meets, it can receive an EPEAT Bronze, Silver, or Gold designation.

In addition, as of June, solar manufacturers registered with EPEAT are required to meet the industry’s first-ever criteria for embodied carbon, the emissions generated when a product is produced. For each kilowatt of power produced, no more than 630 kilograms of CO2 can be emitted during the production of an EPEAT-registered solar panel. The limit, Dillon says, represents about 25 percent fewer carbon emissions than the global average. Solar panels that fall below the “ultra low carbon” threshold of 400 kilograms of CO2 per kilowatt of power earn a special EPEAT Climate+ designation.

“That basically represents the best in class,” Dillon said.

It’s difficult to make a direct comparison to fossil fuel plants, since most of their emissions come from operations rather than building infrastructure. But other research has found that over their lifespan, solar plants are considerably more climate friendly, emitting roughly 50 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of energy produced compared with about 1,000 grams per kilowatt-hour for coal.

Meeting EPEAT’s requirements isn’t easy, which might explain why there are only two companies — QCells and the Arizona-based First Solar — currently listed on the registry. And only two solar panels manufactured by First Solar have earned the ecolabel’s Climate+ badge. QCells, which manufactures two EPEAT-registered panels at a factory in Dalton, Georgia, spent about two years going through a “very extensive” certification process that involved collecting data across its supply chain and submitting to a third-party audit, corporate communications lead Debra DeShong told Grist.

“It’s not an easy task,” DeShong said. “It requires resources and it requires a will.”

Other companies may now be motivated to try. QCells’ additions to the EPEAT registry in June activated the Federal Acquisition Regulation, which requires the federal government to purchase goods that meet standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, except in limited circumstances where it’s impractical to do so. In the case of solar panels, that means EPEAT-registered products. The DOE’s PRIME Prize, which provides U.S. solar manufacturers $50,000 for starting the registration process and up to $100,000 per product for up to four products that complete it, offers additional incentive. Jones-Albertus told Grist that the prize was designed to “roughly offset the cost of collecting all the data and moving through the registration process.”

Solar companies “told us that they’re interested in EPEAT certification, but they haven’t gotten there yet,” Jones-Albertus said. “We’re hoping to provide incentives so that companies go through the EPEAT registration process sooner.”

Companies peering deep into their supply chains for the first time might discover they have to make some changes to meet EPEAT registration requirements. To slim down the carbon footprint of its panels, a solar manufacturer might have to switch to a low-carbon polysilicon supplier. (QCells, for instance, is purchasing polysilicon from a facility in Washington state that produces the stuff using hydropower.) Or it might decide to swap out virgin aluminum frames manufactured overseas for recycled steel ones built domestically by Origami Solar, a change that can reduce carbon emissions tied to the frame by upwards of 90 percent. To meet EPEAT’s optional recycled content criteria, a manufacturer could decide to start purchasing recycled panel glass from a company like SolarCycle.

Making these sorts of manufacturing supply chain alterations takes time and money beyond what the new DOE prize will provide. But Dillon, of the Global Electronics Council, is optimistic that more companies will start registering their products with EPEAT now that federal purchasers require it.

Erik Petersen, the chief strategy officer at Origami Solar, believes the Biden administration’s push for clean domestic manufacturing, combined with growing consumer interest in supply chain transparency, will spur more U.S. solar companies to ensure their products meet high sustainability standards.

“What’s exciting is all of these forces are coming together at the same time,” Petersen told Grist. “That really gives the industry an incentive to do the right things.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The Department of Energy wants to pay companies to make greener solar panels on Nov 1, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.

Seventeen days after Hurricane Helene devastated western North Carolina, tearing down power lines, destroying water mains, and disabling cell phone towers, the signs of relief were hard to miss.

Trucks formed a caravan along Interstate 40, filled with camouflaged soldiers, large square tanks of water, and essentials from pet food to diapers. In towns, roadside signs — official versions emblazoned with nonprofit relief logos and wooden makeshift ones scrawled with paint — advertised free food and water.

And then there were the generators.

The noisy machines powered the trailers where Asheville residents sought showers, weeks after the city’s water system failed. They fueled the food trucks delivering hot meals to the thousands without working stoves. They filtered water for communities to drink and flush toilets.

Western North Carolina is far from unique. In the wake of disaster, generators are a staple of relief efforts around the globe. But across the region, a New Orleans-based nonprofit is working to displace as many of these fossil fuel burners as it can, swapping in batteries charged with solar panels instead.

It’s the largest response effort the Footprint Project has ever deployed in its short life, and organizers hope the impact will extend far into the future.

“If we can get this sustainable tech in fast, then when the real rebuild happens, there’s a whole new conversation that wouldn’t have happened if we were just doing the same thing that we did every time,” said Will Heegaard, operations director for the organization.

“Responders use what they know works, and our job is to get them stuff that works better than single-use fossil fuels do,” he said. “And then, they can start asking for that. It trickles up to a systems change.”

The rationale for diesel and gas generators is simple: They’re widely available. They’re relatively easy to operate. Assuming fuel is available, they can run 24/7, keeping people warm, fed, and connected to their loved ones even when the electric grid is down. Indubitably, they save lives.

But they’re not without downsides. The burning of fossil fuels emits not just more carbon that exacerbates the climate crisis, but smog and soot-forming air pollutants that can trigger asthma attacks and other respiratory problems.

In Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, generators were so prevalent after the electric grid failed that harmful air pollution in San Juan soared above the safe legal limit. The risk is especially acute for sensitive populations who turn to generators for powering vital equipment like oxygenators.

There are also practical challenges. Generators aren’t cheap, retailing at big box stores for more than $1,000. Once initial fuel supplies run out — as happened in parts of western North Carolina in the immediate aftermath of Helene — it can be difficult and costly to find more. And the machines are noisy, potentially harming health and creating more stress for aid workers and the people they serve.

Heegaard witnessed these challenges firsthand in Guinea in 2016 when he was responding to an Ebola outbreak. As a paramedic, his job was to train locals to collect blood samples and store them in generator-powered refrigerators that would be motorcycled to the city of Conakry for testing. He had a grant to give cash reimbursements to the lab techs for the fuel.

“This is so hard already, and the idea of doing a cash reimbursement in a super poor rural country for gas generators seems really hard,” Heegaard recalled thinking. “I had heard of solar refrigerators. I asked the local logistician in Conakry, ‘Are these things even possible?’”

The next day, the logistician said they were. They could be installed within a month. “It was just a no-brainer,” said Heegaard. “The only reason we hadn’t done it is the grant wasn’t written that way.”

Two years later, the Footprint Project was born of that experience. With just seven full-time staff, the group cycles in workers in the wake of disaster, partnering up with local solar companies, nonprofits, and others, to gather supplies and distribute as many as they can.

They deploy solar-powered charging stations, water filtration systems, and other so-called climate tech to communities who need it most — starting with those without power, water, or a generator at all, and extending to those looking to offset their fossil fuel combustion.

The group has now built nearly 50 such solar-powered microgrids in the region, from Lake Junaluska to Linville Falls, more than it has ever supplied in the wake of disaster. The recipients range from volunteer fire stations to trailer parks to an art collective in West Asheville.

Mike Talyad, a photographer who launched the collective last year to support artists of color, teamed up with the Grassroots Aid Partnership, a national nonprofit, to fill in relief gaps in the wake of Helene. “The whole city was trying to figure it out,” he said.

Solar panels from Footprint that initially powered a water filter have now largely displaced the generators for the team’s food trucks, which last week were providing 1,000 meals a day. “When we did the switchover,” Talyad said, “it was a time when gas was still questionable.”

Last week, the team at Footprint also provided six solar panels, a Tesla battery, and a charging station to displace a noisy generator at a retirement community in South Asheville.

The device was powering a system that sucked water from a pond, filtered it, and rendered it potable. Picking up their jugs of drinking water, a steady flow of residents oohed and aahed as the solar panels were installed, and sighed in relief when the din of the generator abated.

“Most responders are not playing with solar microgrids because they’re better for the environment,” said Heegaard. “They’re playing with it because if they can turn their generator off for 12 hours a day, that means literally half the fuel savings. Some of them are spending tens of thousands of dollars a month on diesel or gas. That is game changing for a response.”

Footprint’s robust relief effort and the variety of its beneficiaries is owed in part to the scale of Helene’s destruction, with more than 1 million in North Carolina alone who initially lost power.

“It’s really hard to put into words what’s happening out there right now,” said Matt Abele, the executive director of the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, who visited in the early days after the storm. “It is just the most heartbreaking thing I’ve ever seen — whole mobile home parks that are just completely gone.”

But the breadth of the response is also owed to Footprint’s approach to aid, which is rooted in connections to grassroots groups, government organizations, and the local solar industry. All have partnered together for the relief effort.

“We’ve been incredibly overwhelmed by the positive response that we’ve seen from the clean energy community,” Abele said, “both from an equipment donation standpoint and a financial resources standpoint.”

Some four hours east of the devastation in western North Carolina, Greentech Renewables Raleigh has been soliciting and storing solar panels and other goods. It’s also raising money for products that are harder to get for free — like PV wire and batteries. Then it trucks the supplies west.

“We’ve got bodies, we’ve got trucks, we’ve got relationships,” said Shasten Jolley, the manager at the company, which warehouses and sells supplies to a variety of installers. “So, we try to utilize all those things to help out.”

The cargo is delivered to Mars Hill, a tiny college town about 20 miles north of Asheville that was virtually untouched by Helene. Through a local regional government organization, Frank Johnson, the owner of a robotics company, volunteered his 110,000-square-foot facility for storage.

Johnson is just one example of how people in the region have leapt to help each other, said Abele, who’s based in Raleigh.

“You can tell when you’re out there,” he said, “that so many people in the community are coping by showing up for their neighbors.”

To be sure, Footprint’s operations aren’t seamless at every turn. For instance, most of the donated solar panels designated for the South Asheville retirement community didn’t work, a fact the installers learned once they’d made the 40-minute drive in the morning and tried to connect them to the system. They returned later that afternoon with functioning units, but then faced the challenge of what to do with the broken ones.

“This is solar aid waste,” Heegaard said. “The last site we did yesterday had the same problem. Now we have to figure out how to recycle them.”

It’s also not uncommon for the microgrids to stop working, Heegaard said, because of understandable operator errors, like running them all night to provide heat.

But above all, the problem for Footprint is scale. A tiny organization among behemoth relief groups, it simply doesn’t have the bandwidth for a larger response. When Milton followed immediately on the heels of Helene, Heegaard’s group made the difficult choice to hunker down in North Carolina.

With climate-fueled weather disasters poised to increase, the organization hopes to entice the biggest, most well-resourced players in disaster relief to start regularly using solar microgrids in their efforts.