As a shark conservation scientist, one of the most common questions people ask me is, “How are shark populations doing?” To answer this question, it’s important to understand two types of fishery surveys: fishery-independent and fishery-dependent. Fishery-dependent population surveys gather data from fishermen’s catches. These data are valuable because there are many more fishermen on the water than marine biologists. However, they are limited because fishermen fish with the intent to catch as much as possible, which means they regularly change their methods to achieve higher yields. This makes sense economically but limits the scientific value of the data.

In contrast, fishery-independent surveys are designed to use the same methods, which are scientifically more rigorous. “They provide an unbiased characterization of many different things, particularly changes in the abundance of fish populations over time,” Dr. Robert Latour, a professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) at William and Mary. “Since the survey is performed the same way during every research cruise, any changes in what you catch are due to something going on with the population, not changes in how we’re fishing.” — David Shiffman, Ph.D.

Pretty simple interview for my KYAQ show. Sharks, a researcher who is in DC shaping context around POLICY while holding onto the reality of why sharks have to be protected.

Sure, Trump and Company are killing, man, killing science for sure. Habitat? No Such Thing under Semen Drip and his Zeldin Wacko!

The Trump administration proposed a new rule Wednesday that would rescind widespread habitat protections for species protected under the Endangered Species Act, a landmark law enacted in 1973 to conserve the country’s imperiled animals and plants.

That would open the door for developments across the country to be approved even if they significantly disrupt critical habitat for species listed under the Endangered Species Act. The proposed rule, posted in the U.S. Federal Register by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, would “rescind the regulatory definition of ‘harm,’” which is defined as any significant habitat modification or degradation that actually kills or injures wildlife.

“There’s just no way to protect animals and plants from extinction without protecting the places they live, yet the Trump administration is opening the floodgates to immeasurable habitat destruction,” said Noah Greenwald, co-director of endangered species at the Center for Biological Diversity. “This administration’s greed and contempt for imperiled wildlife know no bounds, but most Americans know that we destroy the natural world at our own peril. Nobody voted to drive spotted owls, Florida panthers or grizzly bears to extinction.”

If approved, the rule would mean endangered species would only be protected from actions that intentionally lead to the harm of a species.

“It’s just foundational to how we’ve protected endangered species for the last 40-plus years, and they’re just completely upending that,” Greenwald said.

Photo below: David Shiffman, Ph.D.

Trump Administration’s interpretation of ‘harm’ could gut habitat protections for endangered species

By law, the ESA prohibits the “take” of an endangered species, which includes actions “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” Historically, the “harm” part of this mandate encompasses “any activity that can modify a species’ habitat.”

This interpretation of “harm” has long been used by agencies to extend protections for endangered species to the land or ocean area that it relies on. For example, an oil or gas project may not be able to drill or be forced to modify operations in a certain area that provides habitat for an endangered animal, such as a dune sagebrush lizard. In many cases, the “harm” rule has not blocked projects altogether, but rather resulted in different designs that reduce impacts on endangered species.

In 1995, a group of landowners and timber interests in the Pacific Northwest and the Southeast challenged the regulation’s interpretation in a push to log forests where endangered northern spotted owls and red-cockaded woodpeckers lived. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the broad definition of “harm” on the basis of the Chevron Doctrine, a principle that defers to federal agencies’ expertise for carrying out laws. Last year, however, Chevron was overturned, and the Trump administration has seized on that in the new proposed rule.

The new proposal would eliminate this “harm” definition—and the habitat protections that come with it, according to Dave Owen, an environmental law professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

“The shift here would be to say that just habitat modification that is detrimental to a species, even if the detriment is fairly direct, is not encompassed within the word ‘harm,’” Owen said. The majority of habitat protections related to the ESA fall under the “harm” interpretation, according to a 2012 study by Owen. Now, under the proposal, “the word ‘harm’ is essentially going to be read as an inconsequential nullity,” he said.

+_+

A more realistic and radical perspective: Thirteen Years Ago, Paul Watson, of Sea Shepherd fame:

Quoting Watson . . . .

Captain Paul Watson: Fear and Loathing of Sharks in Western Australia

The truth is that hatred of sharks is a manufactured hysteria thanks primarily, although I’m sure without malice, to Steven Spielberg, who resurrected a long-extinct Megalodon shark as a vicious killing machine in Jaws. The notion of such a shark living today is as fictitious as being attacked in modern times by a Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Targeting Great White sharks means targeting an endangered species and is no different than calling for the extermination of tigers, rhinos, and whales. This is the same kind of shallow-thinking, ecologically ignorant mentality that was responsible for the extinction of the Tasmanian tiger.

If the Premier really wishes to reduce shark attacks he should address the human factors that contribute to shark attacks.

There are three primary reasons for increased shark attacks in the sea off the coast of Western Australia.

The most obvious reason is that blood and dead bodies in the water attract sharks and the ships that transport livestock are a primary source for this attraction. Dead animals are irresponsibly tossed overboard. The daily flow of urine and feces contains the smell of blood. Common sense dictates that if you pour blood into the sea, sharks will respond.

Being an economist, the Premier most likely has decided that the demands of agri-business and Muslims wanting live animals so they can slit their throats while pointing the eyes of their sacrifices towards Mecca, is more important than Australian sharks or Australian surfers.

The second reason is that into these same waters where the sharks are attracted there are surfers, and from below, a surfer on a board looks very much like a seal and not just any seal, but a relatively motionless seal, and to a shark that form flashes like a neon sign saying, EAT.

Even so, most shark attacks on surfers are aborted once the shark realizes that the surfer is not a seal. Still it can be bad news for the surfer.

Solution: Instead of spending excessive tax dollars to exterminate sharks, funds can be invested in creating shark deterrent devices for surfboards and for shark-spotting programs like in South Africa where people are hired to watch the surf and to sound an alarm if sharks are in the area. Research should also be carried out on shark behavior and region-specific environmental factors like the effect of discharged effluent from livestock vessels.

The third reason is overfishing, as the sharks in our oceans have their food resources diminished more and more each year. Those who argue that seals should be culled to lower shark populations are in fact encouraging more attacks because fewer seals will mean fewer meals, and thus more hungry and desperate sharks. If you deprive humans of food, they also are inclined to desperation and, as history clearly demonstrates, starving humans have a tendency to attack and eat other humans.

Premier Barnett has unfortunately already demonstrated in other areas that he prefers extremist solutions. When granting authority recently to police to search and seize property without any suspicion or evidence that a crime was committed, a member of the Barnett government voiced support of this policy by comparing it to the ‘effective’ security measures taken by Adolf Hitler. Premier Barnett defended the statement by Liberal Party member Peter Abetz by saying that Abetz had made a valid point.

And now the policy that Premier Barnett wishes to make is to implement a ‘final solution’ to exterminate sharks in the interest of security.

I have surfed, swum and dove for forty some years with sharks including Great Whites and Tigers and I have never met a shark that threatened my security as a human being.

I have, however, met many politicians who have.

Statistics of Note for Statistician Australian Premier Barnett:

The seven most dangerous sports in the United States:

Hang Gliding

Civilian Pilot

Mountain Climbing

Sky Diving

Recreational Boating

Motorcycle Riding

Scuba Diving (Unrelated to shark attacks, for which there have been very few.)

Annual Average Cause of Deaths in the World:

Automobile Accidents: 2,210,000

Lightning Strikes: 10,000

Fatal Accidents caused while Texting: 6,000

Motorcycles: 4,462 (in the USA alone)

Airplanes: 1,200

Falling or Drowning in Bathtubs: 340

Choking on Hot Dogs: 70

Bees and Wasps: 53

Skate Boarding: 50 (in the USA alone)

Jellyfish: 40

Dogs: 30

Ants: 30

Sky Diving: 21 (in the USA alone)

Vending machines: 13

Riding on Lawn Mowers: 5 (in the USA alone)

Sharks: 5

So David and I broached some of the issues around sharks’ decline and status as ecologically important and threatened animals in the web of marine life. Literally over 500 or six hundred species of these amazing creatures have been scientifically identified.

We talked about much out of this 2,000-page report: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) report, Global Status of Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras,

The IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) Shark Specialist Group (SSG) has published a status report on sharks, rays and chimaeras, nearly 20 years after its first report warned that sharks were threatened but underrepresented in conservation. Today we understand more about sharks, rays and chimaeras than ever before, but the scale of their declines threatens to outstrip improvements made in research and policy.

In Oman, shark liver oil is used in traditional eyeliner. In Indonesia, shark and ray skins are packaged as chips. Skates are the seafood counterpoint to buffalo wings at restaurants in the USA, along with mako and thresher sharks. Across Europe, you can sling a luxury stingray skin bag over your shoulder as you sample shark meat sold as European conger, order veau de mer in France, and find ray cheeks purveyed as a delicacy in Belgium. Ray and shark skins are fashioned into shoes, wallets, belts, handbags and purses in Thailand. In Yemen, even the corneas of shark eyes have been reportedly used for human transplant and the cartilage is marketed as a cure to all sorts of human ailments.

These are the extraordinary country-by-country insights detailed in the report, which consolidates the biology, fisheries, trade, conservation efforts, and policy reforms for sharks, rays and chimaeras across 158 countries and jurisdictions.

At more than 2,000 pages long, the report follows one in 2005 that highlighted a rise in the global fin trade and the low conservation profile of sharks, and especially rays and chimaeras.

Since then, the global demand for shark meat has nearly doubled: the value of shark and ray meat is now 1.7 times the value of the global fin trade. Trade has diversified and products such as ray gill plates, liver oil and skins are valued at nearly USD 1 billion annually.

Sarah Fowler of the Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF) led the 2005 report’s publication and contributed to the latest version.

“The conservation and management of sharks is difficult for a variety of reasons, but many governments are breaking down the silos that separate how we deal with sharks and rays as fisheries resources, and as wildlife to conserve.”

“Nearly 20 years after the first report, there have been drastic changes, with sharks and rays now among the most threatened vertebrates on the planet,” explains Alexandra Morata, the IUCN SSC SSG Programme Officer.

The challenges:

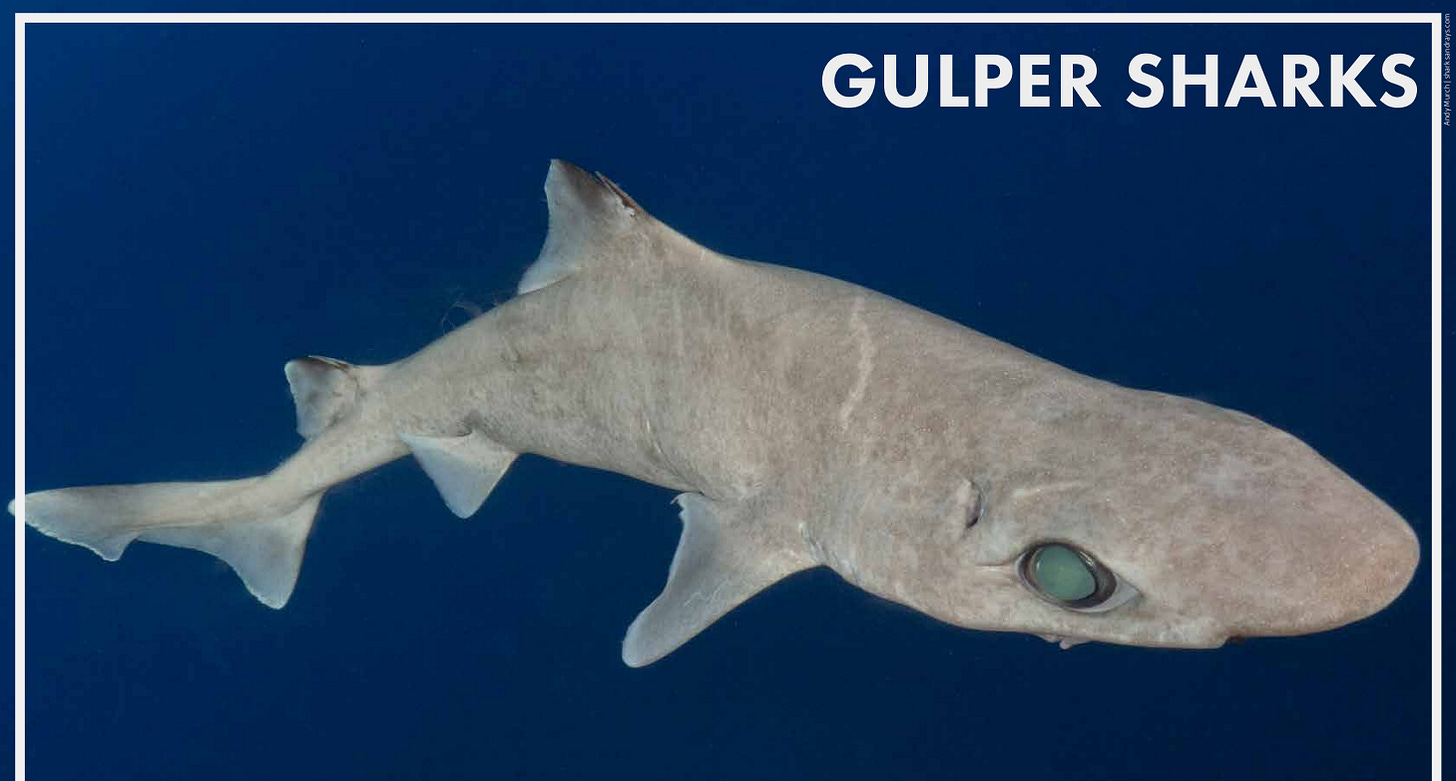

Overfishing is driving most species to extinction. Indonesia, Spain, and India are the world’s largest shark-fishing nations, with Mexico and the USA adding to the top five shark catchers. But only 26% of species globally are targeted: most are caught (and retained) as bycatch. Huge population declines have been seen in the rhino rays (such as wedgefish), whiprays, angel sharks, and gulper sharks.

But two decades of research and major policy changes also mean that the solutions are now outlined country by country and can guide governments to implement conservation action and make fisheries sustainable.

“This report is a call to action so we can work together and make each of the country recommendations a reality, especially those relating to responsible fisheries management. It is the only way these species will survive and continue to thrive in aquatic ecosystems,” says Dr Rima Jabado, the IUCN SSC deputy chair and SSG chair who led the 2024 report.

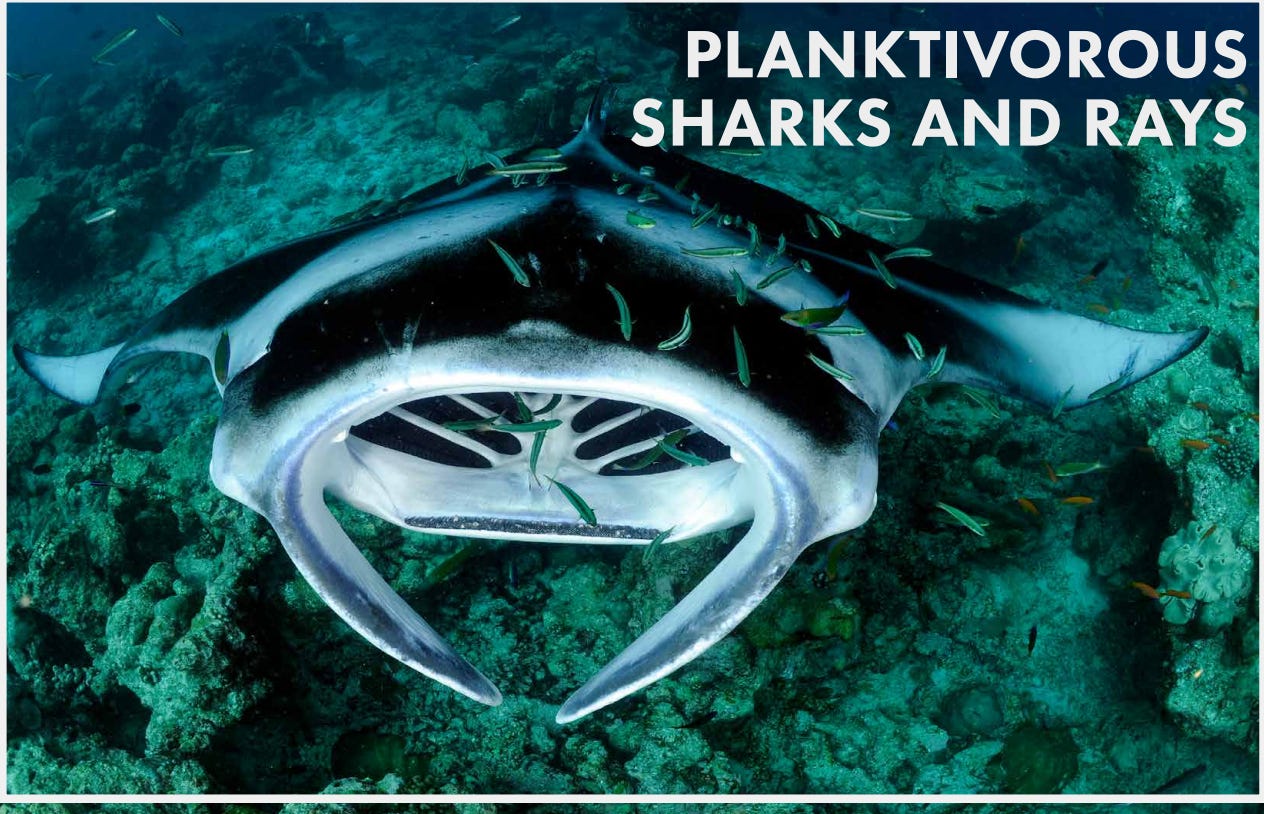

We need sharks, rays and chimaeras.

We are only beginning to decipher the role they play in delivering life-supporting resources and services. Some species cycle nutrients around the ocean; others help us fight climate change by acting as carbon sinks or maintaining carbon sequestering ecosystems like mangroves. They underpin food security in vulnerable coastal communities. In some developing nations, fishers have reported that more than 80% of their income depends on shark and ray fisheries.

“The report is also a reflection of the tremendous dedication of scientists, researchers and conservationists who are working as a community to contribute to conservation and make a lasting change,” Dr Jabado adds.

Access to remote areas, especially across Africa, has increased scientific understanding of the scale of exploitation. Knowledge has improved significantly in Asia, Africa, Central America, the Caribbean, and the Indian Ocean. There are also hopeful instances of sustainable fisheries in Canada, the USA, and Australia.

There have been incredible strides in research and policy, but this hard work will only save species from extinction if the report’s recommendations are implemented nationally.

“The message is clear,” says Dr Jabado. “With the precarious state of many of these species, we can’t afford to wait.”

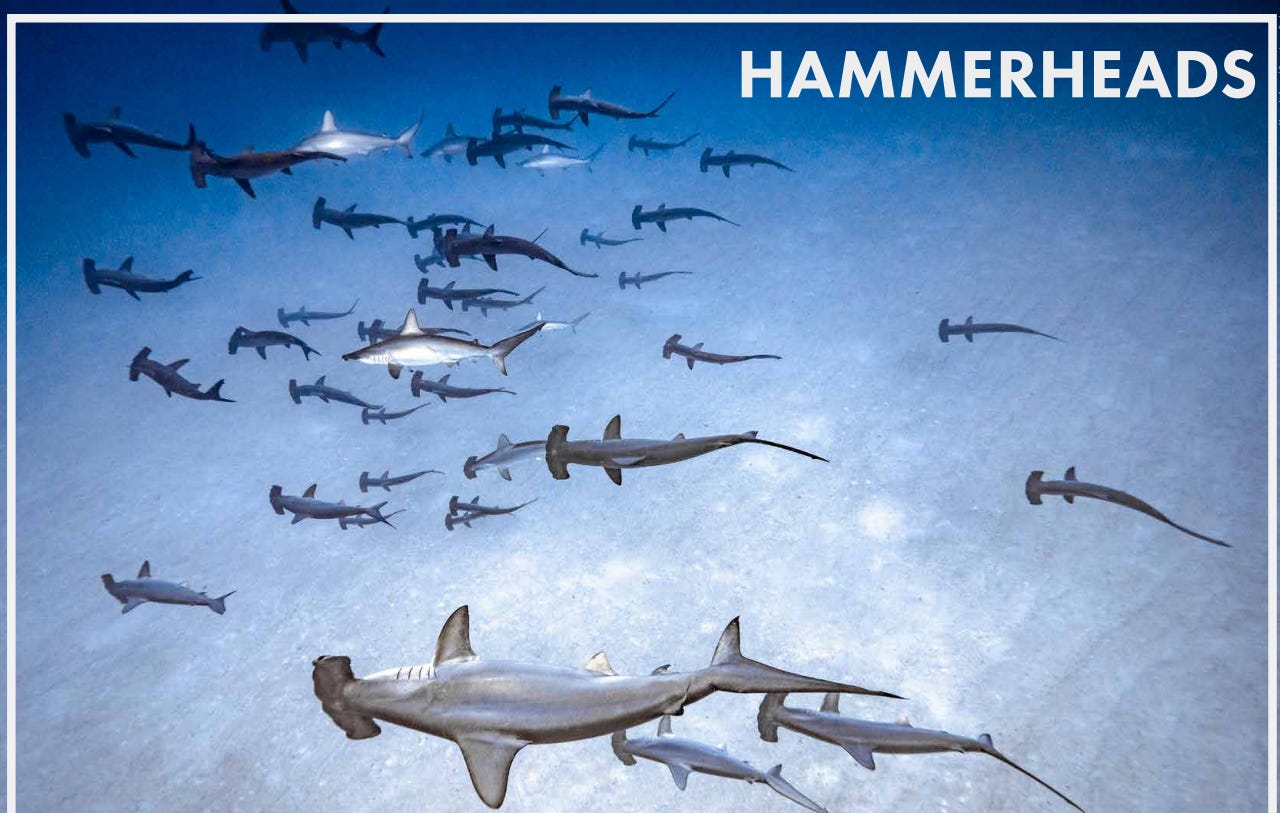

Amazing that I have been with hammerheads in various waters, but many smaller ones in the hundreds off Baja . . .

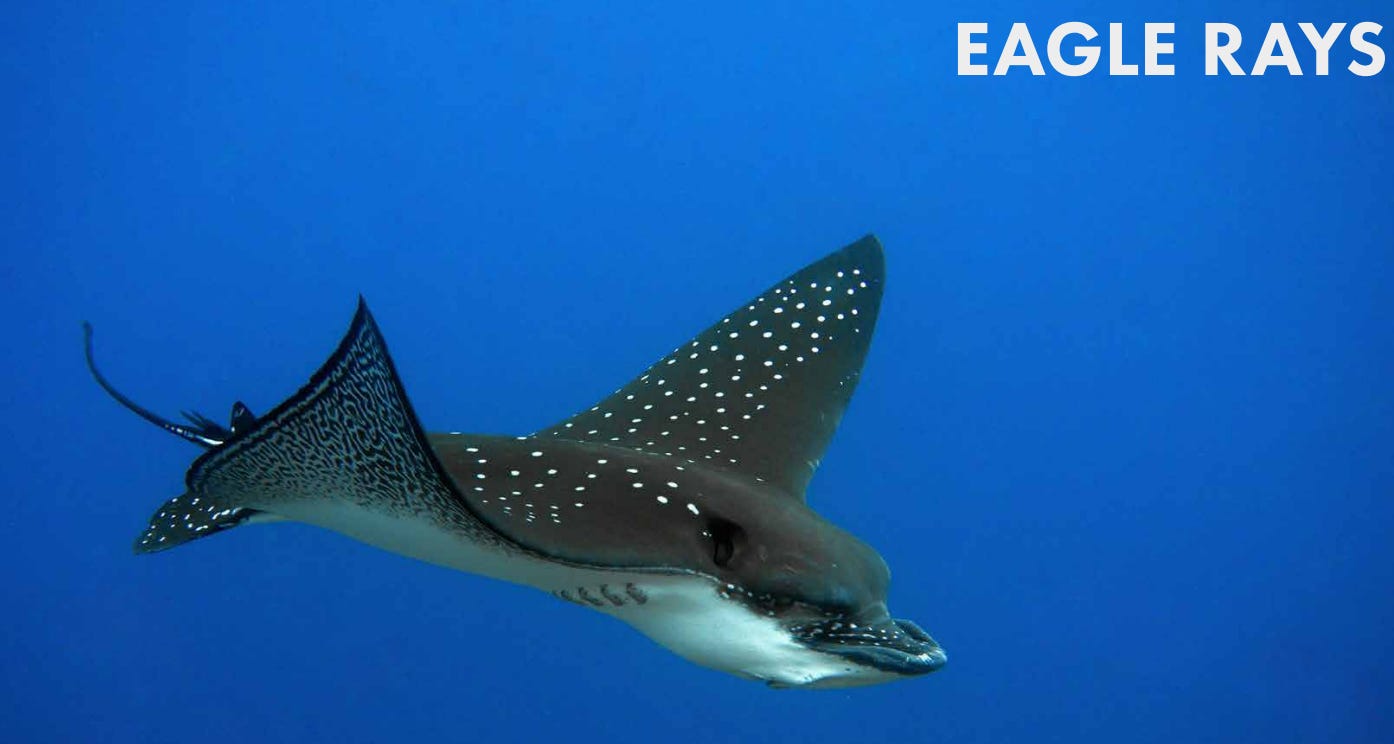

Ran into these too in the Caribbean and elsewhere:

The powerful blue sharks, man, sleek, amazing: In California, where I was born!

Open wide, brother:

A whale of a shark:

Exotica:

The order Rhinopristiformes, also known as rhino rays or sharklike rays, is the most threatened order of marine fish (Kyne et al., 2020; Dulvy et al., 2021). It comprises five families: giant guitarfish (Glaucostegidae), sawfish (Pristidae), wedgefish (Rhinidae), guitarfish (Rhinobatidae), and banjo rays (Trygonorrhinidae; Last et al., 2016; IUCN, 2024). These 68 species of medium to large-sized, benthic rays have a similar posterior morphology to sharks and are distributed in temperate to tropical waters on the insular and continental shelves (usually <250 m depth) throughout the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic oceans (Last et al., 2016; IUCN, 2024).

Information available suggests that rhino rays are strongly associated with soft-bottom habitats such as sand, mud or gravel, and some species are often observed in areas adjacent to coral reefs (White et al., 2013). The distribution of rhino rays is highly variable, from broadly distributed species (e.g., Bottlenose Wedgefish [Rhynchobatus australiae] and Giant Guitarfish [Glaucostegus typus]) to those with very restricted and/ or fragmented spatial distributions, such as Clown Wedgefish (Rhynchobatus cooki) known only from Lingga and Singkep Islands in Indonesia (Kyne et al., 2019; McDavitt & Kyne, 2020), and False Shark Ray (Rhynchorhina mauritaniensis) from a single location in the Eastern Central Atlantic (Iwik in the Banc d’Arguin in Mauritania; Séret & Naylor, 2016).

Like most other shark and ray species, rhino rays have relatively ‘slow’ life-histories with slow growth, late age at maturity, and low fecundity. Life-history data are not available for most species. Rhino rays are viviparous, with litter sizes generally range from one up to 20 pups, though most species typically have less than ten pups per litter (Last et al., 2016). The relatively low productivity in many of these species limits population growth rates and the resilience of these species to exploitation along with their ability to recover once depleted (D’Alberto et al., 2024).

Freshwater skates and rays, too:

Freshwater or euryhaline sharks and rays are usually a forgotten component of shark, ray, and chimera biodiversity, mainly because the vast majority of these species are associated with marine ecosystems. Freshwater rays are cartilaginous fish species that have adapted and developed the ability to live and complete their entire life cycles in freshwater environments (stenohaline), such as rivers, streams, and lakes (Grant et al., 2022).

Origin, systematics, and taxonomy.

Among all living sharks and rays, the Neotropical freshwater stingrays (subfamily Potamotrygoninae) form the only lineage that is exclusively obligate to freshwater environments (Thorson et al., 1978; Rosa, 1985; Lovejoy, 1996; de Carvalho et al., 2016; Fontenelle et al., 2021a). The origin of the subfamily Potamotrygoninae has been hypothesized to have been associated with marine incursion events from the Caribbean into the northeast portion of South America (Thorson et al., 1978; Lovejoy et al., 1998, 2006; Bloom & Lovejoy, 2017; Kirchhoff et al., 2017; Fontenelle et al., 2021b). However, the age of this freshwater lineage is still a topic of debate: while most studies using molecular data associate the origin of the potamotrygonins with the Pebas Wetlands System during the Oligocene-Miocene (Lovejoy et al., 1998; Albert et al., 2021; Fontenelle et al., 2021b), some authors estimate an earlier, Eocene origin (de Carvalho et al., 2004; Adnet et al., 2014).

Watson got criticized by the Fox network because he said worms, trees and bees are more important than people. They got really outraged when he replied with the simple fact that worms, trees and bees can live on this planet without us but we could not live without them.

“People will say you don’t care about people and I guess that’s true but in a way what we do to protect the ocean is protecting the people. We need them, they don’t need us. For example, phytoplankton. We’ve had a 40 percent decrease since 1950. If phytoplankton goes extinct, we go extinct. It provides 70 percent of the oxygen in the air. So people need to become aware of the interdependence of species and how important they are for our survival.”

Listen to David and me talk sharks. He’s serious about this scientific field and he is passionate, and I call him Dave the Shark Science Guy, after Jim Nye that Science Guy!

Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator by David Shiffman

[Dr. David Shiffmanis a Washington, DC-based marine conservation scientist who focuses on the ecology of endangered species and how to protect them. He received his Ph.D. in environmental science and policy from the University of Miami, and is an alum of the Liber Ero Postdoctoral Fellowship in Conservation Leadership. He is the author of “Why Sharks Matter,” and invites you to follow him on Bluesky, where he’s always happy to answer any questions anyone has about sharks, marine biology, or ocean conservation.]

*****

20 years ago: Peter Benchley, author of Jaws.

Quoting him:

Please, in the name of nature, do not mount a mindless assault on an endangered animal for making an innocent – however tragic – mistake.

I’ve just this minute learned about Monday’s ghastly, fatal attack by a great white shark. While I cannot pretend to comprehend the grief felt by Ken Crew’s friends and family, and would not conceive of diminishing the horror of the attack, I plead with the people of Australia – who live with, understand and, in general, respect sharks more than any other nation on earth – to refrain from slaughtering this magnificent ocean predator in the hope of achieving some catharsis, some fleeting satisfaction, from wreaking vengeance on one of nature’s most exquisite creations.

Though I was not there, though I did not witness the hideous moment, I can say absolutely that the shark was not acting with malice toward the man; not with intent to do bodily harm. It was doing what sharks do: assaulting perceived prey.

Australia has had a run of extremely bad luck recently: three human beings have been killed by great white sharks. But it is important for us to realise that these are freak occurrences that by no means signal a sudden onslaught by sharks on swimmers and surfers.

The oft-quoted statistics remain true: shark attacks are very, very rare, and fatal attacks even rarer. A human being is still more likely to die of a bee sting, snake bite or, Lord knows, automobile accident than by shark attack.

We do not execute the perpretrators of death by car. We should not butcher an animal for an inadvertent homicide.

It’s also important that we understand that the shark is not invading our territory, threatening our homes or livelihoods; we humans are the trespassers. And if we choose to swim in the sea, to enter the realm of these wonderful animals – animals that have survived, virtually unchanged, for millions of years, animals that serve a critical function in the oceanic food chain – we are taking a chance.

If we choose to walk into a forest where a tiger lives, we are taking a chance. If we swim in a river where crocodiles live, we are taking a chance. If we visit the desert or climb a mountain or enter a swamp where snakes have managed to survive, we are taking a chance.

No person of sound mind would annihilate all tigers or snakes or crocodiles; we should resist the temptation to mark sharks for destruction.

This was not a rogue shark, tantalised by the taste of human flesh and bound now to kill and kill again. Such creatures do not exist, despite what you might have derived from Jaws.

When I wrote the book and film a quarter of a century ago, knowledge of sharks was in its infancy. We believed that sharks actually attacked boats; we believed that they actively sought out human prey. We believed that their numbers were infinite and the threat they posed incalculable.

Over the years, we have come to know otherwise. Over those same years, unfortunately, the demand worldwide for shark products has soared, and improved technology has given man the tools to slaughter sharks wholesale to meet that demand.

Around the world every year, approximately a dozen people are killed by sharks, while 100m sharks are killed by man. We are already perilously close to killing off the top of the oceanic food chain – with catastrophic consequences that we can’t begin to imagine. Let us not, in the heat of anger, reduce the already devastated population of great white sharks by one more member.

Let us mourn the man and forgive the animal, for, in truth, it knew not what it did.

Great White, Deep Trouble, a documentary about Peter Benchley and his work

The post Sharks and Rays and Skates and Chimaeras: Spielberg/Benchley Messed it up big time back then for Great WHITES — Now? first appeared on Dissident Voice.

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Paul Haeder.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.

2025 is ending with more smashed climate records, as large parts of the Northern Hemisphere recorded their highest December temperatures on record:

ABSOLUTE MADNESS

Night Minimums up to 64F in Illinois

NIGHT TEMPERATURES TYPICAL OF JULYHundreds oF records pulverized allover Central States with up to 8F margins

and the weekend will be hotter,in some areas much hotter.It s the most extreme event in US climatic history. pic.twitter.com/nG6Y60X9fk

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) December 26, 2025

Record heat

As the Guardian reported, 25 December saw the US hit its warmest Christmas Day on record — what you might call a ‘red Christmas’.

Meteorologists have attributed the extreme weather to a ‘heat dome’ in which high pressure has trapped warm air near the surface.

Record temperatures from Christmas day included Oklahoma City, which hit 25°C (77°F). Additional records have fallen since then:

EXTRAORDINARY SUMMER NIGHT

Hundreds of records warm night in over a dozen States again

MINIMUMS up to

71F in Texas

70 Louisiana

66 Arkansas,Kentucky and Georgia

65 Tennessee

64 Oklahoma and MIssissippi

63 Missouri

62 AlabamaMillions with AC for Xmas holidays: A total insanity https://t.co/NvPK0CcwN5

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) December 26, 2025

Temperatures have also hit record highs in Iceland:

At about 11 a.m. on Christmas Eve, Seyðisfjörður in eastern Iceland recorded 19.8°C, the highest December temperature ever measured in Iceland, according to RUV. pic.twitter.com/HNkIYRNwum

— Joakim

(@joakial_) December 25, 2025

This temperature anomaly over the Northern Hemisphere, especially the USA and Iceland is pretty nuts. Heat records for Christmas and December are being smashed all over pic.twitter.com/5UihD6xJNo

— Stefan Burns (@StefanBurnsGeo) December 26, 2025

While the Northern Hemisphere experiences Winter, the Southern experiences summer. And as people have highlighted, the upside down temperatures in the North aren’t always corresponding with a similar flip below the equator:

HISTORIC HEAT IN AFRICA

Records smashed continously,alloverDecember records today:38.8 Magaria and Goure in NIGER

Every single country has been smashing records since Day #1 and will get worse next days.It's the most extreme event ever recorded anywhere in the tropics. https://t.co/hMRLcj52qc

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) December 26, 2025

Australia, however, has experienced record-breaking low temperatures for December:

If many Americans feel a touch of summer in winter, some Australians are feeling a touch of winter in summer.

Very cold conditions in the SEOnly 1.8C in Flinders Island,Tasmania – a cold record for December and 5C below winter average!

5.6C Low Head also record pic.twitter.com/0XEG6IxzyI

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) December 26, 2025

Climate change

‘Global warming’ is the phenomenon of average global temperatures increasing year on year. Berkley visualised this in the following graph:

‘Climate change’ is what happens to climate systems as a result of rising temperatures and other factors. Essentially, climate change results in more chaotic climate and weather patterns, which is why we’re more likely to see both record heat and record cold. It’s also why extreme weather events are more common:

Perpetual reminder: extreme rainfall events increase due to #globalheating. Weather station data show what has been predicted for over 30 years by climate scientists. These extremes are now far outside the historical climate.

Study: https://t.co/B4Ac8DBpyX https://t.co/Na0KDgvny8— Prof. Stefan Rahmstorf

(@rahmstorf) December 26, 2025

The following graph from Statista demonstrates that the frequency of floods, storms, and extreme temperatures have all spiked in the past few decades in Europe:

The following from Visual Capitalist shows something similar for the US:

While we can’t conclusively link individual weather events to climate change, we can state that the phenomenon is causing the increased frequency of them. While we’ve made significant progress on our ability to de-carbonise, however, the US has recently ‘gone into reverse’:

HUMANITY IS RAPIDLY EVOLVING into a solar-powered civilization—with China leading the way and the United States making a u-turn to go backwards, a new book says.

Fully 95% of new generating capacity for planet Earth last year came from next-generation clean sources, says 'Here… pic.twitter.com/AXKiI3IyOU

— Nury Vittachi (@NuryVittachi) December 26, 2025

Featured image via Tropical Tidbits

By Willem Moore

This post was originally published on Canary.

“Scarface,” a young Gray wolf in Hayden Valley, Yellowstone National Park. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Last week, Lauren Boebert’s cynically-named “Pet and Livestock Protection Act” passed the House of Representatives on a narrow, largely party-line vote. Five Democrats broke ranks and voted for it (Gleusenkamp Perez – WA, Cuellar – TX, Gonzalez – TX, Costa – CA, and Gray – CA), while four Republicans broke ranks and voted against it (Fitzpatrick – PA, Buchanan – FL, Van Drew – NJ, and Fine – FL). It is an attack on wolves, but just as importantly an attack on the Endangered Species Act itself. More to the point, the bill is an embodiment of Boebert herself – extreme, dishonest, and deeply anti-wildlife.

The bill forces the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to reissue its 2020 nationwide wolf delisting, a decision a federal court immediately overturned for the agency’s failure to base their decision on science. That outcome would dismantle all federal protections for wolves by turning wolf management over to state governments. The de-listing of wolves in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho (also forced by a congressional rider) serves as a sobering preview of how removal of federal protections unfolds: All three states immediately instituted trophy hunting and trapping seasons under regulations so flimsy that wolves are targeted for night hunting with enhanced vision goggles, wolves are being run over with snowmobiles with impunity in Wyoming and Idaho, and in 86% of Wyoming, wolf killing is completely unregulated – no limits on hunting season, bag limits, or methods. Even a hunting license isn’t required.

The Boebert wolf delisting bill also blocks judicial review, an extreme and un-American step in seizing power from the public which prevents any appeal to the courts. So regardless of how badly the ecological trainwreck of wolf delisting becomes – even including extirpation of the species throughout the lower 48 states – there would be no avenue for legal accountability. Which is precisely Boebert’s goal.

Boebert first introduced wolf delisting legislation in February of 2023, titled the “Trust the Science Act.” The name was ironic since wolves protected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act could only be delisted if the science showed that their populations were fully recovered, and the threats that risked extinction were removed. Neither had happened. So instead of trusting the science, Boebert proposed legislation that would force the delisting of wolves, circumventing the science and removing federal protections by political fiat, and blocking any legal accountability through the courts.

Exactly one year previously, conservation groups including Western Watersheds Project had successfully won a lawsuit challenging the first Trump administration’s nationwide delisting of wolves. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had gone through the rulemaking process, prescribed under the Endangered Species Act, and issued a determination that wolves were fully recovered and no longer needed federal protection. But agency decisions are subject to judicial review, and conservation groups from across the country challenged this delisting as a political hatchet-job rather than a science-based conclusion. The court ultimately agreed and struck down the nationwide delisting for the agency disregarding the best available science and failing to undertake an adequate threats assessment.

Notwithstanding the fact that the judicial system had just resolved the question, Boebert ginned up a bill that would undermine the science, bypass the courts, and named it the Trust the Science Act.

Through ridiculous antics of all kinds, Lauren Boebert became so unpopular that she was basically run out of western Colorado. Her gun-themed restaurant in Rifle, Colorado – Shooter’s Grill, where waitresses openly carried firearms – was forced to close its doors in July 2022 when the landlord decided not to renew her lease. Her campaign office, leased from the same landlord, also was terminated. Boebert famously has a track record of voting against immigration included targeting ‘sanctuary cities’ for federal defunding, opposing a path to citizenship for “Dreamers,” undocumented adults brought to the United States as children. So it looked like karma when Boebert’s former restaurant location was leased out to Tapatios Family Mexican Restaurant.

Boebert’s extreme brand of politics was branded “angertainment” by a political opponent named Adam Frisch, a relative unknown who nearly won a bid to unseat Boebert in the 2022 congressional race. With 99% of the district reporting, Frisch led the race. After a recount, Boebert survived by a mere 546 votes. Rather than face Frisch (and western Colorado voters) again, Boebert decided to leave and run for Congress on Colorado’s eastern Plains, after incumbent Rep. Ken Buck announced that he would be retiring (citing disgust with the January 6th insurrection at the Capitol and Trump’s lies about the 2020 election results).

On January 6th, 2021, Boebert herself made a cryptic post stating that “Today is 1776,” at 5:30 in the morning (presumably Mountain Time). Four and a half hours later, at noon Eastern Time according to a timeline of the January 6th insurrection, President Trump made his speech claiming that the election result was fraudulent and called on Vice President Mike Pence not to certify it; the first rioters arrived at the Capitol building at 1 pm. After Donald Trump lost his re-election bid in November 2020, Lauren Boebert had been one of a handful of congressional lawmakers invited to meetings to plan the events of January 6th. At 1:55 pm, Boebert rose to make her first speech on the floor of the House. In the midst of her yelling rant, she blurted out, “Madame Speaker, I have constituents outside this building right now. I promised my voters to be their voice!” Years later, during the congressional investigation of the January 6th riot, a Proud Boys document came to light, laying out an eight-page blueprint for planning the insurrection. It was titled, “1776 Returns.”

But, if Lauren Boebert belongs to the lunatic fringe of the political spectrum, the “paramilitary wing of the GOP” as one newspaper editor put it, or was even a co-conspirator in the January 6th insurrection, why should that be relevant to her efforts to strip federal protections from the gray wolf? The answer is simple: Legislating to de-list a species under the Endangered Species Act is an extreme and dangerous precedent, requiring an extreme and environmentally unhinged proponent. Boebert’s unhinged approach disqualifies her as a representative to be taken seriously.

When Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 (92 to 0 in the Senate, 355 to 4 in the House), the central point was to make listing and de-listing decisions solely on the basis of science— to get rid of the political interference that had accelerated extinctions for the first two centuries of American history. Polling has shown overwhelming public support for the law ever since, despite the efforts of anti-conservation lobbyists to convince us otherwise. Harriet Hageman (R-WY), the sponsor of a similar bill to force the de-listing of grizzly bears to strip them of ESA protections, also supports selling off public lands and primaried incumbent Liz Cheney on the basis of her role in spotlighting efforts to overthrow the presidential election during January 6th Commission hearings. The credibility of the proponents of these attacks—on January 6th and on the ESA—undermines the credibility of their legislation.

Fast forward to April 2024, when Boebert was able to get her “Trust the Science Act” bill to force wolf delisting passed by a four-vote margin in the House. Yadira Caraveo (D-CO) was one of four Democrats who voted in favor, and she was voted out of office that year by a Colorado electorate that had voted in favor of a ballot measure to compel wolf reintroduction in the state just four years previously. The bill was then referred to the Senate, but died without ever receiving a floor vote.

Meanwhile, conservation groups were in court to challenge the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s denial of two petitions (by Western Watersheds Project, seeking a West-wide listing and Center for Biological Diversity, seeking an emergency Northern Rockies listing) to re-list the federally-unprotected wolves in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and parts of eastern Oregon and Washington. In July of 2025, that lawsuit was successful. The judge ruled that a West-wide Distinct Population Segment was the most appropriate population unit qualifying for protection, and that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to deny listing it was contrary to the best available science. The judge took particular note of the scientific shortcomings of unreliable population models in Idaho and Montana, and his ruling called into question the agency’s arbitrary decision to ignore the need to recover wolves in historic habitats they had not yet repopulated. So not only is wolf listing still warranted in the states with small and struggling wolf populations, it is even warranted in the states where wolf populations are largest. Because threats to the species are part of the calculus.

Now, in 2025, Boebert has rebranded an identical wolf-delisting bill as the “Pet and Livestock Protection Act” ( another misnomer because it does not contain any provisions to protect either livestock or pets). Once again, having passed the House, it heads to the Senate, this time during an election year roiled by a White House embroiled in controversy, putting seemingly safe Republican districts back in play. Senate Democrats have historically stood strong against attacks on the Endangered Species Act involving a variety of species, including wolves. After all, the whole point of the Endangered Species Act is to get political meddling out of the equation and put science in the driver’s seat. But in these anything-goes times, nothing can be taken for granted. Watch for a major push by conservation groups to block Boebert’s wolf-extinction agenda, and see which special interests support the bill, or stay silent on the sidelines.

The post Lauren Boebert’s All-Out Anti-Wolf Assault on the ESA appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Image by Lukáš Lehotský.

The Trump family is now directly investing in atomic energy. Its money-losing Truth Social company has become a part owner of a major fusion nuclear power project.

Among much more, the investments mean the Trump family stands to profit directly from White House attacks on wind, solar and other cheap, clean renewable energies which for decades have been driving fusion, fission and fossil fuels toward economic oblivion.

“A Trump-sponsored business is once again betting on an industry that the president has championed, further entwining his personal fortunes in sectors that his administration is both supporting and overseeing,” reported an article on the front page of the business section of the New York Times last week. “This one is in the nuclear power sector. TAE Technologies, which is developing fusion energy, said on Thursday that it planned to merge with Trump Media & Technology Group. President Trump is the largest shareholder of the money-losing social media and crypto investment firm that bears his name, and he will remain a major investor in the combined company.”

The headline of the piece: “Trump’s Push Into Nuclear Is Raising Questions.”

The primary asks have to do with economic conflicts of interest, and public safety.

“The deal, should it be completed,” the article continued, “would put Mr. Trump in competition with other energy companies over which his administration holds financial and regulatory sway. Already, the president has sought to gut safety oversight of nuclear power plants and lower thresholds for human radiation exposure.”

CNN reported: “Nuclear fusion companies are regulated by the federal government and will likely need Uncle Sam’s deep research and even deeper pockets to become commercially viable. The merger needs to be approved by federal regulators—some of whom were nominated by Trump.”

CNN quoted Richard Painter, chief White House ethics lawyer under President George W. Bush, as saying: “There is a clear conflict of interest here. Every other president since the Civil War has divested from business interests that would conflict with official duties. President Trump has done the opposite.” Painter is now a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School.

“Having the president and his family have a large stake in a particular energy source is very problematic,” said Peter A. Bradford, who previously served on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the agency meant to oversee the nuclear industry in the United States, in the Times article.

“The Trump administration has sought to accelerate nuclear power technology—including fusion, which remains unproven,” Bradford said. “That support has come in the form of federal loans and grants, as well as executive orders directing the NRC to review and approve applications more quickly.”

Still, the White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, said in a statement that “neither the president nor his family have ever engaged, or will ever engage, in conflicts of interest.” And the Times piece continued, “a spokeswoman for Trump Media” said the company was “scrupulously following all applicable rules and regulations, and any hypothetical speculation about ethics violations is wholly unsupported by the facts.”

It went on that “Trump’s stake in Trump Media, recently valued at $1.6 billion, is held in a trust managed by Donald Trump Jr., his eldest son. Trump Media is the parent company of Truth Social, the struggling social-media platform. The merger would set Trump Media in a new strategic direction, while giving TAE a stock market listing as it continues to develop its nuclear fusion technology.”

The Guardian quoted the CEO of Trump Media, Devin Nunes, the arch-conservative former member of the House of Representatives from California and close to Trump, who is currently chair of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board, saying Trump Media has “built un-cancellable infrastructure to secure free expression online for Americans. And now we’re taking a big step forward toward a revolutionary technology that will cement America’s global energy dominance for generations.” Nunes is the would be co-CEO of the merged company.

A current member of the US House, Don Beyer, a Democrat from Virginia, said in a statement quoted in Politico that the deal raises “significant concerns” about conflicts of interest and avenues for potential corruption. “The President has consistently used both government powers and taxpayer money to benefit his own financial interests and those of his family and political allies. This merger will necessitate congressional oversight to ensure that the U.S. government and public funds are properly directed towards fusion research and development in ways that benefit the American people, as opposed to the Trump family and their corporate holdings.”

By federal law (the Price-Anderson Act of 1957) the US commercial atomic power industry has been shielded from liability in major accidents it might cause. The “Nuclear Clause” in every US homeowner’s insurance policy explicitly denies coverage for losses or damages caused, directly or indirectly, caused by a nuclear reactor accident.

As his company fuses with the atomic industry, Trump acquires a direct financial interest in gutting atomic oversight—which he has already been busy doing. In June Trump fired NRC Chairman Christopher T. Hanson. No other president has ever fired an NRC Commissioner.

. Earlier, more than 100 NRC staff were purged by Elon Musk’s DOGE operation. There has been a stream of Trump executive orders calling for a sharp reduction in radiation standards, expedited approval by the NRC of nuclear plant license applications, and a demand to quadruple nuke power in the United States—from the current 100 gigawatts to 400 gigawatts in 2050. Such a move would require huge federal subsidies and the virtual obliteration of safety regulations. Trump has essentially ordered the NRC to “rubber stamp” all requests from a nuclear industry in which he is now directly invested.

Trump’s Truth Social’s fusion ownership stake removes all doubt about any regulatory neutrality. No presently operating or proposed US atomic reactor can be considered certifiably safe.

Trump’s fusion investments are also bound to escalate Trump’s war against renewable energy and battery storage, the primary competitors facing the billionaire fossil/nuke army in which the Trump family is now formally enlisting. That membership blows to zero the credibility of any claim nuclear reactor backers might make that atomic energy can officially be considered safe.

The NRC has long served as a lapdog to the atomic power industry. The acronym NRC has often been said to stand for “No Real Chance” or “Nobody Really Cares.” The commission has been forever infamous for granting the industry whatever it might want, no matter the risk to public safety. It has employed some highly competent technical staff, lending some gravitas to the industry’s marginal claims to even a modicum of competence.

But the NRC is well known for trashing even its established staff. Most notable may be the case of Dr. Michael Peck, a long-standing site inspector at California’s Diablo Canyon twin-reactor nuclear power plant. In an extensive report, Peck warned that Diablo might be unable to withstand a likely earthquake. The NRC trashed his findings. Now he’s gone from the agency altogether. His warnings have been ignored at a reactor site surrounded by more than a dozen confirmed seismic faults.

The splitting of the atom, fission, is the way the atomic bomb and nuclear power plants up to now work. Fusion involves fusing light atoms. It’s how the hydrogen bomb works, and it comes with many extremely complex health, safety, economic and ecological demands.

In an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Dr. Daniel Jassby, for 25 years principal research physicist at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab working on fusion energy research and development, concluded that fusion power “is something to be shunned.”

His piece was titled “Fusion reactor: Not what they’re cracked up to be.”

“Fusion reactors have long been touted as the ‘perfect’ energy source,” he wrote. And “humanity is moving much closer” to “achieving that breakthrough moment when the amount of energy coming out of a fusion reactor will sustainably exceed the amount going in, producing net energy.”

“As we move closer to our goal, however,” continued Jassby, “it is time to ask: Is fusion really a ‘perfect’ energy source? After having worked on nuclear fusion experiments for 25 years at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab, I began to look at the fusion enterprise more dispassionately in my retirement. I concluded that a fusion reactor would be far from perfect, and in some ways close to the opposite.”

“Unlike what happens” when fusion occurs on the sun, “which uses ordinary hydrogen at enormous density and temperature,” on Earth “fusion reactors that burn neutron-rich isotopes have byproducts that are anything but harmless,” he said.

A key radioactive substance involved in the fusion process on Earth would be tritium, a radioactive variant of hydrogen. Thus, there would be “four regrettable problems”—“radiation damage to structures; radioactive waste; the need for biological shielding; and the potential for the production of weapons-grade plutonium 239—thus adding to the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation, not lessening it, as fusion proponents would have it,” wrote Jassby.

About nuclear weapons proliferation, “The open or clandestine production of plutonium 239 is possible in a fusion reactor simply by placing natural or depleted uranium oxide at any location where neutrons of any energy are flying about. The ocean of slowing-down neutrons that results from scattering of the streaming fusion neutrons on the reaction vessel permeates every nook and cranny of the reactor interior, including appendages to the reaction vessel.”

“In addition, there are the problems of coolant demands and poor water efficiency,” Jassby continues. “A fusion reactor is a thermal power plant that would place immense demands on water resources for the secondary cooling loop that generates steam, as well as for removing heat from other reactor subsystems such as cryogenic refrigerators and pumps….In fact, a fusion reactor would have the lowest water efficiency of any type of thermal power plant, whether fossil or nuclear. With drought conditions intensifying in sundry regions of the world, many countries could not physically sustain large fusion reactors.”

“And all of the above means that any fusion reactor will face outsized operating costs,” he wrote. “To sum up, fusion reactors face some unique problems: a lack of a natural fuel supply (tritium), and large and irreducible electrical energy drains….These impediments—together with the colossal capital outlay and several additional disadvantages shared with fission reactors—will make fusion reactors more demanding to construct and operate, or reach economic practicality, than any other type of electrical energy generator.”

“The harsh realities of fusion belie the claims of proponents like Trump of ‘unlimited, clean, safe and cheap energy.’ Terrestrial fusion energy is not the ideal energy source extolled by its boosters,” declared the scientist.

Of course, for Trump, whether it has to do with tariffs, health care, affordability, the democratic process…and on and on, reality is not a concern, especially when they involve public safety or legitimate profit.

Amidst his escalating attacks on renewable energy and atomic safety, the Trump family’s investments in nuclear fusion live under an ominous cloud that threatens us all.

The post Trump’s Nuclear Obsession appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Our 20 favourite pieces of in-depth reporting, essays and profiles from the year

Victor Pelevin made his name in 90s Russia with scathing satires of authoritarianism. But while his literary peers have faced censorship and fled the country, he still sells millions. Has he become a Kremlin apologist?

Continue reading…This post was originally published on Human rights | The Guardian.

When California adopted a law to regulate greenhouse gases 23 years ago — the first state in the nation to do so — it focused on the future dangers of global warming. But while California’s emissions have declined, they have kept rising globally, and the climate has worsened. Now, in an effort to build back momentum, advocates are bringing attention to current-day harms driven by climate change.

Among those affected by rising temperatures is Amanda Nevarez, who was left homeless by the Eaton Fire, one of two wildfires in Los Angeles County that together destroyed more than 16,000 homes and buildings and killed 31 people last January.

The post Climate Change Accelerates California’s Cost-Of-Living Crisis appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

This post was originally published on PopularResistance.Org.

…A dream I had

Of a world all mad.

Not a simple happy mad like me,

Who am mad like an empty scene

Of water and willow tree,

Where the wind hath been;

But that foul Satan-mad,

Who rots in his own head,

And counts the dead–Walter de la Mare, “The Fool Rings His Bells”

We knew it was going to be bad when the tree hit the house. There’d been nearly foot of rain in the last week. The ground was so saturated that the first blast of wind the front in a train of storms uprooted the willow I’d planted twenty years ago, toppling the 30-foot-tall tree. Fortunately for us, being a golden-leaved member of the Salix family the tree, a favorite foraging spot for sapsuckers and woodpeckers that was just beginning to provide cooling late summer shade from the afternoon sun, made a willowy landing and didn’t crash through a window or dent the gutter. The willows fall was a prelude to a coming deluge, the latest in a series of storms that had raked across the Pacific Northwest in December, warm storms cycling up from the tropical Pacific. Climate change? Consider the fact that for most of December, the temperature here 40 miles north of the 45th parallel of latitude, has been 15 degrees above normal. Consider that it’s been so warm, the ski slopes on Mt. Hood at Timberline (6,000 feet) have yet to open, the latest date in more than a century. Even though Oregon escaped the worst of the flooding, all three rivers that converge here in Oregon City–the Willamette, Tualitan, and Clackamas–rose out of their banks, enveloping roads, fields, and homes. The forecast calls for rain in nine of the next 10 days. The climate has changed and will keep changing, faster than we can adapt, even if we try, which we aren’t…

Our fallen willow.

Willamette River flood from the Arch Bridge, Oregon City.

Willamette Falls, second second-largest falls by volume in the US, nearly inundated.

The 50-foot drop of Willamette Falls nearly flooded out.

Willamette Falls, pouring through the old power station.

Flood debris at the old Willamette Falls hydro plant, first in the Pacific Northwest.

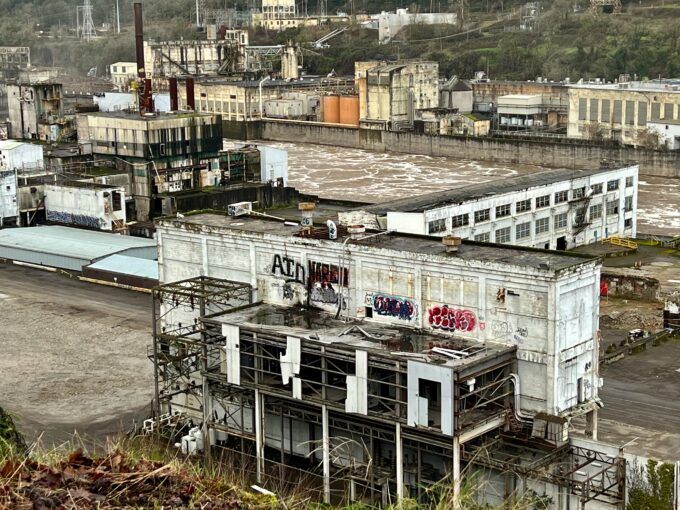

Floodwaters inundate the old Blue Heron paper mill.

Flooding of the Blue Heron paper mill, Oregon City.

Willamette rising up the riverwall at the old Oregon City and West Linn mills.

Floodwaters at the Willamette River locks.

Willamette floodwaters in Oregon City.

Arch Bridge over the flooded Willamette, looking toward West Linn.

Willamette floodwaters extend more than 1,000 feet from their normal course, in Oregon City.

Willamette flooding in Oregon City.

Willamette River flooding in Oregon City.

Clackamas River flooding below the Oregon City Bridge.

Clackamas River flooding in Oregon City.

Flooded pump house along the Willamette, Lake Oswego.

Oswego Creek flooding at George Rogers Park, Lake Oswego.

Flooded road along the Tualitan River.

Flooding of Abiquiu Creek, Willamette Valley.

Flooding of Pudding River, Willamette Valley, Oregon.

Flooding of Molalla River, Willamette Valley, Oregon.

Oregon live oak on the cliff above flooded Willamette Falls, near the site where five Cayuse men were wrongly hanged in 1850.

The post Après le Déluge, un Autre Déluge: a Photo Essay appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Temuco, Chile Penitentiary, where many Mapuche political prisoners are being held. Photo: Langellephoto.org (2024)

In Wallmapu, Chile, the situation of Mapuche youths Lientur Millacheo and Jaime Huenchuñir—the first individuals in Chile to be prosecuted under the country’s newly revised Anti-Terrorism Law—has worsened, according to their spokeswomen. Both young men are currently held in the Temuco Penitentiary, where their families report that they have been subjected to torture and what they describe as direct political persecution by the Chilean State.

We spoke with spokeswomen Alen Huenuche and Millaray Huenchuñir, as well as attorney Christian Arancibia, who is supporting the families.

Millacheo and Huenchuñir remain in pretrial detention while prosecutors investigate their case under the new anti-terrorism framework—and could be legally held without trial for up to five years. In response, the Juana Millahual and Taiñ Meli Bolil Mapuche communities have issued a call for national and international solidarity, denouncing what they see as a politically motivated judicial process.

Despite being recognized as Mapuche comuneros (community members), the two youths are being held with the general prison population. According to their spokeswomen, prison authorities have refused to transfer them to the Mapuche module, claiming that they do not meet internal prison requirements.

From Criminal Charges to Political Imprisonment

For the families and their communities, this case goes beyond ordinary criminal prosecution. The spokeswomen argue that the government’s direct involvement has transformed the case into one of political imprisonment:

When the government invokes the anti-terrorism law and files a lawsuit, it becomes political imprisonment. These are not common crimes—they are linked to territorial reclamation and the criminalization of Mapuche resistance.

Attorney Christian Arancibia agrees, describing the case as part of a long-standing pattern of state harassment against Mapuche communities. He contrasts the harsh treatment of Mapuche defendants with the leniency often shown toward individuals accused of economic or corporate crimes.

Impact of the Anti-Terrorism Law: Facing 20 to 40 Years

The application of the Anti-Terrorism Law has had immediate consequences for the youths’ right to due process. According to their spokeswomen, the law allowed prosecutors to delay judicial oversight and restrict transparency:

“Normally, a detention control hearing takes place the next day. Under this law, it was postponed for five days. That gave prosecutors more time to investigate, add charges, and seal the case, preventing public access to the hearing.”

The long-term consequences are even more severe. Under the anti-terrorism framework, prosecutors may extend the investigation for up to five years, and potential sentences range from 20 to 40 years in prison—a prospect that has deeply affected the families of the youths.

According to Radio Biobío, the youths are accused of involvement in an attack on a forestry company, including arson, robbery, and weapons possession. Prosecutors have also alleged—through media statements—that the two are members of the organization Weichan Auka Mapu (WAM), a claim strongly disputed by their defense and communities.

Attorney Christian Arancibia’s Assessment

Attorney Arancibia describes the case as emblematic of a broader state strategy involving prosecutors, courts, police, and the military to systematically persecute and imprison Mapuche people. One of the youths, he notes, is only 20 years old and was still completing secondary school at the time of his arrest.

Arancibia links the militarization of Mapuche territory to counter-insurgency doctrines rooted in the School of the Americas, where social and political dissent is framed as an “internal enemy.” He further points out that under President Gabriel Boric’s prolonged State of Exception—now longer than any period outside the Pinochet dictatorship—civil authority in the Arauco Province (where Mapuche land reclamation efforts have been very strong) has been effectively transferred to the Navy.

This environment, he argues, has enabled widespread abuses and the erosion of the presumption of innocence.

Allegations of Torture, Water Boarding and Unlawful Coercion

One of the most serious elements of the case involves allegations of torture during the youths’ arrest by the Navy and GOPE (Special Police Operations Group). According to Arancibia, their testimony describes treatment reminiscent of methods used during the dictatorship:

They were beaten, had weapons pointed at their faces, shots fired near them, and were subjected to ‘submarine’ torture—having their faces submerged in water to induce drowning—while officers laughed, spat on them, and continued the abuse.

Arancibia believes the severity of the charges is intended to obscure these violations and protect those responsible:

The State intensifies the accusations in order to prevent accountability for torture and unlawful coercion.

A Dangerous Precedent Under the Current Government

The case also sets a troubling legal precedent. Arancibia highlights that the five-day extension of detention was applied without the youths being brought before a judge, something human rights lawyer Carolina Changdescribed as unprecedented under Chilean law—even in anti-terrorism cases.

Following recent reforms under the Boric administration, Arancibia argues that the legal threshold for labeling an act as “terrorist” has been dangerously lowered. He questions why prosecutors chose this path when serious charges such as arson already carry long sentences, concluding that the decision reflects a political motive rather than a legal necessity.

Prison Authorities and the Denial of Mapuche Status

Although the court ordered their transfer to Temuco Prison, prison authorities have refused to place the youths in the Mapuche comunero module. Officials argue that the alleged crimes are not “Mapuche-related” and cite overcrowding.

Arancibia rejects this reasoning, pointing to a fundamental contradiction:

The State applies the anti-terrorism law, yet denies that these youths are political prisoners. Their own communities recognize them as Mapuche—sons, brothers, and grandchildren of Mapuche families, with social, spiritual, and political ties to their people.

Originally published in Spanish in Resumen. Translation by Global Ecology Project. For more information and/or to get involved, please visit: https://globaljusticeecology.org/chile/

Editor’s Note

Wallmapu refers to the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people in southern Chile and Argentina. The Mapuche are the largest Indigenous nation in Chile and have long organized for recognition of their territorial, cultural, and political rights. In recent years, Chilean governments have increasingly applied security and anti-terrorism laws in Mapuche territories, a practice widely criticized by human rights organizations for criminalizing Indigenous land defense and social protest. Much of the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people in Chile was stolen under the Pinochet Dictatorship, deforested, and transformed into industrial plantations of pine and eucalyptus.

The post Chile Applies New Anti-Terrorism Law to Mapuche Youths; Prison Denies Basic Rights appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Temuco, Chile Penitentiary, where many Mapuche political prisoners are being held. Photo: Langellephoto.org (2024)

In Wallmapu, Chile, the situation of Mapuche youths Lientur Millacheo and Jaime Huenchuñir—the first individuals in Chile to be prosecuted under the country’s newly revised Anti-Terrorism Law—has worsened, according to their spokeswomen. Both young men are currently held in the Temuco Penitentiary, where their families report that they have been subjected to torture and what they describe as direct political persecution by the Chilean State.

We spoke with spokeswomen Alen Huenuche and Millaray Huenchuñir, as well as attorney Christian Arancibia, who is supporting the families.

Millacheo and Huenchuñir remain in pretrial detention while prosecutors investigate their case under the new anti-terrorism framework—and could be legally held without trial for up to five years. In response, the Juana Millahual and Taiñ Meli Bolil Mapuche communities have issued a call for national and international solidarity, denouncing what they see as a politically motivated judicial process.

Despite being recognized as Mapuche comuneros (community members), the two youths are being held with the general prison population. According to their spokeswomen, prison authorities have refused to transfer them to the Mapuche module, claiming that they do not meet internal prison requirements.

From Criminal Charges to Political Imprisonment

For the families and their communities, this case goes beyond ordinary criminal prosecution. The spokeswomen argue that the government’s direct involvement has transformed the case into one of political imprisonment:

When the government invokes the anti-terrorism law and files a lawsuit, it becomes political imprisonment. These are not common crimes—they are linked to territorial reclamation and the criminalization of Mapuche resistance.

Attorney Christian Arancibia agrees, describing the case as part of a long-standing pattern of state harassment against Mapuche communities. He contrasts the harsh treatment of Mapuche defendants with the leniency often shown toward individuals accused of economic or corporate crimes.

Impact of the Anti-Terrorism Law: Facing 20 to 40 Years

The application of the Anti-Terrorism Law has had immediate consequences for the youths’ right to due process. According to their spokeswomen, the law allowed prosecutors to delay judicial oversight and restrict transparency:

“Normally, a detention control hearing takes place the next day. Under this law, it was postponed for five days. That gave prosecutors more time to investigate, add charges, and seal the case, preventing public access to the hearing.”

The long-term consequences are even more severe. Under the anti-terrorism framework, prosecutors may extend the investigation for up to five years, and potential sentences range from 20 to 40 years in prison—a prospect that has deeply affected the families of the youths.

According to Radio Biobío, the youths are accused of involvement in an attack on a forestry company, including arson, robbery, and weapons possession. Prosecutors have also alleged—through media statements—that the two are members of the organization Weichan Auka Mapu (WAM), a claim strongly disputed by their defense and communities.

Attorney Christian Arancibia’s Assessment

Attorney Arancibia describes the case as emblematic of a broader state strategy involving prosecutors, courts, police, and the military to systematically persecute and imprison Mapuche people. One of the youths, he notes, is only 20 years old and was still completing secondary school at the time of his arrest.

Arancibia links the militarization of Mapuche territory to counter-insurgency doctrines rooted in the School of the Americas, where social and political dissent is framed as an “internal enemy.” He further points out that under President Gabriel Boric’s prolonged State of Exception—now longer than any period outside the Pinochet dictatorship—civil authority in the Arauco Province (where Mapuche land reclamation efforts have been very strong) has been effectively transferred to the Navy.

This environment, he argues, has enabled widespread abuses and the erosion of the presumption of innocence.

Allegations of Torture, Water Boarding and Unlawful Coercion

One of the most serious elements of the case involves allegations of torture during the youths’ arrest by the Navy and GOPE (Special Police Operations Group). According to Arancibia, their testimony describes treatment reminiscent of methods used during the dictatorship:

They were beaten, had weapons pointed at their faces, shots fired near them, and were subjected to ‘submarine’ torture—having their faces submerged in water to induce drowning—while officers laughed, spat on them, and continued the abuse.

Arancibia believes the severity of the charges is intended to obscure these violations and protect those responsible:

The State intensifies the accusations in order to prevent accountability for torture and unlawful coercion.

A Dangerous Precedent Under the Current Government

The case also sets a troubling legal precedent. Arancibia highlights that the five-day extension of detention was applied without the youths being brought before a judge, something human rights lawyer Carolina Changdescribed as unprecedented under Chilean law—even in anti-terrorism cases.

Following recent reforms under the Boric administration, Arancibia argues that the legal threshold for labeling an act as “terrorist” has been dangerously lowered. He questions why prosecutors chose this path when serious charges such as arson already carry long sentences, concluding that the decision reflects a political motive rather than a legal necessity.

Prison Authorities and the Denial of Mapuche Status

Although the court ordered their transfer to Temuco Prison, prison authorities have refused to place the youths in the Mapuche comunero module. Officials argue that the alleged crimes are not “Mapuche-related” and cite overcrowding.

Arancibia rejects this reasoning, pointing to a fundamental contradiction:

The State applies the anti-terrorism law, yet denies that these youths are political prisoners. Their own communities recognize them as Mapuche—sons, brothers, and grandchildren of Mapuche families, with social, spiritual, and political ties to their people.

Originally published in Spanish in Resumen. Translation by Global Ecology Project. For more information and/or to get involved, please visit: https://globaljusticeecology.org/chile/

Editor’s Note

Wallmapu refers to the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people in southern Chile and Argentina. The Mapuche are the largest Indigenous nation in Chile and have long organized for recognition of their territorial, cultural, and political rights. In recent years, Chilean governments have increasingly applied security and anti-terrorism laws in Mapuche territories, a practice widely criticized by human rights organizations for criminalizing Indigenous land defense and social protest. Much of the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people in Chile was stolen under the Pinochet Dictatorship, deforested, and transformed into industrial plantations of pine and eucalyptus.

The post Chile Applies New Anti-Terrorism Law to Mapuche Youths; Prison Denies Basic Rights appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Gates of the Arctic National Park. Photo: Zach Richter, National Park Service.

Radical? Not me. In a House Natural Resources Committee hearing earlier this year, after one lawmaker finished complaining about “radical environmentalists” a second lawmaker bemusedly opined that no one is just an “environmentalist” anymore; nowadays all environmentalists are radical environmentalists.

Congressional members throwing “radical” around are definitely projecting. To “project” is to unconsciously attribute thoughts and motivations to another instead of acknowledging them as one’s own—often when it might be difficult to accept one’s own qualities, like hypocrisy, duplicity, or greed.

There have always been humans, like me, who appreciate nature-for-nature and not nature-for profit. The far-reaching, extreme action I see—the radical actors, if you will—are the lawmakers wielding the Congressional Review Act (CRA) so a greedy minority can plunder our public lands and leave us to deal with the consequences.

The CRA allows Congress to revoke a new agency regulation (aka a “rule”) with a joint resolution. Once Congress has revoked that regulation and the president has signed the resolution into law, the agency is prohibited from passing a substantially similar regulation to the one just revoked. Only future legislation can override this action.

Congress enacted the Congressional Review Act (CRA) as a negotiated rider to a 1996 budget bill. Senators Harry Reid (D-NV), Don Nickles (R-OK), and Ted Stevens (R-AK) noted in the Congressional record that they were motivated by “complaints” that Congress was passing progressively complex statutory schemes and delegating federal agencies too wide a latitude in enacting those statutes. Helpfully, they provided not even a single example of their concern manifest.

Since the CRA’s inception, however, we’ve only seen Congress wield it as a partisan sword. This is partly because the CRA requires introducing resolutions to revoke agency rules within 60 legislative or session days after agencies notify Congress about the rule, and there has to be the political clout to pass the resolution—including enough votes to override a veto if one political party doesn’t control Congress and the White House. This tends to happen within the first few months of new Congresses where political power has shifted and a new administration that wasn’t in charge when the agency created the rule.

Sword in hand, Congress cut down its first regulation in 2001, only months into the first George W. Bush administration. Voting largely along party lines, Republicans used the CRA to revoke a Clinton-era regulation designed to minimize on-the-job ergonomic risk factors and reduce preventable injuries. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration had studied the topic for 10 years before issuing a regulation—the House voted to extinguish the regulation after just an hour of debate.

The CRA next struck in 2017-2018, when the Republicans once again had unified control of the government. During the first Trump administration, Congress negated sixteen Obama-era regulations with the CRA, including U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service regulations that banned bear baiting and killing bears and wolves in their dens in national wildlife refuges in Alaska. And when the Democrats swept in with unified control in 2021-2022, they struck down three regulations from the previous administration.

The CRA doesn’t attempt to improve agency action—it is designed to destroy regulations with one final dagger through the heart. Congress can’t tweak a rule—it’s an up-or-down vote.

This year, with power once again unified under one party, Congress applied the CRA to kill three public-land management plans. Notably, Congress has not before this year considered land-management plans as rules or regulations. Applying the CRA to these is a novel application of the law, and also a novel interpretation of a “rule.”

Agencies manage our federal public lands with land-management plans. Agency employees spend years developing the plans and taking public comment on them. Longstanding statutes like the Federal Land and Policy Management Act (FLPMA) and the National Forest Management Act (NFMA), both passed in 1976, guide these plans with authorizations and restrictions. They mandate the agencies to manage land for multiple uses with more robust Congressional direction than the CRA’s “Well, we don’t like this” style. Unsurprisingly, land-management plans have many components to achieve multiple goals, permitting activities in certain places while prohibiting them elsewhere. Courts may review these plans to decide whether they comply with environmental laws or whether agencies exceeded their authority under FLPMA or NFMA. While the process certainly isn’t perfect, planning for millions of acres of public land across multiple ecosystems is now at the whim of lawmakers who dislike as little as one plan component.

One of the CRA joint resolutions that Congress has passed and is waiting for the President’s signature nullifies the Central Yukon land-management plan in Alaska, which would have governed over thirteen million acres of land in central and northern Alaska. Three million of those acres were designated as an area of critical environmental concern and overlapped with the Ambler Mining Road proposal, prohibiting it. The Ambler Mining Road would span 211 miles and run adjacent to the Gates of the Arctic Wilderness to connect a mining district to a highway for a private Canadian mining company. The Ambler Road would introduce motorized use to some of America’s wildest public lands. When the President signed H.J.Res. 106 into law on December 11, he removed the administrative hurdle preventing construction of the Ambler Road by obliterating the entire land-management plan. For all public lands, this new application of the CRA injects radical Congressional micro-meddling into agency land-management decisions.

There are lingering questions about how an agency moves forward after Congress strikes with its own extreme prerogative. What else will Congress consider to be “rules?” Can any uses be authorized? Can any uses be restricted? How many components of a plan must change for that plan to clear the CRA’s prohibition on creating a “substantially similar” regulation? Congress has launched us into a labyrinth of uncertainty. If discarding robust land-management plans that were developed with public participation under laws in existence for 50 years isn’t radical, then I don’t know what is.

The post The Congressional Review Act: A New Tool for Lawmakers to Radically Meddle in Public Land Management appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.

Clifty Coal Power Plant, Madison, Indiana. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

As projections of U.S. electricity demand rise sharply, President Donald Trump is looking to coal – historically a dominant force in the U.S. energy economy – as a key part of the solution.

In an April 2025 executive order, for instance, Trump used emergency powers to direct the Department of Energy to order the owners of coal-fired power plants that were slated to be shut down to keep the plants running.