The following is a shortened, lightly edited excerpt of a speech given by Australian politician, diplomat, gender equality advocate and author Natasha Stott Despoja AO, at the National Foundation for Australian Women annual dinner, 2023. Natasha is currently a Professor in the Practice of Politics at the ANU. She’s also an elected member of the UN’s Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

What an honor to address this dinner with some reflections on the state of gender equality in Australia and globally.

I use the reference to the Matildas during this difficult time globally, as one of the great highlights of this year has been the successful Women’s World Cup which brought our nation together and highlighted women’s leadership and prowess.

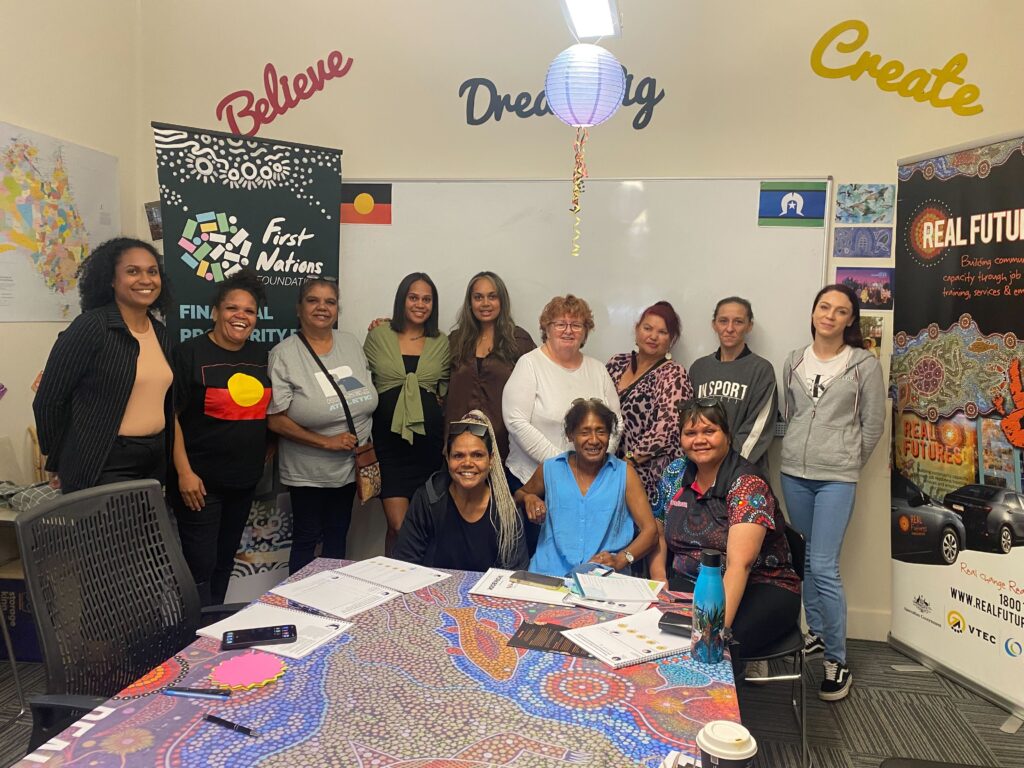

Tonight, I pay particular tribute to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women tonight, especially those who championed The Voice.

It was a profound experience to be on the Prime Minister’s Referendum Council and see the painstaking work and collaboration that went into the Uluru Statement from the Heart and – like many of you – I express my despair at the result.

From an international perspective, it was concerning to see how my UN colleagues reacted. The specificity of the referendum was lost, but the general message of the rejection of the rights and recognition of Indigenous Australians is a narrative that understandably has currency in some multilateral spaces.

My not-for-profit work these days involves protecting and advancing the rights of women and girls in UN Member States as a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). I have just returned from State Party dialogues with countries ranging from Uruguay to France, Albania to Malawi.

Regardless of the differences, no country has achieved gender equality, including Australia.

Yet, no country or community, regardless of its circumstances, can reach its full potential while drawing on the skills of only half its population.

This session was particularly daunting: I spoke with families of the hostages in Israel as well as Palestinian and Israeli feminist NGOs terrified about the welfare of their friends and people as well as the disproportionate impact of war and terror on women and girls.

We continue to see examples of the deterioration of women’s human rights globally: and the impact and prevalence of Conflict Related Sexual Violence in conflicts such as the Middle East, Afghanistan, DRC, Sudan, Ukraine.

Despite the crises occurring globally, and the backlash against women and girls, our seat at the table is still missing, especially in peace negotiations.

This is in spite of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and subsequent resolutions on ‘Women, Peace and Security’ which acknowledge “the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peace-building” and insisted on the increased participation of women in all stages of a peace process, including peace negotiations.

We know there is a strong correlation between peace agreements signed by female delegates and durable peace and yet, seven out of every ten peace processes do not involve women mediators or signatories.

In the multilateral sphere, we are not only dealing with countries which have been slow to advance gender equality, we are now confronted by countries actively backtracking.

The High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Turk, has warned about the “pushback and backsliding”, the “systematic countering of women’s rights and gender equality”.

On IWD, the UNSG Antonio Gutteres said, “the patriarchy is fighting back”, warning it would take 300 years to achieve gender equality at the current pace.

The covid pandemic also exacerbated existing inequalities and made the lives of those already marginalised — including the poor, people with disabilities, and women and girls, much worse.

Before COVID, approximately 244 million children were out of school, mostly girls. Now, the education of almost 1.5 billion young people is at risk.

As a result of the pandemic, over the next decade, up to 10 million more girls will be at risk of becoming child brides.

These examples remind us that everything is relative and of course Australia is doing comparatively well. But, the enduring comment I get from my UN colleagues about Australia is that they are surprised that we are not doing better!

The reality remains that when it comes to gender parity in Australia: women are still paid less for the same work, are more likely to engage in part-time and casual work, carry the primary responsibility for care-giving, for both children and parents, and retire with less superannuation.

These situations are compounded for women from poorer, diverse and Indigenous backgrounds and for women with disabilities.

Women represent less than 36% of board positions, there are only 10 female CEOs of ASX 200 companies; women comprise 20% of the ADF workforce and until recently, Australia had fewer women in its highest ranks of government than nearly every OECD country.

Yet, we know that an increased number of women in leadership roles leads to improved distribution of resources, better maintenance of public infrastructure, better natural resource management, and actually has a positive effect – right down to measures as simple as profit and loss.

Companies with more women in senior management teams have about 30% higher profit margins than those with lower gender diversity.

The business case is compelling. As Sam Mostyn and the Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce has made clear, a tax system that eliminates “negative gender biases” could unlock $128 billion lost annually to inequality.

Apart from this being the fair thing to do, increasing women’s leadership and voice are the right thing to do.

Research also shows women in leadership positions changes perceptions regarding the roles and aspirations of girls (including reducing the time girls spend on household chores in developing countries), results in more girls attending school and becoming equipped, themselves, to play leadership roles, including in conflict prevention.

We can’t be what we can’t see.

When I became a Senator, so many messages came from young women, saying that “if I could do it so could they”.

That was more than 27 years ago, and the federal parliament was around 14% female, and I was sure that we’d have gender parity long before now.

I take heart in recent changes: there are more women than ever before, 4% of MPs are of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, and we have more diverse cultures and backgrounds reflected and represented. The Senate is now 53% female.

I was serious about changing public perceptions around who was a politician (male, white, privileged, older) and worked with others to change the policy landscape for women generally, and the culture of the parliament specifically. I dealt with ridiculous stereotypes, unsolicited comments and touching, double standards and discrimination.

Being a younger woman underscored these experiences, but no woman is exempt, and these experiences are compounded for women of color, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, lesbian and trans-women and for women with disabilities.

All of whom have been profoundly under-represented in our decision-making institutions and whose injustices deserve bolder attention. Along with those of older women, the fastest growing group moving into poverty.

But, as my CEDAW colleague, Nicole Ameline reminds us, it is not just about numbers – and of course reflecting the difference and diversity in our population – but we need serious ‘disruption’ when it comes to decision-making institutions and ‘systems’.

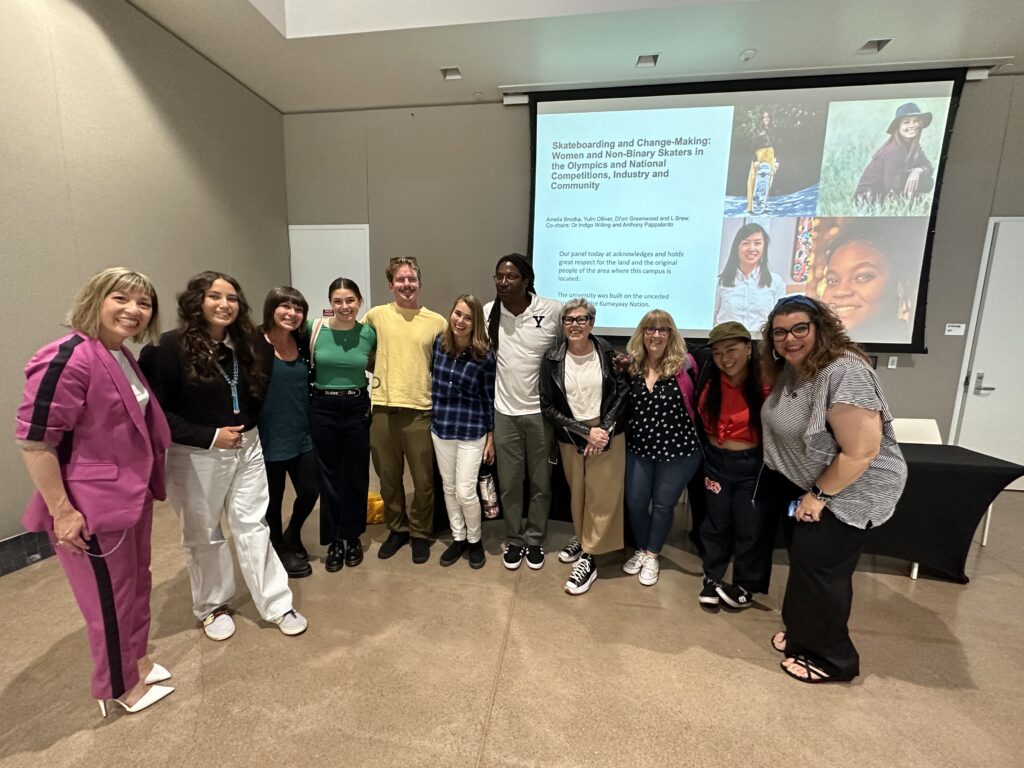

Left to right, Jane Madden, President of NFAW, Zali Steggall MP, Natasha Stott Despoja, Aunty Violet Sheridan, Ngunnawal elder, Stephanie Copus Campbell, Ambassador for Gender Equality, Zoe Daniel MP, Sally Moyle, Vice President of NFAW and Mary Atkinson, Ngunnawal elder. Picture: Supplied

This is the rationale behind Madam Ameline’s GR 40 which calls for a “paradigm shift towards parity as a key norm in support of the realisation of women’s rights to equal inclusive and meaningful representation in decision making systems at all levels of the CEDAW Convention”.

These changes are those that the National Foundation for Australian Women has been calling for since its inception.

Your admirable goal of advancing and protecting the interests of Australian women in all spheres, including intellectual, cultural, political, social, economic, legal, industrial and domestic has been pioneering.

And, importantly, you goal is to ensure that the aims and ideals of the women’s movement, and its collective wisdom, are handed on to new generations of women.

It is an honor to be the dinner speaker for this pioneering feminist organisation which I have watched and been honored to connect with since it began. I have admired its founders, including the late Pamela Denoon, and its members. NFAW is one of the most important bodies in contemporary feminist herstory.

Your work on a gender-lens on budgeting and social policy, the women’s archives and other projects have made Australian women’s lives better and have guided and held accountable governments of all persuasions. I thank you.

We still have a long way to go before we have a more gender equal future. 300 years is shameful statistic.

But it is not easy when 59% Australians believe that gender equality has mostly or already been achieved.

Only 26% disagreed that women are more naturally suited to be the main carer of children and elderly parents – 37% agree with this statement, and 37% are ‘on the fence’.

Just 53% agree that it is important for Australians to stand up for gender equality in other countries. I am particularly proud of the work that Australia does, especially in partnership in the Pacific.

We have to tackle the historically-entrenched beliefs and behaviours that drive gender inequality, and the social political and economic structures, practices and systems that support this inequality.

That means we have to make changes in all the areas in which we live, love, learn work and play!

Speaking of play… it brings me to sport, and my initial comments. A feature of our State Party dialogues has been the increasing acknowledgement of the role of women in sport. In many areas it has undergone some of the most exciting gender revolutions in recent times.

I cried on the inaugural night of the AFLW back in 2017. And has the same feelings as I watched the opening night of the WWC2023. The WWC 2023 was the biggest women’s single-sporting event in the world with ticket sales smashing the previous Women’s World Cup ticket record.

As a consequence, we have seen greater investment in women’s football and an emphasis on gender equality. And we may be sceptical about some countries. In 2018 women couldn’t enter a stadium in Saudi Arabia and now there’s investment in a national women’s team.

I loved watching young girls and boys, mostly in their Sam Kerr shirts, at the game and clamouring for photos and autographs.

I loved this Matilda effect.

I do note that there is an actual Matilda effect: it is a bias against acknowledging the achievements of women scientists whose work is attributed to their male colleagues.

Australia celebrates a goal during the International Friendly Match between Australia and Canada at Allianz Stadium on September 6, 2022 in Sydney, Australia. Picture: Shutterstock

And who would have thought the actions of a man would overshadow the greatness of this event? Football boss Luis Rubiales’ forcible kiss of Women’s World Cup player Jennifer Hermosa — was an abuse of authority and reminded us how women – even in the highest echelons of their sectors or professions – can be subject to inappropriate and abusive actions.

But these actions were called out and condemned globally. Increasingly, I take great heart from the brave young and diverse women calling out bad behaviour and holding perpetrators to account.

I think NFAW’s mission to ensure that the aims and ideals of the women’s movement and its collective wisdom are handed on to new generations of women is in good hands.

But the price of feminism is eternal vigilance, something NFAW has been aware of for decades.

There are many hard won rights that we must protect and advance, in spite of the global backlash.

Friends, this is not a women’s problem: this is everybody’s business.

And I thank you all for being a part of this mission!

- Picture at top: Natasha Stott Despoja during a welcome reception at ANU, in Canberra, ACT, Australia, 05 September, 2022. Photo: Tracey Nearmy/ANU

The post Waltzing Matildas: How is Australia Faring on Gender Equality? appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.