Former Channel 4 Editor at Large Dorothy Byrne says lazy generalisations can make women feel disempowered and undermine their ambitions. She gave this speech at the recent national Women in Media conference on the Gold Coast. It’s published here with full permission. Read the original here.

I’m thrilled to be here among you at the conference of an organisation I admire very much for the support it gives women in the media. Organisations like yours are vital for women. I come here to bring you my personal perspective on what I feel are the key issues for women in journalism today. I’ve been a journalist for 46 years and I’m convinced these are great times to be a woman journalist.

When I started out on a local paper, the number of women going to work in newspapers in the UK was slightly greater than the number of men.But, over the years women fell by the wayside until women were in the minority, to a significant degree, for a variety of reasons. In my early days, all the most important jobs were held by men.

‘I had no role models’

Indeed, on my first paper the sexism was so bad that only men were allowed to cover major crimes. As a woman, if there was a murder, I was permitted only to interview the relatives of the victims while the male journalists got to investigate the murder itself. That lack of opportunity hampered the career development of women but the fact that the key roles on the paper were all held by men also restricted our ambition.

I ended up as the Head of News and Current Affairs at one of the UK’s main public service broadcasters. That young woman of 24 on the Walthamstow Guardian in East London would never have dreamt such a thing could be possible. I had no role models. But today in the UK things are very different.

Women starting out today can aim for the top

The new head of news and current affairs at Channel Four Television, who replaced me, is a woman. The editor of Channel Four News is a woman and the editor of Channel Four’s main investigative current affairs programme is a woman. The chief executive of Independent Television News which makes news for both ITV and Channel Five is a woman as was her predecessor.

And finally, the Head of BBC News is a woman as was her predecessor. So a young woman starting out in journalism today knows she can aim for the very top and get there.

That is a big change but of course, there are huge barriers for women.

Motherhood and the menopause

Still too many women are dropping out of journalism at different stages in their careers.

One of the key reasons is that work in many newsrooms and programmes is incompatible with motherhood but today I will also highlight an issue now at the forefront of debate among women journalists in the UK; the menopause.

If you take away only one thing from my talk today, please take away the need for women journalists to lead the discussion in Australia about the menopause. As women journalists, we did that in the UK and it was so transformational that this year Britain ran out of one of the most popular forms of HRT.

But first things first; the dire state of maternity rights and childcare in the UK. Of course, poor maternity rights have always been a major barrier for women but there is a specific issue making it worse for female journalists at the present time.

A ‘physically overwhelming’ longing

In the UK good maternity rights are tied to staff jobs but more and more jobs in journalism are freelance so fewer and fewer women journalists get proper maternity pay.

I myself was freelance when I had a baby as a single parent. As such, I was entitled only to basic state maternity pay which was not nearly enough to pay even a percentage of my mortgage. So I had to go back to work when my child was less than six weeks old.

It was terrible.

My longing for my baby would be so physically overwhelming at times that I had to ring her nanny and tell her to bring my daughter to the office as a matter of urgency just so I could hold her.

Too many women face a tough choice

But note, I delayed having a baby until I could afford a live-in nanny. I was lucky to get pregnant at 45, once my career was established.

Too many young women today feel they have to choose between building their careers or having a baby in their late 20s and early 30s when their statistical chance of getting pregnant is higher than when they are in their late 30s or early 40s.

This issue is not talked about nearly enough because young women fear that if they talk about their desire to have a baby, it will affect their promotional opportunities.

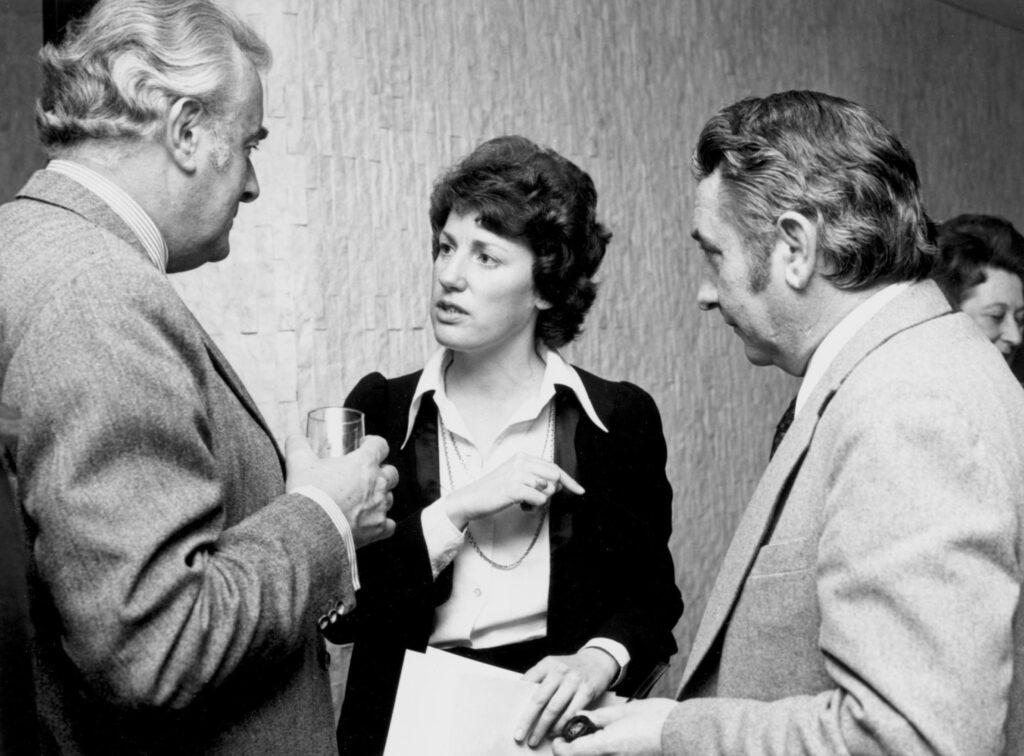

Dorothy Byrne has been a journalist for 46 years. Photo: Emma Brasier.

A number of young women journalists have told me that they really want to have a baby soon but feel they just can’t afford it both financially and in terms of their career opportunities. They have asked me not to tell anyone about the conversation I have had with them because they fear it would prejudice their chances of promotion.

That is scandalous and deeply depressing.

Paying ‘lip service’ to flexible working

I think older women should encourage open discussion of issues around fertility, pregnancy, and childcare in newsrooms to signal to young women that in a good organisation their right to have a child will not damage their career. Similarly, we need as women to insist major employers have proper policies on returning to work.

Women in the UK are campaigning for proper statutory maternity and paternity pay for all women, not linked to a staff job, as a right. Until we have that, there will be no equality in the workplace.

And all employers need to examine their working practises and investigate whether their current shift patterns are really necessary.

Too often employers pay lip service to the notion of flexible working but don’t ask themselves basic questions such as, ‘Does everyone on the early shift really have to turn up at the same time? Could we stagger our shift systems better?’

My first day in television

Big policies are great, small practical changes are better. Female journalists also continue to suffer harassment and assault at work both from bosses and colleagues AND from men they are interviewing.

But here there is some improvement. When I started out on local papers, women spoke openly in the office about being sexually harassed by police officers.

I am not aware of a single instance in which an editor complained to the police.

On my first day in television, my female boss told me that a director would take me out to show me the basics of filmmaking – and that he would sexually assault me. But I was not to take it personally because he sexually assaulted all the women he worked with. Sure enough, he assaulted me but who could I complain to as I had been told by my manager to expect this?

I don’t believe that would happen now at a major employer, although I think young women especially are still vulnerable because so many people now work in very small companies where there is much less protection. Employers should not send women to interview men with a reputation for assaulting women.

Some men with known reputations for sexual assault and harassment are being interviewed purely to publicise their films, books or other enterprises. Media outlets should refuse to send anyone to interview men who are known to prey on female journalists.

Now bigger employers have sexual harassment policies and women journalists, some well-known, have started to talk publicly about having been assaulted.

But journalism in the UK awaits its #MeToo moment. There are leading men known to have harassed and assaulted women who still have high journalistic reputations.

‘You probably don’t remember me Dorothy’

If just a few of those top names were exposed, it would make a big difference. It would make men think twice. I myself, when a program producer, was assaulted in my own home by a man who ran a production company we were doing business with.

Later, when I had risen to become a senior program commissioner at Channel Four, he had the gall to turn up at a session I held for production companies. At the end of my presentation, he stood to ask a question and, with a leer on his face, said, ‘You probably don’t remember me Dorothy.’

I said, ‘On the contrary, how could I forget a man who sexually assaulted me in my own home.’ The whole room glared at him and he sat down and shut up.

We need to warn such men. Tonight, you may see a woman as your victim, but she could be your boss tomorrow.

It’s not for me to tell Australian broadcasters what to do but I can talk about my own country.

In the UK broadcasters lay down a range of requirements for production companies supplying programs to them and I think they should include a clause stating that any production company proven to have tolerated or covered up sexual harassment would automatically be in potential breach of contract.

But those are the negatives.

My fear for women journalists now is also that we are not being sufficiently positive and that we may therefore inadvertently put off young women from entering journalism by failing to emphasise what a brilliant and exciting career it can be. We now expose the sexism women in the media face. That didn’t happen before.

The wrongs done to us were accepted or relayed to each other in the evenings. They were not spoken out loud in the corridors of power by newsroom leaders. Now they are.

But we also need to be careful to talk about what’s great about being a woman in the media. I am now the President of Murray Edwards College at Cambridge University.

It’s a women’s college and quite a number of students are interested in a media career. I encourage them. One of my first points is that I am still a working journalist at the age of 70.

In the past year, I have been executive producer on an international series about the sexual predator Ghislaine Maxwell, a major documentary on the Russian dissident Navalny and an expose of sex abuse in the Falkland Islands. I am currently working on a major series on Kevin Spacey.

‘I don’t think I will ever retire‘

Almost all my friends in other professions retired several years ago. Some went into highly lucrative jobs in the City of London after university. They retired as soon as they possibly could. Most doctors and teachers I know retired early, in their mid-50s. In contrast, I don’t think I will ever retire as a journalist. Why would I?

To be a journalist is to have the opportunity to explore the great experiences life has to offer and to expose the bad ones.

Conference delegates applaud Dorthy Byrne. Photo: Emma Brasier.

Better rights for women

To be a woman journalist is to have a wonderful opportunity to change lives for all women in society. In my career, some women have told me they don’t want to be pigeon-holed into being defined as someone who does so-called women’s stories.

They want to be thought of as a journalist, not as a woman journalist. In fact, they shied away from doing so-called women’s stories. I get their point.

I too don’t want to do just women’s stories. But I definitely want to use my role as a journalist to campaign for better rights for women.

Telling women’s stories

The first film I produced and directed was about rape in marriage, then not a crime in the UK. Husbands could be charged only with causing injury during the rape. That film was part of a successful campaign, which changed the law.

Over the years a significant part of my work has been about women and girls -rape, domestic violence, female genital mutilation, the denial of education, poor maternity care, and the mental health crisis among girls.

That sounds like a grim list but it’s been thrilling to see how issues I have raised have been taken up in public and political debate; to have been part of making life better for women.

This has been work which has brought me great fulfilment in my life. I’ve been proud to be thought of as a woman journalist.

I would ask women who worry about being pigeon-holed if we don’t raise women’s issues, do you think men will do so? If we as women don’t tell women’s stories, those stories won’t be told at all.

We should be sure we tell young women thinking about a career in the media that being a woman journalist is a magnificent thing. I also think that we need to be careful in our language not to put ourselves down as women.

There are enough men who want to put us down; we don’t need to do it ourselves. Over the years, I have often been asked if I suffer from so-called imposter syndrome and even more often I’ve heard women say, ‘We all, as women suffer from imposter syndrome’.

I say to them, speak for yourselves. If you have imposter syndrome, that’s fine. I respect your perspective on life.

But I certainly DON’T have imposter syndrome. I’ve been a journalist for 46 years, for God’s Sake. Why would I have imposter syndrome? I’m the real deal.

I feel the same objection when I hear people say, ‘Women lack confidence. Women are always putting themselves down.

‘Women aren’t pushy.’

Do I seem to you like a woman who lacks confidence or puts herself down?

I don’t seek to be pushy. But if you push me, I’ll push back.

Lazy generalisations

What people really mean is that women are statistically less likely to, for example, apply for jobs when they don’t have all the qualifications, speak up in meetings, ask for a pay rise.

We should talk about those statistics and about how we can encourage women. But we shouldn’t confuse learned behaviour with the false notion that women are inherently so different to men. We are different to men but a lot of those differences are instilled in us by a sexist society.

Lazy generalisations in sentences that begin with the words, ‘Women are… ‘ can end up making young women feel disempowered and undermine their ambitions.

In my experience in journalism, women have taken longer to get to the top jobs than have men.

Women need to support each other

We have had to work harder to get to the same place as a man. I’ve told my own daughter that my single greatest piece of advice to her is, ‘Don’t work as hard as I have.’ We want talented young women to have the same fast track to the top that their male counterparts have benefited from.

To do that we have to imbue them with a sense of self confidence, not emphasise their lack of confidence. Organisations like your own are vital. Women need to band together to support each other and campaign for equality.

‘These people are wrong’

There is a view that women’s organisations are no longer needed. I lead a women’s college at Cambridge University now, as well as being a working journalist.

As far as I am aware in the UK, there are only two all-female higher education institutions left; Murray Edwards College which I lead and another at Cambridge. People say to be that the idea of a women’s institution is outdated.

But when they tell me that I always say, ‘Wow! Equality for women has been achieved and I missed it! I must have been locked in the toilet or out shopping or having my legs waxed. Who knew?’ Of course, these people are wrong.

Same degree, different outcomes

While the percentage of women entering higher education in the UK is now equal to the percentage of men and slightly greater in some years the percentage of women going on to further degrees is lower than the percentage of men.

Statistically, women with the same degrees as men are likely to have less good jobs.

It reminds me so much of my time starting out in journalism – equal numbers of women at the start – and the gradual attrition.

As a women’s institution, we can campaign publicly about these issues, and highlight some of the reasons for this inequality. And that’s what a great organisation like yours does.

We need to hold onto women’s organisations and encourage more. Thinking back, I would have benefited greatly if there had been an organisation for young women journalists when I started out.

In defence of ‘women’s pages’

I also think that all the newspapers which got rid of women’s pages should think again. Women still suffer from some specific hardships and prejudices.

I am not confident that these issues are dealt with in general pages as well as they would be in a weekly women’s page.

Dorothy Byrne sees value in women’s pages. Photo: Emma Brasier.

I used to turn first to the women’s pages in newspapers because I knew there would almost certainly be something there relevant to my life. In the UK, the Femail pages in the Daily Mail are really popular. Women’s Hour on the BBC is also hugely popular.

And it never feels that it is excluding men; it raises issues that are of interest and concern to anyone interested in women and girls.

Sexist remarks about older women at work

When women journalists use their experience of being women, they can transform society. And I want to give you a brilliant and concrete example of this.

Until a few years ago, the menopause was not recognised as being a major issue affecting women’s lives and careers in the UK. Women going through the menopause and suffering significantly didn’t dare talk about their problems at work for fear of prejudice.

Some men made horrible sexist remarks about older women at work, generally in my experience because those women were better than they were. If an older woman criticised a man, he would scoff to his friends, ‘It’s her hormones!’

A ‘proud old lady’

Companies which had good maternity policies had no policies about the menopause at all. Three years ago, at the Edinburgh Television Festival, I made a major speech in which I highlighted the problems I myself had experienced with the menopause.

I made a deliberate decision to use my experiences to speak out. I introduced myself in the speech as a proud ‘old lady’ and described how my kindly male boss sent me home because I had a ‘fever’ when all I had was hot flushes.

He clearly didn’t recognise a hot flush and I was too embarrassed to put him right. I named him in my talk. I won’t do so again because he’s suffered enough.

‘The menopause’

He certainly knows about the menopause now.

I then gave statistics for the number of women who had considered giving up work because of the menopause – government statistics at the time indicated that about a quarter of women had considered giving up their jobs because of their symptoms.

Somewhat to my surprise I admit, just mentioning the menopause gained huge publicity. Soon afterwards, Channel Four became the first British broadcaster to have a comprehensive menopause policy.

One of my last acts before leaving Channel Four was to commission a film about the menopause presented by the popular presenter, formerly presenter of Big Brother in the UK, Davina McCall who admitted her own problems when she went through early menopause.

Some in my office said the program would get poor ratings as only older women would watch it.

Suddenly everyone was talking about it

I pointed out that there are an awful lot of older women.

In the event, it gained a good audience and a follow-up program was also commissioned.

These programs told the British public the facts about the effects of the menopause.

A survey for Channel Four and the Fawcett Society revealed that 77% of women had experienced one or more symptoms of the menopause they described as very difficult. Forty-four per cent said their ability to work had been affected. A tenth employed during the menopause had left work due to the symptoms. Fourteen per cent had reduced hours or gone part-time and 8% said menopausal symptoms had prevented them from applying for promotion.

Suddenly, everyone started discussing the menopause – men and women – and more companies instituted policies that included training for all staff, medical advice sessions and women being given the right to work less if they felt unwell.

All long overdue.

‘Who’s to blame for this?’

The fact that women have babies was recognised in employment legislation decades ago.

The fact they stop having babies and their bodies change was not mentioned. A major portion of both programs was devoted to giving the facts on HRT – revealing that many women were given poor or erroneous information by doctors whose own knowledge was way out of date.

As a result, there has been a huge surge in demand for HRT by women no longer prepared to be fobbed off and told, ‘It’s natural so you have to live through it,’ or even more offensively, being put on inappropriate anti-depressants. Indeed, this year, one of the most popular forms of HRT started to run out in Britain. As it happens, it’s the form I use.

I got really angry one day when I was told that no pharmacy near me had any and exclaimed inwardly, ’Who’s to blame for this?’ Then I realised it was me.

Power to prompt change

I am pleased to say the crisis has now eased and supplies are coming through again.

I go into some detail about this because I believe the menopause is a major reason older women are leaving the workplace. In the UK, it was because women journalists, using their own personal experience, exposed the issue that women across the country rose up and demanded both HRT and proper policies.

I think it’s a great example of the power for change we have as women journalists if we band together and speak out. We should expose the negatives but we should also shout loudly about our successes.

I’ve been told about some of the exciting plans for your brilliant organisation and I will follow your progress with great interest.

I just wish my 24-year-old self had known a great bunch of women like you.

This is an edited version of Dorothy Byrne’s address to the 2022 Women in Media national conference.

- Feature image at top: Dorothy Byrne addresses delegates at the national conference. Photo: Meg Keene.

The post Banishing imposter syndrome: ‘I’m the real deal’ appeared first on BroadAgenda.

This post was originally published on BroadAgenda.

![Questions: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? Men, women and non-binary people are treated equally in Australian society; Thinking about Australian news in general, how well do you think it covers women? [Base: N=2,266]](https://www.broadagenda.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023-Picture-1-1024x566.jpg)

![Questions: To what extent do you think the Australian news media needs to work on improving diversity? [Base: N=196]; Do you think your news organisation has enough employee diversity in the following areas? [Base: N=193] *Excludes freelancers/contractors; Have you experienced discrimination in your newsroom based on your gender? [Base: N=196]](https://www.broadagenda.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Picture-2-1024x428.jpg)

![Question: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? My news organisation is doing a good job with employee diversity at a… [Base: N=193] *Excludes freelancers/contractors](https://www.broadagenda.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Picture-3-1024x769.jpg)