Until she got her first Pfizer shot on July 16, Cindy Cervantes toiled in the Seaboard Foods pork processing plant in Guymon, Oklahoma for most of the pandemic without a vaccine — working unprotected in an industry devastated by Covid-19 illnesses and deaths.

“In one day, at least 300 people were gone” from the plant, sick from Covid, Cervantes says. Still, “Seaboard wanted a certain number of hogs out. They kept pushing people, the chain was going even faster. People were getting injured, and we were losing even more people.” Six of her coworkers have died from Covid-19, and hundreds have gotten sick, she says.

Ravaged by the pandemic, the roughly 500,000 U.S. workers in meatpacking, meat processing and poultry are not getting much help from the industry or the government. In a sector described as “essential” during the pandemic, at least 50,000 have been infected and more than 250 have died, according to Investigate Midwest, a nonprofit news outlet. Yet amid this grim toll, the North American Meat Institute lobbied successfully to exclude meatpacking and poultry workers from new Covid-19 worker safety rules enacted this June.

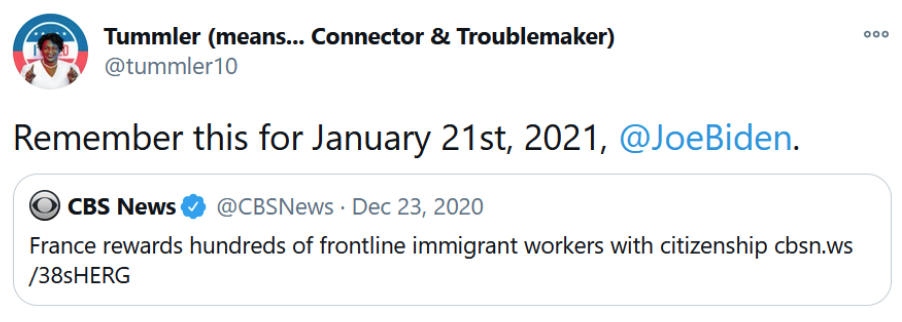

Even as vaccine availability in the United States steadily expands, workers still face pandemic peril on the job, from breakthrough cases of Covid-19, as well as low vaccination rates in many areas due to a combination of misinformation, conspiracy theories, and serious access barriers to immigrants who fear deportation. Workers and advocates are sounding the alarm that President Biden has dropped the ball on pandemic-era worker protections, violating one of the first promises of his presidency. This warning has particular salience after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said Tuesday that some people who are fully vaccinated should wear masks indoors in areas where there are severe outbreaks, due to the spread of the Delta variant.

On his second day in office, Biden signed an executive order promising to enact new emergency safety rules “if such standards are determined to be necessary” by March 15 to protect millions of “essential” workers like Cervantes. The goal was straightforward: to give workers enforceable protections on the job, such as mandating that companies provide physical distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE). But the deadline came and went, with no new rule. Then, on June 10, after heavy lobbying by many industry groups — including the American Hospital Association, the National Retail Federation, the North American Meat Institute and the National Grocers Association — Biden issued a narrow rule covering only health care workers.

This is despite the fact that other industries have been devastated by the pandemic. “Almost all my coworkers have gotten it,” Cervantes says of the virus, noting that many of them were out sick for months, and some returned to work with lingering Covid-19 symptoms. Yet, she says, “a lot of workers I work with have not gotten the vaccination” for a host of reasons. Some are “skeptical,” and “think it’s got a chip in it or that it’s not going to work.”

It’s not hard to get a vaccine at the plant, Cervantes says. But in an industry that relies heavily on immigrants, Latinx and often undocumented workers, there are many barriers to vaccination, researchers note. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “Large shares of Hispanic adults — particularly those with lower incomes, the uninsured, and those who are potentially undocumented — express concerns that reflect access-related barriers to vaccination.” Oklahoma, home to the Seaboard plant where Cervantes works, is among the nation’s most dangerous Covid-19 states, with just 40% of the population fully vaccinated, and “high transmission rates,” according to the CDC.

In an email response to questions, Seaboard communications director David Eaheart said the company “proactively” notifies workers of any Covid-19 cases in the plant, and has taken numerous precautions based on CDC and state health guidance, including paid leave for infected workers, and plexiglass shields at “select line workstations.”

Eaheart acknowledged that in May 2020, testing at the plant identified 440 employees with “active cases of Covid-19,” the plant’s “highest week of reported active cases. All these employees self-isolated at home and were required to follow CDC guidance before being allowed to return to work.” During that week, he said, “overall production was scaled back in the processing plant and fewer animals were processed and products produced.” More than 1000 workers at the plant have tested positive, and six have died, Eaheart confirmed.

Since March 15, when Biden’s promised Covid-19 workplace safety protections were supposed to take effect, more than 15,000 working-age adults have died from the pandemic in the United States, according to the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (COSH). “Every one of those individuals had a family that was also at risk of Covid,” said Jessica E. Martinez, co-executive director of National COSH, in a June 9 press release anticipating Biden’s rule. “Releasing an emergency standard three months late and just for health care workers is too little, too late.”

The original rule drafted by the Department of Labor did cover all workers, as Bloomberg Law first reported—but then the infectious disease standard met the buzz saw of politics and industry pressure, and the White House opted to cover health care workers only.

As the Department of Labor’s draft standard stated, “For the first time in its 50-year history, OSHA faces a new hazard so grave that it has killed more than half a million people in the United States in barely over a year, and sickened millions more. OSHA has determined that employee exposure to this new hazard, SARS-CoV‑2 (the virus that causes Covid-19) presents a grave danger in every shared workplace in the United States.”

Citing rising vaccination rates — 60% of U.S. adults are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC, though just 49% of the population overall — Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh said the new rules focusing on healthcare workers “provide increased protections for those whose health is at heightened risk from coronavirus.” Neither the White House nor the Department of Labor provided any explanation for why other workers in high-exposure jobs were excluded.

“That’s kind of ridiculous,” says Louisiana Walmart worker Peter Naughton. “They should cover retail workers as well. We come into contact with people who may have the virus without knowing it.”

In Louisiana, where new Covid-19 cases are double the national infection rate and vaccinations lag far behind, Naughton, 45, toils in fear every day at a Walmart in Baton Rouge. He got vaccinated in May, but in his job helping customers navigate self-checkout kiosks, Naughton says, “I come into contact with hundreds, possibly thousands, of people a week.” Naughton, who lives in Baton Rouge with his parents to make ends meet, says that despite the recent uptick in Covid-19 cases, and the spread of the extra-dangerous Delta variant, there are minimal safety precautions, and “Walmart is acting like the pandemic is over.”

While the vaccines vastly reduce risk of death or serious illness, infections and “breakthrough cases” are still infecting vaccinated people. And the CDC’s befuddling guidance making masks voluntary for those who are vaccinated, on the honor system, hasn’t helped. Furthermore, the CDC explains, “no vaccines are 100% effective at preventing illness in vaccinated people. There will be a small percentage of fully vaccinated people who still get sick, are hospitalized, or die from Covid-19.”

For Naughton and millions of other “essential workers,” laboring in the pandemic has been a mix of fear, insult and injury. Even when Covid-19 was at its most deadly and virulent, basic safety measures such as social distancing, mask-wearing and cleaning were “never enforced” at Walmart, says Naughton. “They never gave us any PPE, just glass cleaner, which doesn’t protect us. Customers could come in without masks and nothing would be said to them. I complained about it and the manager said, ‘Don’t worry about it, let the customers do what they want.’”

Several of Naughton’s coworkers got infected and ill from Covid-19, but “management never said a word to any of us,” he says. “Most of them I came into close contact with. That kind of scared me. … We all should have known about it.” Naughton says he filed a complaint in November 2020 requesting OSHA to inspect the Baton Rouge Walmart, but “I never heard back, nothing ever happened.”

To top it off, when Naughton received the vaccine in May, he was hit by a 102.4 degree fever — but he had to work anyway, because Walmart employees can “lose our job” after five absences for any reason. Nobody at Walmart took his temperature or inquired about his health, he says.

Through email, Tyler Thomason, Walmart’s senior manager of global communications, insisted to In These Times, “We encourage our associates to get vaccinated. We offer the vaccine at no cost to associates… We continue to request that associates and customers wear face coverings unless they are vaccinated. Any information on confirmed, positive COVID-19 cases would come from the local health authority.”

Unions Sue to Protect More Workers

Naughton isn’t the only person disappointed by Biden’s exclusion of most workers from this emergency pandemic protection. Unions have pushed for the protection since the pandemic began ravaging the United States in March 2020. First, they encountered staunch resistance from the Trump administration; now, while pledging expansive worker protections, the Biden administration has delayed and diminished them.

On June 10, as the Biden administration announced the narrow new rule leaving out millions of workers, advocates expressed disappointment and frustration.

Biden’s decision to cover only health care workers “represents a broken promise to the millions of American workers in grocery stores and meatpacking plants who have gotten sick and died on the frontlines of this pandemic,” stated United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) International Union International President Marc Perrone the day the new rule was announced.

That day, the AFL-CIO added, “we are deeply concerned that the [standard] will not cover workers in other industries, including those in meatpacking, grocery, transportation and corrections, who have suffered high rates of Covid-19 infections and death. Many of these are low-wage workers of color who have been disproportionately impacted by Covid-19 exposures and infections.”

On June 24, the AFL-CIO and UFCW filed a petition in federal court demanding that all workers be covered by the emergency standard, which, the petition says, currently “fails to protect employees outside the healthcare industry who face a similar grave danger from occupational exposure to Covid-19.”

Another champion of the emergency standard, Rep. Bobby Scott (D‑Va.), Chair of the House Committee on Education and Labor, also expressed frustration when Biden released the narrow new rule, calling the diminished standard “too little, too late for countless workers and families across the country,” including workers throughout the food industry and homeless shelters. Rep. Scott added: “I am disappointed by both the timing and the scope of this workplace safety standard.” The rule, Scott said, “is long past due, and it provides no meaningful protection to many workers who remain at high risk of serious illness from Covid-19.”

Biden’s decision to exclude meatpackers, grocery and farm workers, retail and warehouse laborers and others means especially high risks for workers of color, Rep. Scott noted. “With vaccination rates for Black and Brown people lagging far behind the overall population, the lack of a comprehensive workplace safety standard and the rapid reopening of the economy is a dangerous combination,” he said.

Much of this “essential” workforce of people of color, immigrants and low-income white people, toils in dangerous farm labor and food processing plants where Covid-19 has spread like wildfire while vaccination rates remain low. “Workers in this industry have a very low vaccination rate,” as low as 37% in some states, says Martin Rosas, president of UFCW Local 2 representing meatpacking and food processing workers in Kansas, Oklahoma and Missouri. “I don’t know who in their right mind would think we’ve passed over that bridge and think all workers are safe now.” Rosas adds, “The federal government has failed to protect meatpacking workers” by leaving them out of the final emergency standard. “I’m extremely disappointed in the Biden administration.”

Both the Department of Labor and the White House declined multiple interview requests, but a Department of Labor spokesperson emailed a statement insisting that the health-care-workers-only rule “closely follows the CDC’s guidance for health care workers and the science, which tells us that those who come into regular contact with people either suspected of having or being treated for Covid-19, are most at risk.”

The Department of Labor spokesperson stressed that the agency’s existing (yet unenforceable) “guidance” and the “general duty clause” protect other workers adequately, particularly in “industries noted for prolonged close-contacts like meat processing, manufacturing, seafood processing, and grocery and high-volume retail.” But in its own draft standard, the Department of Labor stated the opposite: “existing standards, regulations, and the OSH Act’s General Duty Clause are wholly inadequate to address the Covid-19 hazard.” In its original draft, the agency insisted, “a Covid-19 ETS [emergency temporary standard] is necessary to address these inadequacies.”

Marcy Goldstein-Gelb, National COSH’s co-executive director, says President Biden “is responsible” for the 15,000 workers who have died from Covid-19 since Biden’s March 15 deadline to enact the emergency standard. Biden, she notes, “promised to protect workers in his campaign and on his first day in office, but he neglected them. But workers’ safety needs aren’t over, and we’ll be continuing to demand accountability from the administration.”

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.