This story is part of the series Getting to Zero: Decarbonizing Cascadia, which explores the path to low-carbon energy for British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. This project is produced in partnership with InvestigateWest and other media outlets.

Worried about the climate crisis? You’ve got plenty of company after the events of 2021: Heat waves, hurricanes, fires, and floods hit new and deadly extremes. Global leaders belly-flopped well short of the pool at a pivotal climate-protection summit, even after the United Nations declared a “code-red” emergency.

And, in the United States, political gridlock chopped the heart out of Congress’ most ambitious clean energy plan.

Meanwhile, across the dewy-green region north of California, supposedly eco-friendly governments of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia that failed to fulfill climate promises for a decade have once again pledged to do better. But planet-warming emissions just keep on increasing, according to analysis of the latest data by InvestigateWest for the series “Getting to Zero: Decarbonizing Cascadia.”

And yet there is hope. The climate news coming out of British Columbia and the U.S. Pacific Northwest – “Cascadia” to many – is decidedly positive in three important ways, as the yearlong Getting To Zero series demonstrated:

- Cascadia has in its possession or within its reach all the technological firepower needed to go carbon-neutral by midcentury. If not sooner.

- The economics of carbon-free living have fallen into place. Renewable solar and wind power now typically costs less than fossil-fuel alternatives. This is also largely true across North America, and beyond.

- In British Columbia, Premier John Horgan’s government detailed policies to nearly double climate-protection efforts. And the Oregon and Washington legislatures passed their most concrete plans to date to rein in climate-wrecking greenhouse gases.

“This legislative session seems like a new beginning,” said Darcy Nonemacher, lobbyist for the Washington Environmental Council, a coalition of the state’s biggest environmental groups.

None of that ensures that the region known for its pro-environment leanings will actually get the job done. All three governments have failed to meet previous promises. Much work remains.

And yet, “This region still has an extraordinary opportunity,” said KC Golden, a longtime Seattle-based climate campaigner and board director at international climate group 350.org. “Day by day, we keep making progress.”

The lessons emerging here can translate to other regions. Reporters for InvestigateWest and news partners Grist, Crosscut, The Tyee, Jefferson Public Radio, and the South Seattle Emerald interviewed more than 200 people, including energy and policy experts, utilities officials, economists, community, labor activists, environmentalists, tribal officials, fossil fuel lobbyists, and more.

The journalists sussed out what it will take for the region to transition to a fully climate-friendly economy. It turns out that — viewed through that lens — the news is pretty encouraging. Here are the takeaway messages about what’s available and required to carry out the energy transformation:

Generate lots of clean energy

Yes, this first item on the list seems like a no-brainer. But it’s the key to the transition scientists say is necessary to keep the climate disruption humanity is experiencing today from becoming tomorrow’s climate catastrophe — a future in which civilization is upended by refugees, food and water shortages, deadly heat waves, and worse.

Arresting climate change means ratcheting down greenhouse gas emissions steeply over the next eight years. That’s looking more doable as renewable-energy prices drop, providing an alternative to fossil fuels. Over the last decade, solar costs fell more than 80 percent, and wind costs are quickly declining as well.

Jeffrey Sachs, an economist at Columbia University, said leaving behind fossil fuels is “feasible, necessary … and not very expensive” when compared to the overall economy.

Sachs’ view was backed in a July 2021 study from the San Francisco-based think tank Energy Innovation, which pulled together eight research efforts by universities and other experts. They concluded that the transition:

- Will have marginal costs.

- Is bound to create jobs.

- Will improve public health.

- Is challenging but feasible.

- Would make electricity more dependable.

Use that green energy to electrify everything possible

Once the juice flowing through the lines is green, we need to use it as widely as possible.

This starts with cars and trucks. Here again, the news is good. Electric vehicles are making huge inroads in the market. The infrastructure bill passed by the U.S. Congress last month allocates $7.5 billion to help build out a nationwide network of EV charging stations. The current 50,000 or so stations are to be expanded to 10 times that by 2030.

The second most important target for green power is replacing fossil fuel use in buildings, especially growing use of natural gas for heating; in Vancouver, British Columbia, that causes nearly 60% of the city’s carbon pollution.

Electric heat pumps can replace furnaces and, despite their name, they can actually heat and cool. That’s one reason why heat pumps seem destined to follow electric vehicles in popularity, said Merran Smith, executive director of Vancouver-based nonprofit Clean Energy Canada. “Heat pumps used to be big huge noisy things,” Smith said. “Now they’re a fraction of the size; they’re quiet and efficient.”

Combined with other innovative devices such as electric induction cooktops, heat pumps mean we can completely stop feeding so-called “natural” gas to buildings. And that’s crucial.

Natural gas made sense as a “bridge” to a carbon-free future back when environmentalists began promoting it as an alternative to dirtier coal and petroleum two decades ago. But now that bridge has grown too long and too wide.

Thanks to “fracking” technology that made natural gas cheap and abundant, its consumption went wild, along with methane leaks from gas pipes that further plague the climate. Given the imperative to cut carbon wherever possible, it’s time to start closing lanes on the natural-gas bridge.

That’s begun in Cascadia. Seattle this year passed a law to phase out natural gas in new commercial establishments and large apartment buildings. And in Vancouver, British Columbia, the City Council is requiring zero-emission space and water heating in all low-rise residential buildings constructed after this year.

Clean up what you can’t plug in

The biggest challenge beyond electrifying buildings and reining in natural gas is figuring out how to refuel gasoline- and diesel-powered trucks, ferries, buses, and trains, and airplanes. This one is going to be hard, especially for the biggest vehicles.

“The scale of this is huge,” said John Holladay, who directs transportation fuels research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington. “It’s a very aggressive scenario.”

The key will be making low-carbon fuels without creating new problems. Right now a smidgen of cleaner fuel is produced from plant and animal waste. But that’s a limited source. As such

“biofuels” scale up, producers will shift to using wood harvested from forests and oils produced from crops. That could boost food prices, cause ecological harm and even increase carbon emissions if not carefully monitored.

Going further is going to require new fuels that are still being perfected, such as hydrogen and low-carbon “synthetic” fuels — clean energy carriers that are gaining ground overseas but aren’t a big factor yet in the U.S. and Canada.

Invest in the grid

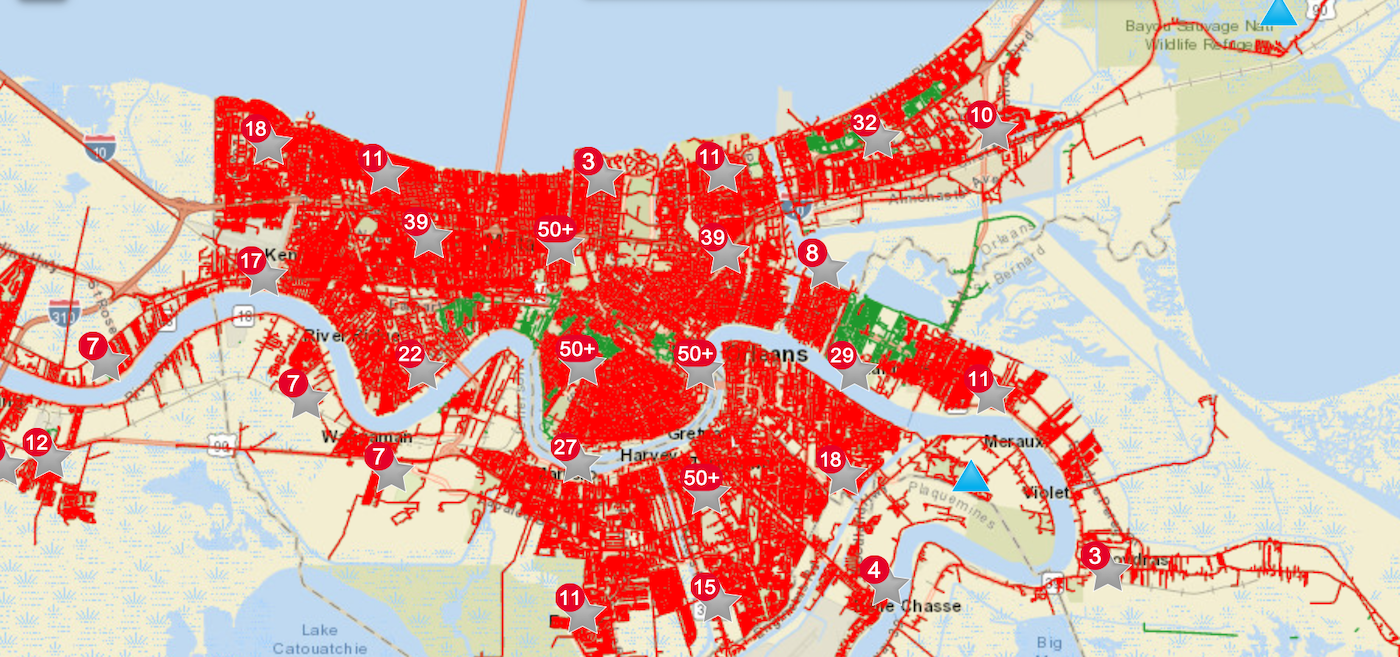

Beefing up the electrical grid is a precondition for any carbon-free electricity solution, worldwide. Additional lines are needed to connect a lot more wind and solar plants, and even more capacity is needed to deliver their power.

A spring 2019 cold spell vividly illustrated this need for Cascadia. The fall 2018 rains had faltered, leaving reservoirs low behind dams that produce hydroelectricity, the region’s go-to, low-carbon energy source. Being connected to a grid whose 136,000 miles of transmission lines span all of Canada and the U.S. west of the Rockies would usually provide some backup. But in this case work on power lines in Southern California and mechanical problems at the Centralia, Washington coal-fired power plant left power supplies short.

Cascadia came close to experiencing the rolling blackouts that have since disrupted California and Texas.

“We really had a very close call,” said Scott Bolton, senior vice president for transmission development at Portland-based PacifiCorp.

Investing in a more robust grid may sound mundane, but it’s vital to how a primarily renewable energy system of the future can work. When the wind is blowing in, say, Montana, long transmission lines mean people in Portland can still cook their dinner and heat their homes even if overcast skies are sapping output from their rooftop solar panels. And if the wind fails in Montana, it’s a good bet that solar, wind and/or water power dispatched from Cascadia could help save their day.

This opportunity to trade energy for mutual advantage stretches far beyond Cascadia. Alas, three major electrical grids serve Canada and the U.S., and very little power can actually be shared even within the Western grid. Solving that problem and in general rebuilding a sturdier grid could go a long way toward helping both Canada and the U.S. move toward a carbon-free energy future.

Give consumers more power

Energy planners increasingly are recognizing the value of consumers generating at least some of their own power. This currently is mostly achieved through rooftop solar and is increasingly augmented with big batteries.

If consumers install batteries, excess power generated when the wind is blowing and the sun is out can be stored for use at night, during dark days or when wind dwindles. Costs for batteries are declining steadily, and especially steep cost cuts are projected for the next few years.

An important study released in February found that coordinating big grid upgrades with consumer-scale solutions could translate into the U.S. hitting its clean-energy goals while also saving consumers more than $470 billion, mostly between 2030 and 2050.

New technologies coming online are helping to smooth the coordination challenge, preventing power glitches when consumers saturate the local lines with solar energy. Other equipment is helping prevent blackouts by moderating consumption from “smart” appliances when the grid’s appetite for power is surging.

Promote new technologies like hydrogen

Meanwhile, research and development continues to examine additional ways to produce green energy. One of the most promising is “green hydrogen.”

Here’s how this works: Pretty much anywhere there is cheap or excess power – in Cascadia the classic example is hydropower when the spring snowmelt goes bonkers – a device called an electrolyzer can use that electricity to split water into hydrogen, a combustible fuel, and oxygen.

As wind and solar energy soars, hydrogen, or liquid fuels made from it could be used to replace fossil fuels for heavy vehicles, as well as industries that are difficult to plug into the grid.

In addition, the green hydrogen can be stored in bulk, providing reserves of climate-friendly energy to generate electricity during extended dark and windless periods. It would make the power system far more resilient and less subject to nature’s whims.

Political will

“Political will” is the shorthand used by environmentalists for what they say society needs from politicians: leadership to rejigger our fossil-fueled economy in spite of attacks from political opponents and powerful interests such as oil companies and utilities.

“The constraining factor has always been political feasibility, not economic feasibility,” said Mark Jaccard, a political economist and energy modeling expert at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia.

One could scarcely ask for a better example of how this plays out in the real world than Washington Gov. Jay Inslee. The governor based his 2020 presidential run almost entirely on his convictions about fighting climate change. Yet under Inslee’s watch, Washington has allowed expansion of highways, gas-fired power plants and a new terminal for liquefied natural gas, among other actions that increased climate pollution.

It’s that day-in, day-out work that government traditionally has done. And it inspired lawsuits from youth in Washington and Oregon.

“Washington has been defending itself by saying, ‘We have been doing the best we can. We have got Inslee. Look at the progress,’” said attorney Andrea Rodgers, who represents the eight young people who sued in Washington. “But emissions don’t lie, and the emissions keep rising.”

The plaintiffs in Oregon and Washington lost their final appeals last year and in October, respectively. But youth in the U.S. and Canada continue to push a pair of related challenges against their federal governments.

The list of well-heeled interests lobbying against a fast transition to clean power — the one scientists say is needed to avert climate disaster — is long. The ones that present the greatest roadblock for the energy transition are natural gas companies and unions representing trades such as pipefitting, which continue fighting efforts to fully electrify buildings and phase out gas. Gas firms and labor unions are pulling out the stops politically by financing candidates, running pro-gas advertising campaigns and even, in some cases, hiring actors to pose as concerned citizens at public hearings.

In short, changing the energy system is going to involve economic losers and winners. Politicians have to stand strong and follow through on policies that make sense for society as a whole, and for future generations.

Jobs, jobs, jobs

While much of this list focuses on items that may initially cost consumers and businesses more, it’s important to remember that an out-of-control climate is expected to wreak much more costly havoc. It’s also important to factor in how employment can transition along with energy. As job losses occurred at, say, the coal-burning Centralia power plant, other jobs are being created at wind and solar energy sites, factories for electric semi-trucks and buses, and beyond.

One study projected more than 60,000 additional jobs could be produced in Washington with an ambitious plan to replace old and inefficient equipment and construction of renewable power plants. Compared to Washington’s 3.6 million current jobs, that is not huge. But it represents a net increase in employment.

People power

To ensure that politicians stand strong and build the future, citizen-activists say they must keep pressure on the politicians and spotlight backsliding. Environmentalists and community activists in Cascadia and California surprised even themselves with their success in a decade-long campaign that blocked dozens of proposals to export fossil fuel from the U.S. interior across the West Coast to Asia, as one Getting To Zero story explored.

Now, the struggle is much broader and affects vast areas of the entrenched economic system. Another story in the series reported on recent successes by citizen activists at the local level who have lobbied for outright bans on a range of fossil fuel handling facilities, from refineries to airports.

Even though the climate-action movement is making progress, those who’ve witnessed its history say continued pressure will be key to driving an energy transition. The news here, too, is good.

“Concern and a sense of urgency are way up,” said longtime Seattle climate activist Patrick Mazza. “The climate movement is in the streets, with broad and inclusive engagement. Such a contrast with the early days!”

Listening to and protecting traditionally marginalized communities

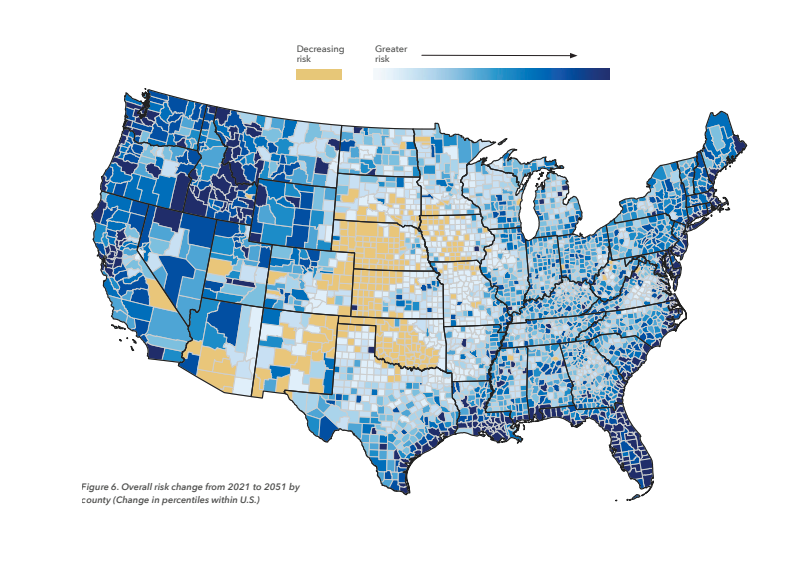

When Mazza mentions “inclusive engagement,” part of what he is talking about is growing involvement of people of color and sovereign Tribes and First Nations in the climate movement. That’s essential, not least because climate disruption poses a disproportionate threat to people in traditionally marginalized communities, as an early Getting To Zero story explored.

Planning for a climate-hammered future involves looking not simply at which communities are most threatened by floods, fires, and heat waves, but also at which communities are the least prepared to deal with disaster because of their socioeconomic makeup. People who are scraping by economically are unlikely to have the money they need to install a fireproof roof, for example, or to rebuild after flooding destroys their town.

Going forward with a clean-energy transformation also means taking explicit steps to ensure that people at the bottom end of the economic spectrum are protected economically.

For example, a Getting To Zero story about retrofitting buildings highlighted the Ramos family of Portland, who saw punishing air-conditioning and heating bills ease after installation of a low-energy “heat pump” at public expense. The nonprofit Energy Trust of Oregon shelled out money to better insulate the Ramos’ house as well.

Bringing real-dollar help to those on the lower end of Cascadia’s socioeconomic spectrum will be important, say those researching how to speed the transition to a climate-friendly economy.

“The heat pump system works like a charm,” said Francisco Ramos. “I can’t express enough what a big difference this system made in my life.”

Heal the land, heal the climate

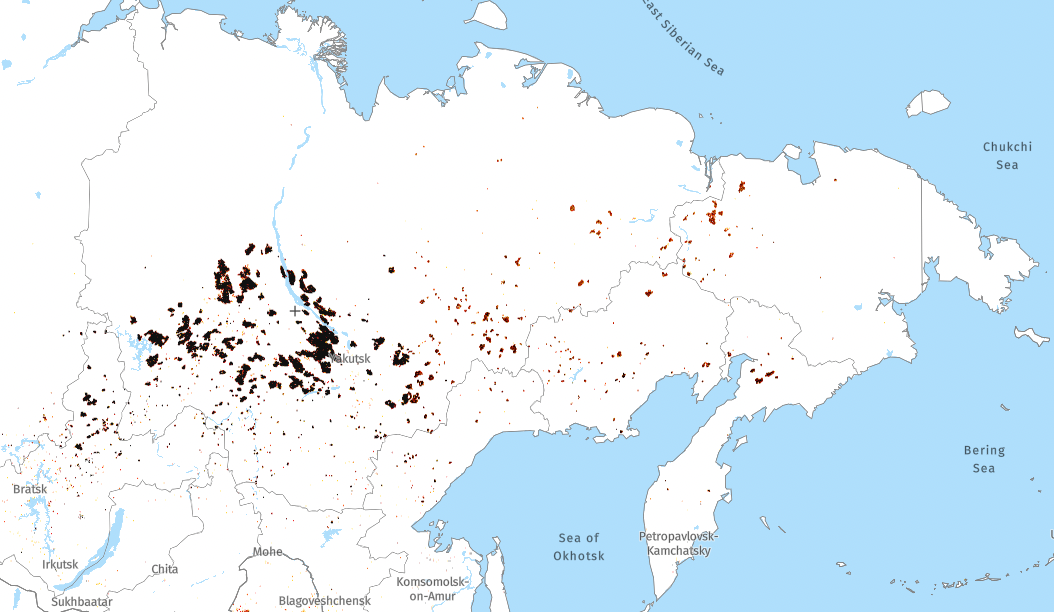

One of the most important and yet under-the-radar requirements to reduce Cascadia’s planet-warming emissions is rethinking how we are managing the region’s once-abundant forests.

On the way to the current climate reckoning, an interesting thing happened to the region’s forests: They’ve been transforming from green swaths of landscape, which reliably helped suck up airborne carbon since the Industrial Revolution, into sources of the most prolific greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide.

This happened in part because of a century-plus-old policy of extinguishing every forest fire possible. The legacy of putting out forest fires: lots of small shrubs and trees that in centuries past would have been regularly cleared out by fires. Instead they now crowd forests that are tinder dry thanks to hotter, drier weather wrought by climate change. The result is the unnatural “mega-fires” that blanket the Cascadia region in smoke most every year, send residents fleeing or to hospital, decimate tourist economies, and pump millions of tons of carbon dioxide skyward.

The most basic solution? Adapt forestry practices for the climate-altered world we live in. Thin forests rather than clearcut. Harvest less often to allow trees to soak up more carbon. And plant trees, a lot of trees — as long as they’re adapted to their location.

“There are no foolproof solutions,” said Natasha Kuperman of Seed the North, whose silviculture experiments in northern British Columbia were profiled in one story. “This is harm reduction. This is mitigation. And that is the best thing that we can do with our lives.”

Can Cascadia carry through?

This part of the world has inherent advantages in its bid to go completely carbon-neutral, including a moderate climate, an increasingly progressive electorate and the massive amount of low-carbon energy generated from its dammed rivers.

Certainly more could and should be done, environmental campaigner Golden says.

He quotes the groundbreaking economist John Maynard Keynes, who observed, “The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.”

Breaking through long-standing patterns of economic development, long spurred by that network of power-producing dams, represents an extraordinary opportunity, he says. Even more needs to be done to make that system work in tandem with all the other clean-energy sources coming on line and thus to show the rest of the world how to do this, he said.

“This region’s got an awful lot going for it,” Golden said. But, he added, “I still don’t think we’re using all our advantages to our maximum potential.”

With reporting from Iris Crawford, Andrew Engelson, Michelle Gamage, Lizz Giordano, Mandy Godwin, Amanda Follett Hosgood, Ysabelle Kempe, Braela Kwan, Erik Neumann, Shannon Osaka, Levi Pulkkinen and Jack Russillo.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Lessons from a year of reporting on climate solutions in Cascadia on Dec 15, 2021.

This post was originally published on Grist.