Trump’s immigration crackdown could cause chaos for communities trying to rebuild after devastating wildfires and floods, as the vast majority of skilled disaster-restoration workers are immigrants, a leading expert has warned.

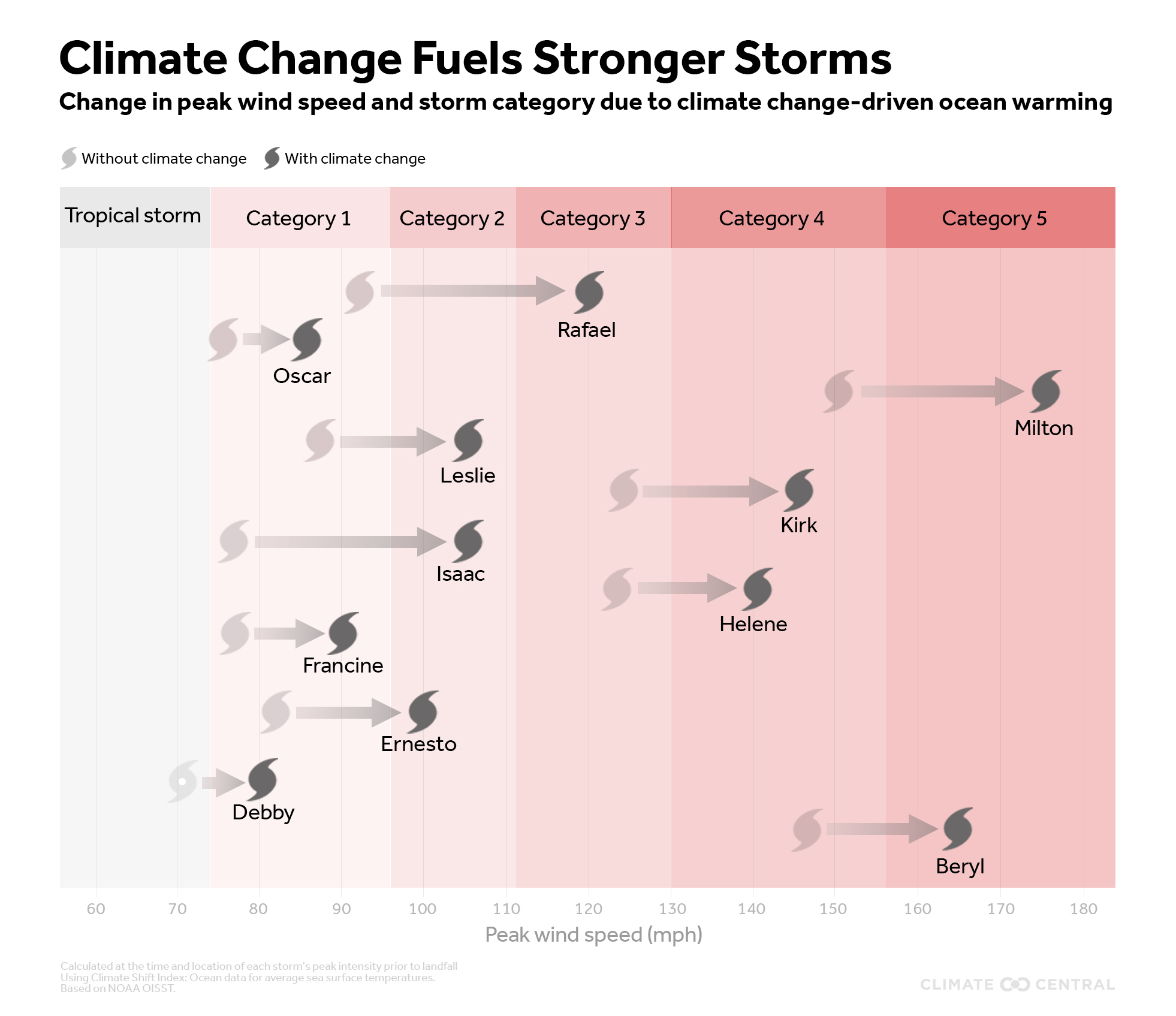

Republican and Democratic voters across the US are reeling from climate-fueled disasters, with thousands of homes and businesses destroyed and damaged by the ongoing fires in Los Angeles, as well as major hurricanes in Florida, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia last year.

In each place, recovery depends on restoration or resilience workers, who travel from disaster to disaster cleaning up and rebuilding American communities while facing hazards such as unstable buildings, ash and other toxins, and water-borne diseases.

“Like farm workers in the fields, immigrants are indispensable to fire, flood, and hurricane recovery in the US. There is absolutely no rebuilding without them,” said Saket Soni, director of Resilience Force, a labor organization with almost 4,000 members, who are primarily immigrant workers.

“Mass deportations would completely upend the ongoing recovery in Florida, Louisiana, and North Carolina from last year’s hurricanes. It would stall the rebuilding of LA after fires … and at this point, anyone anywhere is at risk of having their home impacted by a climate disaster. So everyone need these skilled workers.”

The disaster industry is growing in the US, as climate-fueled extreme weather events become more intense and destructive – and as rebuilding becomes more profitable.

While there is no official count, the current resilience workforce includes tens of thousands of mostly foreign-born workers from across Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as India and the Philippines, among other countries. It is a diverse mix of skilled workers that includes undocumented immigrants, as well as many documented asylum seekers, settled refugees and those with work permits through temporary protected status (TPS).

Trump’s flurry of executive orders and policy ambitions threaten to upend the entire immigration and asylum system. Expanding workplace raids and mass deportations may temporarily satisfy Trump’s anti-immigrant base, but the knock on labor shortages will likely be felt across multiple sectors including construction, food, hospitality, and disaster work.

“The deportations plan is so out of touch with the reality of the victims, who without immigrants will continue to spend months, maybe years in hotels living out of pocket. Recovery often makes the poor even poorer and getting back into your home is the key safeguard against spiraling inequality,” said Soni, who has been involved in 25 disaster-recovery efforts over the past two decades.

“We’re headed for a moment where there’ll be a reckoning between such political ploys and reality. And at some point this will become a moral question rather than a political one.”

Among the biggest obstacles facing families after a destructive fire, tornado, or flood are labor shortages – and funding. Trump’s policy pledges will make both worse.

On Friday, Trump announced his desire to potentially shutter the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during a visit to North Carolina, where rural Republican-voting communities faced some of the worst damage from Hurricane Helene – one of the most destructive and deadly storms to hit the US mainland in years. Helene was among 27 separate billion-dollar disasters to hit the US in 2024.

The estimated cost of the damage in North Carolina from Helene, which hit six states across southern Appalachia all of which voted for Trump, is almost $60 billion. Here, four months after the floods, there is much work still to do – from debris removal and mold remediation to roof replacements and geological repairs to hillsides.

Also on Friday, Trump visited Los Angeles, where more than 11,000 homes have been destroyed and the damage caused by just two of the blazes – the Palisades and Eaton fires – is now estimated at $275 billion. At least 150,000 people have been displaced, and many have applied to FEMA for help. “You don’t need FEMA, you need a good state government, you fix it yourself,” said Trump, after touring some of the fire-ravaged area.

FEMA provides emergency assistance for temporary accommodation, food and unemployment benefits, as well as reimbursing individuals and states for clean-up and rebuilding costs, which are not covered by private insurance.

“Abolishing FEMA would invite a pretty major response over the next few years because no state will absorb that amount of responsibility or spending. The states would rise up – especially the very red states like Florida, Texas, and Louisiana that this administration counts on for its constituents and where disasters happen again and again,” said Soni.

“We will need FEMA to be bigger, not smaller. Any resident who’s been through a hurricane or wildfire, whether Democrat or Republican, will agree with that. Fires aren’t making a distinction between political parties. We have Republicans in California who need FEMA just as much as the Democrats.”

On Monday, it emerged that the Trump administration had issued new quotas to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to ramp up raids and arrests, the Washington Post reported.

The expansion of workplace raids could force some restoration workers underground – as happened in 2022 after Hurricane Idalia when Republican Florida Governor Ron DeSantis passed draconian anti-immigrant legislation. “Immigrant workers put their tools down and left in fear, leaving homes to be rebuilt and families in limbo. That was very bad for Floridians who were depending on those workers, but the workers needed to be careful,” said Soni, speaking from North Carolina where he was meeting homeowners desperate to repair and return to their homes.

“Even among those who are documented, many restoration workers have a tenuous foothold in America – people who are not yet citizens and are being threatened by Trump. People are scared, and yet these workers have a deep sense of vocation. There’s something sacred about working after a fire or a hurricane so that a family can come home. What is more important than that?”

The resilience workforce has grown massively since Katrina flattened New Orleans in 2005, after which the city was rebuilt by mostly undocumented Latino workers. Since then, the industry has consolidated, with private-equity firms buying up small businesses, with minimal protection for workers and little regulatory oversight.

The working and living conditions can be brutal for the immigrant workers, many of whom come from countries hit hard by the climate crisis caused by planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions – of which the US is the largest historic contributor.

“We have workers from Honduras who right now are rebuilding the homes of Floridians – and are in Florida because a hurricane destroyed their home and forced them to leave. Do you know how much grace it takes to replace someone else’s roof while your own home is uninhabitable? And yet the workers persevere with grace and persistence,” said Soni, author of The Great Escape: A True Story of Forced Labor and Immigrant Dreams in America, which chronicles the story of Indians lured to the US to help rebuild New Orleans.

“Volunteer efforts in Appalachia and Los Angeles have been extraordinary, but the truth is that the scale of damage we’re seeing across the US requires a skilled, scaled workforce. If you deport one generation of restoration workers, you can’t just add water and have another generation appear. It’s taken two decades to build the workforce that we have. And without them, everyone’s at risk.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘No rebuilding without them’: Trump’s immigration crackdown will affect disaster recovery on Feb 2, 2025.

This post was originally published on Grist.