Domonique Tomlinson didn’t know much about the Shore Acres neighborhood of St. Petersburg, Florida, when she bought a house here four years ago, but she learned fast. Just a few weeks after she moved into her single-story teal home, a high tide overwhelmed her street’s drainage system and pushed water into her house. The same thing happened again during Hurricane Idalia in 2023; she lost furniture and belongings worth thousands of dollars. Then there was just the everyday flooding to contend with. It happened more times than she could count, when she had to wade through calf-high water on her street to get to her teaching job, wiping herself with Lysol when she got to work.

Tomlinson and her husband were racing to install plywood flood panels and sandbags on Wednesday as Shore Acres prepared for a historic storm surge from Category 4 Hurricane Helene. As she loaded a Peloton into her car, she said she was fed up with flooding over and over again.

The following night, Helene delivered the largest storm surge on record to Shore Acres, pushing water not only into Tomlinson’s house, but into the houses of neighbors who had never flooded. Waiting out the storm on higher ground in downtown St. Petersburg, she kept up with reports from her neighbors who had stayed behind: The entire streetscape vanished as saltwater seeped in through sandbags and flood panels, filling up kitchens and living rooms.

“It’s just a really sad situation,” she told Grist. “We won’t rebuild, it’s not worth it.”

Even before Helene, Shore Acres looked like a casualty of sea level rise and faulty development. The waterfront neighborhood had begun to flood multiple times a month, even when it wasn’t raining, and residents were paying some of the highest flood insurance rates in the country, with the median annual premium in the neighborhood set to reach around $5,000. The city was racing to mitigate the flooding, but almost every street in the neighborhood had at least one “For Sale” or “For Rent” sign on it.

But Helene may turn out to be the neighborhood’s coup de grace: The hurricane pushed well over 6 feet of storm surge into Shore Acres on Thursday, the highest on record for the community. Based on early reports, the wall of water flooded hundreds of homes with 4 feet of water or more, dealing another hit to its already shaky real estate market. And as sea levels and flood insurance rates continue to rise throughout the eastern United States, from Florida to New England, Shore Acres may turn out to be not an outlier but a bellwether for future fragility in the real estate market and coastal economies more broadly.

Shore Acres is one of numerous areas in the coastal United States that were built for a different climate than that of today: The area expanded in the 1950s on what one developer called “a pretty sorry piece of land” made up of pine forest and marsh, and much of it sits just a few feet above sea level. The area has always seen occasional flooding during the highest tides, but now parts of it go underwater several times a year as autumn tides slosh over bulwarks and gurgle up through storm drains.

Even on sunny days, standing water is now a frequent occurrence in the neighborhood. When cars drive too fast through flooded streets, they create wakes that can splash up into driveways and damage other vehicles, or even rush into homes.

Tracy Stockwell, who moved to the neighborhood last year from Atlanta, has erected a series of signs and barriers in front of his house that read “Wake Stop” and “Slow Down, Watch Your Wake.” He said drivers have splashed through standing water multiple times and flooded his house — something he had no idea was possible when he bought it.

“The realtors did not disclose that,” he said, while preparing to ride out the storm on his second floor. “We knew that the street flooded, but we had no idea the history of the house.” Earlier this year, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, signed a law that required home sellers to disclose past flood insurance claims, but the law doesn’t go into effect until next month.

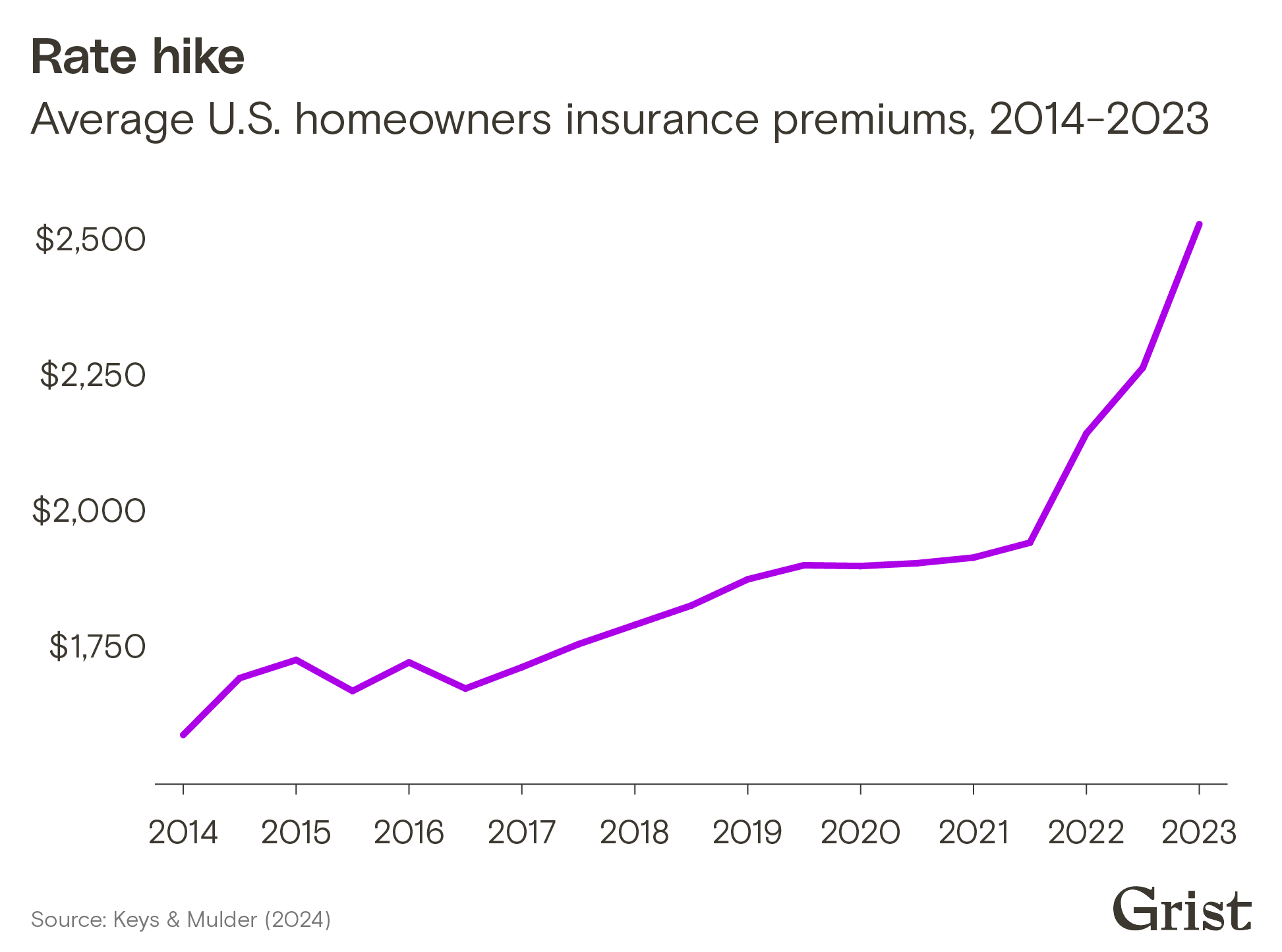

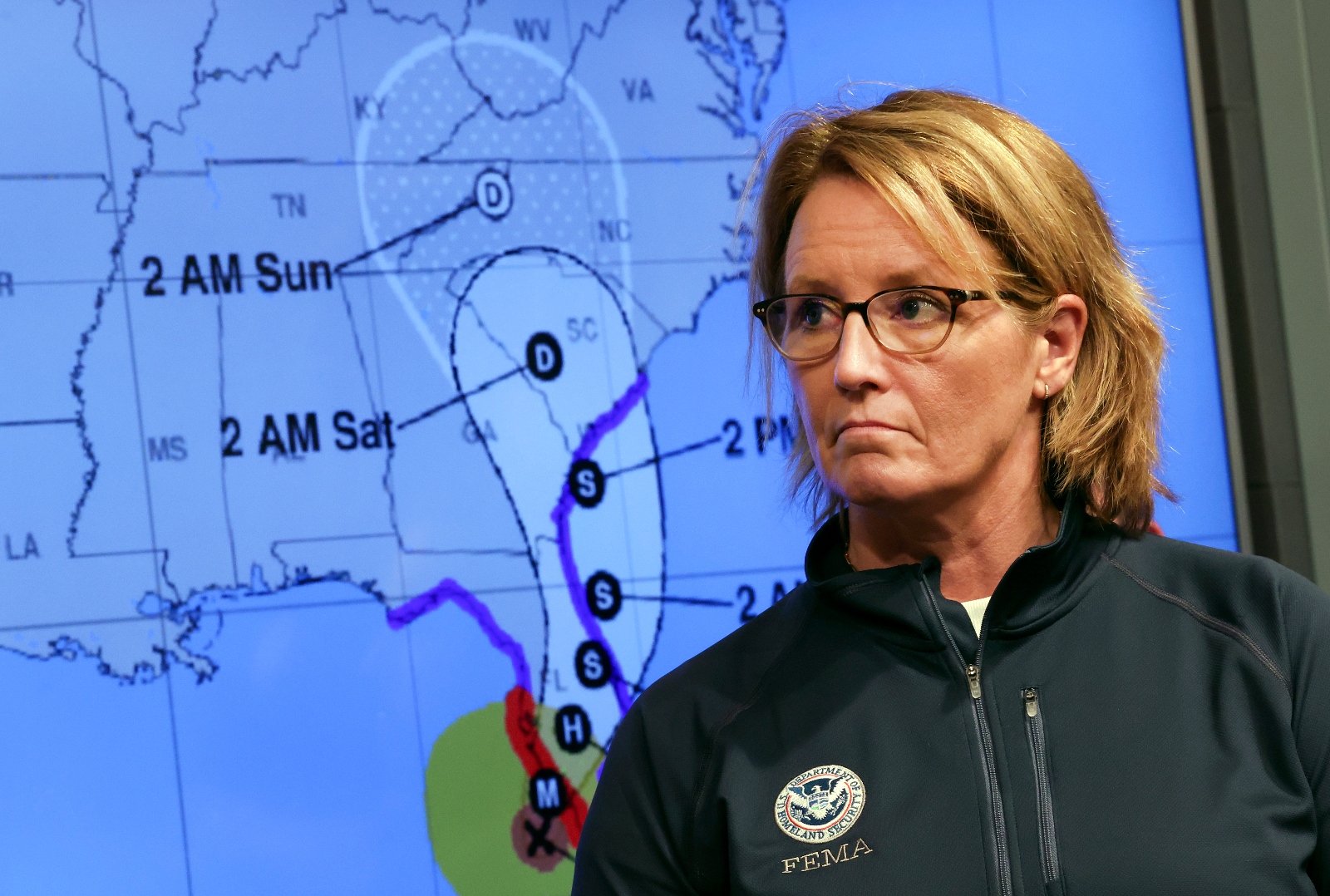

As the flooding in the neighborhood gets worse, residents have seen their flood insurance rates skyrocket under a new federal policy. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, which administers the national flood insurance program that serves around 5 million U.S. households, began to roll out this policy in 2022. The median cost of flood insurance in the neighborhood is around $2,000 per year, more than double the national rate, and may double again to around $5,000 as FEMA raises rates to phase in the new program. Many residents already pay far more than that.

Some neighbors have been able to save money on insurance costs by elevating their homes on stilts above flood level. Federal regulations require a homeowner to do this if their house suffers damage equivalent to more than half its value. But elevating a home requires a lengthy permitting process and can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars; moreover, FEMA’s new insurance pricing system offers a lower discount for doing this work than the old system did.

For people who can’t afford to elevate or can’t keep up with rising insurance rates, the only option is to leave, and as of Wednesday there were at least two dozen “For Sale” signs in the neighborhood.

Even so, some local boosters are projecting confidence in the real estate market.

“I think people understand now that flooding is going to occur,” said Kevin Batdorf, a real estate agent and the head of the Shore Acres Civic Association. “Flooding in Shore Acres is well known. It’s not something that is a secret. Some people have sold, and the houses are selling, because we live in a great neighborhood.” He went on to say that the neighborhood has seen small selloffs in the past after flood events, but that the market always calms down after a few months as new people move in.

But as Helene beared down, even those with deep connections to Shore Acres weren’t sure about their long-term future there. Tomlinson has said she won’t rebuild, and Stockwell said he planned to at least consider selling his home. They imagined their neighbors would be contemplating the same.

“That guy left, and that person left, and that person’s selling,” said David Witt, a furniture store manager, as he pointed at the houses on his street. He and his wife moved a few years ago into his wife’s childhood home, which is raised a few feet off the ground, and they’ve come within an inch of flooding several times. They are both attached to the home, Witt said as he lined his door with sandbags, but they aren’t sure if they want to stay for good.

There have been at least three other large floods in Shore Acres in the past 13 months, beginning with last year’s Hurricane Idalia and continuing this year with a no-name winter storm and Hurricane Debbie in August. The flood from Idalia damaged more than 1,200 homes in the neighborhood — close to half of all its structures. The neighborhood accounted for more than 80 percent of the damage St. Petersburg suffered during that storm. Helene traced a similar path to Idalia, scraping up the Gulf Coast and making landfall in the Florida Panhandle, but brought a storm surge several feet higher.

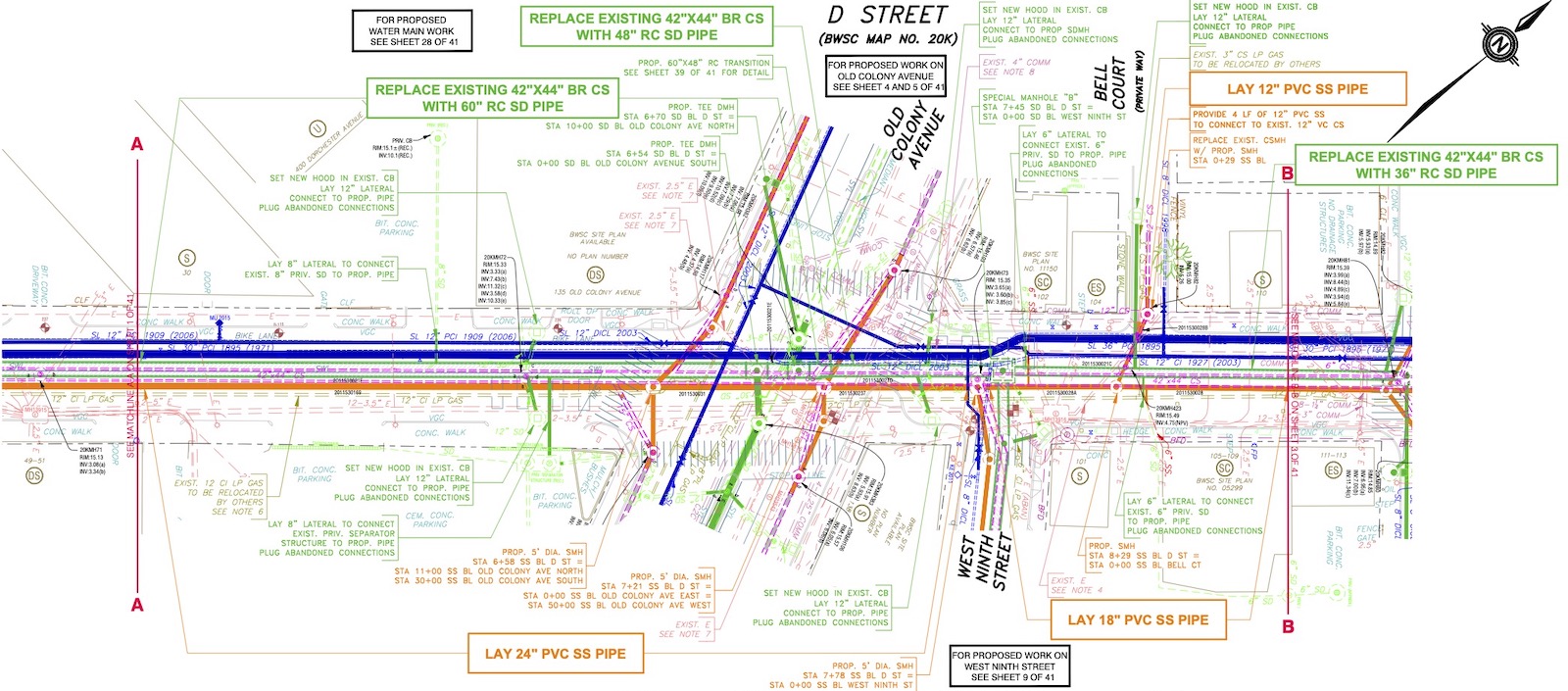

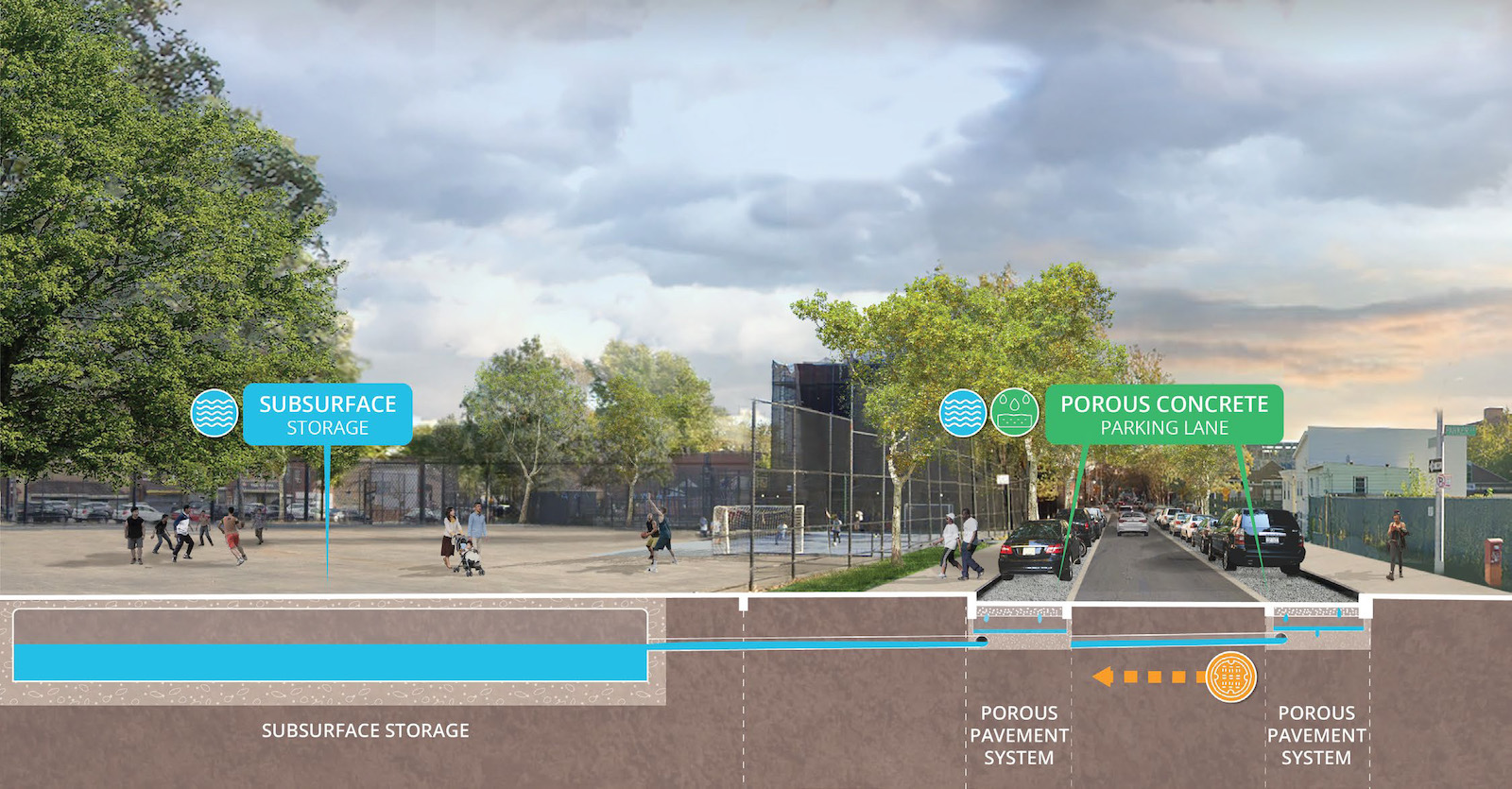

The city of St. Petersburg has invested millions of dollars over the past year to mitigate its flooding issue, installing backflow preventers that stop storm drains from overflowing onto streets when tides are high. It will soon begin construction on a $16 million pump station on the area’s lowest-lying street, Connecticut Avenue, replicating a strategy used in Miami Beach and New Orleans with money from the state government.

Batdorf, the civic association leader, said residents are working with the city to speed up these improvements and speed up grant programs that help residents elevate their homes.

“There’s so much more the city could do,” he said, “and there are other communities that have solved the issue of flooding.” He said that despite the city’s progress on installing backflow preventers, the sunny-day flooding issue hasn’t gotten better. Furthermore, there’s nothing the city of St. Petersburg could have done on its own to stop a storm the size of Helene. To mitigate such a surge would likely require a multibillion-dollar barrier of the kind the Army Corps of Engineers has contemplated building in Miami and New York City.

“They’ve always had flooding here,” Witt said, “but it’s never been this bad.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline This Florida neighborhood recovered from flood after flood. Will it survive Helene? on Sep 27, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.