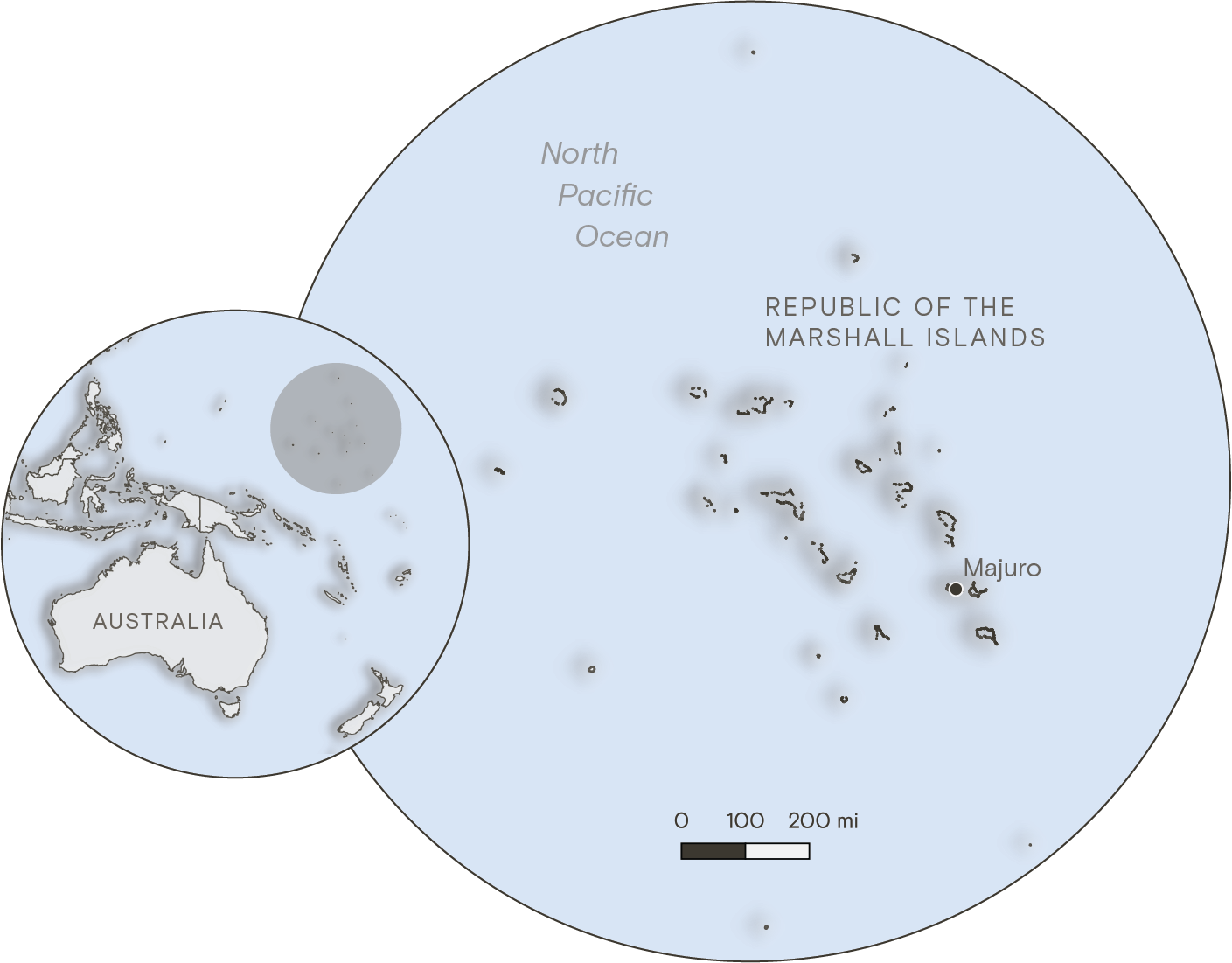

The Marshall Islands extend across a wide stretch of the Pacific Ocean, with dozens of coral atolls sitting just a few feet above sea level. The smallest of the islands are just a few hundred feet wide, barely large enough for a road or a row of houses. The country’s total landmass makes up an area smaller than the city of Baltimore, but it occupies an ocean territory almost the size of Mexico.

Over the past two years, government officials have fanned out across the country, visiting remote towns and villages as well as urban centers like its capital of Majuro to examine how Marshallese communities are experiencing and coping with climate change. They found that a combination of rapid sea-level rise and drought has already made life untenable for many of the country’s 42,000 residents, especially on outlying atolls where communities rely on rainwater and vanishing land for subsistence.

The survey was part of a groundbreaking, five-year effort by the Marshall Islands to craft a sweeping adaptation strategy that charts the country’s response to the threat of climate change. The plan, shared with Grist ahead of its release at COP28 in Dubai, calls for tens of billions of dollars of new spending to fortify low-lying islands and secure water supplies. Representatives from the Marshall Islands say the plan shows that their country can remain livable well into the next century — but only if developed countries are willing to help. Even with aid, the plan concedes many Marshallese will likely need to migrate away from their home islands, or even leave the country altogether for the United States, as climate impacts worsen.

“We call it our national adaptation plan, but it is really our survival plan,” said John Silk, the foreign minister of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, during a closed-doors panel conversation at the Clinton Global Initiative summit in New York in September.

Other vulnerable countries have submitted adaptation plans to the United Nations before, and some have even planned large-scale relocations to escape sea-level rise, but the Marshall Islands plan is different, and not only because of the existential nature of climate risk in the country. As they developed the plan, government officials interviewed more than 3 percent of the country’s population — some 1,362 people — during 123 days of site visits on two dozen islands and atolls. The only other national adaptation plan that has involved any community participation was that of the island nation of St. Lucia, in the Caribbean. In that case, officials interviewed only 100 people.

“We’re about to make a huge change to our islands, and we can’t do that if we just make that decision unilaterally as government representatives,” said Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner, a poet and activist who serves as the Marshall Islands’ climate envoy, in an exclusive interview with Grist ahead of the plan’s release. “It has to come from the community themselves too, because they’re the ones getting impacted.”

Experts who reviewed the plan described it as among the most comprehensive attempts by any country to plan for long-term climate impacts.

“This is one of the most thoughtful and meticulous long-term adaptation plans I’ve seen,” said Michael Gerrard, a law professor at Columbia University who has studied climate adaptation policy, including the Marshall Islands. “The plan doesn’t just wring hands; it sets forth a systematic decision-making process.”

Almost half of the Marshall Island residents interviewed for the plan said they’d witnessed sea-level rise in their communities, and nearly a quarter said they’d experienced a water shortage. More than 1 in 5 said climate change had threatened food security for their households.

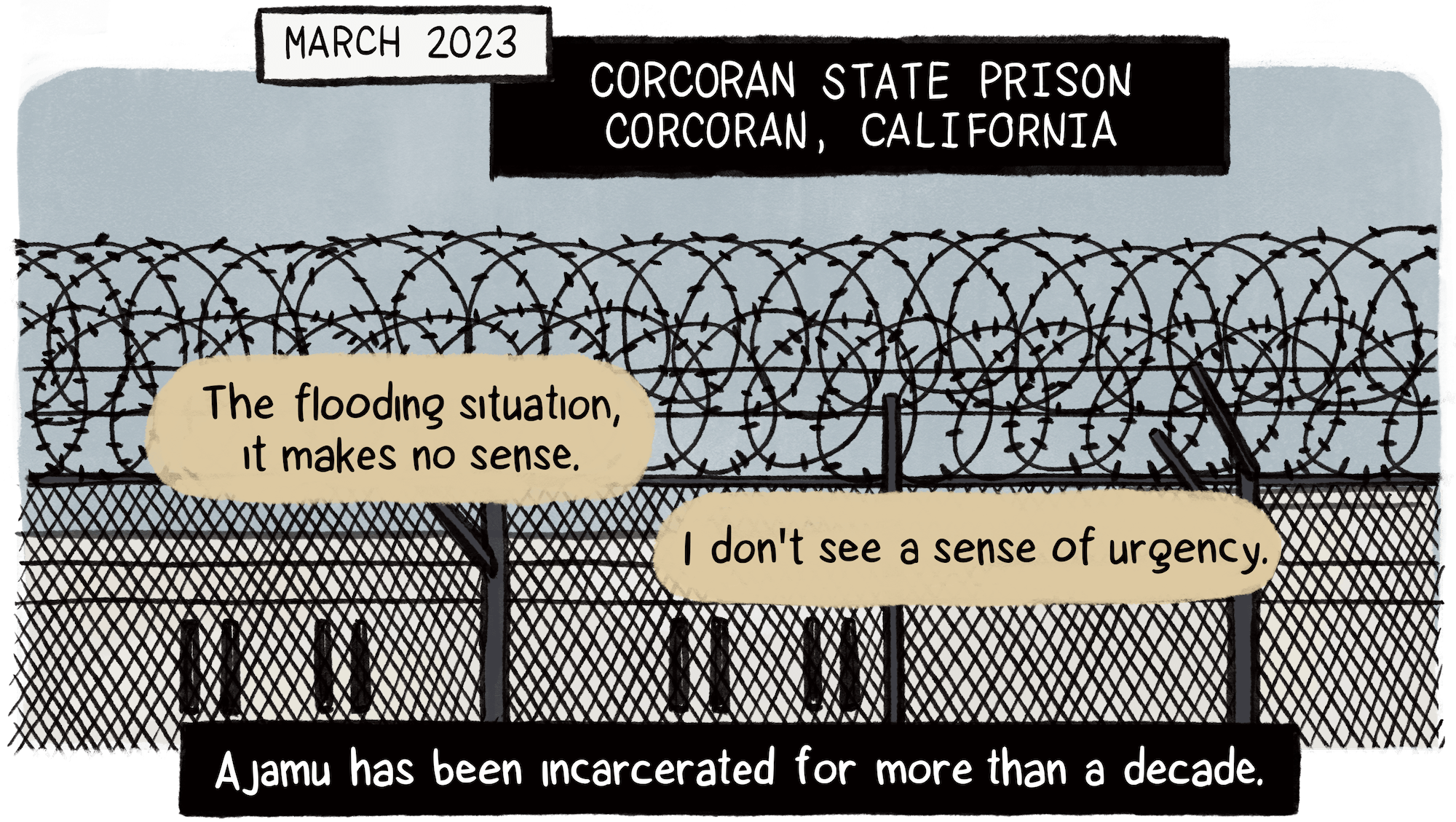

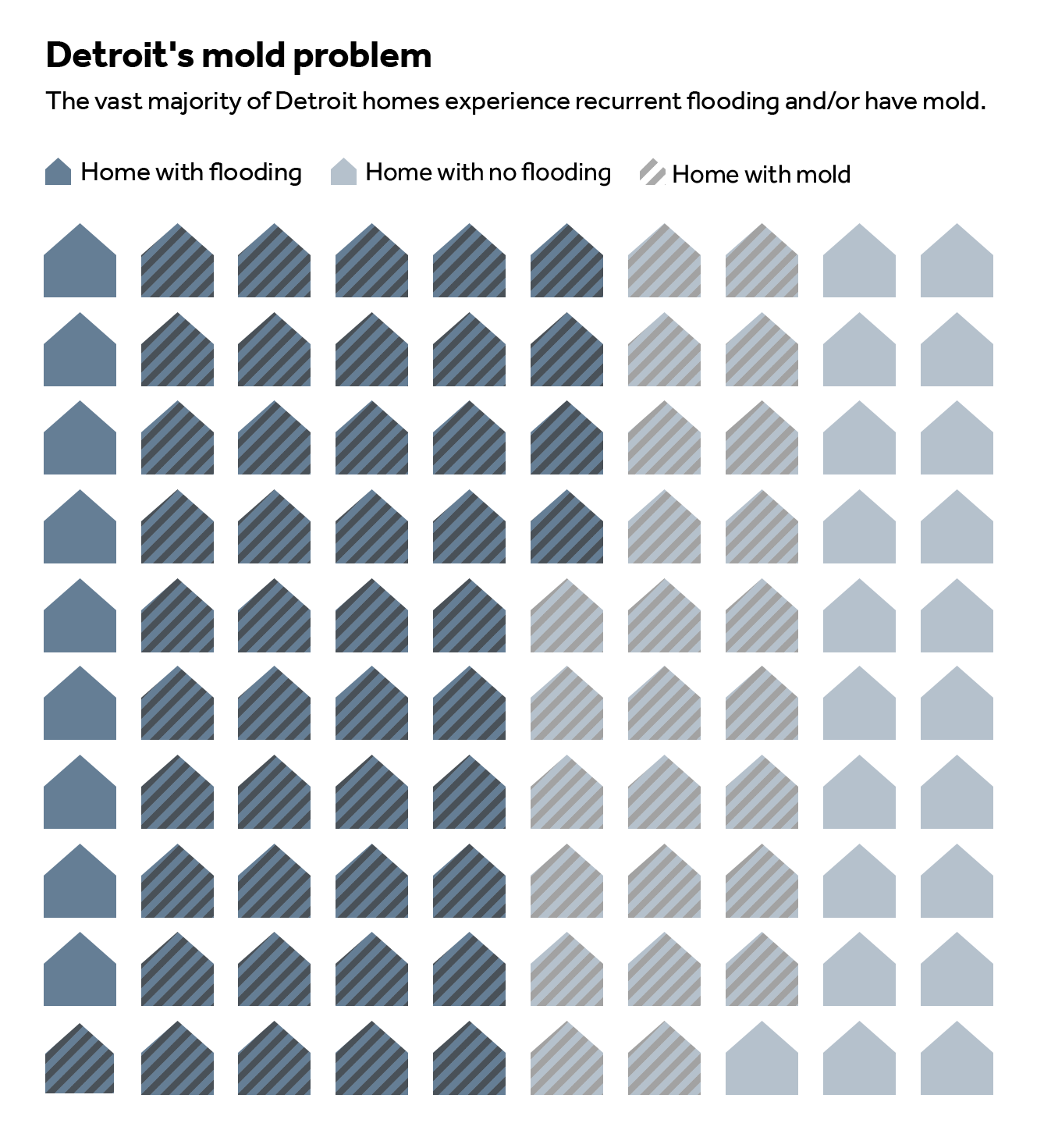

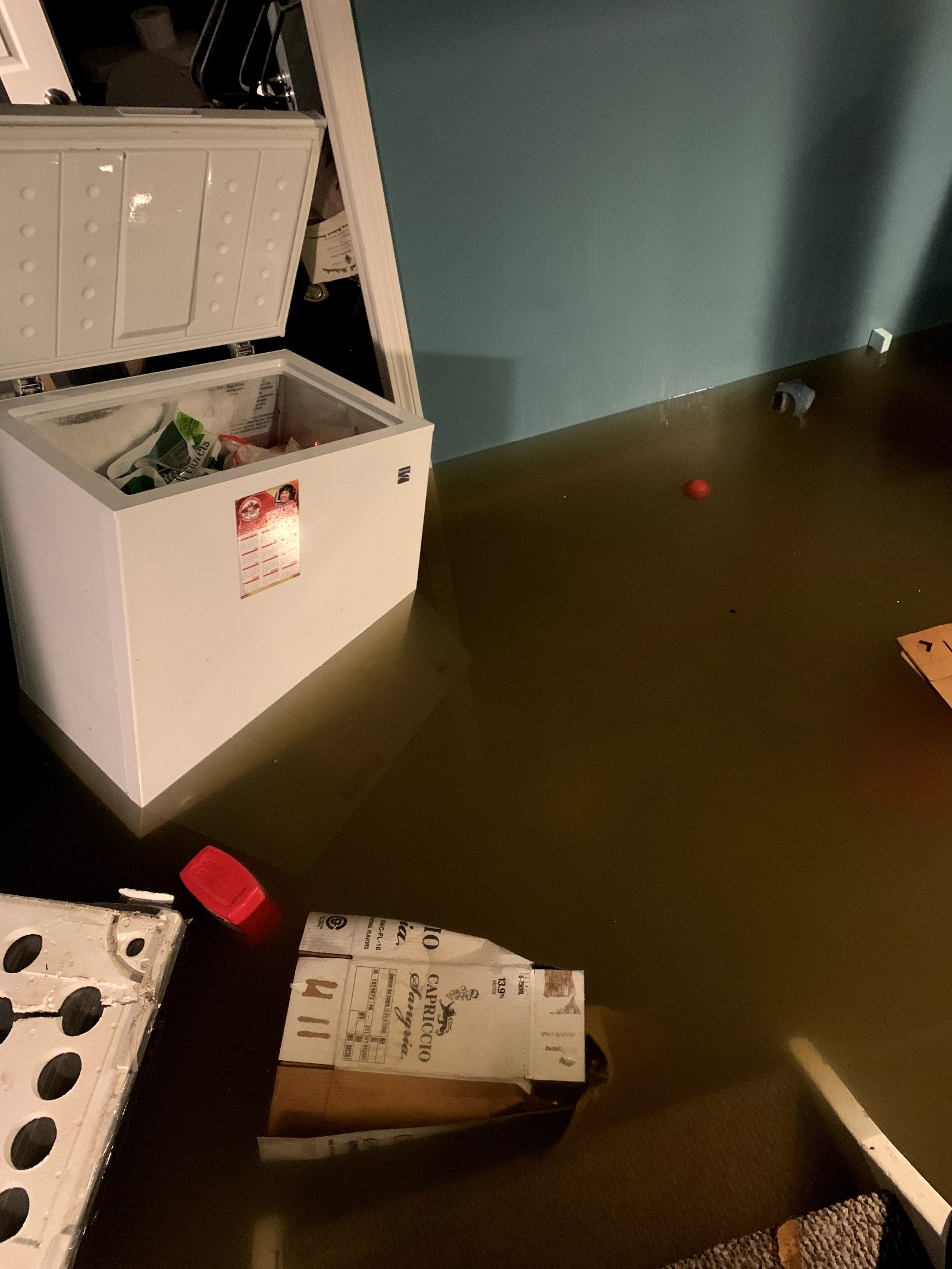

The rural, northern island of Wotho, for example, has long served as a “food basket” for the rest of the Marshall Islands. But officials found that a slew of disasters has jeopardized life there. Houses flood with every high tide, the airstrip goes underwater during big storms, household wells pull up salty water, salt-scourged breadfruit trees produce rotten fruit, and fish have abandoned bleached coral reefs.

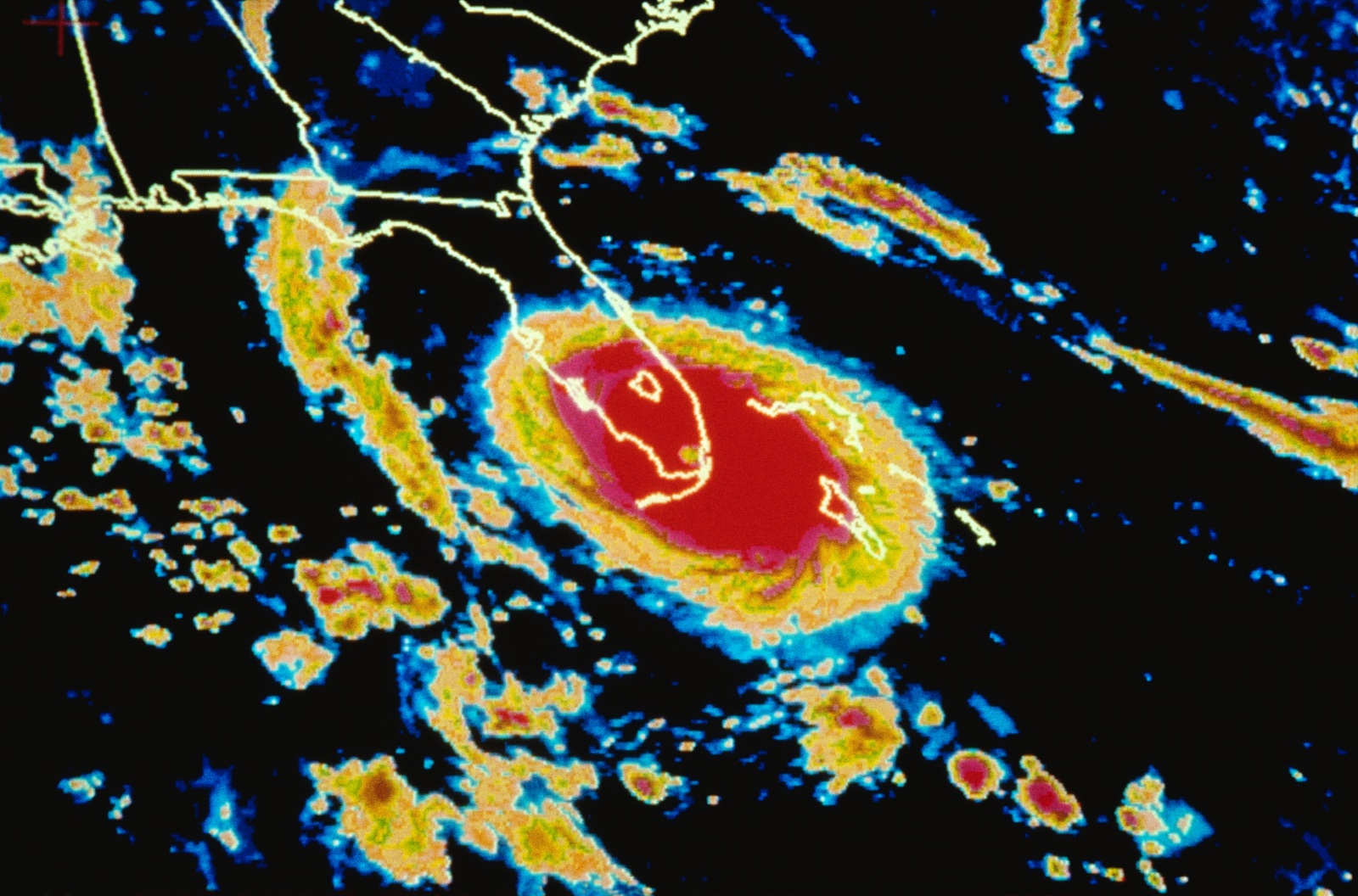

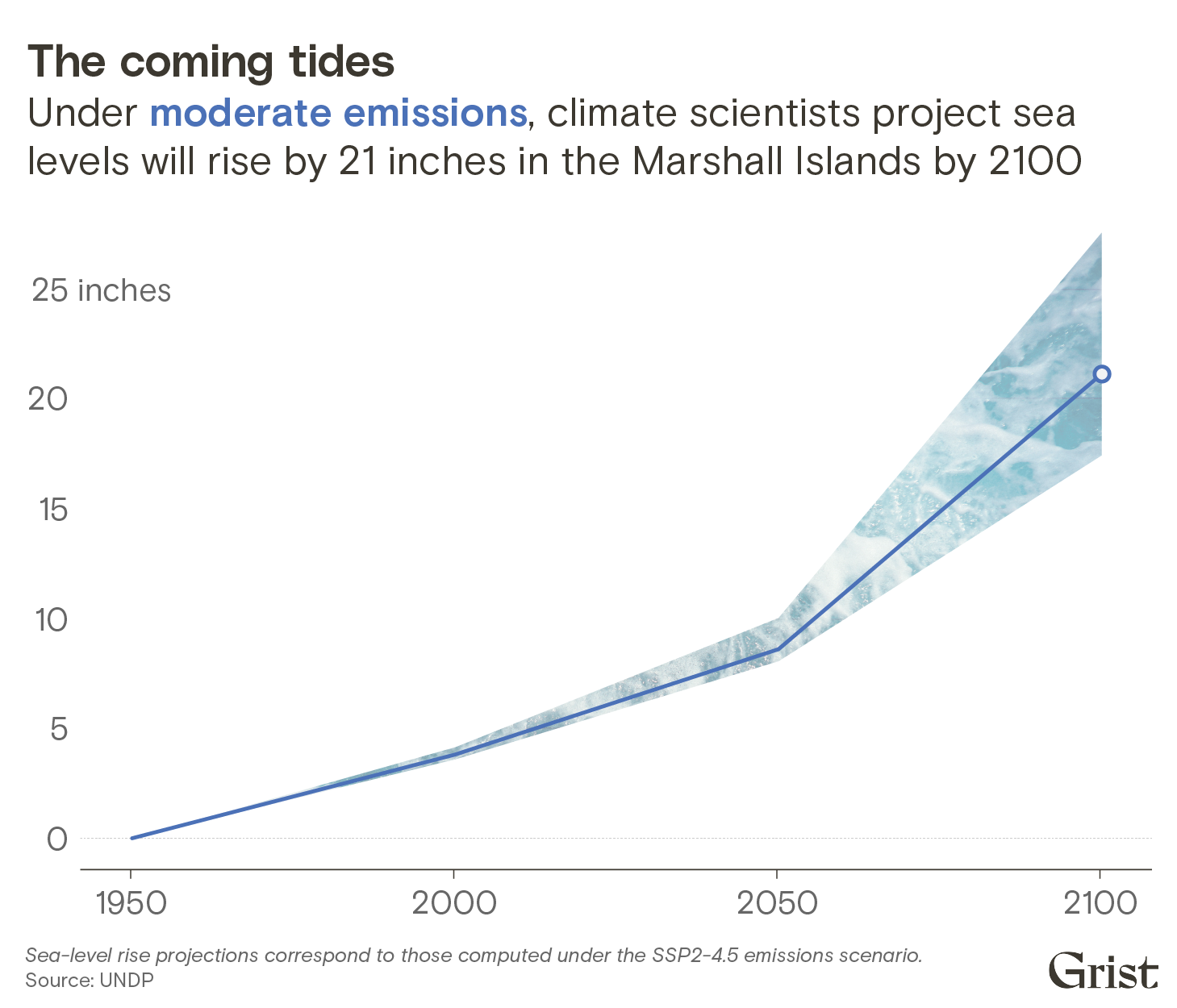

Science predicts it will only get worse. Even under the most optimistic projections, which assume immediate action to limit global warming, the Marshall Islands will experience almost two feet of sea-level rise before the end of the century. That’s enough to expose thousands more Marshallese citizens to constant flooding and extreme food and water insecurity, rendering some of the country’s islands all but unlivable. Under the worst projections, which predict more than six feet of sea-level rise by 2150, many islands and atolls would disappear underwater entirely.

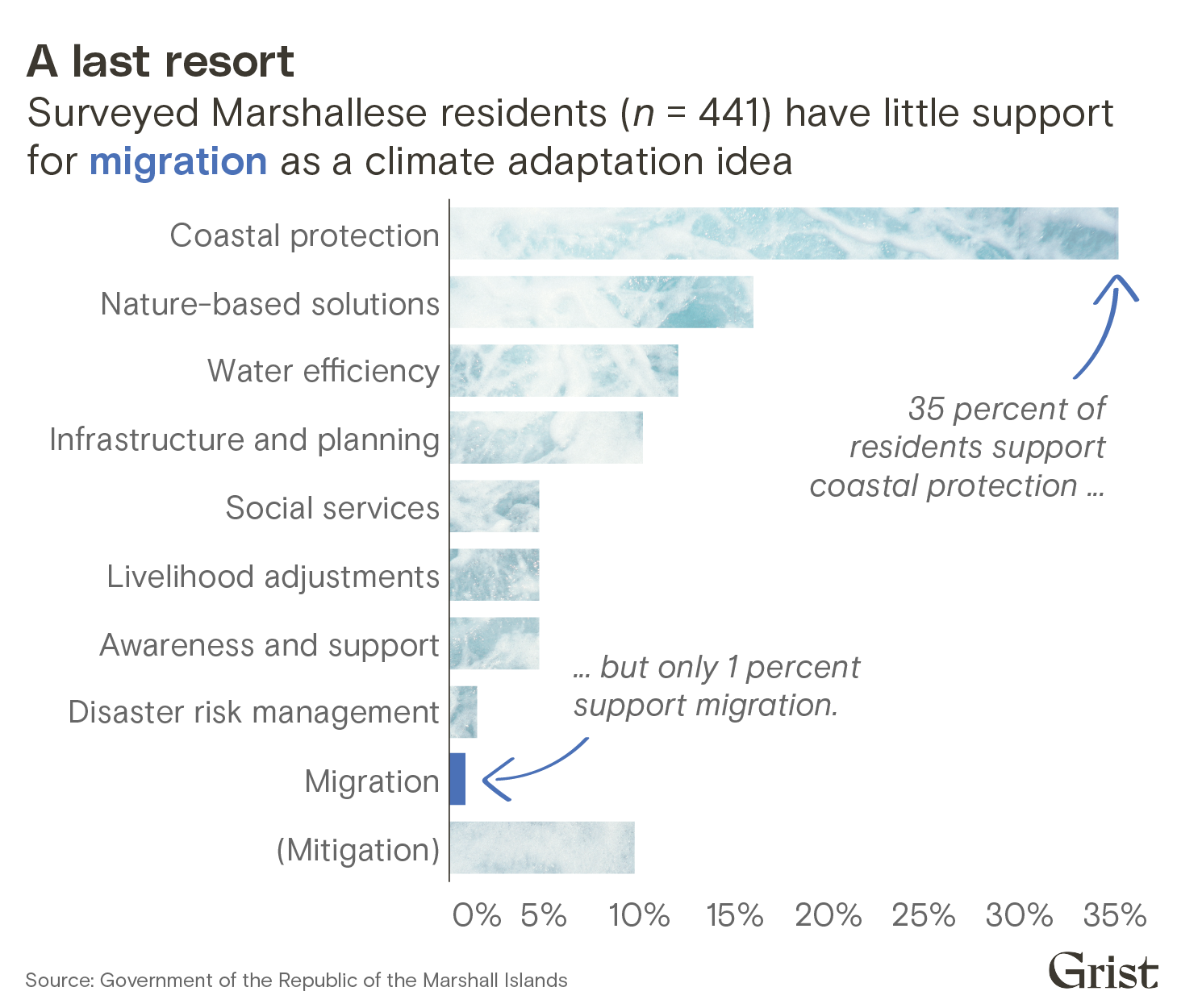

Even so, the community engagement process revealed that migrating away from their home islands is anathema to almost all Marshallese. More than 99 percent of interviewed residents rejected the idea of migration — as one respondent put it to an interviewer, “We will die here.”

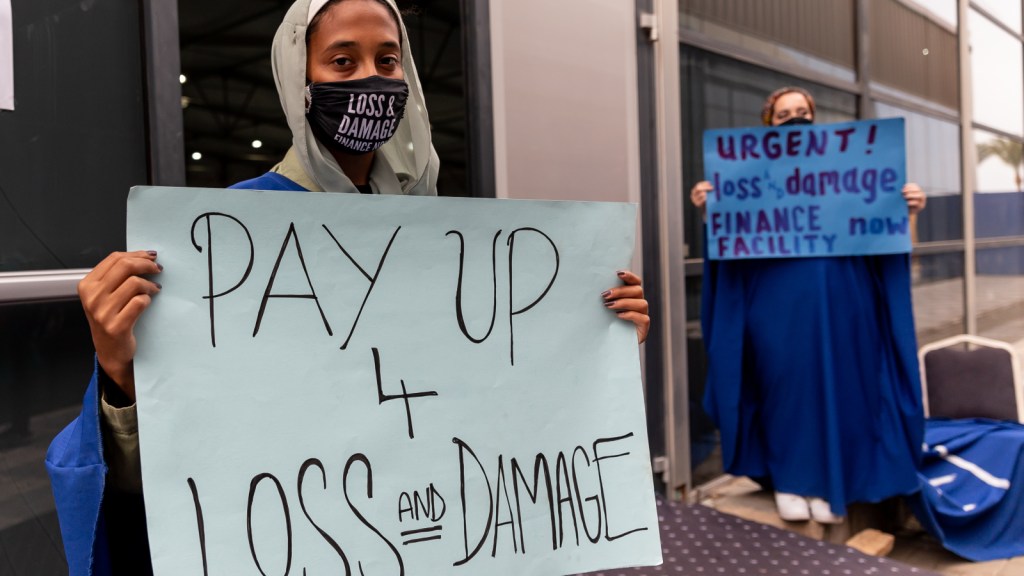

The plan arrives as climate negotiators at COP28 debate major new funding commitments to help developing countries adapt to climate change and deal with climate losses. Leaders from the Marshall Islands say their plan highlights the urgent need for billions of dollars of new adaptation funding from developed nations. In other parts of the world, adaptation means the difference between bad impacts and worse impacts. In the Marshall Islands, successful adaptation means the difference between survival and extinction.

“My hope for my own home is that it remains here long enough for me to give back to the land,” said Jobod Silk, a youth climate representative from the Marshall Islands who conducted community interviews for the plan. “I hope that we remain on our land, that we remain sovereign, and that we’re never labeled as climate change refugees.”

Climate change is not the first time residents of the Marshall Islands have dealt with environmental devastation. After the United States defeated Japan in World War II, it took control of the country through a trust backed by the United Nations. Over the course of a decade, the U.S. dropped more than 60 nuclear bombs on Bikini Atoll and other islands as part of a secretive weapons testing program. The fallout from these tests poisoned the water on nearby islands and caused higher rates of cancer and birth defects for many Marshallese. Fish near the U.S. military base on Kwajalein Island have been found to contain dangerous levels of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs.

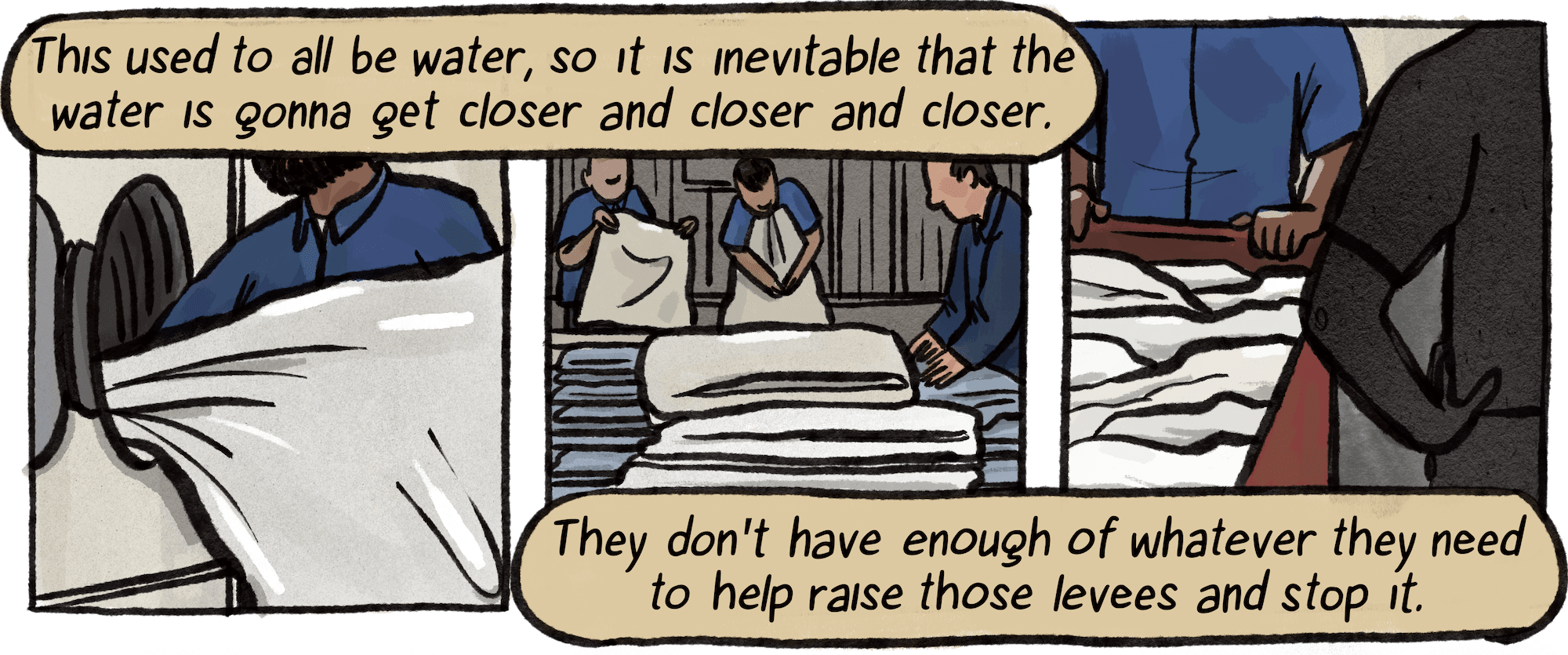

Now, a generation later, sea-level rise and drought are again disrupting life for many Marshallese, threatening the homes and health of families that fled nuclear fallout just a few decades ago. Even before the development of the new adaptation plan, many residents of vulnerable villages had already started to alter their behaviors to cope with the new reality of climate change. During site visits to outlying atolls, Marshallese officials witnessed residents of one island constructing makeshift seawalls out of trash. They found that fishermen on another island had started to fish as a collective in waters where reefs have degraded and fish stocks have plummeted, combining their efforts so that they catch enough food for their entire community.

In the short term, the new plan proposes to support these community-led adaptation efforts with billions of dollars of new money from other countries. U.N.-backed programs have already helped deliver rainwater-harvesting devices to outlying islands and build vertical vegetable gardens on others. With more money, the Marshallese government says it could expand air and sea shipments to these small islands to ensure a supply of substitute food, or provide canoes to every household as alternate transportation when roads are flooded. The plan defers to residents of outlying atolls by emphasizing what it calls “low-technology community initiatives and nature-based solutions” over engineered interventions like seawalls and dikes.

“This document is a self-determined document,” said Broderick Menke, an official at the Marshall Islands climate change directorate who served as the technical expert on the plan. “It’s not just the government making points, and it’s not just a consultant making decisions and providing answers. The roots of all of this is us coming together as the community and talking.”

In order to pursue these adaptation measures, the government will need to contemplate changes to the system of land ownership in the Marshall Islands. The country has almost no public land, and families pass down their properties along matrilineal lines, so the government can’t unilaterally build seawalls or set aside coastal areas for conservation, and disrupting this land tenure system would involve difficult conversations with traditional island leaders. The country also needs to update its environmental regulations and building codes in order to implement its short-term adaptation push.

Marshallese leaders say they can overcome these obstacles, and they stress that a fully funded portfolio of solutions would protect even the country’s most vulnerable islands for decades to come. But the plan also contains a grim warning that these adaptation efforts will not be able to protect the entire country indefinitely against future sea-level rise.

“The adaptation pathway for sparsely populated neighboring atolls and other islands comes down to buying time until sea level rise and other climate change impacts render the islands uninhabitable,” the plan says.

In addition to identifying adaptation strategies for droughts and flooding, the authors of the plan also had to create a procedure for deciding when and how to give up on protecting vulnerable areas. To that end, the plan lays out a phased “pathway” for adaptation, with “decision points” arriving over the next century as climate impacts worsen. This framework focuses attention and funding on short-term triage for vulnerable outlying islands like Wotho, and defers big decisions about the country’s future until later decades.

The first phase of the plan calls for the government to do everything possible over the next 20 years to protect vulnerable islands, leading up to a “decision point” some time between 2040 and 2050. When that point arrives, if it seems like climate change is going to overwhelm these islands despite adaptation efforts, officials must make a “decision regarding which atolls to protect and consolidate social services.” This wouldn’t involve moving any people or even buildings, but it might mean reducing government investment in education and health services.

A few decades later, in 2070, the plan calls for an even more difficult decision — officials must “decide which pieces of land are to be protected for the long term” and “build the protection infrastructure … to accommodate relocated populations.” In a sign of the dire outlook for future sea-level rise, the plan suggests choosing as few as four pieces of land for future investment, out of the 24 inhabited islands and atolls in the country right now.

Brandi Mueller / Getty Images

Adaptation experts said the Marshall Islands is one of the first countries to develop a long-term plan for relocating whole segments of its population.

“This is a noteworthy step in adaptation planning,” said Rachel Harrington-Abrams, a researcher at King’s College of London who studies relocation in vulnerable island states. She said the plan is the first from an atoll country like the Marshall Islands that “support[s] in situ adaptation while also enabling long-term planned relocation.” Harrington-Abrams added that island states such as Fiji and Vanuatu have planned to move vulnerable populations to higher ground, but these states have far more solid land than the Marshall Islands does.

The most likely candidates for long-term protection are Majuro and Ebeye, the country’s two main urban hubs. Together, these cities are already home to more than 70 percent of the Marshall Islands’ population, making them some of the most densely populated places in the Pacific. The plan predicts that further migration from rural islands to these cities is “very likely.”

But these urban hubs, too, are extremely vulnerable to sea-level rise: Even two feet would flood around one-third of Ebeye’s atoll and almost half of Majuro’s. If the government decides to stop protecting rural islands and retrench on the urban ones, it must also fortify these cities so that they can withstand future flooding. The country would begin by investing billions of dollars into new seawalls, dikes, drainage systems, and home elevations, as well as desalination machines and water treatment facilities to cope with saltwater intrusion. A new water treatment plant was installed on Ebeye in 2020 with support from the Australian government and the Asian Development Bank, giving residents of the city reliable access to clean running water for the first time.

Full protection against six feet of sea-level rise would require a much more radical adaptation strategy. The plan calls for the government to raise entire segments of land on Majuro and Ebeye by as much as 12½ feet, high enough to escape not only rising tides but also groundwater penetration. In addition to raising the existing cities, the country would also need to construct new reclaimed land by dredging the ocean floor. The plan projects that a new landmass to accommodate 10,000 people would need to be about 1.4 square miles, or a little larger than New York’s Central Park.

This type of land construction project has already been undertaken in the Maldives, which built an artificial island called Hulhumalé in the early 2000s to prepare for sea-level rise. That island is now home to more than 50,000 people. But the remoteness of the Marshall Islands, and the “technical feasibility” of land construction there, would likely drive the cost of such a construction project into the billions.

The last and most painful decision point, Marshallese officials found, will arrive at the year 2100. By that point, without massive investment in adaptation, many parts of the country will likely have become uninhabitable. The plan calls for leaders to make a profound choice about the future existence of the Marshall Islands itself.

“If by 2100, no decision can be made to protect areas of atolls to the [six-foot] sea level rise level, or if there is no funding for it, then the decision must be to help all population to migrate away from RMI,” or the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the plan says.

The most likely destination for these departing residents would be the United States: The Marshall Islands declared independence from the U.S. in 1979 but later signed a “compact of free association” with the country, allowing Marshallese residents unrestricted migration to the United States. In exchange, the U.S. exerts significant control over Marshallese waters and airspace, giving it a strategic military foothold in the Pacific.

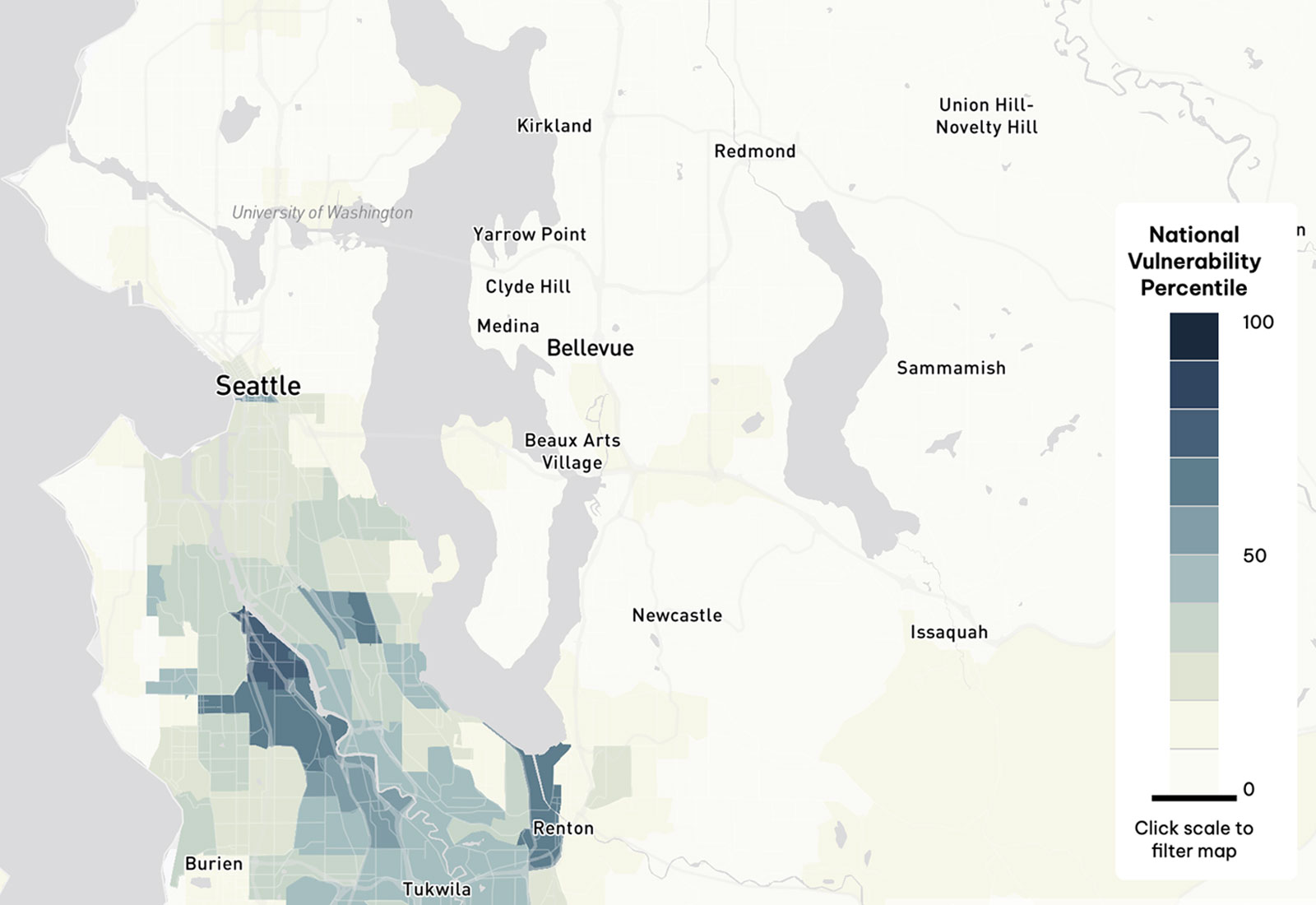

The country’s population has already fallen by around 20 percent over the past decade as many citizens leave seeking jobs and education in the U.S. The majority of these migrants have settled in Oregon, Washington, and Arkansas. More than 12,000 have settled in the city of Springdale, Arkansas, alone. The city now holds annual Marshallese festivals and cultural events.

The creators of the plan emphasize that international migration is an absolute last resort, and one that the overwhelming majority of Marshallese residents oppose. During the government’s hundred-plus community meetings, fewer than 1 percent of interviewed citizens expressed support for migration as a climate adaptation strategy, indicating an almost total rejection of relocation policies. The plan doesn’t go into detail about how to implement such policies, or about how the Marshall Islands’ government could provide support or restitution for residents who have to move.

The losses that will accompany this migration are impossible to quantify, said John Silk, the foreign minister, at the panel in September. A large-scale relocation would make it impossible for many Marshallese to be buried on their home islands, a key part of Marshallese culture, and it would further erase Indigenous navigation methods that Marshallese sailors have used for millennia.

“Loss to us is not just a financial loss or an economic loss; it’s a cultural loss if people have to migrate from their own home island to another place,” Silk said at the panel. “Even if you go to another part of the Marshall Islands, and you build a seawall, and we bring our people there, they will never feel at home, because they’re not.”

Despite the pain that would accompany such a large migratory movement, the creators of the adaptation plan view the plan as an optimistic document. If the Marshall Islands’ government can raise the money it needs for adaptation, it could also address some other challenges the country is already facing. It could bolster social services and health outcomes on rural outlying islands, reversing the trend of population loss and the rapid growth of Majuro and Ebeye. Such an investment in infrastructure and social resilience might even help stem the tide of out-migration to the United States.

“I think you can go even a step further, to bringing back the migrants that are going out of the Marshall Islands,” said Menke, the technical expert on the plan. “Marshallese go out there [to the United States] for education and for all these other services, but you know, they just have a … feeling of being away from home.”

The cost of achieving that future could run to an astonishing $35 billion, according to the plan, equivalent to around $800,000 for every current resident of the Marshall Islands. And the country needs to raise that money sooner rather than later, since the cost of adaptation will only increase as time goes on and climate impacts worsen.

Much of this money would need to come in the form of direct aid from rich countries like the United States, but the Marshall Islands could pull down some of it through international adaptation funds like the Green Climate Fund, or through multilateral development institutions such as the World Bank. If these aren’t enough, leaders may also need to pursue alternative financing mechanisms like an international tax on maritime shipping emissions, which the Marshall Islands and the Solomon Islands proposed in 2021.

Even so, rich countries aren’t currently providing anywhere near enough adaptation finance to fund the entire plan, said Rebecca Carter, the lead adaptation researcher at the World Resources Institute, an environmental research nonprofit.

“If it was just the Republic of Marshall Islands, maybe there would be enough, but when we start multiplying their numbers by how many other places are facing similar threats, that’s when it becomes really untenable,” she told Grist.

Leaders from the Marshall Islands hope their plan helps sway the international negotiations underway in Dubai. Negotiators are currently debating how much money developed countries should send poorer countries for climate adaptation, as well as how to measure the success of adaptation projects. The Marshall Islands’ in-depth adaptation plan shows both the urgent need for new funding, as well as the need to develop adaptation solutions in concert with affected communities, Jetn̄il-Kijiner says.

“I hope that it sheds light on the importance of adaptation and what communities like ours are being forced to plan for,” she said. “We’re trying to set a standard for how to engage with your own community and how to plan for these types of impacts.”

As the consequences of climate change in the Pacific grow more severe, the Marshall Islands and other small island states have become a leading force in international climate negotiations. The late Tony de Brum, a long-serving minister for the Republic, was a key architect of the Paris Agreement, and subsequent Marshallese leaders have pushed for even more ambitious mitigation targets, as well as big funding commitments for adaptation and climate reparations. (The country accounts for around .00001 percent of historical greenhouse gas emissions.)

Now Jetn̄il-Kijiner says the country’s adaptation plan could provide a blueprint for other countries facing down the threat of climate change. Instead of just assessing future risk or selecting infrastructure projects, leaders in the Marshall Islands used the planning process as an opportunity to deepen the bonds between the government and its citizens. They say the plan shows that it’s possible to pursue adaptation from the bottom up, rather than the top down.

“It’s a lot of responsibility to have to hold the hand of our community and say, ‘I’m sorry to tell you, but this is something that we have to face, but it’s OK, we’re going to face it together,’” Jetn̄il-Kijiner told Grist. “I think that’s something that takes a lot of delicacy.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Inside the Marshall Islands’ life-or-death plan to survive climate change on Dec 5, 2023.

This post was originally published on Grist.