This post was originally published on Al Jazeera – Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera.

-

Iran has dismissed scepticism over its development of hypersonic missiles, which could reach Israel in seven minutes.

-

Erdogan's rhetoric may be unfriendly towards Greece, but his predecessors were outright dangerous, many Greeks say.

This post was originally published on Al Jazeera – Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera.

-

The palatial modern art museum was badly damaged in the explosion that rocked the Lebanese capital.

This post was originally published on Al Jazeera – Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera.

-

Health, tech and saved wealth could turn an ageing workforce from an economic challenge into an advantage, say experts.

This post was originally published on Al Jazeera – Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera.

-

A fifth-generation fisherman finds an innovative way to remove and recycle plastic waste from the Mediterranean Sea.

This post was originally published on Al Jazeera – Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera.

-

In a speech delivered during last week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has emphasised the significance of the Voice of Parliament in redefining Australia as a nation. Speaking at the Lowitja O’Donoghue Oration in Adelaide, the Prime Minister expressed his belief that the Voice to Parliament could serve as a transformative force, even surpassing the achievements of the 1967 referendum. With passion and conviction, he called upon the nation to embrace a better future, one that addresses the historical injustices experienced by First Nations people and invited all Australians to walk together towards progress.

However, there are stark differences between the political landscape of 1967 and the present day. The Liberal Party today is a radical different party to the one of the Menzies era, and fear, loathing, and hatred have become more potent tools for mobilisation today: it was obvious that the federal Liberal Party was never going to support the Voice to Parliament and even before the legislation for the referendum was presented in Parliament, they had declared their allegiance to the “no” campaign. In a continuing pattern of misrepresentation and deceit, they have distorted information and levied baseless accusations against Prime Minister Albanese who, since his election victory in May 2022, has advocated for positive change and sought to address the issues facing Indigenous Australia.

The Prime Minister has been criticised in some quarters for his lack of courage and timidity on other reform initiatives but these criticisms cannot be levelled at him on the Voice to Parliament, driven by a conviction that it is ‘the right thing to do’, regardless of political ramifications. Also, there are significant challenges inherent in convincing the rest of Australia to support an initiative that seeks to rectify historical injustices, while facing staunch conservative opposition.

Among the opponents of the Voice to Parliament, speculation about ‘a secret plan’ to overturn future legislation has gained traction, despite a lack of any substantiation, as no such provision exists in the proposal for the Voice to Parliament, and the propagators of these unfounded theories often resort to ‘dog-whistle’ politics through media outlets such as News Corporation. This is in contrast to the extensive reports from the Solicitor–General which suggest that the Voice to Parliament will possess no legislative power, and primarily serve as a consultative body for Indigenous voices to be heard – which has been the intention of the Voice to Parliament all along.

In a misguided attempt to discredit the Voice to Parliament, some conservative groups are questioning its legitimacy by proposing the inclusion of other ethnic groups, such as the Chinese or Lebanese communities. Yet, this argument conveniently ignores the historical context and the unique plight faced by Indigenous Australians. Recognising the enduring history of Indigenous connection to the land, which spans over 60,000 years, it is essential to acknowledge the injustices suffered by these communities since 1788. While the mistreatment of other immigrant groups throughout Australia’s history of white settlement/invasion needs to be acknowledged, it pales in comparison to the systemic displacement and oppression faced by Indigenous Australians.

The Liberal Party race-based political games

It has to be remembered that the impetus of the Voice to Parliament can be traced back to the bipartisan act initiated by the Prime Minister at the time, Malcolm Turnbull, and then Leader of the Opposition, Bill Shorten in 2015, which later led to the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. While the subsequent Morrison government rejected incorporating the Voice to Parliament into the Constitution, it did at least express some lukewarm support for a ‘voice to government’. However, current opposition leader Peter Dutton has totally rejected the idea of federal government involvement and instead proposes limited council area involvement that would render the Voice to Parliament ineffective, a strategy which reveals the Liberal Party’s focus on political gamesmanship rather than genuine progress for First Nations people.

Critics argue that the Liberal Party’s motives extend beyond mere opposition to the Voice to Parliament, with suggestions that many prominent members of the party – such as Dutton and former Prime Minister Tony Abbott – wish to protect a vision of Australia that maintains an Anglosphere dominance and ‘white’ authority. While not overtly expressed, this power dynamic manifests in other ways, including through deliberate misinformation campaigns and the unleashing of anonymous trolls on social media platforms.

The Liberal Party’s campaign against the Voice of Parliament has included accusations of Albanese’s “moral blackmail” and trying to define and impose his views on Australia’s national conscience. It also matches up with the Liberal Party’s previous support for One Nation’s “it’s okay to be white” motion in the Senate in 2018, and the views of Senator George Brandis in 2014, that “people have the right to be bigots”.

While the Liberal Party’s tactics are obviously calculated for their political benefit, it’s a strategy which could ultimately backfire. The changing demographics of Australia, with a younger generation less inclined to respond to racist dog-whistling, suggest that the party’s strategy is out of touch with the evolving social landscape. Racism, though still present in Australia, is gradually losing its grip on society, and the majority of Australians are receptive to addressing historical injustices and valuing equality and inclusivity.

The Voice to Parliament is not without its imperfections and, once established – if it is successful in the forthcoming referendum – will need to undergo careful scrutiny to ensure fairness, openness, and broad representation within the Indigenous community which, in turn, can address long-ignored issues. The Voice to Parliament represents a crucial step toward a more inclusive and equitable society, signaling a commitment to progress and Indigenous empowerment.

As the path toward achieving the Voice to Parliament unfolds, it is evident that opposition and misrepresentations will persist. Australia stands on the precipice of an opportunity to redefine itself as a nation committed to rectifying past injustices and paving the way for a better future, where Indigenous voices are heard, respected, and valued. The journey may be challenging, but the Voice to Parliament represents a critical beacon of hope, progress, and unity for all Australians.

The post The conservative racist attacks on the Voice to Parliament appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

In a week dominated by revelations surrounding PwC – one of the world’s largest accounting firms – attention has been drawn to the alarming leaking of secret information from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to other consulting firms and PwC’s clients. The leaked information, which potentially holds valuable insights into the Australian government’s plans regarding multinational corporations and taxation, has sparked a heated debate on the issue of government outsourcing. It is now becoming evident that the disclosures made so far merely scratch the surface, with indications of more revelations to come, not just concerning PwC but other consulting firms as well.

The magnitude of this issue becomes apparent when examining the exorbitant amounts of money spent on consultants and outsourcing: during the final year of the Morrison government, an astonishing $20.8 billion was allocated to these services. To put this into perspective, this figure is equivalent to employing 54,000 full-time staff or 37 per cent of the entire federal government public service. While the Albanese government has expressed its intention to address this issue and curtail excessive outsourcing, immediate reductions are not feasible due to ongoing contracts that cannot be terminated abruptly, some of which have a duration spanning several years.

It is essential to acknowledge that certain areas of government activity require the specialised expertise of the private sector and reintegrating these functions back into the public service quickly poses significant challenges. It is now clear, however, that no amount of confidentiality agreements with external providers can guarantee the protection of sensitive material belonging to the federal government, emphasising the urgent need for a comprehensive review of the outsourcing practices.

A critical aspect that emerged during Senate hearings this week is that relationship between the ‘Big Four’ accounting firms – PwC, KPMG, EY and Deloitte – and political donations to parties on both sides of the political spectrum – over $4 million over the past decade. The conflict of interest arising from such financial contributions casts doubt on the fairness and impartiality of policy-making processes and there is a need for more robust regulations prohibiting these donations, considering their potential influence over governmental decisions and elections.

The Australian Greens Senator Barbara Pocock questioned Peter de Cure from the Tax Practitioners Board during the Senate hearings, and his responses shed light on the inadequacy of the current system’s response to the actions of PwC. The failure to consider whether PwC breached professional codes, particularly in acting honestly and with integrity, has raised serious concerns about the resolve and effectiveness of oversight committees. The absence of any referrals for financial penalties, despite the gravity of the situation, adds to the growing skepticism surrounding the regulatory mechanisms in place.

The ongoing Senate hearings continue to uncover shocking details, and it is anticipated that more revelations will follow. Beyond the questionable behaviour of individual consultants at PwC – such as the former head of international tax, Peter Collins – the larger issue at hand is the overreliance on external expertise, which has steadily increased since the 1980s. Influenced by neoliberal ideologies and a desire to distance themselves from anything remotely associated with communism after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, governments embraced the outsourcing trend, often to an extreme extent. However, the time has come for a substantial reduction in this reliance on the private sector, as the detrimental effects of excessive outsourcing become increasingly evident.

The issue of outsourcing also extends beyond consultants to the management of procurement from the private sector on behalf of the government. In the case of PwC, the lack of effective checks and balances allowed for the leakage of sensitive government information, exposing potential vulnerabilities in the system.

The current situation has brought into question the role of other bodies, such as the Australian Federal Police, in overseeing and addressing potential breaches. The revelation that the AFP received information about a confidentiality breach involving PwC back in 2018, without taking substantial action, highlights the need for a thorough investigation into the relationship between PwC, government agencies, and regulatory bodies. The integrity and trustworthiness of the government are vital for the effective functioning of democracy, and any compromise in these areas could have serious consequences.

Beyond the PwC scandal, there is a growing realisation that a broader re-evaluation of outsourcing practices is necessary. Privatisation, ethics, and the alignment of private sector interests with public goals are all critical aspects that demand attention. While the private sector can play a role in certain areas, infrastructure development and vital services are best managed by the government to ensure the public interest is served and prevent profit gouging at public expense.

Although calls for a Royal Commission have been made, some argue that a complete overhaul of the system, while maintaining essential services, may be a more effective approach. Rebuilding government operations from scratch with transparency, accountability, and the public interest at the forefront, could address the underlying issues that have led to the current state of affairs.

With the potential for further revelations and ongoing Senate hearings, the debate surrounding the role of consultants and the future of government outsourcing is likely to intensify in the coming weeks.

The Albanese government faces the challenge of striking a balance between utilising external expertise when needed and safeguarding national interests. It is a delicate task that requires careful consideration and a commitment to transparency, integrity, and the public interest.

The post PwC scandal sheds light on consultants and raises concerns over conflicts of interest appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

In a surprising turn of events, Mark McGowan, one of the most successful political leaders in Australian history, resigned this week as the Premier of Western Australia. McGowan, who had held the position for six years, cited exhaustion and a lack of energy to effectively continue in the role.

Having been in Parliament since 1996, McGowan’s political career spans over two decades. During his time as premier, he successfully implemented a progressive agenda in a state not traditionally known for its progressiveness. Despite facing criticisms of being too reliant on the mining industry and favouring media proprietors, McGowan enjoyed high approval ratings and managed the state’s finances competently.

Under McGowan’s leadership, Western Australia navigated the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic successfully. His management of the crisis earned him widespread praise, and this was followed up with the Labor Party secured a resounding victory in the 2021 election, winning 53 of the 59 lower House seats. With the control of the upper house as well, the Labor Party seems set for at least two more terms in office.

Resigning on his own terms, McGowan avoided the pitfalls that often befall long-term political leaders. The toll of the job, the constant decision-making, media pressure, and responsibilities took a personal toll on him. Recognising his limitations, he decided it was the right time to step away from the role he loved.

McGowan’s resignation is unique in the sense that he chose to leave at a time of his own choosing, rather than facing an election loss, a leadership challenge, or a scandal. The legacy McGowan leaves behind is a testament to his competence, affability, and successful governance.

While some predict a drop in support for the Labor Party following McGowan’s resignation, history has shown that state leadership transitions can have mixed outcomes. Previous resignations of successful leaders in states such as Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales, and Tasmania have resulted in varying degrees of political challenges for their respective parties.

The impact of McGowan’s departure on federal politics in Western Australia remains uncertain. While his popularity undoubtedly influenced the federal Labor Party’s success in the 2022 federal election, it is unclear how a change in state leadership will affect future federal outcomes. Nevertheless, McGowan’s legacy as a highly successful premier of Western Australia is expected to endure and, as time passes, a clearer assessment of this legacy will emerge.

While his critics point to certain issues like the state’s reliance on the mining industry, ongoing challenges in the hospital system, and several major incidents in the Banksia Hill juvenile detention centre, his accomplishments in managing the pandemic, overseeing the state’s finances, and implementing progressive policies are noteworthy. With a high approval rating and significant electoral success, McGowan is likely to be remembered as one of the great premiers of Western Australia.

The resignation of a leader of McGowan’s stature creates a void that will need to be filled. The new premier, Roger Cook, may face challenges in replicating the popularity and cut-through that McGowan achieved. However, with the support and groundwork laid by his predecessor, the Labor Party in Western Australia will still have a solid chance of success at the next state election, due in 2025.

As Western Australia bids farewell to Mark McGowan, his resignation marks the end of an era characterised by successful governance, progressive policies, and a strong mandate from the electorate. While the future holds uncertainties, McGowan’s contribution to the state will be remembered, and his departure opens up new opportunities for the state’s political landscape.

The post McGowan’s resignation leaves behind a model for successful political leadership appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

Racism in the media is a deeply entrenched issue that requires urgent attention. The recent case of ABC journalist Stan Grant, who has taken indefinite leave after facing a torrent of racist abuse, highlights the pervasive nature of discrimination faced by people of colour, women, and individuals from migrant backgrounds in the media and political spheres. Grant’s decision to step away from his role comes as a culmination of ongoing racist attacks he has experienced throughout his career.

It is important to recognise the role played by News Corporation, led by Rupert Murdoch, in perpetuating racism within the media landscape. News Corporation has a history of amplifying racism, as seen in their coverage of incidents such as Adam Goodes – hounded out of the AFL in 2015 – the Black Lives Matter movement, the ‘African gangs’ agenda pushed by the Liberal Party during 2019, and the current debate surrounding the Voice to Parliament. Their influence in shaping public opinion and promoting divisive narratives cannot be ignored.

However, it is not only News Corporation perpetuating racism in the media. Many other media outlets – including the ABC, Nine Media, Seven Network, Ten Media, and The Guardian – often fail to adequately address and combat racism. While some pay lip service to the issue, others – such as News Corporation – display outright hostility. This lack of action and accountability allows racism to persist within the industry, hindering progress towards a more inclusive society.

The power of social media exacerbates the problem, acting as a platform for hate speech and racist abuse. While discussions about combating racism often emerge in response to such incidents, little is done to address the root causes. It is crucial for the media industry to confront its own role in perpetuating racism and take concrete steps to rectify the situation.

Grant’s departure also raises concerns about the support offered by ABC management. He criticised the lack of support he received amid the abusive attacks and expressed disappointment in the ABC’s failure to address the role of News Corporation in fueling this racism. Grant’s sentiments were echoed by ABC News head Justin Stevens and managing director David Anderson, who accused News Corporation of relentlessly attacking the public broadcaster.

The relationship between the ABC and News Corporation has long been contentious, with News Corporation often criticising the ABC. The recent revelations at Senate estimate hearings, where ABC executives were questioned by Senator Sarah Hanson-Young, shed light on the extent of News Corporation’s influence and the lack of action taken by ABC management.

One crucial step towards combating racism in the media is reassessing the association between the ABC and News Corporation. Constantly inviting News Corporation journalists onto ABC programs should be reconsidered, as it provides a platform to a corporate entity that consistently displays disdain for the public broadcaster. Instead, the ABC should prioritise supporting marginalised voices and fostering a more inclusive and equitable media landscape.

Addressing racism requires a comprehensive approach that goes beyond overt acts of discrimination. It requires examining the language, narratives, and perspectives used in media coverage. The media industry must strive to be more inclusive, ensuring that diverse voices are not only heard but also respected and valued.

It is time for the media industry to reflect on its role in perpetuating racism and take meaningful action to bring about positive change. By supporting independent journalism and demanding accountability, we can work towards a society that values diversity, fosters respectful dialogue, and challenges discriminatory practices in all forms.

The battle for balanced reporting

It has to be remembered that News Corporation in Britain came under fire for unethical practices –the tapping of a deceased girl’s phone, with the aim of uncovering private messages, with many of the individuals responsible for this breach of ethics still retaining their positions within the company. This incident highlights that it was not an isolated event or a mere lapse in judgment by a few individuals, but rather a systemic problem within the organisation. In the context of this obvious lack of ethics, ABC programs such as Insiders should consider banning journalists from News Corporation appearing as panellists.

During the recent broadcast of King Charles’ coronation, the ABC organised a panel discussion on colonialism and its impact on Indigenous Australians. Invited guests, including Stan Grant, Craig Foster, Teela Reed, and Julian Leeser, engaged in a conversation about this critical topic. Surprisingly, the abuse and backlash were primarily directed at Stan Grant, despite him being an invited guest rather than the organiser of the panel. Conservative groups, including News Corporation, the Australian Monarchist League, and supporters of the royal family, spearheaded the offensive against Grant.

Critics argued that the timing of the discussion, which coincided with the coronation, was inappropriate. However, the conversation about the effects of colonisation and the future of the monarchy in Australia is crucial and should not be limited by ceremonial events. The strong negative reaction from conservatives reflects a resistance to open dialogue and a refusal to acknowledge the complexities of Australia’s history.

The response from News Corporation has been a doubling down on their attacks against the ABC, attempting to distance themselves from any association with the racist abuse directed at Stan Grant and other individuals. This denial of responsibility is disingenuous, as News Corporation has played a significant role in shaping public discourse and perpetuating divisive narratives.

While acknowledging that the ABC is not perfect, it is evident that racism in the media remains a persistent problem. Stan Grant highlighted the lack of support from ABC management during this challenging time. This lack of understanding and empathy can be attributed to the absence of Indigenous representation in senior management and the board of the ABC, and this limited diversity within these decision-making positions perpetuates a dismissive attitude towards racist attacks and prevents meaningful change.

Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive overhaul of the ABC’s board and management. As a nation, Australia must mature and foster a broader range of debates that reflect the diversity of its population. However, vested interests often impede progress, with News Corporation acting as the mouthpiece for those resisting change.

Senator Hanson-Young has introduced legislation for a federal inquiry into News Corporation – the outcome of this inquiry at this stage remains uncertain, but it represents an opportunity to examine the influence and practices of Rupert Murdoch and News Corporation in Australia. At 92 years old, it is essential for Murdoch to understand the criticisms leveled against him and the negative impact he has had on Australian media and politics, before he passes away.

In an ideal world, Murdoch would have faced legal consequences after the Leveson inquiry in 2011. The decline of print media, exacerbated by online platforms, has already weakened the power of traditional press barons like Murdoch and the dwindling subscription numbers and waning influence of News Corporation indicate a shifting media landscape.

As Australia strives for a more inclusive and equitable society, media organisations must recognise the need for greater diversity in their ranks. It is time for the mainstream media to evolve and accurately reflect the multicultural fabric of the nation. While change may be slow, it is crucial to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy and work towards a media landscape that embraces all perspectives. Only then can Australia truly mature as an independent nation and move away from the divisive media narratives that have plagued its history.

The post Racist media and attack-dog News Corp appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

In what is being hailed as a year of substantial achievements, the Labor government has completed its first year in office. Comparisons have been drawn to the successful first year of Hawke government from 1983 to 1984, highlighting the government’s progress on key priorities outlined during the 2022 election campaign. While significant strides have been made in most areas, challenges persist, particularly in climate change policy and economic reform. However, the government’s focus on competence and credibility has resonated with the public, leading to an overall positive perception of their first year in power.

The Labor government’s eight key priorities included establishing an anti-corruption commission, holding an employment summit, implementing the Respect At Work report recommendations, addressing climate change, reworking national agencies, reforming the aged care system, and making childcare more affordable.

The National Anti-Corruption Commission commences on 1 July 2023, many recommendations from the Respect At Work report have been implemented and the government is also on track to hold a referendum on a Voice to Parliament by the end of the year. Additionally, the Job Summit was held in September last year, several ideologically-driven national agencies were either abolished or restructured, aged care workers will receive a 15 per cent pay increase, and $5.4 billion has been allocated to make childcare cheaper.

However, the government’s progress on climate change policy has faltered and has not matched the rhetoric – certainly, the government has made several announcements and commitments to emissions reductions and electric vehicle policy, but more action that needs to be taken if Australia is to meet its global environmental targets.

Whistle-blower legislation is yet to be fully developed and while the federal Court case against Bernard Collaery was dropped in late 2022, the cases against Richard Boyle and David McBride are still continuing and they need to cease. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has made representations to the United States government, but Julian Assange is still languishing in Belmarsh Prison.

There are still over 1,100 refugees in closed immigration detention, including over 400 who have remained in detention for over two years. There were long-standing and far-reaching calls to substantially increase Jobseeker payments, but the government decided to ignore these and only raised the rate by $20 per week.

Rising inflation and cost-of-living pressures have also presented political difficulties for the government. Energy prices and concerns in areas such as climate change policy and economic reform require continued attention and action.

Despite these issues, it seems that Albanese’s focus on competence and credibility in government operations has been appreciated by the electorate and the absence of constant conflicts and culture wars, which were characteristic of previous Coalition governments, has been a welcome change. The government’s commitment to governing effectively and efficiently, rather than stoking fear and division, has resonated with the electorate’s desire for a stable administration.

Some critics have questioned the government’s cautious approach and its focus on setting up the basics of good governance rather than implementing broader progressive Labor policies. However, the government’s caution may stem from previous experiences, particularly the tumultuous Rudd–Gillard years from 2007 to 2013.

While there is still room for improvement and ongoing challenges to address, the Labor government has made significant progress in its first year. Rebuilding programs which can work in the public interest, and restoring trust in politics require careful planning and execution. The government’s commitment to competence and credibility has resonated positively with the public, leading to a more civil and respectful political environment.

Looking ahead, the government’s focus on long-term goals and strategic decision-making may contribute to their ability to retain power in future elections. However, it is crucial to continue addressing issues and implementing policies that align with public expectations and demands.

Calls for more action in the second year

Moving into its second year in office, in the context of a depleted and demoralised Liberal Party, the Labor government will need to ensure complacency doesn’t grow with Caucus and continues a commitment to surpassing the performance of previous administrations. The Morrison government between 2019–22 cannot serve as any form of yardstick of political performance, an administration riddled with incompetence and corruption, which fell far short of expected levels of good governance.

Scott Morrison’s tenure as Prime Minister was demonstrably poor, particularly in handling major events such as the 2019 bushfires and the subsequent COVID pandemic which commenced in 2020. Albanese, on the other hand, is yet to face similar challenges. The ability to lead during difficult times is seen as a true test of leadership, and although Morrison clearly failed in these tests, Albanese’s mettle remains untested, though optimism surrounds his potential performance.

The Labor government’s focus lies primarily on reworking the economy to benefit the people and reversing what it perceives as unfavourable policies implemented by previous Coalition governments. This endeavour is expected to be a significant test for the current administration, potentially shaping its term in office. While some supporters have voiced their dissatisfaction with the progress made thus far, politics is a delicate balance of achieving what is possible under prevailing circumstances.

Despite the absence of revolutionary change – which has frustrated its supporters – the Labor government has successfully fostered stability during its first year. Nevertheless, there are areas that require immediate attention and improvement. Environmental concerns, such as coal mine approvals, must be reassessed as a higher priority, considering the urgency of addressing climate change. Additionally, the welfare system is still in need of substantial reform on multiple fronts. These issues are identified as crucial matters that demand swift action.

Overall, the Labor government’s performance in its first year has been competent and polished. While recognising the need for ongoing progress, opinion polls have consistently provided the government with a positive assessment. There is a general acknowledgement that more work lies ahead, both in comparison to previous administrations and in achieving the government’s own goals. As the nation faces an uncertain future, the Labor government remains focused on realising its vision for a better Australia.

The post Labor’s first year marked by achievement and focus on competence appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

In the midst of discussions surrounding the recent budget and the opposition’s reply, the immediate political prospects of the Liberal–National Coalition remain uncertain. While the Budget Reply speech failed to provide substantial insights into the party’s direction, it is important to note that, at this stage of the political cycle, such details are not usually expected. However, the lack of clarity regarding the Coalition’s agenda, particularly if they are to regain power, is concerning.

The announcement of Stuart Robert’s retirement from politics adds another layer of complexity to this situation. Although the date of his departure is yet to be determined, it is likely to happen sooner rather than later. Robert represents the Queensland seat of Fadden, which is a stronghold for Peter Dutton and the Liberal–National Party, holding 21 of the 30 seats in Queensland. With Fadden secured by a margin of 10.6 per cent by the L–NP, it would be difficult for them to lose the seat. Nonetheless, Robert’s retirement raises questions about the future of the party and the path they hope to carve out for themselves.

The rumours still persist regarding former leader Scott Morrison’s potential departure from politics – Morrison has taken up an advisory role with the Center for New American Security, a smaller military thinktank based in the United States. These upcoming changes in federal politics indicate a period of transition and uncertainty on the horizon.

Robert’s retirement from politics can be seen as a positive move. As one of the ministers responsible for the Robodebt scandal, along Scott Morrison, his departure presents an opportunity for the Liberal–National Party to define its future trajectory. It also signals a chance to address the controversial actions taken by Robert and Morrison in relation to Robodebt and for the types of candidates it chooses in future preselections.

Looking at the internal dynamics within the Liberal Party, there seems to be a glimmer of hope. Katherine Deves overlooked for the vacant Senate seat in NSW – reportedly, she was told not to stand – may be a sign of wiser and cooler heads prevailing. Perhaps there are some in the Liberal Party who recognise that the electoral appeal of far-right ideologies is diminishing. Losing many elections across federal, state and territory jurisdictions should be a wake-up call, urging the party to consider alternative approaches. The upcoming byelections in Fadden and Cook will be telling, as they could shape the party’s future direction.

Robert’s questionable conduct, including accumulating unjustified expenses and the Robodebt debacle, does not leave a positive legacy. His fallout with Morrison over the Robodebt issue also further isolates him in opposition, leaving him with few allies. Considering the allegations surrounding Robert and any future National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) investigations, it is likely that he will be one of the prominent figures involved – it should be noted that these are only allegations at this stage, but they suggest that Robert’s exit from politics is a welcome development.

Dutton is just revisiting the Howard years

In his Budget Reply speech on Thursday night, Leader of the Opposition, Peter Dutton, attempted to rally his base supporters – possibly an appeal to One Nation supporters – however, his speech failed to impress and raised concerns about the direction of the party. Dutton’s attacks on the idea of a “big Australia” and immigration, along with his criticism of the increase in public servants in Canberra, reflected a continuation of the policies of past Liberal leaders such as Scott Morrison, Tony Abbott, and John Howard. Unfortunately for Dutton and the party, this approach is outdated and out of touch with contemporary politics.

One of Dutton’s main messages focused on the failures of the Labor Party, particularly on higher power prices, higher unemployment, and higher taxes. While there may be some validity to the argument about power prices, the claims of higher unemployment and higher taxes lack substantial evidence. It appears that Dutton is resorting to the same old tactics that have become synonymous with the Liberal Party, failing to offer fresh ideas or progressive solutions.

Demographically, the Liberal Party is facing a disastrous situation. The under-35 demographic shows little support for the party, unlike in the past when it enjoyed higher levels of support from young voters. The declining trend in younger voters aligning with the Liberal Party is alarming and indicates a lack of foundation upon which the party can build as individuals grow older and more conservative. While it is true that numbers, not just age, matter in politics, the fact remains that the Liberal Party is struggling to attract and retain a diverse voter base. Unless a substantial change occurs within the party, they face an uphill battle in future elections.

There are speculations within the Liberal Party about alternative leadership options, particularly the deputy leader Sussan Ley. Although there isn’t an active push to make her the leader at present, the party seems to be preparing for potential changes in leadership if the situation deteriorates further. Ley’s engagement in a listening tour and increased participation in parliamentary Question Time reflects her aspirations for leadership. However, it is worth noting that the Liberal Party, like any political entity, must be ready for any leadership transition, even as a contingency plan.

Another figure mentioned is Shadow Treasurer, Angus Taylor, but his recent inconsistencies and lack of credibility have tarnished his reputation. He fails to make a serious contribution to the party’s future.

The Liberal Party is undoubtedly in a difficult position. Dutton, is struggling to resonate with the public, and the party’s frontbench appears demoralised. While political parties need to be prepared with alternative leadership, it is surprising that Ley is considered a leader-in-waiting, even though she is the deputy leader – Ley’s past controversies, such as “accidentally” buying a unit on the Gold Coast during a parliamentary business trip, have left a negative impression. Her lack of popularity among the wider community hinders her chances of becoming an electorally acceptable face for the Liberal Party.

Additionally, Taylor’s involvement in questionable activities, such as his involvement in Eastern Australia Agriculture – an entity established under a cloak of secrecy in the Cayman Islands – and alleging forged travel documents in an attempt to support a political campaign for his wife, Louise Clegg, to run for position of Lord Mayor of Sydney, has further damaged his standing. The party needs a leader who can tap into the zeitgeist and reinvigorate the Liberal brand, but such a figure is currently lacking.

The Liberal Party is facing an uncertain future. It must confront the reality of its dwindling support among younger voters and the need for new ideas that align with the current era. While Ley might be the likely candidate for leadership – if it does come to that – the truth is that whoever leads the party at this moment is bound to be irrelevant. The Liberal Party must undergo significant changes to regain relevance and appeal to a broader spectrum of voters.

The post Budget Reply: Uncertain path forward for the Liberal Party appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister James Marape has revealed that about K100,000 (about NZ$46,000) was paid to the kidnappers for the release of the three remaining hostages in the Bosavi mountains in the Southern Highlands province at the weekend.

The three hostages, an Australian-resident New Zealand professor and his two female colleagues, were set free yesterday.

In a news conference today, Prime Minister Marape clarified that the money was given through community leaders for the release of the hostages.

- READ MORE: Nightmare over for final 3 PNG freed hostages – police hunt their captors

- Prime Minister Marape warns police will come down hard on criminals

- PNG state pays partial ransom for release of the hostages

- Two countries, two kidnappings – Port Moresby shows Jakarta how it’s done with 3 PNG hostages freed

- Other PNG hostage crisis reports

”There was no K3.5 million paid [NZ$1.6 million — the original kidnappers’ demand]. The liaison money exchanged was K100,000 paid through the community leaders for a liaison to take place.

“The demand was very high and they maintained it all the way through, but we had to break the ice and ensure the safe return of the captives,” said Marape.

-

It was the day before the funeral of Cardinal George Pell, whose body had been shipped from the Vatican to lie in state at St Mary’s Cathedral after his death a couple of weeks earlier.

A friend and I joined others at 7.30am in the forecourt of the Gothic pile in the heart of Sydney’s CBD. It was a vigil to tie ribbons in memory of victim–survivors of abuse. The mood was peaceful but determined. Some shed tears or talked quietly with others. Large bags of ribbons were shared around. All of us were busy lacing the ironwork fence that rings the citadel. Within an hour, there was an extraordinary display of solidarity. Ribbons of every colour of the rainbow, densely packed, animated by the morning breeze as the sun rose higher in the sky, making spectacular shadows across the flagstones. Each and every ribbon was the voice of a victim or survivor, no longer silenced, raised against the atrocities of the clergy in the symbolic house of the perpetrators.

Pell’s carcass was to arrive that morning. We do not even need to go to the question of his personal innocence or otherwise of heinous abuse of children. Read the testimonies of those who spoke out about him: they are compelling.

Ribbons are illuminated by the sun during an early morning survivors’ vigil at St Mary’s Cathedral. Pic: AM Jonson On his watch, members of a ruthless multinational organisation – of which Pell was, in the end, the most senior Australian leader – systematically and criminally abused thousands of the most vulnerable – defenceless children entrusted to church schools and presbyteries. Infant and primary school kids, pre-teens and teens; fondled, penetrated, fellated, forced to perform sex acts, raped, damaged beyond repair, threatened that they must not tell – and blamed if they did tell. They were told they were sinners; that it was their fault; that they deserved it. Children whose sense of personhood and safety – the integrity of their being – was repeatedly violated at a level so profound, so cellular, that it was incompatible with life. Betrayed children who internalised the shame of their violation like a cancer.

The consequences are familiar. Some of us never recovered, and struggled with lifelong trauma and mental injury. Some grew up and drowned their misery in a bottle, or decided their only recourse was to permanently end the pain. My own brother was a clever, sensitive child, who went from dux of a Catholic school, to alcoholic, to junkie, to the disability pension. He contracted hepatitis C and liver cancer, and died early. He had tried to tell but was met with punitive disbelief at his boarding school, which said he was disturbed, a liar and a fantasist who needed reforming.

Pell’s role in the institutional sexual abuse of children in the Catholic church is well documented. To protect the church, pedophile perpetrators were moved from parish to parish like chess pieces in an insidious game. In other words, they were actively enabled to continue to perpetrate, and the children were their helpless pawns. Amongst many, the most notorious of these was Gerald Ridsdale of the Ballarat diocese, the epicentre of clerical sexual abuse in this country. As the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse found, Pell was involved in decisions to move Ridsdale from parish to parish, and aware of Ridsdale’s offending. In his role as Episcopal Vicar for Education, Pell had been alerted to allegations about abuses of children by clergy in Ballarat as early as 1973.

Yet, there was Pell in 1993, steadfast at Ridsdale’s side, acting as support person as Ridsdale entered Court to be tried and convicted. Many of the victims of Ridsdale and others in the diocese did not survive. The Commission was told that of the 33 children in the Grade 4 class of 1974 at St Alipius Ballarat, twelve took their own lives.

The fences around St Mary’s Cathedral were covered with hundreds of ribbons, each one representing the voice of a victim or survivor of child abuse by Catholic clergy. Pic: AM Jonson In short, the Commission established once and for all, that Pell knew about child abuse and failed to act, rejecting much of his evidence as “implausible” or “inconceivable”.

Survivors who raised the alarm were disbelieved, their claims minimised, their accounts silenced. Pell’s engineering of the egregious Melbourne Response when he was archbishop there is a case in point. This was an aggressive organisational damage-control scheme designed to limit the church’s liability at the expense of victims. People were paid a pittance of $50,000 to shut up and required to sign away any right they may have to a future legal claim against the institution. Survivors have spoken about the harm done by the scheme.

Those who appealed directly to Pell were brutally rebuffed. Chrissie and Anthony Foster’s two daughters were in primary school when they were repeatedly raped by Melbourne priest Kevin O’Donnell. One took her life, the other turned to drinking and is permanently incapacitated after being hit by a car. The Fosters said that Pell, then archbishop of Melbourne, showed a “sociopathic lack of empathy” when they approached him in 1997 – after O’Donnell had been tried and convicted of abusing other children – threatening that they had better be able to prove their allegations in court.

In Sydney, as archbishop, he was a central architect of the Ellis defence, the strategy designed to shirk the church’s responsibility for the clergy’s crimes, and render it immune to liability for compensation by asserting that the church does not exist as a legal entity, and therefore cannot be sued. Perverse legal abuse was, in other words, heaped on sexual abuse. The NSW LNP government found this so unconscionable that it stepped in to make laws allowing survivors to sue the church.

That day, at the ribboning vigil at St Mary’s, Pell’s former stronghold, there was a temporary victory of sorts. During the week prior to Pell’s funeral, church authorities had been removing ribbons placed by survivors. That seemed to be the policy of the archdiocese, unlike, for example, in Ballarat, where the practice of tying ribbons originated. On this day, a church official – a coiffed lady with a clipboard bearing documents with the St Mary’s logo – came to address the victim–survivors. She spoke to Paul, a Ballarat leader and St Alipius survivor who was there to raise his voice on behalf of his brother who took his own life 10 years ago. The functionary said that the dean of the cathedral had agreed that ribbons would be removed only from the side of the church and would remain at the front. Paul, dignified and gracious to a fault, thanked her.

The ribbons remained all day, and drove hundreds of media stories, bearing witness to the record of the man about to be interred.

Later that night of the vigil, my friend and I walked back by the cathedral. All along the fence, front and side, were beefy men in plain clothes, wielding box cutters, hacking off the ribbons and throwing them in garbage bags – self-appointed custodians of, as one told me, “the house of god”, which the ribbons “disrespected”. Some had brought their wives and children, who were also busy removing ribbons. I tried to talk to the men about what the ribbons represented but it was pointless, and the situation was intimidating. I wish I’d had the presence of mind to call the police: it is an offence to carry knives in a public place without a reasonable excuse. By the time their work was done, the ribbons were gone. Every single one.

Pell’s requiem mass went ahead the next day. The faithful attended to honour their man – applauding loudly as eulogist Tony Abbott proclaimed Pell a “saint for our times”, a “soldier of truth” – while members of the LGBTQI+ community gathered across the road to give Pell a rousing send-off to the strains of ‘Highway to Hell’ (Pell remained a virulent homophobe up to his final years). Not even Opus Dei member, NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet, could bring himself to attend, and the Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, and Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, were an emphatic no-show (Andrews’ response when asked if he would have a state funeral for Pell brought comfort to many: “I couldn’t think of anything that would be more distressing for victim-survivors than that… I will not do that.”)

Let’s allow the dead man to have the last word. On the church’s duty of care to children, he infamously said that it was no more culpable for priests’ actions than a trucking company would be for a driver who molested a woman. On the Catholic clergy’s sexual crimes against children, he said “abortion is a worse moral scandal than priests abusing young people”. At the Royal Commission, where the catastrophic scale of Catholic priests’ crimes was laid bare in excruciating detail, Pell – this prince of the church, this saint – was asked about Gerald Ridsdale’s offending. His reply drew gasps from the audience and is etched in survivors’ memories: “it was a sad story” he said, but “not of much interest to me”.

These immortal words stand as his epitaph.

For Paul J.

AM Jonson is a crumb-free maiden who’s not going to take it anymore.

The post Shredding the ribbons of George Pell’s legacy | Guest post appeared first on New Politics.

This post was originally published on New Politics.

-

Civil society organisations which make up the National Alliance for Criminal Code Reform have slammed the decision by the Indonesian government and the House of Representatives (DPR) to ratify the Draft Criminal Code (RKUHP) which is seen as still containing a number of controversial articles, reports CNN Indonesia.

Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) chairperson Muhammad Isnur criticised the DPR and the government because the enactment of the law was rushed and did not involve public participation.

According to Isnur, a number of articles in the RKUHP will take Indonesian society into a period of being “colonised” by its own government.

- READ MORE: Protests erupt across Indonesia after House ratifies ‘colonial’ Criminal Code

- Other reports on the Indonesian Criminal Code

“Indeed the latest version of this draft regulation was only published on November 30, 2022, and still contained a series of problematic articles which have been opposed by the public because it will carry Indonesian society into an era of being colonised by its own government,” said Isnur in a statement.

The Civil Coalition, as conveyed by Isnur, has highlighted a number of articles in the RKUHP which are anti-democratic, perpetuate corruption, silence press freedom, obstruct academic freedom and regulate the public’s private lives.

According to Isnur, these articles will only be “sharp below but blunt above”, meaning they will come down hard on the poor but go easy on the rich, and it would make it difficult to prosecute crimes committed by corporations against the people.

“Once again this will be a regulation which is sharp below, blunt above, because it will be difficult to prosecute criminal corporations that violate the rights of communities and workers,” he said.

Criminalised over ideas

The Coalition for example highlighted Article 188 which criminalises anyone who spreads communist, Marxist or Leninist ideas, or other ideas which conflict with the state ideology of Pancasila.According to Isnur, the article is ambiguous because it does not contain an explanation on who has the authority to determine if an idea conflicts with Pancasila.

According to Isnur, Article 188 has the potential to criminalise anyone, particularly government opponents, because it does not contain an explanation about which ideas conflict with Pancasila.

“This is a rubber [catchall] article and could revive the concept of crimes of subversion as occurred in the New Order era [of former president Suharto],” he said.

Then there are Articles 240 and 241 on insulting the government and state institutions.

He believes that these articles also have the potential to be “rubber” articles because they do not provide a definition of an insult. He is also concerned that the articles will be used to silence criticism against the government or state institutions.

The Coalition believes that there are still at least 14 problematic articles in the RKUHP. Aside from the spreading of communist ideas and insulting state institutions, there are several other articles such as those on morality, cohabitation and criminalising parades and protest actions.

Law ‘confusing’

The DPR earlier passed the RKUHP into law during a plenary meeting. A number of parties believe that the new law is confusing and contains problematic articles. These include the articles on insulting the president, makar (treason, subversion, rebellion), insulting state institutions, adultery and cohabitation and “fake news”.Justice and Human Rights Minister Yasonna H. Laoly has invited members of the public to challenge the law in the Constitutional Court if they feel that there are articles that conflict with the constitution.

“So we must go through constitutional mechanisms, right. So we’re more civilised, be better at obeying the constitution, the law. So if it’s ratified into law the most correct mechanism is a judicial review,” said Laoly earlier.

Deputy Justice and Prosperity Minister Edward Omar Sharif Hiariej, meanwhile, is asking those who consider the law to be problematic or rushed to come and debate the issue with the ministry.

“You try answering yourself, yeah, is 59 years rushed? If it is said that many oppose it, how many? What is the substance? Come and debate it with us, we’re ready and we are truly convinced that if its tested it will be rejected,” said Hiariej.

Translated by James Balowski for IndoLeft News. The original title of the article was YLBHI Kecam Pengesahan RKUHP: Masyarakat Dijajah Pemerintah Sendiri. Republished with permission.

-

Our wildly popular VegNews Holiday Vegan Cookie Contest is back, and we can’t wait to find the best holiday cookie recipe on the planet! Do you have a perfected vegan cookie recipe that puts the Sugar Plum fairies to shame? Whether it’s your grandmother’s gingerbread or a recipe inspired by whatever ingredients happen to be in your kitchen, we’re looking for the best holiday cookies on the planet. So bust out your best apron, your biggest tub of vegan butter, and your favorite egg replacer, and show us how your holiday cookie crumbles. Dazzle VegNews’ editors with your sweet treat, and you might win a Year of Vegan Cookies from Outstanding Foods (yep, the beloved vegan cheese puff brand will soon be debuting cookies, and you could win an annual supply!). Plus, your winning recipe will be showcased on VegNews.com and across all of our social media platforms.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Submit your vegan holiday cookie recipe by Sunday, December 18 @ midnight PST. Have more than one favorite? Enter as many as you’d like! All cookie recipe submissions must be original.

- VegNews’ editors will choose 10 finalists and bake like crazy to determine our favorites.

- The top three vegan holiday cookies of 2022 will be announced December 23 and shared on VegNews.com and across all of our social media.

So what do you win if you’re one of our top three winning cookies? Vegan cookies, of course! For our First Place winner, we’ll be sending you a Year of Vegan Cookies from Outstanding Foods in flavors like Chocolate Chip, Double Chocolate Chip, and Oatmeal Raisin. For our Second and Third Place winners, you’ll receive a case of these incredible, soon-to-launch vegan cookies. Just think, you could be among the first in the world to try Outstanding Foods’ brand-new cookies. All you have to do is enter your favorite holiday vegan cookie recipe!

This post was originally published on VegNews.com.

-

Do you go as gaga for new Trader Joe’s products as we do? Well, we’re not sure that’s humanly possible, but with more plant-based options than ever appearing on the shelves of TJ’s, shoppers like us are flocking there for our vegan fix. Lucky for us die-hard fans, the holiday season’s new items have debuted, which is why we’re stocking up on affordably priced Thanksgiving essentials, vegan whipped cream, and fancy beverages. There are few things as fun and mood-setting as leaving this cult favorite grocer with bags of scented pinecones, dairy-free nogs, and all the appetizers and snacks to host one incredible holiday party.

Is Trader Joe’s vegan-friendly?

Trader Joe’s is well known for its private label and Trader Joe’s exclusive goods. Over the years, the grocer has debuted its own creamy, vegan almond milk chocolate bars; dairy-free vegan salmon cream cheese complete with konjac-based salmon, capers, lemon juice, dill weed, and other flavorings; ultra-affordable vegan meat loaded pizzas (just $6!); and carries over 70 delicious plant-based products that we can’t get enough of.

Plus, the grocer was one of the first brick-and-mortar retailers to offer Boursin’s Dairy-Free cheese spread and was one of the first to launch its own plant-based version of turkey burgers.

The grocer also has big plans for the future with product developers at Trader Joe’s working to add vegan seafood to the chain’s offerings. Amy Gaston-Morales, category manager of Deli, Frozen Meat, Seafood, Meatless, and Fresh Beverage at Trader Joe’s revealed, “We don’t have options yet within our stores for a plant-based seafood product but there are crab cakes out on the market or scallops or tuna replacements. So we’re really looking more at the seafood to make sure that we’ve covered all the proteins that customers are familiar with and bringing in the best versions of those.” And with this year’s launch of Trader Joe’s Vegan Salmonesque Spread, the chain is right on track.

In addition to seafood options, the grocer has also announced major plans to reduce its plastic usage by selling more produce (such as apples, potatoes, and pears) as loose items instead, replacing plastic wrappers on flower bouquets with renewable materials, eliminating non-recyclable plastic and foil pouches from its tea packages, and replacing styrofoam trays in produce packaging with compostable trays. While it remains to be seen if the chain will follow through on its plastic reduction message, doing so would eliminate more than 1 million pounds of plastic from its stores.

Vegan holiday products at Trader Joe’s

While we can’t wait to see what’s next from the cult-favorite grocery chain, we’re turning our focus for now to its incredible nutmeg-spiced, cinnamon-scented, chocolate-dipped goods. Here are our picks for the can’t-miss Trader Joe’s finds of the moment:

@trader_joes_treasure_hunt/Instagram

@trader_joes_treasure_hunt/Instagram1 Oat Nog

When O’Nog begins appearing on store shelves, we know the holiday season is here. This creamy, lightly spiced, festive beverage is perfect for serving at your holiday parties.

@traderjoeshungry/Instagram

@traderjoeshungry/Instagram2 Vegan Gingerbread Loaf

This perfectly moist, ginger- and cinnamon-spiced loaf is found in the baked goods section of the store. Slice up and serve with a hot cup of tea for the ultimate night in.

@bigboxvegan/Instagram

@bigboxvegan/Instagram3 Mini Peppermint Marshmallows

We’re topping our hot chocolates with these adorable, mini, gelatin-free vegan marshmallows this holiday season. Toss them into chocolate cookie dough, pre-baking, for a delicious vegan hot chocolate cookie.

@veganreviewsatoz/Instagram

@veganreviewsatoz/Instagram4 Pumpkin-Flavored Joe Joe’s

Everyone’s favorite Trader Joe’s cookie has gotten a fall makeover. These seasonal cookie sandwiches are plant-based and totally irresistable.

@thatjerseyveghead/Instagram

@thatjerseyveghead/Instagram5 Pumpkin Oat Beverage

This lightly spiced oat milk has all the flavors of pumpkin spice season and is delicious for whirling into seasonally inspired smoothies and shakes.

@trader_joes_tre

6 Everything But The Leftovers Seasoning

This seasoning will make everything taste like a holiday feast. We’re using it to roast veggies, season tofu, and spinkle onto vegan chicken strips before tossing into a salad.

@veganfoodtrek/Instagram

@veganfoodtrek/Instagram7 Gingerbread Oat Latte

Trade in your normal latte for this seasonal oat milk cold brew latte with wintery spices, such as ginger, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Each sip brings a heady caffeine buzz with gentle heat and soothing creaminess from the thick oat milk.

@foxwithsnacks/Instagram

@foxwithsnacks/Instagram8 Breaded Turkey-Less Stuffed Roast with Gravy

Simplify your holidays by picking up this ready-made turkey-less roast for your meaty main, which comes complete with rich vegan gravy.

@binaryseasonings/Instagram

@binaryseasonings/Instagram9 Scandinavian Tidings Gummies

These soft and chewy fruit gummies in the shape of Christmas trees, stars, and ornaments, are totally gelatin-free, making them suitable for vegans.

@traderjoesnew/Instagram

@traderjoesnew/Instagram10 Gingerbread Cake & Cookie Mix

Simply swap in a vegan egg replacer, and you’ve got another easily veganized seasonal baking mix. Make it even better by topping with Trader Joe’s new vegan Coconut Whipped Topping!

Trader Joe’s

Trader Joe’s11 Thanksgiving Stuffing Seasoned Kettle Chips

When a snack craving hits, you’ll be glad you picked up a bag of these herbed potato chips. And even if there are no leftovers that make it through your Thanksgiving feast, these chips will still bring the spirit of leftovers to your post-holiday snacking.

@appetitesathome/Instagram

@appetitesathome/Instagram12 Candy Cane Joe-Joe’s

Everyone’s favorite Christmas-inspired cookies are back on shelves, and we can’t wait to dip them in almond milk, bake them into seasonal desserts, and eat them straight from the box. NOTE: The gluten-free version is not vegan.

Trader Joe’s

Trader Joe’s13 Sparkling Pomegranate Punch

This bubbly beverage is bright, richly fruity, and perfectly suited to refresh your holiday spirits.

Trader Joe’s

Trader Joe’s14Cranberry Sauce

Fresh-made cranberry sauce has never been this easy. Pick up this holiday staple during your next grocery run to wow your dinner guests.

This post was originally published on VegNews.com.

-

COMMENTARY: By Michael Field

The ruling FijiFirst Party has released its candidate list for the general election on December 14.

With it came some dubious biographies composed by candidates which voters will have to delve into over the coming weeks.

The list gives a basic outline of FijiFirst: 60 percent of its candidates — 31 people — have a university bachelor’s degree.

- READ MORE: USP forced to cut costs as Fiji still refuses to pay grant for third year

- Other Fiji elections reports

Very few have anything more, and it would be fair to say, FijiFirst is not rich in intellectuals or academics. No prestigious universities for any of them.

What is important is the fact that just over a third of the candidates — 18 people — have degrees from the Suva-based University of the South Pacific.

They owe their careers and jobs to a university that the FijiFirst government is trying to destroy.

Fiji continues to refuse to pay its USP dues of $88 million — and yet its own candidates benefited from the important regional institution.

The 21 FijiFirst candidates with nothing more than a high school education are famously led by Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama and include his possible successor Inia Seruiratu.

Michael Field is an independent journalist and author and co-editor of The Pacific Newsroom. Republished with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.

-

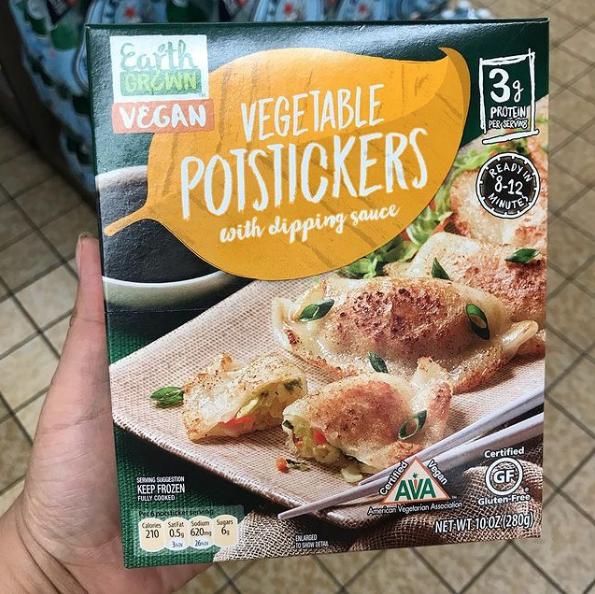

Snacks are truly a godsend—they can get you through a busy work week, a cram session in a dimly lit library basement, and even the kind of colossal breakup that leaves you ugly-crying in that same sad basement searching for something to eat your woes away. To our delight, a number of companies have been making accidentally vegan snacks for years, and we’ve compiled a list of a few of our favorite go-to treats you can find practically anywhere. Bookmark this list for the next time you’re on a road trip in the middle of nowhere, in need of something to munch on at the movies, or trying to get through a difficult moment and are in need of some sweet or salty fuel.

1 Oreo cookies

How could we not include the most iconic cookies to ever exist as the kick-off to this delectable list?

Find it here

2 PringlesThe ultimate stackable snack can be found at your local grocery store—just be sure to go for the vegan-friendly Original flavor (Barbecue is vegan in some regions; check for milk in the ingredients!).

Find it here3 Takis

Two flavors of these spicy, crunchy chips are vegan: Takis Fuego and Takis Nitro.

Find it here4 Unfrosted Pop-Tarts

We already know which vegan flavors we’re having for a mid-morning snack tomorrow: Unfrosted Strawberry, Blueberry, and Brown Sugar.

Find it here

5 Doritos

Finding these Spicy Sweet Chili-flavored tortilla chips at a vending machine or gas station is a safe bet.

Find it here

6 Fritos

The inventor of these salty corn chips was supposedly vegetarian. Try the Original and Bar-B-Q flavors for your dairy-free chip fix.

Find it here

7 Fruit by the FootIntroduced in 1991, the fruity snack is like childhood currency at lunchtime and on playgrounds.

Find it here

8 Ritz Crackers

No butter is added to the original flavor of these buttery, versatile crackers—it’s made with vegetable oils—so enjoy them with vegan cheese, peanut butter, or salsa.

Find it here

9 Sour Patch Kids

We’re ready to get our sweets fix with this chewy, soft, and gelatin-free candy. Even better? Beloved Sour Patch Watermelon is also vegan.

find it here

10 Ruffles Potato Chips

Classic Original and Canadian cult favorite All Dressed are two dairy-free flavors of these recognizable crinkle-cut potato chips.

find it here

11 Smarties

We’re adorning ourselves with Smarties candy necklaces, bracelets, and rings. Nostalgia lane, here we come!

find it here

12 Nature Valley Crunchy Granola Bars

Granola bars are a smart addition when packing your bag for hiking, studying, or traveling. Flavors such as Apple Crisp, Cinnamon, Maple Brown Sugar, Peanut Butter, Pecan Crunch, and Roasted Almond are positively plant-based.

find it here

13 Lay’s Classic Potato Chips

This common party staple’s Classic, Barbecue, Salt & Vinegar, and Lightly Salted Barbecue flavors have no animal-derived ingredients. Sports games and tailgates just got a whole lot simpler.

find it here

14 Smucker’s Uncrustables

You can expect to find these peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in the frozen aisle—the Grape Jelly and Strawberry Jam flavors are vegan. We’re packing them for our next picnic.

find it here

15 Haribo Sour S’ghetti Gummi Candy

It’s sometimes a search to find a gummy candy that has no gelatin, so discovering these gelatin-free sour gummies has us jumping for joy.

find it here

16 Thomas’ New York Style Bagels

If you’re craving a heartier snack, a bagel topped with vegan cream cheese or vegan butter is sure to satisfy. The Blueberry, Cinnamon Swirl, Everything, and Plain versions are plant-based.

Find it here

17 Lindt Dark Chocolate

Dark chocolate in 70, 80, 85, and 90 percent cacao varieties is healthy, right? Right!

find it here

18 Clif Bars

A quintessential snack to take for strenuous outdoor activities, every flavor is vegan except for Mini Blueberry Crisp.

Find it here

19 Nabisco Triscuit Crackers Baked Whole Grain Wheat

We’re seeing a trend—crackers, crackers, and more vegan crackers! We’re diving into Fire Roasted Tomato and Rosemary & Olive Oil Triscuits with hummus and a glass of red wine for a small but titillating treat.

Find it here

20 Nabisco Grahams Original Crackers

Snack-food giant Nabisco is clearly onto something. Its Ginger Snaps, Oreo 100 Calorie Packs, and Saltine Crackers are all also accidentally vegan. Keep ‘em coming!

find it here

21 Snyder’s of Hanover Jalapeño Pretzel Pieces

Jalapeño-flavored anything is sure to have us fired up, but jalapeño-flavored pretzels? Next level. Snyder’s Pretzel Sticks in Oat Bran and Pumpernickel & Onion are also vegan-friendly.

find it here

22 Sun Chips

Often touted as a healthier chip option, it’s no surprise the Original flavor was also vegan all along.

find it here

23 Swedish Fish

Are our eyes deceiving us? Swedish fish?! Yes, please!

find it here

24 Nutter Butter Cookies

Shaped like peanuts with the same creamy, peanut butter taste, and accidentally vegan? We’ll take a case.

find it here

25 belVita Crunchy Breakfast Biscuits

Ideal for someone on the go, these crunchy biscuits provide lasting energy and come in flavors such as Toasted Coconut and Cinnamon Brown Sugar.

find it hereNote: Ingredients may vary by country. This list is only for products sold in the US.

This post was originally published on VegNews.com.

-

If you’re thinking that we’re going to have a beverage today for our backyard National Beer Day festivities, you’d be correct. But what you might not know is that we’re stepping up our brew game by featuring seven plant-based dishes that are made with this frosty drink. Beer has made its way into the food-trend scene, which means everyone can enjoy a frosty libation. From moist stout cupcakes and beer-battered tofu tacos to chocolate stout brownies and beer macaroni and cheese, we’ve compiled a list of the tastiest beer-infused vegan dishes to whet your appetite. So, raise your glass, but don’t take a sip. Instead, enjoy beer cooked into your food. Cheers!

Thyme & Love1 Vegan Beer Brats

With baseball season in swing, beer-infused brats are the perfect addition to any Beer Day celebration. Do like Thyme & Love and cook your favorite Beyond Meat brats in a bath of your go-to summer brew for a flavor you won’t soon forget. Served between soft pretzel buns and loaded with all the fixings, dress up this classic with a side of potato salad (or even baked beans!) for the ultimate meal.

Get the recipe

Vegan Yack Attack2 Thai BBQ Beer Can Cabbage with Daikon Slaw

If you’re the kind of person who likes to experiment with your food, try these inventive sliders from cookbook author (and VegNews contributor) Jackie Sobon. Packed with barbecued beer cabbage (which involves gutting a cabbage, adding beer into it, and slow-grilling the beer-stuffed cabbage until tender and infused with hoppy goodness), the sandwich’s Asian-inspired barbecue sauce and bright daikon slaw make for an incredible handheld.

Get the recipe

Vegan Yack Attack3 Beer & Brat Mac ‘n’ Cheese

Another delicious culinary invention from the kitchen of Jackie Sobon, this Oktoberfest-worthy macaroni and cheese is the ultimate comfort food. The cashew-based sauce is completely swoon-worthy thanks to its luxuriously creamy texture and added oomph from the Golden Ale beer. We’d smother almost anything with it, but Sobon pairs it with perfectly cooked pasta and hearty chunks of vegan seitan bratwurst.

Get the recipe

Minimalist Baker4 Vegan Beer Chili

Is it okay to drink alone if you pour the beer into a pot of chili? We say yes, which is why Minimalist Baker’s one-bowl wonder is our staple for nights spent curled up on the couch. Although the recipe serves eight, we find it’s best suited for the single lifestyle. Simple ingredients? Check. Easy prep? Yep (less than an hour). Freezer-friendly? You bet! Plus, the beer gives it a robust flavor, and the beans give this soup substance. Serve it in a pint glass for a festive touch and enjoy your party of one.

Get the recipe

Hot for Food5 Vegan Beer & Cheddar Bread Bowl Dip

Beer and cheese is the harmonious adult equivalent to peanut butter and jelly, which might explain why Hot for Food created the ultimate gooey, cheesy, plant-based dip perfect for a movie night in (Seaspiracy, anyone?). The dip relies on potatoes and cashews for its classically thick consistency, while the beer, spices, and pickled jalapeños enhance its bold, complex flavor. The dip is poured into a bread bowl and topped with vegan cheddar, green onion, and coconut bacon, so forgo the accouterments and start ripping this bowl apart.

Get the recipe

Healthy Happy Life6 Crispy Beer-Battered Tofu Tacos

Those who say they don’t like tofu obviously have never had Kathy Patalsky’s beer-battered creation. The blogger transforms these bland bricks of soy into crave-able, beer-soaked bites that are simple yet satisfying when paired with pickled onions, cabbage, avocado, vegan chipotle mayonnaise, and hot sauce. The tofu is crispy on the outside, tender on the inside, and tastes delicious inside a warm tortilla. We’re making extra to add to our salads, sandwiches, and Buddha bowls.

Get the recipe

Chocolate Covered Katie7Chocolate Stout Brownies

Stout is an acquired taste, but everyone can learn to love its chocolate accents, thanks to these decadent vegan brownies. Concocted by healthy vegan dessert blog Chocolate Covered Katie, these guiltless brownies are fudgy, stuffed with chocolate chips, and are a surefire pleaser. Note: Katie highly recommends you let these sit overnight in the refrigerator before serving, so plan ahead and make these the night before. We won’t judge if you celebrate a day early by eating the batter.

Get the recipeFor more about beer, read:

The Guide to Vegan Beer

New Vegan Mushroom Fining Technology Could Eliminate Animal Products From Beer

Vegan Beer-Battered Banana Blossom Fish FiletsPhoto credit: Kathy Patalsky

This post was originally published on VegNews.com.

-

Already a one-stop shop for consumers, Target is quickly becoming a vegan haven thanks to a surprising number of cruelty-free products. In fact, the freezer section proudly displays a “Plant-Based Protein” sign above a case packed with brands such as Gardein, Beyond Meat, and Sweet Earth Foods. This budget-friendly store makes vegan living simple with its frequent sales and abundance of options, further proving veganism’s place in the mainstream. So, grab your red shopping cart (and this list!) to make sure you don’t miss any amazing vegan finds at Target.

1Favorite Day Ice Cream Bars

This Target brand line carries many dairy-free options. Look out for these salted caramel and macadamia nut bars and the peanut butter variety.

@knoxvillvevegangrocery/Instagram

@knoxvillvevegangrocery/Instagram2Swiss Miss Vegan Hot Cocoa Mix

Yup! This cult favorite, nostalgic brand has a non-dairy variety. This simple cocoa mix is perfect for whipping up a mug of good old childhood memories. Top with mini vegan marshmallows for the complete experience.

3 Tattooed Chef Foods Meals

Scan the freezer section at your local Target for a plethora of vegan frozen meals from this brand. A few of our favorites? This egg roll bowl, the Spicy Thai bowl, Veggie Hemp Bowl, and the lines frozen pizzas.

@marincountyvegan/Instagram

@marincountyvegan/Instagram4 MyMochi Vegan Bites

Continuing our vegan tour of the freezer section at Target, these frozen, non-dairy mochi bites (in strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate flavors) are must buys.

5 Good & Gather Non-Dairy Butter

Stock up on all those vegan baking basics from butter to whipped cream at Target. Even better? This Target brand is super budget friendly.

6 Place-and-Bake Sweet Lorens Cookie Dough

When a craving for fresh baked cookies hits, these place-and-bake sugar and fudgy brownie cookie dough chunks are great to have on hand. Stash a few in your fridge for emergency cookie cravings.

7 Good & Gather Non-Dairy Cashew-Based Dips

This cashew-based dip from Target’s housebrand captures all the flavors of the cult favorite everything but the bagel seasoning. Keep your eyes peeled for the pizza variety of this dip.

@veganjunkfoodz/Instagram

@veganjunkfoodz/Instagram8 Partake Foods Vegan Cookies