The Federal Reserve’s decision Wednesday to hike interest rates by 75 basis points — the largest increase since 1994 — heightened fears among economists that the central bank’s attempt to tame inflation risks plunging the U.S. economy into recession and inflicting more pain on vulnerable workers.

The Fed’s move came on the heels of worse-than-expected federal data showing that inflation jumped 8.6% in May compared to a year earlier, prompting central bank officials to pursue more aggressive federal-funds rate increases, the Fed’s blunt tool to rein in consumer prices.

But progressive economists have argued for months that interest rate hikes — which are aimed primarily at slowing demand — are the wrong medicine for inflation driven in large part by skyrocketing gas prices and supply-chain disruptions caused by the pandemic.

“Relying on the Fed to bring down prices is like treating someone’s fever by putting them in a freezer,” argued Robert Reich, the former head of the U.S. Department of Labor. “It doesn’t treat the underlying disease, and could make things far worse.”

With the Fed expected to continue pushing up rates at a similar pace in the coming months, analysts are growing increasingly concerned that the central bank will induce an economic slowdown and throw millions out of work in its bid to tackle inflation — a potential echo of the infamous Volcker shock of the 1980s.

“As is well understood, much of the inflation we now see stems from factors that have little to do with the strength of the U.S. economy,” said Dean Baker, senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “The soaring price of oil is due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions. Fed rate hikes will not bring down the price of gas.”

Jerome Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve, admitted as much during a press conference following the Federal Open Market Committee’s closed-door meeting on Wednesday.

“Lots of countries are looking at inflation of 10%, and it’s largely due to commodities prices,” said Powell, a Trump appointee renominated by President Joe Biden in November. “Gas prices — you know, all-time highs and things like that. That’s not something we can do something about.”

Powell told reporters that while the Fed is not actively trying to cause a recession in a bid to bring down prices, “there’s always a risk of going too far” with rate hikes. Powell also acknowledged that “wages are not principally responsible for the inflation that we’re seeing,” though just last month he said the central bank’s goal is to “get wages down” even amid evidence that workers’ share of income is declining.

In a blog post on Wednesday, Reich stressed that “wages are lagging behind inflation.”

“A more accurate description of what we’re now seeing might be called ‘profit-price inflation’ — prices driven upward by corporations seeking increased profits,” Reich argued, pointing to a recent analysis by the Economic Policy Institute showing that record-shattering corporate profits have been contributing disproportionately to inflation.

“I understand the Fed’s urgency, but it has entered dangerous territory,” Reich wrote. “If the Fed continues down this path — as it has signaled it will — the economy will be plunged into a recession. Every time over the last half-century the Fed has raised interest rates this much and this quickly, it has caused a recession.”

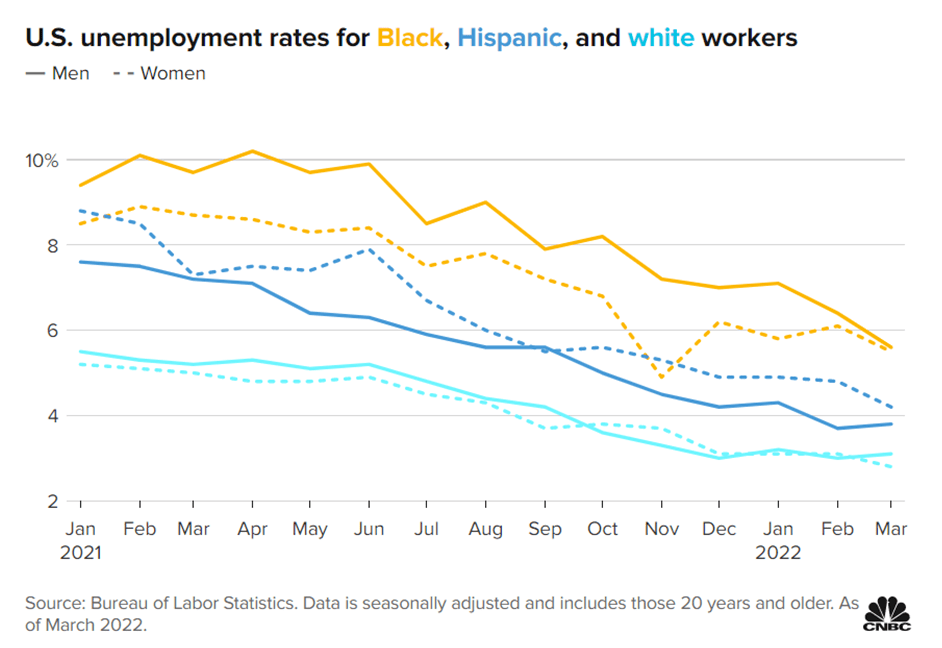

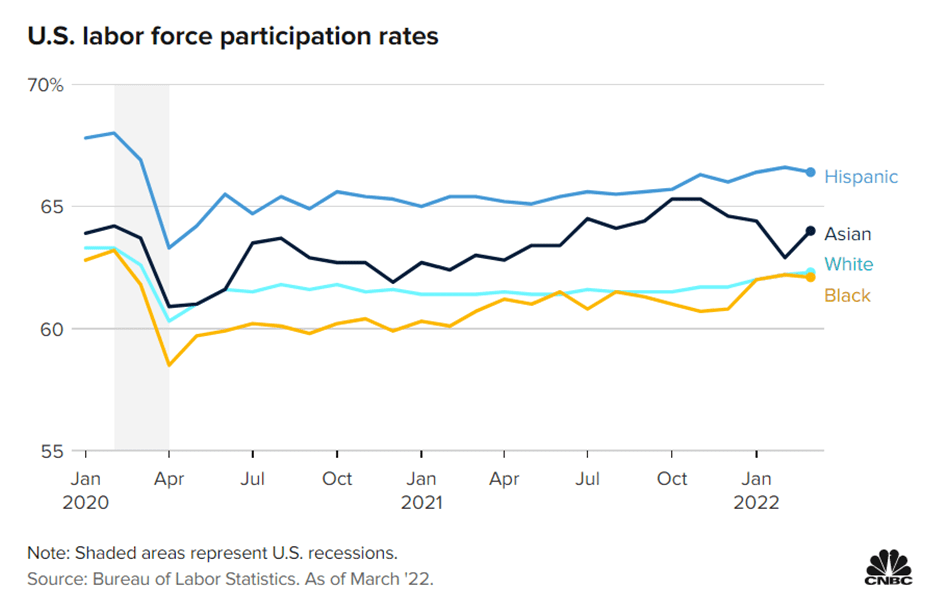

“A recession will be especially harmful to people who are most vulnerable to downturns in the economy — who are the first to be fired (and last to be hired again when the economy turns upward): lower-wage workers, disproportionately women and people of color,” he added. “The Fed is making a big mistake.”

Baker, for his part, noted that Powell is the “first chair in recent decades to explicitly recognize the full employment side of the Fed’s dual mandate and note the huge benefits of low unemployment to Black and Hispanic workers, people with criminal records, and other groups disadvantaged in the labor market.”

“In keeping with this recognition,” Baker said, “the Fed would be well-advised to resist the frenzy of inflation fighters who want to see a whole series of large rate hikes.”

Rampant inflation, a problem that is hardly unique to the U.S., has become a significant economic and political issue for the Biden administration, particularly as the pivotal midterm elections approach.

In an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal late last month, Biden declined to criticize the Fed’s approach to combating inflation, writing that he has “appointed highly qualified people from both parties to lead that institution.”

“The Federal Reserve has a primary responsibility to control inflation,” the president wrote. “My predecessor demeaned the Fed, and past presidents have sought to influence its decisions inappropriately during periods of elevated inflation. I won’t do this … I agree with their assessment that fighting inflation is our top economic challenge right now.”

Biden proceeded to voice support for legislative action to drive down housing and prescription drug costs, Democratic priorities that are stalled in the Senate due largely to Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.). On Tuesday, the president sent a letter to the top executives of major U.S. oil and gas companies imploring them to ramp up production to reduce prices.

But recent survey data indicates that voters overwhelmingly want the president to more forcefully crack down on price-gouging corporations as a way to bring down costs at gas pumps, grocery stores, pharmacies, and elsewhere across the economy. Voters also support a windfall tax on oil and gas giants that are exploiting Russia’s war on Ukraine to rake in huge profits.

“Ahead of the midterms, voters across the nation are eager to support candidates who embrace economic populism and prove to the American people that corporations are no longer above the law,” said Helen Brosnan, executive director of Fight Corporate Monopolies.

This post was originally published on Latest – Truthout.