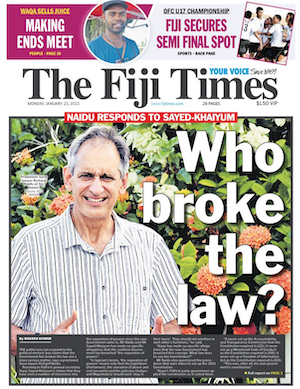

COMMENTARY: By Richard Naidu in Suva

Five weeks on from Christmas Eve, I think most of us are still a bit stunned at what has happened in Fiji.

A new government came to power in dramatic circumstances.

It took not one but two Sodelpa management board meetings to change it, with razor-thin margins.

The same drama extended into Parliament.

There was definitely a bump in the road when the military openly expressed concern about the speed of change.

But that was navigated smoothly.

One other thing stood on a razor-thin margin.

Nobody in Fiji should forget it.

‘Rule of law’

A little thing called “rule of law”.

In a Fiji Times column last week, I tried to capture the idea of this.

First, the idea that the law is more important than everyone, including the government.

But second, the idea that the law is more than just rules and regulations which restrict us.

Rule of law means also that the government is bound to respect ordinary people’s rights and freedoms.

That rule of law was seriously at risk under the FijiFirst government.

Things had gotten to the point where, using bullying and fear, unafraid of the courts or any other institution which might restrain it, the FijiFirst government just did what it wanted.

In its last year of power, the only restraint on FijiFirst was the fact that an election was coming.

Turned on opponents

Had it won that election, FijiFirst would have turned its guns on the only opponents it had left — the opposition political parties, the independent news media and the few non-government organisations that continued to criticise it.

Fiji would have fallen firmly into that growing group of countries now called “democratic dictatorships” — places which have elections and the other trappings of democracy, but which in truth severely restrict the democratic rights and freedoms of their people.

Four key officials holding important constitutional positions — the Chief Justice, the Commissioner of Police, the Commissioner of Corrections and the Supervisor of Elections — have been suspended inside of four weeks.

That tells us one of two things.

Either the new government is particularly vengeful.

Or there are complaints against these officials that date back to the FijiFirst party’s time in power and which are only now coming to light.

After all, they’ve hardly had time to offend us under the new government.

And if these are in fact complaints about things which happened long ago, we must ask — why were they not actioned under the FijiFirst government?

No one dared complain

Or was fear of the government so pervasive that no one dared to complain against these officials — and the complaints are only being made now?

We need to know about these complaints.

Yes, each of these officials is innocent until proven otherwise.

But they are public officials, occupying some of the most powerful and critical positions in the country.

The decisions they make concern our most basic rights and freedoms — whether or not we spend a night in a cell, whether (and when) we will get a ruling on our employment dispute, or whether we are able to vote.

So we, the public, have a right to know what they are accused of.

What has changed?

The overwhelming sentiment for most of us — at least those around me — is a new sense of freedom.

Doesn’t change things

For many of us, that does not really change things from day to day.

Not everyone has the compelling urge to air their opinions on everything (in newspaper columns or elsewhere).

But it is simply the fact that if you want to rant about something on Facebook, you’re not worrying about what the government will think.

Most of us, day to day, are not worrying about whether we will be unfairly held for 48 hours in a jail cell.

Yet only two years ago in the covid crisis, the police were doing that to hundreds of people.

We are not worrying about whether we will be arrested for saying something which will “cause public alarm”.

Yet, every time an NGO or opposition political party leader issued a public statement in the last 10 years, this was a constant worry.

But much of the real damage done was at the next level down — the level where ordinary people like us want to get things done.

This week I met a small group of distinguished doctors.

Climate of fear

I heard with some amazement about the climate of fear which predominated in the Ministry of Health.

Criticism was not permitted.

In November last year, the permanent Secretary for Health publicly told politicians to “leave the Health Ministry alone”.

Nobody, he said, should talk about it.

Nobody should “undermine” it — because it was on the cusp of great things.

One senior medical specialist who famously criticised the state of our hospitals in The Fiji Times was immediately banned from entering them.

This was hardly a hardship — he was only volunteering his skills for free.

But what about all the patients who he was looking after?

He recounted to me, with some wonder the bureaucratic memo-writing process that is now being followed to bring him back.

Cash and volunteers

The International Women’s Association has cash and volunteers ready to improve women’s and children’s health at CWM Hospital.

We are talking about basic things, like hot water and decrepit bathrooms.

How do you run hospital wards without hot water?

IWA’s mistake was to make these deficiencies public on social media.

So the Health Ministry stopped talking to IWA.

Only with the change of government is IWA allowed to openly communicate with the Ministry of Health about what it wants to do — instead of whispers to officials on their gmail accounts.

For years, I have marvelled at the stupidity of the edicts issued from Ministry of Education headquarters.

Schools may not fund-raise without permission.

Schools may not invite speakers to their school assemblies without permission.

Schools may not run extracurricular classes for students without their permission.

‘In name of equality’

The policy seems to be “in the name of equality, we must all be equally dumbed down”.

As the Education Ministry pursued the government’s mad obsession with our “secular state”, schools owned by religious bodies cannot choose their own school heads, even if they pay for them and save the government money.

Education and health are critical issues for all of us.

The government can’t deliver everything.

Governments by nature are unwieldy, bureaucratic and slow (sometimes for good reason, because they have to carefully manage public funds and follow other laws).

So people have to get involved.

Get involved

We also have to get involved on a wide swathe of other issues such as poverty, domestic violence, drug abuse, crime and economic opportunities.

Criticism not welcome

These are all things which, for the past 15 years, we were told, the government had under control — like “never before”.

Our input — and certainly our criticism — were not welcome.

Let’s be clear about our new government.

We might be glad that it’s there.

And we should never take for granted the rights and freedoms it has restored to us and the refreshing new attitude it brings after 15 years.

But soon the honeymoon will end, the shine will come off and we will all have to get down to the work (which never ends) of solving our deep social and economic problems.

The expectations on the new government are huge.

Everybody wants every problem to be solved and every complaint to be answered.

We want every crook who has received an unfair benefit to be (as we now always seem to say) “taken to task”.

Same huge debt

The new government has the same huge debt, the same shortage of cash and the same lack of resources the old government did.

It can move some money around and change some priorities — but it can never solve every problem.

But a government that is prepared to tolerate criticism has at least one advantage over one that is not.

It can hear from real people about where the real problems are.

That’s why freedom of expression is not just a nice thing to have.

It’s actually important to tell us what is going on.

This government, like the old one, will gradually become more complacent and unresponsive as it becomes burdened with the ordinary business of administration.

And that is why every democracy — at least every real one — prizes freedom.

Freedom to march

Freedom for people to criticise, to march in the street, to take the government to court, without being punished for it.

These are some of the tools we use to hold the government to account, to remind the politicians that it is about us, not them, and to embarrass the politicians into action.

But just as important is the responsibility on us not just to talk — but also to act.

Our new freedom also means freedom to get involved.

What are the things that are important to us?

Is it health?

Education?

Child poverty?

Prison reform?

Our local environment?

So what will we do?

Don’t take it for granted

We don’t need to be part of some official committee or NGO to fight for the things that are important to us.

We don’t need the government’s permission to hold a public forum to talk about problems and solutions.

After 15 years we need to be able to say to our leaders: “We’re in charge here. This is what we want. You work for us.”

They won’t always listen — but that’s what freedom is.

It was a close-run thing on Christmas Eve — but freedom is what we got.

So let’s not take it for granted.

Let’s use it.

Richard Naidu is a Suva lawyer who is fairly free with his opinions. The views in this article are not necessarily the views of The Fiji Times. Republished with permission.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.